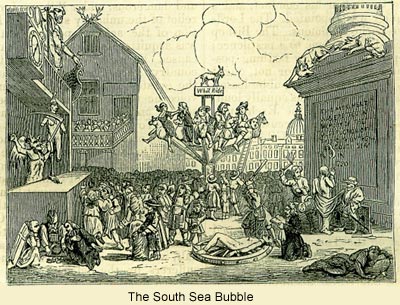

22nd JanuaryBorn: Francis Bacon, Lord Verulam, 1561; Sir Robert Cotton, 1570; P. Gassendi, 1592; Gotthold Lessing, 1729; George Lord Byron, London, 1788. Died: George Steevens, editor of Shakespeare, Hampstead, 1800; John F. Blumenbach, physiologist, 1840; Richard Westall, painter, 1850. Feast Days: St. Vincent, martyr at Valencia, 304. St. Anastasius, martyr in Assyria, 628. ST. VINCENTVincent was a Spanish saint, martyred under the proconsul Dacian in the fourth century. The recital of his pious serenity and cheerfulness under unheard-of tortures, is very striking. After having been cruelly broiled over a fire, he was put into a dungeon, bound in stocks, and left without provisions. 'But God,' says Butler, 'sent his angels to comfort him, with whom he sung the praises of his protector. The gaoler, observing through the chinks the prison filled with light, and the saint walking and praising God, was converted upon the spot to the Christian faith, and afterwards baptized.' The bones of the martyr were afterwards kept with the utmost veneration, and Butler speaks of some parts of the body as being still preserved in religious houses in France. ST. VINCENT'S DAYIt is not surprising that a saint with such a history as that of St. Vincent should have made a deep impression on the popular mind, and given rise to superstitious ideas. The ancient remark on his day was couched in somewhat obscure terms: 'Vincenti festo, si sol radiet, memor esto;' merely calling us to remember if the sun shone on that day. The matter was a mystery to modern investigators of folk lore, till a gentle-man residing in Guernsey, looking through some family documents of the sixteenth century, found a scrap of verse expressed in old provincial French: Prens garde an jour St. Vincent, Car, sy ce jour to vois et sent Que le soleil soiet cler et biau, Nous drone du vin plus que l'eau. Not, as might at first sight be supposed, an intimation to bon-vivants, that in that case there would be a greater proportion of wine than of water throughout the year, but a hint to the vine-culturing peasantry that the year would be a dry one, and favourable to the vintage. It will be found that St. Vincent's is not the only day from whose weather that of the future season is prognosticated. FRANCIS BACONOurs is a white-washing age, and, perhaps, to speak in all seriousness, justice and generosity alike do call for the reconsideration of some of the verdicts of the past. Bacon-whose intellectual greatness as the expositor of the inductive philosophy has always been admitted, but whose bribe-receiving as a judge has laid him open to the condemnation of Pope, as 'The wisest, greatest, meanest of mankind' has found a defender in these latter days in Mr. Hepworth Dixon. The great fact which. stares us in the face is, that Bacon, when about to be prosecuted for bribe-receiving by the House of Lords, gave in a paper, in which he used the words: 'I confess that I am guilty of corruption, and do renounce all defence, and put myself upon the grace and mercy of your lordships.' One would think this fact, followed as it duly was by his degradation from the post of Lord Chancellor, enough to appall the most determined white-washer. Nevertheless, Mr. Dixon has come valiantly to the rescue, and really made out a wonderfully good case for his client. His explanations chiefly come to this: the wife of the king's favourite, the Duke of Buckingham, wished to get Bacon's place for a friend of her own; and Coke, a rival and enemy of Bacon, made common cause with her grace. In the loose and bad practice of that ago, when it was customary to give presents even to royalty every new-year's morning, and influence and patronage were sought in all directions by these means, it was not difficult to get up a charge against a chancellor so careless and indifferent to concealment as Bacon. He, taken at a disadvantage under sickness, at first met the twenty-two cases of alleged bribery with an indignant declaration of his innocence of all beyond failing in some instances to inform himself whether the cause was fully at an end before receiving the alleged gift. And it really did, after all, appear that only in three instances was the case still before the court at the time when the gifts were made; and in these there were circumstances fully skewing that no thought of bribery was entertained, nor any of its ordinary results experienced. Bacon, however, was soon made to see that his ruin was determined on, and unavoidable; while by yielding to the assault he might still have hopes from the king's grace. Thus was he brought to make the confession which admitted of a certain degree of guilt; in consequence of which he was expelled the House of Peers, prohibited the court, fined forty thousand pounds, and cast into the Tower. The guilt which he admitted, however, was not that of taking bribes to pervert justice, but that of allowing fees to be paid into his court at irregular times. Mr. Dixon