25th MarchBorn: Archbishop John Williams, 1582, Aberconæay; Bishop George Bull, 1634, Wells; Sir Richard Cox, Lord Chancellor of Ireland, 1650, Bandon; Joachim Murat, King of Naples, 1771, Bastide Frontonière. Died: Sir Thomas Elyot, eminent English writer, temp; Henry VIII, 1546; Bishop Aldrich, 1556, Horn-castle; Archbishop John Williams, 1650, Llandegay; Henry Cromwell, fourth son of the Protector, 1674, Soham, Cambridgeshire; Nehemiah Grew, celebrated for his work on the Anatomy of Vegetables, 1711; Anna Seward, miscellaneous writer, 1809, Lichfield. THE ANNUNCIATION OF THE BLESSED VIRGIN MARYThis day is held in the Roman Catholic Church as a great festival, in the Anglican Reformed Church as a feast, in commemoration of the message of the angel Gabriel to the Virgin Mary, informing her that the Word of God was become flesh. In England it is commonly called Lady Day; in France, Notre Dame de Maas. It is a very ancient institution in the Latin Church. Among the sermons of St. Augustine, who died in 430, are two regarding the festival of the Annunciation. 'In representations of the Annunciation, the Virgin Mary is shewn kneeling, or seated at a table reading. The lily (her emblem) is usually placed between her and the angel Gabriel, who holds in one hand a sceptre surmounted by a fleur-de-lis, on a lily stalk; generally a scroll is proceeding from his mouth with the words Ave Maria gratiâ plenâ; and sometimes the Holy Spirit, represented as a clove, is seen descending towards the Virgin.'-Calendar of the Anglican Church. In the work here quoted, we find a statement affording strong proof of the high veneration in which the Virgin was formerly held in England, as she still is in Catholic countries; namely, that no fewer than two thousand one hundred and twenty churches were named in her sole honour, besides a hundred and two in which her name was associated with that of some other saint. GOOD FRIDAYThe day of the Passion has been held as a festival by the Church from the earliest times. In England, the day is one of two (Christmas being the other) on which all business is suspended. In the churches, which are generally well attended, the service is marked by an unusual solemnity. Before the change of religion, Good Friday was of course celebrated in England with the same religious ceremonies as in other Catholic countries. A dressed figure of Christ being mounted on a crucifix, two priests bore it round the altar, with doleful chants; then, laying it on the ground with great tenderness, they fell beside it, kissed its hands and feet with piteous sighs and tears, the other priests doing the like in succession. Afterwards came the people to worship the assumedly dead Saviour, each bringing some little gift, such as corn and eggs. There was finally a most ceremonious burial of the image, along with the 'singing bread,' amidst the light of torches and the burning of incense, and with flowers to strew over the grave. The king went through the ceremony of blessing certain rings, to be distributed among the people, who accepted them as infallible cures for cramp. Coming in state into his chapel, he found a crucifix laid upon a cushion, and a carpet spread on the ground before it. The monarch crept along the carpet to the crucifix, as a token of his humility, and there blessed the rings in a silver basin, kneeling all the time, with his almoner likewise kneeling by his side. After this was done, the queen and her ladies came in, and likewise crept to the cross. The blessing of cramp-rings is believed to have taken its rise in the efficacy for that disease supposed to reside in a ring of Edward the Confessor, which used to be kept in Westminster Abbey. There can be no doubt that a belief in the medical power of the cramp-ring was once as faithfully held as any medical maxim whatever. Lord Berners, the accomplished translator of Froissart, while ambassador in Spain, wrote to Cardinal Wolsey, June 21, 1518, entreating him to reserve a few cramprings for him, adding that he hoped, with God's grace, to bestow them well. A superstition regarding bread baked on Good Friday appears to have existed from an early period. Bread so baked was kept by a family all through the ensuing year, under a belief that a few gratings of it in water would prove a specific for any ailment, but particularly for diarrhea. We see a memorial of this ancient superstition in the use of what are called hot cross-buns, which may now be said to be the most prominent popular observance connected with the day. In London, and all over England (not, however, in Scotland), the morning of Good Friday is ushered in with a universal cry of Hot Cross-Buns! A parcel of them appears on every break-fast table. It is a rather small bun, more than usually spiced, and having its brown sugary surface marked with a cross. Thousands of poor children and old frail people take up for this day the business of disseminating these quasi-religious cakes, only intermitting the duty during church hours; and if the eagerness with which young and old eat them could be held as expressive of an appropriate sentiment within their hearts, the English might be deemed a pious people. The ear of every person who has ever dwelt in England is familiar with the cry of the street bun-vendors: One a penny, buns, Two a penny, buns, One a penny, two a penny, Hot cross-buns! Whether it be from failing