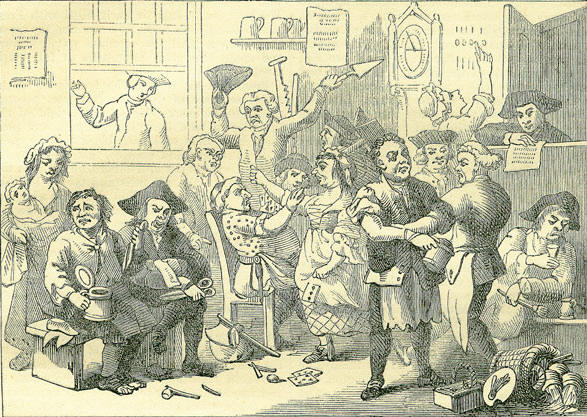

26th DecemberBorn: Gulielmus Xylander, translator of the classics, 1532, Augsburg; Thomas Gray, poet, 1716, Cornhill, London. Died: Antoine Houdart de in Motte, dramatist, 1731, Paris; Joel Barlow, American author and diplomatist, 1812, near Cracow; Stephen Girard, millionaire, 1831. Feast Day: St. Stephen, the first martyr. St. Dionysius, pope and confessor, 269. St. Iarlath, confessor, first bishop of Team, in Ireland, 6th century. St. Stephen's DayTo St. Stephen, the Proto-martyr, as he is generally styled, the honour has been accorded by the church of being placed in her calendar immediately after Christmas-day, in recognition of his having been the first to seal with his blood the testimony of fidelity to his Lord and Master. The year in which he was stoned to death, as recorded in the Acts of the Apostles, is supposed to have been 33 A.D. The festival commemorative of him has been retained in the Anglican calendar. A curious superstition was formerly prevalent regarding St. Stephen's Day-that horses should then, after being first well galloped, be copiously let blood, to insure them against disease in the course of the following year. In Barnaby Googe's translation of Naogeorgus, the following lines occur relative to this popular notion: Then followeth Saint Stephen's Day, whereon doth every man His horses jaunt and course abrode, as swiftly as he can, Until they doe extremely sweate, and then they let them blood, For this being done upon this day, they say doth do them good, And keepes them from all maladies and sicknesse through the yeare, As if that Steven any time tooke charge of horses heare. The origin of this practice is difficult to be accounted for, but it appears to be very ancient, and Douce supposes that it was introduced into this country by the Danes. In one of the manuscripts of that interesting chronicler, John Aubrey, who lived in the latter half of the seventeenth century, occurs the following record: On St. Stephen's Day, the farrier came constantly and blouded all our cart-horses.' Very possibly convenience and expediency combined on the occasion with superstition, for in Tusser Redivivus, a work published in the middle of the last century, we find this statement: 'About Christmas is a very proper time to bleed horses in, for then they are commonly at house, then spring comes on, the sun being now coming back from the winter-solstice, and there are three or four days of rest, and if it be upon St. Stephen's Day it is not the worse, seeing there are with it three days of rest, or at least two.' In the parish of Drayton Beauchamp, Bucks, there existed long an ancient custom, called Stephening, from the day on which it took place. On St. Stephen's Day, all the inhabitants used to pay a visit to the rectory, and practically assert their right to partake of as much bread and cheese and ale as they chose at the rector's expense. On one of these occasions, according to local tradition, the then rector, being a penurious old bachelor, determined to put a stop, if possible, to this rather expensive and unceremonious visit from his parishioners. Accordingly, when St. Stephen's Day arrived, he ordered his housekeeper not to open the window-shutters, or unlock the doors of the house, and to remain perfectly silent and motionless whenever any person was heard approaching. At the usual time the parishioners began to cluster about the house. They knocked first at one door, then at the other, then tried to open them, and on finding them fastened, they called aloud for admittance. No voice replied. No movement was heard within. 'Surely the rector and his house-keeper must both be dead!' exclaimed several voices at once, and a general awe pervaded the whole group. Eyes were then applied to the key-holes, and to every crevice in the window-shutters, when the rector was seen beckoning his old terrified housekeeper to sit still and silent. A simultaneous shout convinced him that his design was under-stood. Still he consoled himself with the hope that his larder and his cellar were secure, as the house could not be entered. But his hope was speedily dissipated. Ladders were reared against the roof, tiles were hastily thrown off, half-a-dozen sturdy young men entered, rushed down the stairs, and threw open both the outer-doors. In a trice, a hundred or more unwelcome visitors rushed into the house, and began unceremoniously to help themselves to such fare as the larder and cellar afforded; for no special stores having been provided for the occasion, there was not half enough bread and cheese for such a multitude. To the rector and his housekeeper, that festival was converted into the most rigid fast-day they had ever observed. After this signal triumph, the parishioners of Drayton regularly exercised their 'privilege of Stephening' till the incumbency of the Rev. Basil Wood, who was presented to the living in 1808. Finding that the custom gave rise to much rioting and drunkenness, he discontinued it, and distributed instead an annual sum of money in proportion to the number of claimants. But as the population of the parish greatly increased, and as he did not consider himself bound to continue the practice, he was induced, about the year 1827, to withhold his annual payments; and so the custom became finally abolished. For some years, however, after its discontinuance, the people used to go to the rectory for the accustomed bounty, but were always refused. In the year 1834, the commissioners appointed to inquire concerning charities, made an investigation into this custom, and several of the inhabitants of Drayton gave evidence on the occasion, but nothing was elicited to shew its origin or duration, nor was any legal proof advanced skewing that the rector was bound to comply with such a demand.