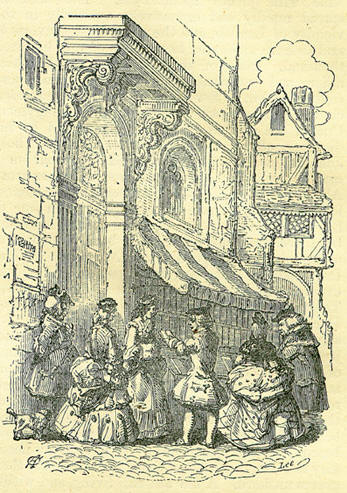

27th DecemberBorn: Jacques Bernouilli, mathematician, 1654, Basle; Dr. Conyers Middleton, philosophical and controversial writer, 1683, Hinderwell, near Whitby; Pope Pius VI, 1717; Arthur Murphy, dramatist and miscellaneous writer, 1727, Ireland. Died: Pierre de Ronsard, poet, 1585, St. Cosme Priory, near Tours; Thomas Cartwright, Puritan divine, 1603; Captain John Davis, navigator, killed near Malacca, 1605; Thomas Guy, founder of Guy's Hospital, 1724, London; Henry Home, Lord Kames, lawyer and metaphysician, 1782; Prince Lee Boo, of Pelew, 1784, London; John Wilkes, celebrated demagogue, 1797; Dr. Hugh Blair, eminent divine, 1800, Edinburgh,; Joanna Southcott, female enthusiast and prophet, 1814, London; Charles Lamb, poet and essayist, 1834, Edmonton; Rev. William Jay, eminent dissenting preacher, 1853, Bath,; Josiah Conder, editor and miscellaneous writer, 1855. Feast Day: St. John, apostle and evangelist. St. Theodorus Grapt, confessor, 9th century. ST. JOHN THE EVANGELIST'S DAYA special reverence and interest is attached to St. John-'the disciple whom Jesus loved.' Through a misapprehension of the Saviour's words, a belief, we are informed, came to he entertained among the other apostles that this disciple should never die, and the notion was doubtless fostered by the circumstance, that John outlived all his brethren and coadjutors in the Christian ministry, and was indeed the only apostle who died' a natural death. He expired peacefully at Ephesus, it is stated, at the advanced age of ninety-four, in the reign of the Emperor Trajan, and the year of our Lord 100; thus, as Brady observes, 'making the first century of the Christian Era and the Apostolical Age, terminate together.' Though John thus escaped actual martyrdom, he was, nevertheless, called upon to endure great persecution in the cause of his Friend and Master. Various fathers of the church, among others Tertullian and St. Jerome, relate that in the reign of Domitian, the Evangelist, having been accused of attempting to subvert the religion of the Roman Empire, was transported from Asia to Rome, and there, in presence of the emperor and senate, before the gate called Porta Latina, or the Latin Gate, he was cast into a caldron of boiling oil, which he not only remained in for a long time uninjured, but ultimately emerged from, with renovated health and vigor. In commemoration of this event, the Roman Catholic Church retains in its calendar, on the 6th of May, a festival entitled 'St. John before the Latin Gate.' Domitian, we are further informed, notwithstanding this miraculous interposition, continued obdurate, and banished St. John to Patmos, a lonely island in the Grecian Archipelago, where he was employed in working among the criminals in the mines. In this dreary abode, the apostle, as he informs us himself, witnessed those sublime and wondrous visions, which he has recorded King the Apocalypse. On the assassination of Domitian, and the elevation of Nerva to the imperial throne, John was released from his confinement at Patmos, and returned to Ephesus, where he continued till his death. A tradition obtains, that in his last days, when unable to walk to church, he used to be carried thither, and exhorted the congregation in his own memorable words, 'Little children, love one another.' Partly in reference to the angelic and amiable disposition of St. John, partly also, apparently, in allusion to the circumstance of his having been the youngest of the apostles, this evangelist is always represented as a young man, with a heavenly mien and beautiful features. He is very generally represented holding in his left hand an urn, from which a demoniacal figure is escaping. This device appears to bear reference to a legend which states that, a priest of Diana having denied the divine origin of the apostolic miracles, and challenged St. John to drink a cup of poison which he had prepared, the Evangelist, to remove his skepticism, after having first made on the vessel the sign of the cross, emptied it to the last drop without receiving the least injury. The purging of the cup from all evil is typified in the flight from it of Satan, the father of mischief; as represented in the medieval emblem. From this legend, a superstitious custom seems to have sprung of obtaining, on St. John's Day, supplies of hallowed wine, which was both drunk and used in the manufacture of manchets or little loaves; the individuals who partook of which were deemed secure from all danger of poison throughout the ensuing year. The subjoined allusion to the practice occurs in Googe's translation of Naogeorgus: Nexte John the sonne of Zebedee hath his appoynted day, Who once by cruell Tyrannts' will, constrayned was they say Strong poyson up to drinke; therefore the Papistes doe beleeve That whoso puts their trust in him, no poyson them can greeve: The wine beside that halowed is in worship of his name, The Priestes doe give the people that bring money for the same. And after with, the selfe same wine are little manchets made Agaynst the boystrous Winter stormes, and sundrie such like trade. The men upon this solemne day, do take this holy wine To make them strong, so do the maydes to make them faire and fine. THOMAS GUY, AND GUY'S HOSPITAL: 'BOOKSELLERS AND