appetite, the chilling effects of age, or any other fault in ourselves, we cannot say; but it strikes us that neither in the bakers' shops, nor from the baskets of the street-vendors, can one now get hot cross-buns comparable to those of past times. They want the spice, the crispness, the everything they once had. Older people than we speak also with mournful affection of the two noted bun-houses of Chelsea. Nay, they were Royal bun-houses, if their signs could be believed, the popular legend always insinuating that the King himself had stopped there, bought, and eaten. of the buns. Early in the present century, families of the middle classes walked a considerable way to taste the delicacies of the Chelsea bun-houses, on the seats beneath the shed which screened the pavement in front. An insane rivalry, of course, existed between the two houses, one pretending to be The Chelsea Bun-house, and the other the Real Old Original Chelsea Bun-house. Heaven knows where the truth lay, but one thing was certain and assured to the innocent public, that the buns of both were so very good that it was utterly impossible to give an exclusive verdict in favour of either. A writer, signing himself H. C. B., gives in the Athenaeum for April 4, 1857, an account of an ancient sculpture in the Museo Borbonico at Rome, representing the miracle of the five barley loaves. The loaves are marked each with a cross on the surface, and the circumstance is the more remarkable, as the hot cross-bun is not a part of the observance of the day on the Continent. H. C. B. quotes the late Rev. G. S. Faber for a train of speculation, having for its conclusion that our eating of the hot cross-buns is to be traced back to a pagan custom of worshipping the Queen of Heaven with cakes-a custom to be found alike in China and in ancient Mexico, as well as many other countries. In Egypt, the cakes were horned to resemble the sacred heifer, and thence called boas, which in one of its oblique cases is boun-in short, bun! So people eating these hot cross-buns little know what, in reality, they are about. WASHING MOLLY GRIMEIn the church of Glentham, Lincolnshire, there is a tomb with a figure, popularly called Molly Grime; and this figure was regularly washed every Good Friday by seven old maids of Glentham, with water brought from Newell Well, each receiving a shilling for her trouble, in consequence of an old bequest connected with some property in that district. About 1832, the property being sold without any reservation of the rent-charge of this bequest, the custom was discontinued. GOOD FRIDAY IN ROMEAt Rome, the services in the churches on Good Friday are of the same solemn character as on the preceding day. At the Sistine Chapel, the yellow colour of the candles and torches, and the nakedness of the Pope's throne and of the other seats, denote the desolation of the church. The cardinals do not wear their rings; their dress is of purple, which is their wearing colour; in like manner, the bishops do not wear rings, and their stockings are black. The mace, as well as the soldiers' arms, are reversed. The Pope is habited in a red cope; and he neither wears his, ring nor gives his blessing. A sermon is preached by a conventual friar. Among other ceremonies, which we have not space to describe, the crucifix is partially unveiled, and kissed by the Pope, whose shoes are taken off on approaching, to do it homage. A procession takes place (across a vestibule) to the Paolina Chapel, where mass is celebrated by the Grand Penitentiary. In the afternoon, the last Miserere is chanted in the Sistine Chapel, on which occasion the crowding is very great. After the Miserere, the Pope, cardinals, and other clergy, proceed through a covered passage to St. Peter's, in order to venerate the relics of the True Cross, the Lance, and the Volta Santo, which arc shewn by the canons from the balcony above the statue of St. Veronica. Notwithstanding the peculiar solemnity of the religious services of the day, the shops, public offices, and places of business, also the palazzos where galleries of pictures are shewn, are open as usual-the only external indications of the religious character of the day being the muteness of the bells. This disregard of Good Friday at Rome contrasts strangely with the fact, that Roman Catholics shut their shops and abstain from business on that day in Scotland and other countries where it is in no respect a legal non dies. THE MYSTERY PLAY OF GOOD FRIDAY AT MONACOThe principality of Monaco is one of the smallest, yet one of the prettiest, possessions in the world. Three short streets, an ancient chateau well fortified, good barracks, a tolerably large square or place, a church, and fine public gardens, placed on a rock which descends perpendicularly into the Mediterranean five hundred feet deep, and you have there the whole of this Lilliputian principality. High mountains rise behind the town, and shelter it from the north wind, whilst the mildness of the climate is attested by the vigorous growth of the palm trees and cactus, which stretches its knotty arms, set with thorns, over the rocks, reminding the passer-by of beggars who hold out their malformations or solicit attention by their contortions. The mountain tops dazzle you with their snowy mantle, whilst the gardens are filled with the sweet perfume of Bengal roses, orange blossom, geraniums, and Barbary