* Many of the present inhabitants of the parish remember the custom, and some of them have heard their parents say, that it had been observed: As long as the sun had shone, And the waters had run. In London and other places, St. Stephen's Day, or the 26th of December, is familiarly known as Boxing-day, from its being the occasion on which those annual guerdons known as Christmas-boxes are solicited and collected. For a notice of them, the reader is referred to the ensuing article. CHRISTMAS-BOXESThe institution of Christmas-boxes is evidently akin to that of New-year's gifts, and, like it, has descended to us from the times of the ancient Romans, who, at the season of the Saturnalia, practiced universally the custom of giving and receiving presents. The fathers of the church denounced, on the ground of its pagan origin, the observance of such a usage by the Christians; but their anathemas had little practical effect, and in process of time, the custom of Christmas-boxes and New-year's gifts, like others adopted from the heathen, attained the position of a universally recognised institution. The church herself has even got the credit of originating the practice of Christmas-boxes, as will appear from the following curious extract from The Athenian Oracle of John Dunton; a sort of primitive Notes and Queries, as it is styled by a contributor to the periodical of that name. Q. From whence comes the custom of gathering of Christmas-box money? And how long since? A. It is as ancient as the word mass, which the Romish priests invented from the Latin word mitto, to send, by putting the people in mind to send gifts, offerings, oblations; to have masses said for everything almost, that no ship goes out to the Indies, but the priests have a box in that ship, under the protection of some saint. And for masses, as they cant, to be said for them to that saint, &c., the poor people must put in something into the priest's box, which is not to be opened till the ship return. Thus the mass at that time was Christ's-mass, and the box Christ's-mass-box, or money gathered against that time, that masses might be made by the priests to the saints, to forgive the people the debaucheries of that time; and from this, servants had liberty to get box-money, because they might be enabled to pay the priest for masses-because, No penny, no paternoster-for though the rich pay ten times more than they can expect, yet a priest will not say a mass or anything to the poor for nothing; so charitable they generally are.' The charity thus ironically ascribed by Dunton to the Roman Catholic clergy, can scarcely, so far as the above extract is concerned, be warrantably claimed by the whimsical author himself. His statement regarding the origin of the custom under notice may be regarded as an ingenious conjecture, but cannot be deemed a satisfactory explanation of the question. As we have already seen, a much greater antiquity and diversity of origin must be asserted. This custom of Christmas-boxes, or the bestowing of certain expected gratuities at the Christmas season, was formerly, and even yet to a certain extent continues to be, a great nuisance. The journeymen and apprentices of trades-people were wont to levy regular contributions from their masters' customers, who, in addition, were mulcted by the trades-people in the form of augmented charges in the bills, to recompense the latter for gratuities expected from them by the customers' servants. This most objectionable usage is now greatly diminished, but certainly cannot yet be said to be extinct. Christmas-boxes are still regularly expected by the postman, the lamplighter, the dustman, and generally by all those functionaries who render services to the public at large, without receiving payment therefore from any particular individual. There is also a very general custom at the Christmas season, of masters presenting their clerks, apprentices, and other employees, with little gifts, either in money or kind. St. Stephen's Day, or the 26th of December, being the customary day for the claimants of Christmas-boxes going their rounds, it has received popularly the designation of Boxing-day. In the evening, the new Christmas pantomime for the season is generally produced for the first time; and as the pockets of the working-classes, from the causes which we have above stated, have commonly received an extra supply of funds, the theatres are almost universally crowded to the ceiling on Boxing-night; whilst the 'gods,' or upper gallery, exercise even more than their usual authority. Those interested in theatrical matters await with consider-able eagerness the arrival, on the following morning, of the daily papers, which have on this occasion a large space devoted to a chronicle of the pantomimes and spectacles produced at the various London theatres on the previous evening. In conclusion, we must not be too hard on the system of Christmas-boxes or handsets, as they are termed in Scotland, where, however, they are scarcely ever claimed till after the commencement of the New Year. That many abuses did and still do cling to them, we readily admit; but there is also intermingled with them a spirit of kindliness and benevolence, which it would be very undesirable to extirpate. It seems almost instinctive for the generous side of human nature to bestow some reward for civility and attention, and an additional incentive to such liberality is not infrequently furnished by the belief that its recipient is but inadequately remunerated otherwise for the duties which he performs. Thousands, too, of the commonalty look eagerly forward to the forth-coming guerdon on Boxing-day, as a means of procuring some little unwonted treat or