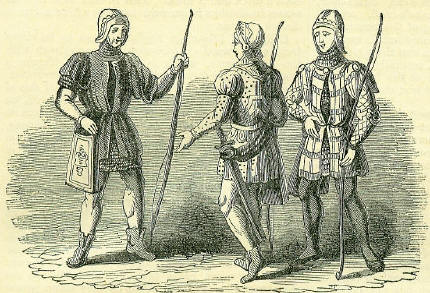

12th JuneBorn: Rev. Charles Kingsley, novelist, 1819; Harriet Martineau, novelist, historian, miscellaneous writer, 1802. Died: James III of Scotland, killed near Bannockburn, Stirlingshire, 1488; Adrian Turnebus, eminent French scholar, 1565, Paris; James, Duke of Berwick, French commander, 1734, Philipsburgh; William Collins, poet, 1759, Chichester; R. F. P. Brunck, eminent philologist, 1803; General Pierre Augereau (Duc de Castiglioni), 1816; Edward Troughton, astronomical instrument maker, 1835, London; Rev. Dr. Thomas Arnold, miscellaneous writer, eminent teacher, 1842, Rugby; Rev. John Hodgson, author of History of Northumberland, 1845; Dr. Robert Brown, eminent botanist, 1858. Feast Day: Saints Basilides, Quirinus, or Cyrinus, Nabor, and Nazarius, martyrs; St. Onuphrius, hermit; St. Ternan, Bishop of the Picts, confessor, 5th century; St. Eskill, of Sweden, bishop and martyr, 11th century; St. John of Sahagun, confessor, 1479. COLLINSThe story of the life of Collins is a very sad one: Dr. Johnson, in his Lives of the Poets, well expresses the unhappy tenor of it. 'Collins,' he says, 'who, while he studied to live, felt no evil but poverty, no sooner lived to study than his life was assailed by more dreadful calamities, disease and insanity.' The poet's father, a hatter and influential man in Chichester, procured his son a good education, first at Winchester school, and then at Oxford. Accordingly, Collins promised well: but the seeds of disease, sown already, though yet concealed, silently took root; and strange vacillation and indecision trailed in the path of a mind otherwise well fitted for accomplishing noble designs. Suddenly and unaccountably throwing up his advantages and position at Oxford, he proceeded to London as a literary adventurer. His was not the strong nature to breast so rough a sea; and when home-supplies, for some reason, at length failed, he was speedily reduced to poverty. Nevertheless, at the age of twenty-six, an opportune legacy removed for ever this trouble; and then it seemed he was about to enter upon a brighter existence. Then it was that the most terrible of all personal calamities began to assail him. Every remedy, hopeful or hopeless, was tried. He left off study entirely; he took to drinking; he travelled in France; he resided in an asylum at Chelsea; he put himself under the care of his sister in his native city. All was in vain; he died, when not quite forty, regretted and pitied by many kind friends. As we may naturally suppose, Collins wrote but little. At school he produced his Oriental Eclogues, and published them when at college, in 1742, some four or five years afterwards. These poems he grew to despise, and fretted at the public, because it continued to read them. In 174,6 he published his Odes, when the public again crossed him; but this time by not reading what he had written. He was so annoyed that he burnt all the remaining copies. One lost poem, of some length, entitled an Ode on the Popular Superstitions of the Highlands of Scotland, was recovered and published in 1788. Time has avenged the neglect which Collins experienced in his own day. His Ode on the Passions is universally admired; the Ode to Evening is a masterpiece; there are not two more popular stanzas to be found than those which commence 'How sleep the brave;' nor a sweeter verse in all the language of friend: ship than that in the dirge for his poet-friend Remembrance oft shall haunt the shore When Thames in summer wreaths is dressed; And oft suspend the dashing oar To bid his gentle spirit rest. ROBERT BROWNA kind, modest, great man-so early in the history of science, that he may be called the originator of vegetable physiology; so late in the actual chronology of the world that he died on the 12th of June 1858 (at, it is true, the advanced age of eighty-five)-has to be described under this homely appellative. His gentle, yet dignified presence in his department of the British Museum will long be a pleasing image in the memory of living men of science. The son of a minister of the depressed episcopal church of Scotland at Montrose, he entered life as an army surgeon, but quickly gravitated to his right place; first acting as naturalist in an Australian surveying expedition; afterwards as keeper of the natural history collections of Sir Joseph Banks; finally, as keeper of the botanical collection in the National Museum. His great work was