STATIONERS'There is one noble institution in the metropolis, Guy's Hospital, which renders a vast amount of good to the poor, without any appeal either to the national purse or to private benevolence. Or, more correctly, this is a type of many such institutions, thanks to the beneficence of certain donors. Once now and then, it is necessary to bring public opinion to bear upon these charities, to insure equitable management; but the charities themselves are noble. Thomas Guy was the son of a coal-merchant and lighterman, at Horseleydown, and was born in 1645. He did not follow his father's trade, but was apprenticed to a bookseller, and became in time a freeman and liveryman of the Stationers' Company. He began business on his own account as a book-seller, in a shop at the corner of Cornhill and Lombard Street, pulled down some years ago when improvements were made in that neighbourhood. He made large profits, first by selling Bibles printed in Holland, and then as a contractor for printing Bibles for Oxford University. He next made much money in a way that may, at the present time, seem beneath the dignity of a city shopkeeper, but which in those days was deemed a matter of course: viz., by purchasing seamen's tickets. The government, instead of paying seamen their wages in cash, paid them in bills or tickets due at a certain subsequent date; and as the men were too poor or too improvident to keep those documents until the dates named, they sold them at a discount to persons who had ready cash to spare. Mr. Guy was one of those who, in this way, made a profit out of the seamen, owing to a bad system for which the government was responsible. About that time, too, sprung up the notorious scheme called the South-Sea Company, which ultimately brought ruin and disgrace to many who had founded or fostered it. Guy did not entangle himself in the roguery of the company; but he bought shares when low, and had the prudence to sell out when they were high. By these various means he accumulated a very large fortune. Pennant deals with him rather severely (in his History of London) for the mode in which a great part of his fortune was made; but, taking into consideration the times in which he lived, his proceedings do not seem to call for much censure. When his fortune was made, he certainly did good with it. He granted annuities to many persons in impoverished circumstances he made liberal benefactions to St. Thomas's Hospital; he founded an almshouse at Tamworth, his mother's native town; he left a perpetual annuity of £400 to Christ's Hospital, to receive four children yearly nominated by his trustees and he gave large sums for the discharge of poor debtors. The following anecdote of him may here be introduced: '[Guy] was a man of very humble appearance, and of a melancholy cast of countenance. One day, while pensively leaning over one of the bridges, he attracted the attention and commiseration of a bystander, who, apprehensive that he meditated self-destruction, could not refrain from addressing him with an earnest entreaty 'not to let his misfortunes tempt him to commit any rash act;' then, placing in his hand a guinea, with the delicacy of genuine benevolence, he hastily with-drew. Guy, roused from his reverie, followed the stranger, and warmly expressed his gratitude; but assured him he was mistaken in supposing him to be either in distress of mind or of circumstances making an earnest request to be favoured with the name of the good man, his intended benefactor. The address was given, and they parted. Some years after, Guy, observing the name of his friend in the bankrupt-list, hastened to his house; brought to his recollection their former interview; found, upon investigation, that no blame could be attached to him under his misfortunes; intimated his ability and full intention to serve him; entered into immediate arrangements with his creditors; and finally re-established him in a business which ever after prospered in his hands, and in the hands of his children's children, for many years, in Newgate Street.' The great work for which Thomas Guy is remembered, is the hospital bearing his name, in the borough. In connection with the foundation of this building, a curious anecdote has been related, which, though now somewhat hackneyed, will still bear repetition. Guy had a maid-servant of strictly frugal habits, and who made his wishes her most careful study. So attentive was she to his orders on all occasions, that he resolved to make her his wife, and he accordingly informed her of his intention. The necessary preparations were made for the wedding; and among others many little repairs were ordered, by Mr. Guy, in and about his house. The latter included the laying down a new pavement opposite the street-door. It so happened that Sally, the bride-elect, observed a portion of the pavement, beyond the boundary of her master's house, which appeared to her to require mending, and of her own accord she gave orders to the workmen to have this job accomplished. Her directions were duly attended to in the absence of Mr. Guy, who, on his return, perceived that the workmen had carried their labours beyond the limits which he had assigned. On inquiring the reason, he was informed that what had been done was by the mistress's orders.' Guy