relaxation, either in the way of sight-seeing, or some other mode of enjoyment. Who would desire to abridge the happiness of so many? CHRISTMAS PANTOMIMESPantomimic acting had its place in the ancient drama, but the grotesque performances associated with our English Christmas, are peculiar to this country. Cibber says that they originated in an attempt to make stage-dancing something more than motion without meaning. In the early part of the last century, a ballet was produced at Drury Lane, called the Loves of Mars and Venus, wherein the passions were so happily expressed, and the whole story so intelligibly told by a mute narration of gesture only, that even thinking spectators allowed it both a pleasing and rational entertainment. From this sprung forth that succession of monstrous medleys that have so long infested the stage, and which arise upon one another alternately at both houses, outlying in expense, like contending bribes at both sides at an election, to secure a majority of the multitude.' Cibber's managerial rival, Rich, found himself unable, with the Lincoln's-Inn-Fields' company, to compete with Drury Lane in the legitimate drama, and struck out a path of his own, by the invention of the comic pantomime. That he was indebted to Italy for the idea, is evident from an advertisement in the Daily Courant, for the 26th December 1717, in which his Harlequin Executed is described as 'A new Italian Mimic Scene (never performed before), between a Scaramouch, a Harlequin, a Country Farmer, his Wife, and others.' This piece is generally called 'the first English pantomime' by theatrical historians; but we find comic masques 'in the high style of Italy,' among the attractions of the patent-houses, as early as 1700. Rich seems to have grafted the scenic and mechanical features of the old masque upon the pantomimic ballet. Davies, in his Dramatic Miscellanies, describes Rich's pantomimes as 'consisting of two parts-one serious, the other comic. By the help of gay scenes, fine habits, grand dances, appropriate music, and other decorations, he exhibited a story from Ovid's Metamorphoses, or some other mythological work. Between the pauses or acts of this serious representation, he interwove a comic fable, consisting chiefly of the courtship of Harlequin and Columbine, with a variety of surprising adventures and tricks, which were produced by the magic wand of Harlequin; such as the sudden transformation of palaces and temples to huts and cottages; of men and women into wheel-barrows and joint-stools; of trees turned to houses; colonnades to beds of tulips; and mechanics' shops into serpents and ostriches.' Pope complains in The Dunciad, that people of the first quality go twenty and thirty times to see such extravagances as: A sable sorcerer rise, Swift to whose hand a winged volume flies: All sudden, gorgons hiss and dragons glare, And ten-horned fiends and giants rush to war. Hell rises, Heaven descends, and dance on earth, Gods, imps and monsters, music, rage, and mirth, A fire, a jig, a battle and a ball, Till one wide conflagration swallows all. Thence a new world to Nature's laws unknown, Breaks out refulgent, with a heaven its own; Another Cynthia her new journey runs, And other planets circle other suns. The forests dance, the rivers upward rise, Whales sport in woods, and dolphins in the skies; And last, to give the whole creation grace, Lo! one vast egg produces human race. The success of the new entertainment was wonder-fully lasting. Garrick and Shakespeare could not hold their own against Pantomime. The great actor reproaches his aristocratic patrons because: They in the drama find no joys, But doat on mimicry and toys. Thus, when a dance is in my bill, Nobility my boxes fill; Or send three days before the time, To crowd a new-made pantomime. And The World (1st March 1753) proposes that pantomime shall have the boards entirely to itself. 'People of taste and fashion have already given sufficient proof that they think it the highest entertainment the stage is capable of affording; the most innocent we are sure it is, for where nothing is said and nothing is meant, very little harm can be done. Mr. Garrick, perhaps, may start a few objections to this proposal; but with those universal talents which he so happily possesses, it is not to be doubted but he will, in time, be able to handle the wooden sword with as much dignity and dexterity as his brother Lun.' The essayist does Rich injustice; the latter's Harlequin was something more than a dexterous performance. Rich was a first-rate pantomimic actor, to whom words were needless. Garrick bears impartial witness to the genius of the exhibitor of the eloquence of motion. In the prologue to a pantomime with a talking-hero, produced after Rich's death, he says: 'Tis wrong, The wits will say, to give the fool a tongue. When Lun appeared, with matchless art and whim, He gave the power of speech to every limb; Though masked and mute, conveyed his quick intent, And told in frolic gestures all he meant. At this time the role of Harlequin was not considered derogatory to an actor as it is now-Woodward, who established his reputation by playing such characters as Lord Foppington, Marplot, and Sir Andrew Aguecheek, was equally popular as the party-coloured hero. In the hands of Lun's successors, Harlequin sadly degenerated; and when Grimaldi appeared upon the scene, his genius elevated the Clown into the principal personage of the pantomime. The harlequinade still remained the staple of the piece, the opening forming a very insignificant portion. John Kemble himself did not disdain to suggest the plot of a pantomime. Writing to Tom Dibdin, he says: 'The pantomime might open with three Saxon witches lamenting Merlin's power over them, and forming