the Botany of New Holland, published in 1814; but he wrote many papers, equally valuable in point of matter, for the Linnaean and Royal Societies. What was a dry assemblage of facts under an utterly wrong classification before his time, became through his labours a clearly apprehensible portion of the great scheme of nature. The microscope was the grand means by which this end was carried out-an instrument little thought of before his day, but which, through his example in botany, was soon after introduced in the examination of the animal kingdom, with the noblest results. Indeed, it may be said that, whereas little more than the externals of plants and animals were formerly cared for, we now have become familiar with their internal constitution, their growth and development, and their several true places in nature, and for this, primarily, we must thank Mr. Robert Brown. PLANTS NAMED AFTER ANIMALSA great number of plants are recognised, popularly at least, by names involving reference to some animal, or what appears as such. Sometimes this animal element in the name is manifestly appropriate to something in the character of the plant; but often it is so utterly irrelative to anything in the plant itself, its locality, and uses, that we are forced to look for other reasons for its being applied. According to an ingenious correspondent, it will generally be found that in these latter cases the animal name is a corruption of some early term having a totally different signification. Our correspondent readily admits that cats love cat-mint, that the bee-orchis and the fly-orchis resemble respectively the bee and the fly, and that the flower of the single columbine is like an assemblage of doves [Lat. columba, a dove,]; hence the animal names are here presumably real. He allows that the crane's-bill, the stork's-bill, fox-tail grass, hare's-tail grass, adder's-tongue fern, hare's-ear, lark's-spur, mare's-tail, mouse-tail, and snake's-head, are all appropriate on the plain meaning of the terms. He goes on, however, to cite a more considerable number, regarding which he holds it certain that the appellative is a metamorphose of some word, generally in another language, with no meaning such as the term would suggest to ordinary ears. We let him state his ideas in his own way: The name hare-bell is at present assigned to the wild hyacinth (Scala Nutans), but properly belonging to the blue-bell (Campanula rotundifolia). Harebell may be traced to the Welsh awyr-bel, a balloon; that is, an inflated ball or distended globe or bell, to which description this flower corresponds; the name there-fore would be more correctly spelled ' Airbell.' Fox-glove, embodying the entire sense of the Latin Digitalis purpurea, is simply the red-glove, or red-gauntlet, for fox or foxy, as the Latin fuscus, and Italian fosco, signifies tawny or red, and hence is derived the name of the fox himself. The toad-flax (Cymbalaria Italica) is so named from the appearance it presents of a multitudinous mass of threads (flax), matted together in a cluster or branch, for which our old language had the significant term tod, which may be met with in several of our older dictionaries, from tot, or total, a mass or assemblage of things. So the toad-pipe (Equisetum Arvense), which consists of a cluster of jointed hair-like tubes, as also the bastard-toadflax, a plant with many clustering stems, both have the term toad or tod applied to them for the same reason. Louse-wort (Pedicularis palustris) appears to be only a corruption of loose-wort, the plant being otherwise called the red-rattle, from. its near re-semblance to the yellow-rattle (Rhinanthus), the seeds of which, being loosely held in a spacious inflated capsule, may be distinctly heard to rattle when the ripe, dry seed-vessel is shaken. Buck-bean (Menyanthes trifoliata) is more correctly bog-bean, its habitat being in very wet bog land. Swallow-wort, otherwise celandine (Chaelidonium, Majus), is properly sallow-wort, having received this name from the dark yellow juice which exudes freely from its stems and roots when they are broken. Horse-radish takes its name from its excessive pungency, horse, as thus used, being derived- from the old English curs, or Welsh gwres, signifying hot or fierce; and the horse-chestnut, not from any relation to a chestnut horse, but for a like reason, namely, that it is hot or bitter, and therein differs from the sweet or edible chestnut. The horse-mint