called the foolish Sally, and telling her that she had forgotten her position, added: 'If you take upon yourself to order matters contrary to my instructions before we are married, what will you not do after? I therefore renounce my matrimonial intentions towards you.' Poor Sally, by thus assuming an authority to which she then had no claim, lost a rich husband, and the country gained the noble hospital; named after its founder, who built and endowed it at a cost of £238,292. Guy was seventy-six years of age when he matured the plan for founding an hospital. He procured a large piece of ground on a lease of 999 years, at a rent of £30 per annum, and pulled down a number of poor dwellings which occupied the site. He laid the first stone of his new hospital in 1722, but did not live to witness the completion of the work; for he died on the 27th of December 1724--just ten days before the admission of the first sixty patients. His trustees procured an act of parliament for carrying out the provisions of his bequest. They leased more ground, and enlarged the area of the hospital to nearly six acres; while the endowment or maintenance fund was laid out in the purchase of estates in Essex, Herefordshire, and Lincolnshire. The building itself is large and convenient, but not striking as an architectural pile. This has indeed been a lucky hospital; for, nearly a century after Guy's death, an enormous bequest of nearly £200,000 was added to its funds. Mr. Hunt, in 1829, left this sum, expressly to enlarge the hospital to the extent of one hundred additional beds. The rental of the hospital estates now exceeds £30,000 per annum. In the open quadrangle of the hospital is a bronze statue of Guy by Scheemakers; and in the chapel, a marble statue of him by Bacon.  ln connection with Thomas Guy, who, of all the members of the Stationers' Company of London, may certainly he pronounced to have been one of the most successful in the acquisition of wealth, an interesting circumstance regarding the original import of the term stationer calls here for notice. Up to about the commencement of the last century, the term in question served almost exclusively to denote a bookseller, or one who had a station or stall in some public place for the sale of hooks. An instance of this application of it occurs in the following passage in Fuller's Worthies of England: 'I will not add that I have passed my promise (and that is an honest man's bond) to my former stationer, that I will write nothing for the future, which was in my former hooks so considerable as may make them interfere one with another to his prejudice.' The annexed engraving exhibits a stationer's stall or bookseller's shop in ancient times, when books were generally exposed for sale in some public place in the manner here represented. A parallel to this mode of conducting business still exists in the book-fairs at Leipsic and Frankfort, in Germany. In medieval days, the stationarius or stationer was an official connected with a university, who sold at his stall or station the books written or copied by the libraries or book-writer. From this origin is derived the modern term stationer, which now serves exclusively to denote an individual whose occupation consists in supplying the implements instead of the productions of literary labour. JOANNA SOUTHCOTTJoanna Southcott was born about the year 1750, of parents in very humble life. When about forty years old, she assumed the pretensions of a prophetess, and declared herself to be the woman mentioned in the twelfth chapter of the Book of Revelation. She asserted that, having received a divine appointment to be the mother of the Messiah, the visions revealed to St. John would speedily be fulfilled by her agency and that of the son, who was to be miraculously born of her. Although extremely illiterate, she scribbled much mystic and unintelligible nonsense as visions and prophecy, and for a time carried on a lucrative trade in the sale of seals, which were, under certain conditions, to secure the salvation of the purchasers. The imposture was strengthened by her becoming subject to a rather rare disorder, which gave her the appearance of pregnancy after she had passed her grand climacteric. The faith of her followers now rose to enthusiasm. They purchased, at a fashion-able upholsterer's, a cradle of most expensive materials, and highly decorated, and made costly preparations to hail the birth of the miraculous babe with joyous acclamation. The delusion spread rapidly and extensively, especially in the vicinity of London, and the number of converts is said to have amounted to upwards of one hundred thousand. Most of them were of the humbler order, and remarkable for their ignorance and credulity; but a few were of the more educated classes, among whom were two or three clergymen. One of the clergymen, on being reproved by his diocesan, offered to resign his living if 'the holy Johanna,' as he styled her, failed to appear on a certain day with the expected Messiah in her arms. About the close of 1814, however, the prophetess herself began to have misgivings, and in one of her lucid intervals, she declared that 'if she had been deceived, she had herself been the sport of some spirit either good or evil.' On the 27th of December in that year, death put