an incantation, by which they create a Harlequin, who is supposed to be able to counter-act Merlin in all his designs against King Arthur. If the Saxons come on in a dreadful storm, as they proceeded in their magical rites, the sky might brighten, and a rainbow sweep across the horizon, which, when the ceremonies are completed, should contract itself from either end, and form the figure of Harlequin in the heavens. The wizards may fetch him down as they will, and the sooner he is set to work the better.' Dibdin himself was a prolific pantomime author; and we cannot give a better idea of what the old-fashioned pantomime was, than by quoting the first scene of his Harlequin in his Element; or Fire, Water, Earth, and Air, performed at Covent Garden Theatre in 1807. The dramatis persona consist of Ignoso, the spirit of Fire; Aquina, the fairy of the Fountain; Aurino, genius of Air; Terrena, spirit of Earth; Harlequin (Mr Bologna, Jr.); Columbine (Miss Adams); Sir Amoroso Sordid, guardian to Columbine (Mr Ridgway); and Gaby Grin, his servant (Mr Grimaldi). SCENE IA beautiful garden, with terraces, arcades, fountains, &c. The curtain rises to a soft symphony. Aurino is seen descending on a light cloud; he approaches a fountain in the centre of the garden, and begins the following duet: Aquina! Fountain Fairy! The genius of the Air Invites thee here From springs so clear, With love to banish care. AQUINA, rising from fountain. Aurino, airy charmer, Behold thy nymph appear. What peril can alarm her, When thou, my love, art near? Terrena rises from the earth, and addresses the other two. Why rudely trample thus on Mother Earth? Fairies, ye know this ground 's my right by birth. These pranks I'll punish: Water shall not rise Above her level; Air shall keep the skies. It thunders; IGNOSO descends. Tis burning shame, such quarrels 'mong you three, Though I warm you, you're always cold to Inc. The sons of Earth, on every slight disaster, Call me good servant, but a wicked master. Of Air and Water, too, the love I doubt, One blows me up, the other puts me out. Nay, if you're angry, I'll have my turn too, And you shall see what mischief I can do! Ignoso throws the fire from his wand; the flowers all wither, but are revived by the other fairies. Terrena speaks: Fire, why so hot? Your bolts distress not me, But injure the fair mistress of these bowers; Whose sordid guardian would her husband be, For lucre, not for love. Rather than quarrel, let us use our powers, And gift with magic aid some active sprite, To foil the guardian and the girl to right. Quartett. Igno: About it quick! Toss: This clod to form shall grow, Aqui: With dew refreshed Aur: With vital air Igno: And warm with magic glow. HARLEQUIN is produced from a bed of party-coloured flowers; the magic sword is given him, while he is thus addressed: Terr: This powerful weapon your wants will provide; Then trip, Aur: Free as air, Aqui: And as brisk as the tide. Igno: Away, while thy efforts we jointly inspire. Terr: Tread lightly! Aur: Fly! Aqui: Run! Igno: And you'll never hang fire! IGNOSO sinks. AQUINA strikes the fountains; they begin playing. TERRENA strikes the ground; a bed of roses appears. Harlequin surveys everything, and runs round the stage. Earth sinks in the bed of roses, and Water in the fountain. Air ascends in the car. Columbine enters dancing; is amazed at the sight of Harlequin, who retires from her with equal surprise; they follow each other round the fountain in a sort of pas de deux.' They are surprised by the entrance of Columbine's Guardian, who comes in, preceded by servants in rich liveries. Clown, as his running footman, enters with a lapdog. Old Man takes snuff views himself in a pocket-glass. Clown imitates him, &c. Old Man sees Harlequin and Columbine, and pursues them round the fountains, but the lovers go of, followed by Sir Amonoso and servants. And so the lovers are pursued by Sir. Amoroso and Clown through sixteen scenes, till the fairies unite them in the Temple of the Elements. The harlequinade-left is full of practical jokes, but contains no hits at the follies of the day throughout it all; the relative positions of Clown and Sir Amoroso, Pantaloon, or the Guardian (as he is styled indifferently), as servant and master, are carefully preserved. Since Dibdin's time, the pantomime has under-gone a complete change. The dramatic author furnishes only the opening, which has gradually become the longest part of the piece; while the harlequinade-left to the so-called pantomimists to arrange-is nothing but noise. Real pantomime-acting is eschewed altogether; Harlequin and Columbine are mere dancers and posturers; and Clown, if he does not usurp the modern Harlequin's attribute, is but a combination of the acrobat and coarse buffoon. The pantomime of the present day would certainly not be recognized by Rich or owned by Grimaldi. STEPHEN GIRARDIn a country, destitute of a titled and hereditary aristocracy, wealth is distinction. The accumulation of great wealth is evidence of strong character; and when the gathered riches are well used and well bestowed, they give celebrity and even renown. Stephen Girard was the son of a common sailor of Bourdeaux, France, and was born May 21st, 1750. At the age of ten he went, a cabin-boy, to New York, where he remained in the American coasting trade until he became master and part-owner of a small vessel, while he was still a youth. During the American Revolution, he kept a grocery and liquor-shop in Philadelphia, and made money enough from the American and British armies, as they successively occupied the city, to embark largely in trade with the West Indies. Fortune comes at first by slow degrees. The first thousand pounds is the step that costs. Then, in good hands, capital