says: 'A series of public acts in which the King and Council concurred, attested the belief in his substantial innocence. By separate and solemn acts he was freed from the Tower; his great fine was remitted; he was allowed to reside in London; he was summoned to take his seat in the House of Lords. Society reversed his sentence even more rapidly than the Crown. When the fight was over, and Lord St. Albans was politically a fallen man, no con-temporary who had any knowledge of affairs ever dreamt of treating him as a convicted rogue. The wise and noble loved him, and courted him more in his adversity than they had done in his days of grandeur. No one assumed that he had lost his virtue because he had lost his place. The good George Herbert held him in his heart of hearts; an affection which Bacon well repaid. John Selden professed for him unmeasurable veneration. Ben Jonson expressed, in speaking of him after he was dead, the opinion of all good scholars, and all honest men: 'My conceit of his person,' says Ben, 'was never increased towards him by his place or honours; but I have and do reverence him for the greatness that was proper only to himself, in that he seemed to me ever by his work one of the greatest of men, and most worthy of admiration that hath been in many ages. In his adversity, I ever prayed that God would give him strength, for greatness he could not want. Neither could I condole in a word or syllable for him, as knowing no accident could do harm to virtue, but rather help to make it manifest.' 'In the dedication of his Essays to the Duke of Buckingham, Bacon uses this expression: 'I do conceive that the Latin volume of them, being in the universal language, may last as long as books last.' The present writer once, at a book-sale, lighted upon a copy of the Essays, which bore the name of Adam Smith as its original owner. It contained a note, in what he presumes to have been the writing of Mr. Smith on this passage, as follows: 'In the preface, what may by some be thought vanity, is only that laudable and innate confidence which any good man and good writer possesses.' SIR ROBERT BRUCE COTTON, AND THE COTTONIAN LIBRARYThe life and labours of this distinguished man present a remarkable instance of the application of the study of antiquities to matters of political importance and public benefit. Descended from an ancient family, he was born at Denton, in Huntingdonshire, and educated at Trinity College, Cambridge. Having settled in London, he there formed a society of learned men attached to antiquarian pursuits, and soon became a diligent collector of records, charters, and other instruments relating to the history of his country; a vast number of which had been dispersed among private hands at the dissolution of the monasteries. In the year 1600, we find Cotton assisting Camden in his Britannia; and in the same year he wrote an Abstract of the question of Precedency between England and Spain, in consequence of Queen Elizabeth having desired the thoughts of the Society already mentioned upon that point. Cotton was knighted by James I, during whose reign he was much consulted by the privy councillors and ministers of state upon difficult points relating to the constitution. He was also employed by King James to vindicate Mary Queen of Scots from the supposed misrepresentations of Buchanan and Thuanus; and he next, by order of the king, examined, with great learning, the question whether the Papists ought, by the laws of the land, to be put to death or to be imprisoned. From his intimacy with Carr, Earl of Somerset, he was suspected by the Court of having some knowledge of the circumstances of Sir Thomas Overbury's death; and he was consequently detained in the custody of an alderman of London for five months, and interdicted the use of his library. He sat in the first parliament of King Charles I, for whose honour and safety he was always zealous. In the following year, a manuscript tract, entitled How a Prince may make himself an absolute Tyrant, being found in Cotton's library, though unknown to him, he was once more parted from his books by way of punishment. These harassing persecutions led to his death, at Cotton House, in Westminster, May 6, 1631. His library, much increased by his son and grandson, was sold to the Crown, with Cotton House (at the west end of Westminster Hall); but in 1712, the mansion falling into decay, the library was removed to Essex House, Strand; thence, in 1730, to Ashburnham House, Westminster, where, by a fire, upwards of 200 of the MSS. were lost, burnt, or defaced; the remainder of the library was removed into the new dormitory of the Westminster School, and, with Major Edwards's bequest of 2000 printed volumes, was transferred to the British Museum. The Cottonian collection originally contained 938 volumes of Charters, Royal Letters, Foreign State Correspondence, and Ancient Registers. It was kept in cases, upon which were the heads of the Twelve Ceasars; above the cases were portraits