an end to her expectations-but not to those of her disciples. They would not believe that she was really dead. Her body was kept unburied till the most active signs of decomposition appeared; it was also subjected to a post-mortem examination, and the cause of her peculiar appearance fully accounted for on medical principles. Still, numbers of her followers refused to believe she was dead; others flattered themselves that she would speedily rise again, and bound themselves by a vow not to shave their beards till her resurrection. It is scarcely necessary to state, that most of them have passed to their graves unshorn. A few are still living, and within the last few years several families of her disciples were residing together near Chatham, in Kent, remarkable for the length of their beards, and the general singularity of their manners and appearance. Joanna Southcott was interred, under a fictitious name, in the burial-ground attached to the chapel in St. John's Wood, London. 'A stone has since been erected to her memory, which, after reciting her age and other usual particulars, concludes with some lines, evidently the composition of a still unshaken believer, the fervor of whose faith far exceeds his inspiration as a poet.' CHARLES AND MARY LAMBThe lives of literary men are seldom characterised by much stirring adventure or variety of incident. The interest attaching to them consists mainly of the associations with which they are intertwined-the joys, trials, and sorrows of their domestic history, and the tracing of the gradual development of their genius to its culminating-point, from its first unfledged essays. In contemplating their career, much benefit may he derived both by the philosopher and moralist-the former of whom will gain thereby a deeper and more thorough knowledge of the workings of human nature, and the latter reap many an instructive and improving lesson. Few biographies display so much beauty, or are more marked by a touching and lively interest, than those of Charles Lamb and his sister Mary. Devotedly attached to each other, united together by a strong sympathy both in mental and physical temperament, and a highly-refined and cultivated literary taste, they passed from youth to age; and when first the brother, and afterwards the sister, were laid in the same grave, in the peaceful churchyard of Edmonton, it might truly be said of them, that they 'were lovely and pleasant in their lives, and in their death they were not divided.' We shall now present the reader with a brief sketch of their history. Their father, John Lamb, was a clerk to Mr. Salt, a bencher of the Inner Temple; and in Crown Office how of this classic locality, Charles was born in February 1775. His sister Mary was ten years older than himself, and there was also an elder brother, John. Young Lamb's early associations were thus all of a quaint and antiquarian nature. The grand old Temple church, so impressive, both from its architectural beauty and the romantic interest attached to its former possessors, the Knights Templars', who repose in its precincts; the dim walks and passages of the inns-of-court, redolent alike of learning and jurisprudence; and the pleasant sunny gardens descending to the noble Thames, where King Edward of yore had mustered a gallant array of knighthood and men-at-arms, ere setting forth on his last expedition to Scotland-all combined to stamp their impress on the mind of a sensitive, affectionate, and poetic child. At the age of seven, he obtained a presentation to Christ's Hospital, where the ensuing seven years of his life were spent, and a lasting friendship formed with the poet Coleridge, then a student at the same institution. Lamb made here considerable progress in classical learning; but an impediment of speech, which clung to him through life, prevented him, as originally intended, from entering the church, a profession indeed to which his inclinations were not adapted; and he accordingly quitted school at fourteen, and was placed for a time in the South-sea House, where his brother John held a situation. From this he was, in a year or two, transferred to a clerkship in the East India House, an establishment in which he gradually rose to the enjoyment of a large salary; and was ultimately pensioned off on a handsome allowance, a few years previous to his death. Shortly after entering on this employment, his parents removed from the Temple to Little Queen Street, Holborn. The pecuniary resources of the family were at this time but scanty, consisting of Charles's then small salary from the East India House, an annuity enjoyed by his father from the liberality of his old master, Mr. Salt, and the scanty returns which his sister Mary could procure by her industry with the needle. Old Mr. Lamb was now sinking into dotage, and his wife was stricken by an infirmity which deprived her of the use of her limbs. An old maiden-aunt, whom Charles has affectionately commemorated, resided with them, and paid them a small board. Notwithstanding all the difficulties with which they had to struggle, the affection which bound the different members of the family together, and, more especially, Mary and Charles, secured their enjoyment of a large share of happiness; but a fearful misfortune was about to overtake them. A