rolls up like a snow-ball. In 1790, Girard had made £6000. Now the golden stream began to swell. The misfortunes of others were his gain. At the time of the terrible massacre of St. Domingo, he had some ships in a harbour of that island. The planters sent their plate, money, and valuables on board his vessels, and were pre-paring to embark, with their families, when they were massacred by the infuriated negroes. Property to the value of £10,000 was left in the hands of Guard, for which he could find no owners. He married, but unfortunately, and soon separated from his wife, and he had no children and no friends. Yet this hard, money-making man was a hero in courage and in charity. When professing Christians fled from the yellow fever in Philadelphia, in 1793, 1797, and 1798, Girard, who had no religious belief, stayed in the city, and spent day and night in taking care of the sick and dying. As his capital accumulated, he became a banker; and when the United States government, in the war of 1812 with England, wanted a loan of £1,000,000, and only got an offer of £4000, Girard undertook the entire loan. When he died, December 26, 1831, he left £1,800,000, nearly the whole of which was bequeathed to charitable institutions, £400,000 being devoted to the foundation of a college for orphan boys. The buildings of this college, in the suburbs of Philadelphia, are constructed of white marble, in the Grecian style, and are among the most beautiful in the world. Girard was a plain, rude man, without education, frugal and friendless; yet kind to the sick, generous to the poor, and a benefactor to the orphan. LONDON LIFE A CENTURY AGOHogarth has bequeathed us the most perfect series of pictures possessed by any nation, of the manners and custom of its inhabitants, as seen by himself. They go lower into the depths of every-day life than is usually ventured upon by his brethren of the brush. The higher-class scenes of his 'Marriage a la Mode' teach us little more than we can gather from the literature of his era; but when we study 'Gin Lane' in all its ghastly reality, we see-and shudder in contemplating it -the abyss of vice and reckless profligacy into which so large a number of the lower classes had fallen, and which was too disgusting as well as too familiar, to meet with similar record in the pages of the annalist. There exists a curious octavo pamphlet-dedicated by its author to Hogarth himself-which minutely describes the occupation of the inhabit-ants of London during the whole twenty-four hours. It is unique as a picture of manners, and though rude in style, invaluable for the information it contains, and which is not to be met elsewhere. It appears to have been first published in 1759, and ran through several editions. It is entitled Low Life: or, One half the World knows not how the other half Live; and purports to be 'a true description of a Sunday as it is usually spent within the Bills of Mortality, calculated for the 21st day of June,' the anniversary (new style) of the accession of King George II. Mr. G. A. Sala, in his volume entitled Twice Round the Clock, acknowledges that his description therein of the occupation of each hour of a modern London day, was suggested by the perusal of a copy of this old pamphlet, lent to him by Mr. Dickens, and which had been presented to that gentleman by another great novelist, Mr. Thackeray. Under such circumstances, we may warrantably assume that there is something valuable in this unpretentious brochure, and we therefore proceed to glean from it as much as may enable our readers to comprehend London life a century ago; premising that a great part of it is too gross, and a portion likewise too trivial, for modern readers. Our author commences his description at twelve o'clock on Saturday night, at which hour, he says: 'The Salop-man in Fleet Street shuts up his gossiping coffee-house.' [The liquid known as salop or saloop, kept hot, was at one time much sold at street-corners in London, but the demand ceased about thirty years since. It was made from an infusion of sassafras, and said to be very nutritive.] Almost the next incident reminds us of the old roguery and insecurity of London- 'watchmen taking fees from house-breakers, for liberty to commit burglaries within their beats, and at the same time promising to give them notice if there is any danger of their being taken, or even disturbed in their villanies.' The markets begin to swarm with the wives of poor journeymen shoemakers, smiths, tinkers, tailors, &c., who come to buy great bargains with little money. Dark-house Lane, near Billingsgate, in an uproar, with custom-house officers, sailors' wives, smugglers, and city-apprentices, waiting to hear the high-water bell ring, to go in the tilt-boat to Gravesend. [The journey to Gravesend was a serious adventure in those days, always occupying twelve hours, and frequently more; if the tide turned, the passengers met with great delay, and were sometimes put ashore far from their destination. The only accommodation in these open boats, was a litter of straw, and a sail-cloth over it.] Ballad-singers, who have encumbered the corners of markets several hours together, repairing to the houses of appointed rendezvous, that they may share with pickpockets what had been stolen from the crowd of fools, which had stood about them all the evening. Houses which are left open, and are running to ruin, filled with beggars; some of whom are asleep, while others are pulling down the timber, and packing it up to sell for firing to washerwomen and clear-starchers. Tapsters of public-houses on the confines of London, receiving pence and two pences from those Scottish citizens they have light to town from over the fields, and who were too drunk and fearful to