of the three Cottons, Spelman, Camden, Lambard, Speed, &c., which are now in the British Museum collection of portraits. Besides MSS. the Cottonian collection contained Saxon and English coins, and Roman and English quaties, all now in the British Museum. Camden, Speed, Raleigh, Selden, and Bacon, all drew materials from the Cottonian library; and in our time the histories of England, by Sharon Turner and Lingard, and numerous other works, have proved its treasures unexhausted. THE SOUTH SEA BUBBLEThis day, in the year 1720, inaugurated the most monstrous commercial folly of modern times-the famous South Sea Bubble. In the year 1711, Harley, Earl of Oxford, with the view of restoring public credit, and discharging ten millions of the floating debt, agreed with a company of merchants that they should take the debt upon themselves for a certain time, at the interest of six per cent, to provide for which, amounting to £600,000 per annum, the duties upon certain articles were rendered permanent. At the same time was granted the monopoly of trade to the South Seas, and the merchants were incorporated as the South Sea Company; and so proud was the minister of his scheme, that it was called, by his flatterers, 'the Earl of Oxford's masterpiece.' In 1717, the Company's stock of ten millions was authorized by Parliament to be increased to twelve millions, upon their advancing two millions to Government towards reducing the national debt. The name of the Company was thus kept continually before the public; and though their trade with the South American States was not profitable, they continued to flourish as a monetary corporation. Their stock was in high request; and the directors, deter-mined to fly at high. game, proposed to the Government a scheme for no less an object than the paying off the national debt; this proposition being made just on the explosion in Paris of its counterpart, the Mississippi scheme of the celebrated John Law. The first propounder of the South Sea project was Sir John Blount, who had been bred a scrivener, and was a bold and plausible speculator. The Company agreed to take upon themselves the debt, amounting to £30,981,712, at five per cent. per annum, secured until 1727, when the whole was to become redeemable at the pleasure of the Legislature, and the interest to be reduced to four per cent. Upon the 22nd of January 1720, the House of Commons, in a committee, received the proposal with great favour; the Bank of England was, however, anxious to share in the scheme, but, after some delay, the proposal of the Company was accepted, and leave given to bring in the necessary Bill. At this crisis an infatuation regarding the South Sea speculation began to take possession of the public mind. The Company's stock rose from 130 to 300, and continued to rise while the Bill was in progress. Mr. Walpole was almost the only statesman in the House who denounced the absurdity of the measure, and warned the country of the evils that must ensue; but his admonition was entirely disregarded. Meanwhile, the South Sea directors and their friends, and especially the chairman of the Company, Blount, employed every stratagem to raise the price of the stock. It was rumoured that Spain would, by treaty with England, grant a free trade to all her colonies, and that silver would thus be brought from Potosi, until it would be almost as plentiful as iron; also, that for our cotton and woollen goods the gold mines of Mexico were to be exhausted. The South Sea Company were to become the richest the world ever saw, and each hundred pound of their stock would produce hundreds per annum to the holder. By this means the stock was raised to near 400; it then fluctuated, and settled at 330, when the Bill was passed, though not without opposition. Exchange Alley was the scat of the gambling fever; it was blocked up every day by crowds, as were Cornhill and Lombard-street with carriages. In the words of the ballads of the day: There is a gulf where thousands fell, There all the bold adventurers came; A narrow sound, though deep as hell, 'Change Alley is the dreadful name.' Then stars and garters did appear Among the meaner rabble; To buy and sell, to see and hear The Jews and Gentiles squabble. The greatest ladies thither came, And plied in chariots daily, Or pawned their jewels for a sum To venture in the Alley. On the day the Bill was passed, the shares were at 310; next day they fell to 290. Then it was rumoured that Spain, in exchange for Gibraltar and Port Mahon, would give up places on the coast of Peru; also that she would secure and enlarge the South Sea trade, so that the company might build and charter any number of ships, and pay no percentage to any foreign power. Within five days after the Bill had become law, the directors opened their books for a subscription of a million, at the rate of £300 for every £100 capital; and this first subscription soon exceeded two millions of original stock. In a few days, the stock advanced to 340, and the subscriptions