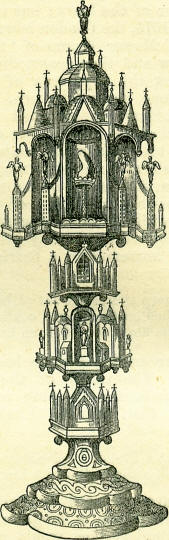

13th JuneBorn: C. J. Agricola, Roman commander, 40, Frejus, in Provence; Madame D'Arblay (nee Frances Burney), English novelist, 1752, Lyme Regis; Dr. Thomas Young, natural philosopher, 1773, Melverton, Somersetshire; Rev. Dr. Thomas Arnold, 1795, Cowes, Isle of Wight. Died: Charles Francis Panard, French dramatist, 1765; Simon Andrew Tissot, eminent Swiss physician, 1797, Lausanne; Richard Lovell Edgeworth, writer on education, 1817, Edgeworthstown, Ireland. Feast Day: St. Anthony of Padua, confessor, 1231; St. Damhnade of Ireland, virgin. ST. ANTHONY OF PADUAFew of the medieval saints adopted into the Romish calendar have attained to such lasting celebrity as St. Anthony, or Antonio, of Padua. All over Italy his memory is held in the highest veneration; but at Padua in particular, where his festival is enthusiastically kept, he is spoken of as Il Santo, or the saint, as if no other was of any importance. Besides larger memoirs of St. Anthony, there are current in the north of Italy small chap-books or tracts describing his character and his miracles. From one of these, purchased within the present year from a stall in Padua, we offer the following as a specimen of the existing folk-lore of Venetian Lombardy. St. Anthony was born at Lisbon on the 15th of August 1195. At twenty-five years of age he entered a convent of Franciscans, and as a preaching friar most zealous in checking heresy, he gained great fame in Italy, which became the scene of his labours. In this great work the power of miracle came to his aid. On one occasion, at Rimini, there was a person who held heretical opinions, and in order to convince him of his error, Anthony caused the fishes in the water to lift up their heads and listen to his discourse.  This miracle, which of course converted the heretic, is represented in a variety of cheap prints, to be seen on almost every stall in Italy, and is the subject of a wood-cut in the chap-book from which we quote, here faithfully represented. On another occasion, to reclaim a heretic, he caused the man's mule, after three days' abstinence from food, to kneel down and venerate the host, instead of rushing to a bundle of hay that was set before it. This miracle was equally efficacious. Then we are told of St. Anthony causing a new-born babe to speak, and tell who was its father; also, of a wonderful miracle he wrought in saving the life of a poor woman's child. The woman had gone to hear St. Anthony preach, leaving her child alone in the house, and during her absence it fell into a pot on the fire; but, strangely enough, instead of finding it scalded to death, the mother found it standing up whole in the boiling cauldron. What with zealous labours and fastings, St. Anthony cut short his days, and died in the odour of sanctity on the 13th of June 1231. Padua, now claiming him as patron saint and protector, set about erecting a grand temple to his memory. This large and handsome church was completed in 1307. It is a gigantic building, in the pointed Lombardo-Venetian style, with several towers and minarets of an Eastern character. The chief object of attraction in the interior is the chapel specially devoted to Il Santo.  It consists of the northern transept, gorgeously decorated with sculptures, bronzes, and gilding. The altar is of white marble, inlaid, resting on the tomb of St. Anthony, which is a sarcophagus of verd antique. Around it, in candelabra and in suspended lamps, lights burn night and day; and at nearly all hours a host of devotees may be seen kneeling in front of the shrine, or standing behind with hands devoutly and imploringly touching the sarcophagus, as if trying to draw succour and consolation from the marble of the tomb. The visitor to this splendid shrine is not less struck with the more than usual quantity of votive offerings suspended on the walls and end of the altar. These consist mainly of small framed sketches in oil or water colours, representing some circumstance that calls for particular thankfulness. St. Anthony of Padua, as appears from these pictures, is a saint ever ready to rescue persons from destructive accidents, such as the over-turning of wagons or carriages, the falling from windows or roofs of houses, the upsetting of boats, and such like; on any of these occurrences a person has only to call vehemently and with faith on St. Anthony in order to be rescued. The hundreds of small pictures we speak of represent these appalling scenes, with a figure of' St. Anthony in the sky interposing to save life and limb. On each are inscribed the letters P. G. R., with the date of the accident;-the letters being an abbreviation of the words Per Grazzia Ricevuto-for grace or favour received. On visiting the shrine, we remarked that many are quite recent; one of them depicting an accident by a railway train. The other chief object of interest in the church is a chapel behind the high altar appropriated as a reliquary. Here, within a splendidly deco-rated cupboard, as it might be called, are treasured up certain relics of the now long deceased saint. The principal relic is the tongue of Il Santo, which. is contained within an elegant case of silver gilt, as here represented. This with other relics is exhibited once