come by themselves.' From two till three o'clock, our author notes: 'Most private shops in and about London (as there are too many), where Geneva is publicly sold in defiance of the act of parliament, filled with the worst classes. Young fellows who have been out all night on the ran-dan, stealing staves and lanterns from such watchmen as they find sleeping on their stands. The whole company of Finders (a sort of people who get their bread by the hurry and negligence of sleepy tradesmen), are marching towards all the markets in London, Westminster, and Southwark; to make a seizure of all the butchers, poulterers, green-grocers, and other market-people have left behind them, at their stalls and shambles, when they went away. Night-cellars about Covent Garden and Charing-Cross, fill'd with mechanics, some sleeping, others playing at cards, with dead-beer before them, and link-boys giving their attendance. Men who intend to pretend to walk thirty or forty miles into the country, preparing to take the cool of the morning to set out on their journeys. Vagabonds who have been sleeping under hay-ricks in the neighbouring villages and fields, awaken, begin to rub their eyes, and get out of their nests.' From three to four o'clock: 'Fools who have been up all the night, going into the fields with dogs and ducks, that they may have a morning's diversion at the noisy and cruel amusement. Pigeon-fanciers preparing to take long rambles out of London, to give their pigeons a flight. The bulks of tradesmen's houses crowded with vagabonds, who having been picking pockets, carrying links, fetching spendthrifts from taverns, and beating drunken-men, have now got drunk them-selves and gone to sleep Watchmen crying 'Past four o'clock,' at half-an-hour after three, being persuaded that scandalous pay deserves scandalous attendance. Poor people carrying their dead children, nailed up in small deal-boxes, into the fields to bury them privately, and save the extravagant charge of parish dues. The streets, at this time, are beginning to be quiet-the fishwomen gone to Billingsgate to wait the tide for the arrival of the mackerel-boats.' From four till five o'clock: 'Early risers, with pipes stuck in their jaws, walking towards Hornsey Wood, Dulwich Common, Marybone, and Stepney, in order to take large morning-draughts, and secure the first fuddle of the day. Beggars going to parish nurses, to borrow poor helpless infants at fourpence a day, and persuade credulous charitable people they are their own, and have been sometime sick and fatherless. The wives and servant-girls of mechanics and day-labourers, who live in courts and alleys, where one cock supplies the whole neighbourhood with water, taking the advantage before other people are up, to fill their tubs and pans with a sufficiency to serve them the ensuing seven days.' From five till six o'clock: 'The several new-built bun-houses about the metropolis, at Chelsea, Stepney, Stangate, Marybone, &c., are now open. People who keep she-asses about Brompton, Knightsbridge, Hoxton, and Stepney, getting ready to run with their cattle all over the town, to be milked for the benefit of sick and infirm persons. Poor people with fruit, nosegays, buns, &c., making their appearance. Petty equipages preparing to take citizens country journeys. The pump near St. Antholin's Church, in Watling Street, crowded with fishwomen who are washing their stinking mackerel, to impose them on the public for fish come up with the morning's tide. Bells tolling, and the streets beginning to fill with old women and charity-children, who attend the services of the church.' From six to seven o'clock: 'A great number of people of both sexes, especially fanciers and dealers in birds, at the Birds Nest Fair held every Sunday morning, during the season, on Dulwich Common. Beggars who have put on their woful countenances, and also managed their sores and ulcers so as to move compassion, are carrying wads of straw to the corners of the most public streets, that they may take their seats, and beg the charity of all well-disposed Christians the remaining part of the day.' From seven to eight o'clock: 'Country fellows, newly come to London, running about to see parish churches, and find out good ale and new acquaintances. Chairmen at the court-end of the town, fast asleep in their chairs, for want of business or a better lodging. Common people going to quack-doctors, and petty barbers, in order to be let blood (and perhaps have their arms lamed) for three-pence. Abundance of lies told in barbers' shops by those who come to be shaved, many fools taking those places to be the repositories of polite education. The whole cities of London, Westminster, and the borough of Southwark, covered by a cloud of smoke, most people being employed at lighting fires.' From eight to nine: 'People in common trade and life, going out of town in stage-coaches to Edmonton, Stratford, Deptford, Acton, &c.; trades-men who follow the amusement of angling, preparing to set out for Shepperton, Carshalton, Epping Forest, and other places of diversion; to pass away the two or three feast-days of the week. Servants to ladies of quality are washing and combing such lapdogs as are to go to church with their mistresses that morning.' From nine to ten: 'Pupils belonging to surgeons going about their several wards, letting blood, mending broken bones, and doing whatever else they think necessary for their poor patients. Citizens who take a walk in the morning, with an intent to sleep away the afternoon, creeping to Sadler's Wells, or Newington, in order to get drunk during the time of divine service. French artificers quit their garrets, and exchange their greasy woollen caps and flannel shirts for swords and ruffles; and please themselves