were sold for double the price of the first payment. Then the directors announced a, mid-summer dividend of ten per cent. upon all subscriptions. A second subscription of a million at 400 per cent. was then opened, and in a few hours a million and a half was subscribed for. Meanwhile, innumerable bubble companies started up under the very highest patronage. The Prince of Wales, becoming governor of one company, is said to have cleared £40,000 by his speculations. The Duke of Bridgewater and the Duke of Chandos were among the schemers. By these deceptive projects, which numbered nearly a hundred, one million and a half sterling was won and lost by crafty knaves and covetous fools. The absurdity of the schemes was palpable: the only policy of the projectors was to raise the shares in the market, and then to sell out, leaving the bubble to burst, perhaps, next morning. One of the schemes was 'A company for carrying on an undertaking of great advantage, but nobody to know what it is:' each subscriber, for £2 deposit, to be entitled to £100 per annum per share; of this precious scheme 1000 shares were taken in six hours, and the deposits paid. In all these bubbles, persons of both sexes alike engaged; the men meeting their brokers at taverns and coffee-houses, and the ladies at the shops of milliners and haberdashers; and such was the crowd and confusion in Exchange Alley, that shares in the same bubble were sold, at the same instant, ten per cent. higher at one end of the Alley than at the other. All this time Walpole continued his gloomy warnings, and his fears were impressed upon the Government; when the King, by proclamation, declared all unlawful projects to be public nuisances, and to be prosecuted accordingly, and any broker trafficking in them to be liable to a penalty of £5000. Next, the Lords Justices dismissed all petitions for patents and charters, and dissolved all the bubble companies. Notwithstanding this condemnation, other bubbles sprang up daily, and the infatuation still continued. Attempts were made to ridicule the public out of their folly by caricature and satire. Playing-cards bore caricatures of bubble companies, with warning verses, of which a specimen is annexed, copied from a print called The Bubbler's Medley. In the face of such exposures, the fluctuations of the South Sea stock grew still more alarming. On the 28th of May it was quoted at 550, and in four days it rose to 890. Then came a tremendous rush of holders to sell out; and on June 3rd, so few buyers appeared in the Alley, that stock fell at once from 890 to 640. By various arts of the directors to keep up the price of stock, it finally rose to 1000 per cent. It then became known that Sir John Blount, the chairman, and others, had sold out; and the stock fell throughout the month of August, and on September 2nd it was quoted at 700 only. The alarm now greatly increased. The South Sea Company met in Merchant Taylors' Hall, and endeavoured to appease the unfortunate holders of stock, but in vain: in a few days the price fell to 400. Among the victims was Gay, the poet, who, having had some South Sea stock presented to him, supposed himself to be master of £20,000. At that crisis his friends importuned him to sell, but he rejected the counsel: the profit and principal were lost, and Gay sunk under the calamity, and his life became in danger. The ministers grew more alarmed, the directors were insulted in the streets, and riots were apprehended. Despatches were sent to the king at Hanover, praying his immediate return. Walpole was implored to exercise his influence with the Bank of England, to induce them to relieve the Company by circulating a number of South Sea bonds. To this the Bank reluctantly consented, but the remedy failed: the South Sea stock fell rapidly: a run commenced upon the most eminent goldsmiths and bankers, some of whom, having lent large sums upon South Sea stock, were obliged to abscond. This occasioned a great rim upon the Bank, but the intervention of a holiday gave them time, and they weathered the storm. The South Sea Company were, however, wrecked, and their stock fell ultimately to 150; when the Bank, finding its efforts unavailing to stem the tide of ruin, contrived to evade the loosely-made agreement into which it had partially entered. Public meetings were now held all over England, praying the vengeance of the Legislature upon the South Sea directors, though the nation was as culpable as the Company. The king returned, and parliament met, when Lord Molesworth went so far as to recommend that the people, having no law to punish the directors, should treat them like Roman parricides-tie them in sacks, and throw them into the Thames. Mr. Walpole was more temperate, and proposed inquiry, and a scheme for the restoration of public credit, by engrafting nine millions of South Sea stock into the Bank of England, and the same into the East India Company; and this plan became law. At the same time a Bill was brought in to restrain the