figs, which seem to have found here their natal soil. This little spot was given in the tenth century to the Grimaldi family, of Genoa, by a special favour of the Emperor, but it was a source of continual jealousy; the Republic of Genoa attacking it on the one side, and Charles of Anjou on the other. In 1300 it was restored to the Grimaldi, but shortly after fell into the hands of the Spinolas, an equally illustrious Genoese family, when it became one of the centres for the Ghibellin faction. Yet in 1329 it was restored to its rightful owners, and remained in their hands by the female side up to the last prince. The chateau is an interesting edifice of the middle ages, with its two towers and double gallery of arcades. The court is large, and adorned with fine frescoes by Horace de Ferrari; whilst the staircase is as magnificent as that at Fontainebleau, and entirely of white marble. We will enter this little city with the crowd of strangers which the procession of Good Friday annually collects. When the services of the evening are over, about nine o'clock preparations arc made for a display which is allegorical, symbolical, and historical; the intention is to depict the different scenes of Christ's passion, and his path to the cross. The members of a brotherhood act the different parts, and a special house preserves the costumes, decorations, lay figures, and other articles necessary for the representation. Torches are lighted, and the drums of the national guard supply the place of bells, which are wanting. There are numbers of stations on the way to Calvary, and a different scene enacted at each; the same person who represents Christ does not do so throughout, but there is one who drinks the vinegar, another who is scourged, another bears the cross. Each is re-presented by an old man with white hair and beard, clothed in scarlet robes, a crown of thorns, and the breast painted with vermilion to imitate drops of blood. The four doctors of the law wear black robes and an advocate's cap; from time to time they draw a large book from their pocket, and appearing to consult together, shew by significant gestures that the text of the law is decisive, and they can do no other than condemn Jesus. Pontius Pilate is near to them, escorted by a servant, who carries a large white parasol over his head; whilst the Roman prefect wears the dress of the judge of an assize court, short breeches and a black toga. Behind this majestic personage walks a slave in a large white satin mantle, carrying a silver ewer, which he presents to the Governor when he pronounces the words 'I wash my hands of it.' King Herod is not forgotten in the group; he will be recognised by his long scarlet mantle, his wig with three rows of curls, his grand waistcoat, and gilt paper crown placed on his grey hair. Then comes the Colonel of Pontius Pilate's Army (so described in the list), distinguished by his great height and extreme leanness: his white trousers were fastened round his legs after the fashion of the Gauls, he had a Roman cuirass, the epaulettes of a general, a long rapier, white silk stockings, a gigantic helmet, over which towered a still higher plume of feathers. This military figure was mounted on a horse of the small Sardinian breed, so that the legs of the rider touched the ground. St. Peter with the cock, Thomas the incredulous, the Pharisees and Scribes, were all there; none were forgotten. As for Judas, his occupation consisted in throwing himself every moment into his master's arms, and kissing him in a touching manner. Adam and Eve must not be forgotten, under the form of a young boy and girl, in costumes of Louis Quinze, with powdered wigs, and eating apples off the bough of an orange tree! The procession advances; the Jewish nation, represented by young persons dressed in blue blouses with firemen's helmets, form in rank to insult the martyred God as he passes. Here it is a tall rustic who gives him a blow with his fist; there a woman offers vinegar and gall; still further, the Roman soldiers, at a signal from the beadle, throw themselves forward, lance in hand, and make a feint of piercing him with sanguinary fury, drawing back only to repeat the same formidable movement. The Jews brandish menacing axes, whilst the three Maries, dressed in black, their faces covered with lugubrious veils, weep and lament bitterly. Finally, there is Christ on the cross, and Christ laid in the tomb; but this part of the scene is managed by puppets suitably arranged. If we place all these scenes in the narrow old streets of Monaco, passing through antique arcades, and throw over the curious spectacle the trembling light of a hundred torches and a thou-sand wax lights, the stars shining in the dark blue sky, the distant chanting of the monks, the charm of mystery and poetry, and the scent of orange blossoms and geraniums, we shall feel that we have retrograded many centuries, and can fancy ourselves transported into the dark middle ages, to the time when the mystery plays, of which this is a relic, replaced the Greek tragedy. THE HOLY COAT OF TREBES

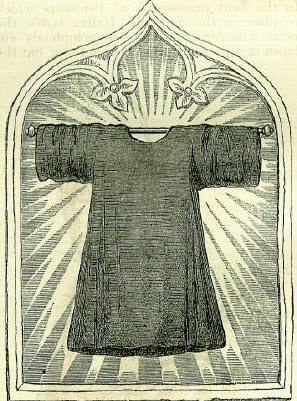