predisposition to insanity seems to have been inherited by the Lambs. At the age of twenty, Charles was seized by a fit of this malady, which compelled his removal, for a few weeks, to a lunatic asylum. His recovery, however, was complete and final; and till the end of his life his intellect remained sound and unclouded. A sadly different fate was that of poor Mary, his sister. Worn out by her double exertions in sewing and watching over her mother, who required constant attention, her mind which, on previous occasions, had been subject to aberration, gave way, and burst into an ungovernable frenzy. One day after the cloth had been laid for dinner, the malady attacked her with such violence, that, in a transport she snatched up a knife, and plunged it into the breast of her mother, who was seated, an invalid, in a chair. Her father was also present, but unable from frailty to interpose any obstacle to her fury; and she continued to brandish the fatal weapon, with loud shrieks, till her brother Charles entered the room, and took it from her hand. Assistance was procured, and the unfortunate woman was conveyed to a madhouse, where, in the course of a few weeks, she recovered her reason. In the meantime, her mother was dead, slain, though in innocence, by her hand; her father and aunt were helpless; and her brother John disposed to concur with the parish authorities and others in detaining her for life in confinement. In this conjuncture, Charles stepped forward, and by pledging himself to under-take the future care of his sister, succeeded in obtaining her release. Nobly did he fulfill his engagement by the sedulous and unremitting care with which he continued ever afterwards to watch over her, abandoning all hopes of marriage to devote himself to the charge which he had undertaken. It was a charge, indeed, unfrequently onerous, as Miss Lamb's complaint was constantly recurring after intervals, necessitating her removal for a time to an asylum. It was a remarkable circumstance connected with her disease, that she was perfectly conscious of its approach, and would inform her brother, with as much gentleness as possible, of the fact, upon which he would ask leave of absence from the India House, as if for a day's pleasuring, and accompany his sister on her melancholy journey to the place of confinement. On one of these occasions, they were met crossing a meadow near Hoxton by a friend, who stopped to speak to them, and learned from the weeping brother and sister their destination. In setting forth on the excursions which at first they used to make annually, during Lamb's holidays, to some place in the country, Mary would always carefully pack up in her trunk a strait-waistcoat, to be used in the event of one of her attacks coming on. Latterly, these jaunts Earl to lie abandoned, as they were found to exercise on her all injurious influence. The attendance required from Lamb at the India House was from ten to four every day, leaving him in general the free enjoyment of his evenings. These were devoted to literary labours and studies, diversified not unfrequently by social meetings with his friends, of whom his gentle and amiable nature had endeared to him an extensive circle. On Wednesday evenings, he usually held a reception, at which the principal literary celebrities of the day would assemble, play at whist, and discuss all matters of interest relating to literature, the fine arts, and the drama. Among those present on these occasions, in Lamb's younger days, might be seen Godwin, Hunt, and Hazlitt, and when in town, Wordsworth, Southey, and Coleridge. At a later period, Allan Cunningham, Cary, Edward Irving, and Thomas Hood would be found among the guests. Shortly after Miss Lamb's first release from confinement, her brother and she removed from Holborn to Bentonville, where, however, they did not remain long, and in 1800 took up their abode in the Temple, in which locality, dear to the hearts of both of them from early associations, they resided about seventeen years, probably the happiest period of their existence. From the Temple, they removed to Russell Street, Covent Garden, and thence to Colebrook Cottage, Islington, on the banks of the New River, where, rather curious to say, Lamb, for the first time in his life, found himself raised to the dignity of a householder, having hitherto resided always in lodgings. Not long, too, after his settling in this place, he exchanged the daily drudgery of the desk for the independent life of a gentleman at large, having been allowed to retire from the India House on a comfortable pension. In a few years, however, his sister's increasing infirmities, and the more frequent recurrence of her mental disorder, induced him to quit London for the country, and he took up his abode at Enfield, from which he afterwards migrated to Edmonton. Here, in consequence of the effects of a fall, producing erysipelas in the head, he expired tranquilly and without pain, after a few days' illness, in December 1834. His sister was labouring at the time under one of her attacks, and was therefore unable to feel her loss with all the poignancy which she would otherwise have experienced. She survived her brother for upwards of twelve years, and having been latterly induced by Her friends to remove from Enfield to