South Sea directors, governor, and other officers, from leaving the kingdom for a twelvemonth; and for discovering their estates and effects, and preventing them from transporting or alienating the same. A strange confusion ensued: Mr. Secretary Craggs was accused by Mr. Shippen, 'downright Shippen,' of collusion in the South Sea business, when he promised to explain his conduct, and a committee of inquiry was appointed. The Lords had been as active as the Commons. The Bishop of Rochester likened the scheme to a pestilence; and Lord Stanhope said that every farthing possessed by the criminals, directors or not, ought to be confiscated, to make good the public losses. The cry out-of-doors for justice was equally loud: Mr. Aislabie, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, and Mr. Craggs, were openly accused: five directors, including Mr. Edward Gibbon, the grandfather of the celebrated historian, were ordered to the custody of the Black Rod, and the Chancellor absented himself from parliament until the charge against him had been inquired into. Meanwhile, Knight, the treasurer of the Company, taking with him the books and documents, and secrets of the directors, escaped disguised in a boat on the Thames, and was conveyed thence to Calais, in a vessel hired for the purpose. Two thousand pounds' reward was, by royal proclamation, offered for his apprehension. The doors of the House of Commons were locked, and the keys placed upon the table, and the inquiry proceeded. The South Sea directors and officers were secured; their papers were seized, and such as were Members of Parliament were expelled the House, and taken into custody. Sir John Blount was examined, but little could be drawn from him; and Lord Stanhope, in replying to a reflection made upon him by the Duke of Wharton, spoke with such vehemence that he fell into a fit, and on the next evening expired. Meanwhile, the treasurer of the Company was apprehended near Liege, and lodged in the citadel of Antwerp; but the States of Brabant refused to deliver him up to the British authorities, and ultimately he escaped from the citadel. There is an admirable caricature of this maneuver, entitled 'The Brabant Skreen', in which the Duchess of Kendal, from behind the screen, is supplying Knight with money, to enable him to effect his escape. On the 10th of February, the Committee of Secrecy reported to Parliament the results of their inquiry, shewing how false and fictitious entries had been made in the books, erasures and alterations made, and leaves torn out; and some of the most important books had been destroyed altogether. The properties of many thousands of persons, amounting to many millions of money, had been thus made away with. Fictitious stock had been distributed among members of the Government, by way of bribe, to facilitate the passing of the Bill: to the Earl of Sunderland was assigned £50,000; to the Duchess of Kendal, £10,000; to Mr. Secretary Craggs, £30,000. Mr. Charles Stanhope, one of the Secretaries to the Treasury, had received £250,000, as the difference in the price of some stock, and the account of the Chancellor of the Exchequer she-wed £794,451. He had also advised the Company to make their second subscription a million and a half, instead of a million, without any warrant. In the third subscription his name was down for £70,000; Mr. Craggs, senior, for £659,000; the Earl of Sunderland for £160,000; and C. Stanhope for £47,000. Upon this report, the practices were declared to be corrupt, infamous, and dangerous, and a Bill was brought in for the relief of the unhappy sufferers. In the examination of the accused persons, Charles Stanhope was acquitted by a majority of three only, which caused the greatest discontent through the country. Mr. Chancellor Aislabie was, however, the greatest criminal, and without a dissentient voice he was expelled the House, all his estate seized, and he was committed a close prisoner to the Tower of London. Next day Sir George Caswall, of a firm of jobbers who had been implicated in the business, was expelled the House, committed to the Tower, and ordered to refund £250,000. The Earl of Sunderland was acquitted, lest a verdict of guilty against him should bring a Tory ministry into power; but the country was convinced of his criminality. Mr. Craggs the elder died the day before his examination was to have come on. He left a fortune of a million and a half, which was confiscated for the benefit of the sufferers by the delusion which he had mainly assisted in raising. Every director was mulcted, and two millions and fourteen thousand pounds were confiscated, each. being allowed a small residue to begin the world anew. As the guilt of the directors could not be punished by any known laws of the land, a Bill of Pains and Penalties-a retro-active statute-was passed. The characters of the directors were marked with ignominy, and exorbitant securities were imposed for their appearance. To restore public credit was the object of the next