The ancient archiepiscopal city of Treves, on the Moselle, is remarkable for possessing among its cathedral treasures, the coat reputed to be that worn by the Saviour at his execution, and for which the soldiers cast lots. Its history is curious, and a certain antiquity is connected with it, as with many other 'relics' exhibited in the Roman Catholic Church, and which gives them an interest irrespective of their presumed sacred character. This coat was the gift of the famed Empress Helena, the mother of Constantine the Great, and the 'discoverer' of so large a number of memorials of the founders of Christianity. In her day, Treves was the capital of Belgic Gaul, and the residence of the later Roman Emperors; it is recorded that she converted her palace into the Cathedral, and endowed it with this treasure -the seamless coat of the Saviour. That it was a treasure to the Cathedral and city is apparent from the records of great pilgrimages performed at intervals during the middle ages, when this coat was exhibited; each pilgrim offered money to the shrine, and the town was enriched by their general expenditure. Unlike other famed relics, this coat was always exhibited sparingly. The Church generally displays its relics at intervals of a few years, but the Holy Coat was only seen once in a century; it was then put away by the chief authorities of the Cathedral in some secret place known only to a few. In Murray's Hand-book for Travellers, 1841, it is said, 'The existence of this relic, at present, is rather doubtful-at least, it is not visible; the attendants of the church say it is walled up.' All doubts were soon after removed, for in 1844 the Archbishop Arnoldi announced a centenary jubilee, at which the Holy Coat was to be exhibited. It produced a great effect, and Treves exhibited such scenes as would appear rather to belong to the fourteenth than the nineteenth century. Pilgrims came from all quarters, many in large bands preceded by banners, and marshalled by their village priests. It was impossible to lodge the great mass of these foot-sore travellers, and they slept on inn-stairs, in outhouses, or even in the streets, with their wallets for their pillows. By the first dawn they took up their post by the Cathedral doors; and long before these were opened, a line of many hundreds was added: sometimes the line was more than a mile in length, and few persons could reach the high altar where the coat was placed in less time than three hours. The heat, dust, and fatigue were too much for many, who fainted by the way; yet hour after hour, a dense throng passed round the interior of the Cathedral, made their oblation, and retired. The coat is a loose garment with wide sleeves, very simple in form, of coarse material, dark brown in colour, probably the result of its age, and entirely without seam or decoration. Our cut is copied from the best of the prints published at Treves during the jubilee, and will convey a clear impression of a celebrated relic which few are destined to examine. The dimensions given on this engraving state that the coat measures from the extremity of each sleeve, 5 feet 5 inches; the length from collar to the lowermost edge being 5 feet 2 inches. In parts it is tender, or threadbare; and some few stains upon it are reputed to be those of the Redeemer's blood. It is reputed to have worked many miracles in the way of cures, and its efficacy has never been doubted in Treves. The éclat which might have attended the exhibition of 1844, was destined to an opposition from the priestly ranks of the Roman Catholic Church itself. Johann Ronge, who already had become conspicuous as a foremost man among the reforming clergy of Germany, addressed an eloquent epistle to the Archbishop of Treves, indignantly denouncing a resuscitation of the superstitious observances of the middle ages. This letter produced much effect, and so far excited the wrath of Rome, that Rouge was excommunicated; but he was far from weakened thereby. Before the January of the following year he was at the head of an organized body of Catholics prepared to deny the supremacy of Rome; but the German governments, alarmed at the spread of freedom of opinion, suppressed the body thus called into vitality, and Rouge was ultimately obliged to leave his native land. In 1850 he came to England, and it is somewhat curious to reflect that the bold priest who alarmed Rome, lives the quiet life of a teacher in the midst of busy London, very few of whose inhabitants are conversant with the that of his residence. among them. PENITENT WITH CROWN OF THORNS

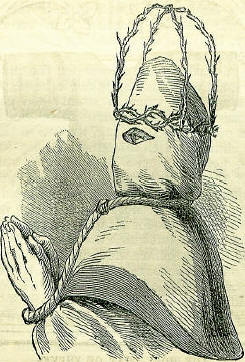

In the Lent processions of Penitents which take place in the Southern Italian states, the persons who form them are so completely enveloped in a peculiar dress that nothing but the eyes and hands are visible. A long white gown covers the body, and a high pointed hood envelops the head, spreading like a heavy tippet over the shoulders; holes are cut to allow of sight, but there are none for breathing. The sketch here engraved was made at Palermo, in Sicily, on the Good Friday of 1861, and displays these peculiarities, with the addition of others, seldom seen even at Rome. Each penitent in the procession wore upon the hood a crown of thorns twisted round the brow and over the head. A thick rope was passed round the neck, and looped in front of the breast, in which the uplifted hands of the penitent rested in the attitude of prayer. Thus, deprived of the use of hands and almost of sight, the slow movement of these lines of penitents through the streets was regulated by the clerical officials who walked beside and marshalled them. |