with a walk in St. James's Park, the Temple, Somerset House gardens, Lincoln's Inn walks, or Gray's Inn; and then look sharp after an eleemosynary dinner at some dirty public-house. The new breakfasting-hut near Sadler's Wells, crowded with young fellows and their sweethearts, who are drinking tea and coffee, telling stories, repeating love-songs, and broken scraps of low comedy, till towards dinner-time. The great room at the 'Horns,' at Hornsey Wood, crowded with men, women, and children, eating rolls and butter, and drinking of tea, at an extravagant price.' From ten till eleven: 'Crowds of old country fellows, women, and children, about the lord-mayor's coach and horses, at the south side of St. Paul's Churchyard. Much business done on the custom - house quays, Temple piazzas, and the porch of St. Mary-le-Bow Church, in Cheapside, since the nave of St. Paul's has been kept clear, by order of the bishop of London. [This is a very curious notice of a very old custom, that of making the nave the scene of gossip and business, which prevailed in the days of Elizabeth, to the disregard of common decency in a sacred edifice, and which appears to have been customary even to this late date.] The churchyards about London, as Stepney, Pancras, Islington, &c., filled with people reading the tombstones, and eating currants and gooseberries. Actors and actresses meeting at their apartments to rehearse the parts they are to perform. Fine fans, rich brilliants, white hands, envious eyes, and enamelled snuff-boxes, displayed in most places of divine service, where people of fashion endure the intolerable fatigue with wonderful seeming patience.' From eleven till twelve: 'Poor French people, about the Seven Dials and Spitalfields, picking dandelion in the adjacent fields, to make a salad for dinner. The organ-hunters running about from one parish church to another, to hear the best masters, as Mr. Stanley, &c., play. [Mr. Stanley was the famous blind organist of the Temple church, and a friend of Handel. There is a portrait and memoir of him in the Europeans Magazine for 1784.] The wives of genteel mechanics, under pretence of going to prayers in their apartment, take a nap and a dram, after which they chew lemon-peel to prevent being smelt. Ladies about St. James's reading plays and romances, and making paint for their faces.' From twelve till one: 'Idle apprentices, who have played under gateways during the time of divine service, begging the text of old women at the church-doors to carry home to their inquisitive masters and mistresses. Young tradesmen, half-starved gentlemen, merchants' clerks, petty officers in the customs, excise, and news-collectors, very noisy over their half-pints and dumplings in tavern-kitchens about Temple Bar and the Royal Exchange. Nosegay-women, flying-fruiterers, and black-shoe boys come again into business as the morning service is over. The south side of the Royal Exchange, in Cornhill, very much crowded with gentlemen doing business and hearing news. The Mall, in St. James's Park, filled with French-men picking their teeth, and counting the trees for their dinner. All the common people's jaws in and about this great metropolis in full employment.' From one till two: 'The friends of criminals under sentence of death in Newgate, presenting money to the turnkeys to get to the sight of them, in order to take their last farewell, and present them with white caps with black ribbons, prayer-books, nosegays, and oranges, that they may make a decent appearance up Holborn, on the road to the other world. Church bells and tavern bells keep time with each other. Men and boys who intend to swim in the River Lea near Hackney, the ponds near Hampstead, and the river Thames near Chelsea, this afternoon, are setting out according to their appointments. Pickpockets take their stands at the avenues of public places, in hopes of making a good booty during the hurry of the afternoon.' From two till three: 'Strollers, posture-masters, puppet - show men, fiddlers, tumblers, and toy-women, packing up their affairs, and preparing to set out for such fairs as Wandsworth, &c., which will, according to the custom of the nation, begin the next day. Pawnbrokers' wives dressing them-selves in their customers' wearing-apparel, rings and watches, in order to make a gay appearance in the fields, when evening service is over. Citizens who have pieces of gardens in the adjacent villages, walking to them with their wives and children, to drink tea, punch, or bottled-ale; after which they load themselves with flowers for bean-pots; and roots, salads, and other vegetables for their suppers. The paths of Kensington, Highgate, Hampstead, Islington, Stepney, and Newington, found to be much pleasanter than those ofthe gospel.' From three till four: 'Tallow-chandlers who do business privately in back-cellars and upper-rooms to evade the king's duty, taking advantage of most people being at church, in the fields, or asleep, to make mould-candles, known by the name of 'running the buck.' A general jumble from one end of London to another of silks, cottons, printed linens, and calicoes. Merchants get into their counting-houses with bottles of wine, pipes and tobacco before them, studying schemes for the advancement of their several stocks, both in trade and the public funds.' From four till five: 'Home hundreds of people, mostly women and children, walking backward and forward on Westminster Bridge for the benefit of the air. Eel-pies most unmercifully devoured at Green's Ferry, Jeremy's Ferry, and Bromley Lock on the River Lea; and at Clay Hall, near Old Ford, at Bow. The office-keepers of the Theatres Royal, tracing the streets from the houses of noblemen, ladies, and the principal actors and actresses, to