measure. At the end of 1720, the South Sea capital stock amounted to £37,800,000, of which. the allotted stock only amounted to £24,500,000. The remainder, £13,300,000, was the profit of the Company by the national delusion. Upwards of eight millions were divided among the proprietors and subscribers, making a dividend of about £33 6s. 8d. per cent. Upon eleven millions, lent by the Company when prices were unnaturally raised, the borrowers were to pay 10 per cent., and then be free; but it was long before public credit was thoroughly restored. There have been many bubble companies since the South Sea project, but none of such enormity as that national delusion. In 1825, over-speculation led to a general panic; in 1836, abortive schemes had nearly led to results as disastrous; and in 1845, the grand invention of the railway led to a mania which ruined thousands of speculators. But none of these bubbles was countenanced by those to whom the government of the country was entrusted, which was the blackest enormity in the South Sea Bubble.  The powerful genius of Hogarth did not spare the South Sea scheme, as in the emblematic print here engraved, in which a group of persons riding on wooden horses, the devil cutting fortune into collops, and a man broken on the wheel, are the main incidents,-the scene being at the base of a monument of the folly of the age. Beneath are some rhymes, commencing with ' See here the causes why in London So many men are made and undone.' The scene in Exchange Alley has also been excellently painted in our time by Mr. E. M. Ward, R.A., with the motley throng of beaux and ladies turned gamblers, and the accessory pawnbroker's shop, Ina truly Hogarthian spirit. The picture is in the Vernon collection, South Kensington. ANCIENT WIDOWSJanuary 22nd, 1753, died at Broomlands, near Kelso, Jean Countess of Roxburgh, aged 96. No way remarkable in herself, this lady was notable in some external circumstances. She had undergone one of the longest widowhoods of which any record exists-no less than seventy-one years; for her first and only husband, Robert third Earl of Roxburgh, had been lost in the Gloucester frigate, in coming down to Scotland with the Duke of York, on the 7th of May 1682. She must also have been one of the last surviving persons born under the Commonwealth. Her father, the first Marquis of Tweeddale, fought at Long Marston Moor in 1644. Singular as a widowhood of seventy-one years must be esteemed, it is not unexampled, if we are to believe a sepulchral inscription in Camberwell Church, relating to Agnes Skuner, who died in 1499, at the age of 119, having survived her husband Richard Skuner ninety-two years! These instances of long-enduring widowhoods lead us by association of ideas to a noble lady who, besides surviving her husband without second nuptials during a very long time, was further noted. for reaching a much more extraordinary age. Allusion is here made to the celebrated Countess of Desmond, who is usually said to have died early in the seventeenth century, after seeing a hundred and forty years. There has latterly been a disposition to look with doubt on the alleged existence of this venerable person; and the doubt has been strengthened by the discovery that an alleged portrait of her, published by Pennant, proves to be in reality one of Rembrandt's mother. There is, however, very fair evidence that such a person did live, and to a very great age. Bacon, in his Natural History, alludes to her as a person recently in life. 'They tell a tale,' says he, 'of the old Countess of Desmond who lived till she was seven score years old, that she did dentire [produce teeth] twice or thrice; casting her old teeth, and others coming in their place.' Sir Walter Raleigh, moreover, in his History of the World, says: 'I myself knew the old Countess of Desmond, of Inchiquin, in Munster, who lived in the year 1589, and many years since, who was married in Edward the Fourth's time, and held her jointure from all the Earls of Desmond since then; and that this is true all the noblemen and gentlemen in Munster can witness.' Raleigh was in Ireland in 1589, on his homeward voyage from Portugal, and might then form the personal acquaintance of this aged lady. We have another early reference to the Countess from Sir William Temple, who, speaking of cases of longevity, writes as follows: 'The late Robert Earl of Leicester, who was a person of great learning and observation, as well as of truth, told me several stories very extraordinary upon this subject; one of a Countess of Desmond, married out of England in Edward IV's time, and who lived far in King James's reign, and was counted to have died some years above a hundred and forty; at which age she came from Bristol to London, to beg some relief at Court, having long been very poor by reason of the ruin of that Irish family into which she was married.' Several portraits alleged to represent the old Countess of Desmond are in existence: one at Knowle in Kent; another at Bedgebury, near Cranbrook, the seat of A. J. Beresford-Hope, Esq.; and a third in the house of Mr. Herbert at Mucross Abbey, Killarney. On the back of the last is the following inscription: 'Catharine Countesse of Desmonde, as she appeared at ye court of our Sovraigne Lord King James, in this preasent A.D. 1614, and in ye 140th yeare of her age. Thither she came from Bristol to seek relief, ye house of Desmonde having been ruined by Attainder. She was married in the Reigne of King Edward IV, and in y' course of her long Pilgrimage renewed her teeth twice. Her principal residence is at Inchiquin in Munster, whither she undoubtedly proposeth (her purpose accomplished) incontinentlie to return. Laus Deo.'  