a year, at the great festival on the 13th of June, when Padua holds its grandest holiday. It is to be remarked that the article entitled ' St. Anthony and the Pigs,' inserted under January 17, ought properly to have been placed here, as the patronship of animals belongs truly to St. Anthony of Padua, most probably in consequence of his sermon to the fishes. AGRICOLAThe admirable, honest, and impartial biography of Cnæus Julius Agricola, written by the Roman historian Tacitus, who married his daughter, paints him in all the grave, but attractive colours of a noble Roman; assigning to him a valour and virtue, joined to a prudence and skill, which would not have failed to do honour to the best times of the Republic. But Agricola is chiefly interesting to us from his connexion with our own country. His first service was in Britain, under Suetonius Paulinus, the Roman general who finally subdued the rebellious Iceni, under Boadicea, their queen, when 80,000 men are said to have fallen. Agricola afterwards, under the wise reign of Vespasian, was made governor of Britain. He succeeded in destroying the strongholds of North Wales and the Isle of Anglesea, which had resisted all previous efforts, and finally reduced the province to peace; after which he skewed himself at once an enlightened and consummate general, by seeking to civilize the people, by encouraging education, by erecting buildings, by making roads, and by availing himself of all those means which benefit a barbarous country, while they effectually subdue it. When he had in this way established the tranquillity of the province, he proceeded to extend it. Crossing the Tweed, he steadily advanced northwards, the enemy retreating before him. He built a line of forts from the Firth of Forth to the Clyde, and sent the fleet to explore the unknown coast, and to act in concert with his land forces, till at length, having hemmed in the natives on every side, he gained the decisive battle of the Mons Grampius, in which Galgacus so bravely resisted him; after this he retired into the original province, and was recalled by Domitian out of jealousy. Agricola died soon after his return to Rome, in the year 93, in his fifty-fourth year; the circumstances of his death were somewhat peculiar, and Tacitus throws out a hint that he might have been poisoned. FANATICISM ANALYZED BY ARNOLDArnold regarded fanaticism as a form of selfishness. 'There is an ascending scale,' said he, 'from the grossest personal selfishness, such as that of Cæsar or Napoleon, to party selfishness, such as that of Sylla, or fanatical selfishness, that is the idolatry of an idea or principle, such as that of Robespierre or Dominic, and some of the Covenanters. In all of these, excepting perhaps the first, we feel a sympathy more or less, because there is something of personal self-devotion and sincerity; but fanaticism is idolatry, and it has the moral evil of idolatry in it; that is, a fanatic worships something which is the creature of his own devices, and thus even his self-devotion in support of it is only an apparent self-sacrifice, for it is in fact making the parts of his nature or his mind which he least values offer sacrifice to that which he most values.' On another occasion he said: The life and character of Robespierre has to me a most important lesson; it shows the frightful consequences of making everything give way to a favourite notion. The man was a just man, and humane naturally, but he would narrow everything to meet his own views, and nothing could check him at last. It is a most solemn warning to us, of what fanaticism may lead to in God's world. It is a pity that Arnold did not take us on from personal to what may be called class or institutional fanaticism, for it is a principle which may affect any number of men. We should have been glad to see from his pen an analysis of that spirit under which a collective body of men will grasp, deny justice, act falsely and cruelly, all for the good of the institution which they represent, while quite incapable of any such procedure on their own several accounts. Here, too, acting for an idea, there is an apparent exemption from selfishness; but an Arnold could have shown how something personal is, after all, generally involved in such kinds of procedure; the more dangerous, indeed, as well as troublesome, that it can put on so plausible a disguise. There are even such things as fanaticisms upon a national scale, though these are necessarily of rarer occurrence; and then do we see a whole people propelled on to prodigious exterminating wars, in which they madly ruin, and are ruined, while other nations look on in horror and dismay. In these cases, civilization and religion afford no check or alleviation of the calamity: the one only gives greater means of destruction; the other, as usual, blesses all banners alike. The sacred name of patriotism serves equally in attack and defence, being only a mask to the selfish feelings actually concerned. All such things are, in fact, IDOLATRIES-the worship of something which is 'the creature of our own devices,' to the entire slighting and putting aside of those principles of justice and kindness towards others which God has established as the only true guides of human conduct. |