let them know what is to be performed the ensuing day. The cider-cellar, in Spring Gardens, crowded with people of all nations.' From five till six: 'People who have the conveniency of flat leaded roofs on the tops of their houses, especially such as have prospects of the river Thames, drinking tea, beer, punch, and smoking tobacco there till the dusk of the evening. Well-dressed gentlewomen, and ladies of quality, drove out of St. James's Park, Lincoln's Inn Gardens, and Gray's Inn Walks, by milliners, mantua-makers, sempstresses, stay-makers, clear-starchers, French barbers, dancing masters, gentle-men's gentlemen, tailors' wives, conceited old maids, and butchers' daughters. Great numbers of footmen near the gate-entrance of Hyde Park, wrestling, cudgel-playing, and jumping; while others who have drank more than their share are swearing, fighting, or sleeping, till their ladies return from the Ring.' From six till seven: 'Children in back-alleys and narrow passages very busy at their several doors, shelling pease and beans for supper; and making boats, as they call them, with bean-shells Man deal-matches. New milk and biscuits plentifully attacked by old women, children, and fools, in St. James's Park, Lamb's Conduit Fields, and St George's Fields, Southwark. Westminster Abbey crowded with people, who are admiring the monuments, and reading their inscriptions.' From seven tilt eight: 'Fishermen out with their boats on the river Thames, and throwing out their nets to catch under-sized fish, contrary to act of parliament. The drawers at Sadler's Wells, and the Prospect House, near Islington; Jenny's Whim at Chelsea; the Spring Gardens at Newington and Stepney; the Castle at Kentish Town; and the Angel at Upper Holloway; in full employment, each of them trying to cheat, not only the customers, but even the person who has the care of the bar; and every room in those houses filled with talk and smoke. The taverns about the Royal Exchange filled with merchants, under-writers, and principal tradesmen, who oftentimes do as much business on the Sunday evenings, as they do when they go upon the Exchange. From eight to nine: 'Black eyes and broken heads exhibited pretty plentifully in the public streets, about precedency. Great struggling at Paris-Garden stairs, and the Barge-House stairs in Southwark, to get into the boats that ply to and from Blackfriars and the Temple. Young highwaymen venturing out upon the road, to attack such coaches, chaises, and horsemen as they think are worth meddling with on their return to London.' From nine till ten: 'Masters of private mechanic families reading to them chapters from The Whole Duty of Man before they go to bed. The streets hardly wide enough for numbers of people, who about this time are reeling to their habitations. Great hollowing and whooping in the fields, by such persons as have spent the day abroad, and are now returning home half-drunk, and in danger of losing their company.' From ten till eleven: 'Link-boys who have been asking charity all day, and have just money sufficient to buy a torch, taking their stands at Temple Bar, London Bridge, Lincoln's-Inn-Fields, Smithfield, the City Gates, and other public, places, to light, knock down, and rob people. The gamins tables at Charing Cross, Covent Garden, Holborn, and the Strand, begin to fill with men of desperate fortunes, bullies, fools, and gamesters.' From eleven till twelve: 'People of quality leaving off gaming in order to go to supper. Night-houses begin to fill. One-third of the inhabitants of London fast asleep, and almost penniless. The watch-houses begin to fill with young fellows shut out of their apartments, who are proud of sitting in the constable's chair, holding the staff of authority, and sending out for liquor to treat the watchmen. Bell-ringers assembling at churches to usher in the 22nd of June, the day of the king's accession.' Such are a few of the items illustrative of past manners, afforded by a pamphlet characterised by Mr. Sala as 'one of the minutest, the most graphic, the most pathetic pictures of London life a century since that has ever been written.' The author tells us that he chose Sunday for his descriptive day, in order that he might not be accused of any invidious choice 'hardly can it be expected that the other six begin or end in a more exemplary manner.' To the third edition of 1764 is appended a picture of St. Monday, that universal day of debauch among the working classes. Here we see tradesmen of all denominations idling and drinking, while a busy landlady chalks up double scores. Each man is characterized by some emblem of his trade.  To the left, a shoemaker and tailor are seated on a bench, the former threatening his ragged wife, who urges him home, with the strap; the tailor quietly learns a new song. The butcher, busy at cards, has his game deranged by a termagant wife, who proceeds to blows. The sturdy porter in front defies the staggering leather-cutter, who upsets the painter's colours; the painter, stupidly drunk on a bench behind, is still endeavoring to lift another glass. On the walls, 'King Charles's Golden Rules' are hung up with all the pretentious morality of low haunts; another paper, inscribed 'Pay to-day, I trout to-morrow,' is the most likely to be appealed to and enforced by the busy hostess. We gather from this slight review of a curious work, that London hours were earlier, and London habits in some degree more natural, as regards rising and walking, than among ourselves; but we also see greater coarseness of manners, and insecurity of life and property. Altogether, we may congratulate ourselves on the changes that a century has produced, and leave to unreasoning sentimentalists the office of bewailing the 'good old times' |