Another portrait considered to be that of the old Countess of Desmond has long been in the possession of the Knight of Kerry. It was engraved by Grogan, and published in 1806, and a transcript of it appears on this page. The existence of so many pictures of old date, all alleged to represent Lady Desmond, though some doubt may rest on them all, forms at least a corroborative evidence of her existence. It may here be remarked that the inscription on the back of the Mucross portrait is most probably a production, not of her own day, as it pretends to be, but of some later time. On a review of probabilities, with which we need not tire the reader, it seems necessary to conclude that the old Countess died in 1604, and that she never performed the journey in question to London. Most probably, the Earl of Leicester mistook her in that particular for the widow of the forfeited. Garrett Earl of Desmond, of whom we shall presently have to speak. The question as to the existence of the so-called Old Countess of Desmond was fully discussed a few years ago by various writers in the Notes and Queries, and finally subjected to a thorough sifting in an article in the Quarterly Review, evidently the production of one well acquainted with Irish family history. The result was a satisfactory identification of the lady with Katherine Fitzgerald, of the Fitzgeralds of Dromana, in the county of Waterford, the second wife of Thomas twelfth Earl of Desmond, who died at an advanced age in the year 1534. The family which her husband represented was one of immense possessions and influence-able to bring an array of five or six thousand men into the field; but it went to ruin in consequence of the rebel-lion of Garrett the sixteenth Earl in 1579. Although Countess Katherine was not the means of carrying on the line of the family, she continued in her widowhood to draw her jointure from its wealth; did so even after its forfeiture. Thus a state paper dated 1589 enumerates, among the forfeitures of the attainted Garrett, 'the castle and manor of Inchiquin, now in the hands of Katherine Fitz-John, late wife to Thomas, sometyme Earl of Desmond, for terme of lyef as for her dower.' It appears that Raleigh had good reason to know the aged lady, as he received a grant out of the forfeited Desmond property, with the obligation to plant it with English families; and we find him excusing himself for the non-fulfilment of this engagement by saying, There remaynes unto me but an old castle and demayne, which are yet in occupation of the old Countess of Desmond for her jointure.' After all, Raleigh did lease at least two portions of the lands, one to John Cleaver, another to Robert Rove, both in 1589, for rents which were to be of a certain amount 'after the decease of the Lady Cattelyn old Countess Dowager of Desmond, widow,' as the documents shew. Another important contemporary reference to the old Countess is that made by the traveller Fynes Morrison, who was in Ireland from 1599 to 1603, and was, indeed, shipwrecked on the very coast where the aged lady lived. He says in his Itinerary: 'In our time the Countess of Desmond lived to the age of about one hundred and forty years, being able to go on foot four or five miles to the market-town, and using weekly so to do in her last years; and not many years before she died, she had all her teeth renewed.' After hearing on such good authority of her ladyship's walking powers, we may the less boggle at the tradition regarding the manner of her death, which has been preserved by the Earl of Leicester. According to him, the old lady might have drawn on the thread of life somewhat longer than she did, but for an accident. 'She must needs,' says he, 'climb a nut-tree to gather nuts; so, falling down, she hurt her thigh, which brought a fever, and that brought death.' It is plain that, if the Countess was one hundred and forty in 1604, she must have been born in the reign of Edward IV in 1464, and might be married in his reign, which did not terminate till 1483. It might also be that the tradition about the Countess was true, that she had danced at the English Court with the Duke of Gloucester (Richard III), of whom it is said she used to affirm that 'he was the handsomest man in the room except his brother Edward, and was very well made.' |