London, died quietly at St. John's Wood on 20th May 1847. It is now proper to refer to Lamb's literary works. Being independent of the pen as a main support, his writings are more in the character of fugitive pieces, contributed to magazines, than of weighty and voluminous lucubration's. As an author, his name will principally be recollected by his celebrated Essays of Elia, originally contributed to the London Magazine, and a second series, even superior to the first, entitled the Last Essays of Ella. These delightful productions, so racy and original, place Lamb incontestably in the first rank of our British essayists, and fairly entitle him to contest the palm with Addison and Steele. Egotistical they may in one sense be termed, as the author's personal feelings and predilections, with many of his peculiar traits of character, are brought prominently forward; but the egotism is of the most charming and unselfish kind-a sentiment which commends itself all the more winningly to us when he conies to speak of his sister under the appellation of his Cousin Bridget. Other essays and pieces were contributed by him to various periodicals, including Leigh Hunt's Reflector, Blackwood's Magazine, and the Englishman's Magazine, and bear all the same character of quaintness, simplicity, and playful wit. In his early days, his tendencies had been principally exerted in the direction of poetry, in the production of which there was a sort of co-partnership betwixt him and Coleridge, along with Charles Lloyd, and a volume of pieces by the trio was published at Bristol in 1797. As a votary of the Muses, however, Lamb's claims cannot be highly rated, his poems, though graceful and melodious, being deficient both in vigour and originality of thought. The one dramatic piece, the Farce of Mr. IT, which he succeeded in getting presented on the boards of Drury Lane, was shelved on the first night of its representation. The disappointment was borne manfully by him, and as he sat with his sister in the pit, Lamb joined himself in the hisses by which the fate of his unfortunate bantling was sealed. Allusion has already been made to Lamb's amiability of disposition. Through the whole course of his life he never made a single enemy, and the relations between him and his friends were scarcely ever disturbed by the slightest fracas. To use a favourite expression of Lord Jeffrey, 'he was eminently sweet-blooded.' Though of a highly poetic and imaginative temperament, Lamb took little pleasure in rural scenery. A true child of London, no landscape, in his estimation, was comparable with the crowded and bustling streets of the great metropolis, Covent-Garden Market and its piazzas, or the gardens of the inns of court. A visit to Drury Lane or Covent-Garden Theatre in the evening, a rubber at whist, or a quiet fireside-chat with a few friends, not unaccompanied by the material consolations of sundry steaming beverages and the fragrant fumes of the Virginian weed, were among his dearest delights. One unfortunate failing must here be recorded-his tendency, on convivial occasions, to exceed the limits of temperance. This, however, can scarcely be regarded as a habitual error on his part, and has probably received a greater prominence than it merited, from his well-known paper, The Confessions of a Drunkard, in which he has so graphically described the miserable results of excess. Another predilection, his addiction to the use of tobacco, was ultimately overcome by him after many struggles. His tastes, in the consumption of the fragrant weed, were not very delicate, inducing him to use the strongest and coarsest kinds. On being asked one day by a friend, as he was puffing forth huge volumes of smoke, how he had ever managed to acquire such a practice, he replied: 'By striving after it as other men strive after virtue. His convivial habits leading him not unfrequently to 'hear the chimes at midnight,' his appearance at business next morning was some-times considerably beyond the proper hour. On being one day reproved by his superior for his remissness in this respect, the answer was: 'True, sir, very true, I often conic late, but then, you know, I always go away early.' To a man of his disposition, it can be readily supposed that the dull routine of his duties at the India House was a most distasteful drudgery, and we accordingly find him often bewailing humorously his lot in letters to his correspondents. His good sense, however, rendered him perfectly aware of the benefits of regular employment and a fixed income, and his complaints must therefore be regarded in a great measure as ironical, the offspring of the spirit of grumbling, so characteristic of the family of John Bull. During the intervals of her malady, Miss Lamb appeared in her natural and attractive aspect, the well-bred mistress of her brother's house, doing its honours with all grace, and most tenderly solicitous and careful in everything relating to his comfort. Her conversation and correspondence were both lively and genial, and possessing the same literary tastes as Charles, she was often associated with him in the production of various works. These were chiefly of a juvenile nature, including the charming collection of Tales from Shakespeare; Mrs. Leicester's School; and Poetry for Children. |