also is pungent and disagreeable to the taste and to the smell; as compared with the cultivated kinds of mint. Bear's garlic or the common wild garlic (Allium ursinum), may be traced in the Latin specific name, ursinum, and this, although it would at the pre-scut time be interpreted as 'pertaining to a bear,' may have had what is termed a barbarous origin, viz., curs-inon or urs-inon, the hot or strong onion. The bear gets his own name, Ursa, from the same original, as describing his savage ferocity. The sow-thistle, which is not indeed a true thistle, has the latter part of its name from the thistle-like appearance of its leaves; when these are handled, however, they are found to be perfectly inoffensive-they are formidable to the eye only, being too soft to inflict the slightest puncture; hence sote or sooth-thistle, that is soft thistle. The duck-weed, or ducks-meat, is by no means choice food for ducks, but simply ditchweed. It is that minute, round, leaf-like plant which so densely covers old moats and ponds with a green mantle. Its Latin name, Lemna, confirms this, derived as it is from the Greek Limne, a stagnant pool. Thecorruption in this case may have originated in a misconstruction of the Saxon word Dig, which signifies both a ditch and a duck. This is still used in both senses in districts in our own country where a Saxon dialect prevails. Colts'-foot (Tussilago fasfara) seems to be either from cough-wood or cold-wood, in accordance with the Latin name, which is derived from Tussis, a cough. We are disposed to regard it as a corruption, and to conclude that it refers to the medicinal use of the plant, because, in our English species at least, we see no resemblance to the foot of a horse, whereas its virtue in the cure of colds, coughs, and hoarseness, has, whether justly or not, been believed in from time immemorial. Pliny tells us that it had been in use from remote times, even at his day, the fume of the burning weed being inhaled through a reed. Lastly maybe instanced the well-known gooseberry, notable for two things of very opposite character-for its fruit and its thorns,-the latter hardly less dreaded than the former is coveted, and in the name given to this tree may be found a combined reference to these two features-its terrors and its attractions. In the Italian, Uva spina, this is very plainly shown. The old English name carberry, probably has the same meaning; and the north country name, grozar or groser, as also the French groseille, and the Latin grossularia, scarcely conceal in their slightly inverted form the original gorse, which means prickly. In short, we regard the name gooseberry as simply a modified form of gorseberry. There was a time when goose was both written and pronounced gos, as is shown by the still current word gosling, a young goose, and gorse (the furze or whin) is familiarly pronounced exactly in the same way; therefore the transition of gorse to goose will not be wondered at. ARCHERY IN ENGLANDIn an epistle to the sheriffs of London, dated 12th June 1349, Edward III sets forth how 'the people of our realm, as well of good quality as mean, have commonly in their sports before these times exercised their skill of shooting arrows; whence it is well known that honour and profit have accrued to our whole realm, and to us, by the help of God, no small assistance in our warlike acts.' Now, however, 'the said skill being as it were wholly laid aside,' the king proceeds to command the sheriffs to make public proclamation that 'every one of the said city, strong in body, at leisure times on holidays, use in their recreations bows and arrows, or pellets or bolts, and learn and exercise the art of shooting, forbidding all and singular on our behalf, that they do not after any manner apply themselves to the throwing of stones, wood, or iron, handball, football, bandyball, cambuck, or cockfighting, nor suchlike vain plays, which have no profit in them.'  It is not surprising that the king was thus anxious to keep alive archery, for from the Conquest, when it proved so important at Hastings, it had borne a distinguished part in the national military history. Even in his own time, notwithstanding the king's complaint of its decay, it was (to use modern language) an arm of the greatest potency. Crecy, Poitiers, and Agincourt were, in fact, archers' victories. At Homildon, the men-at-arms merely looked on while the chivalry of Scotland fell before the clothyard shafts. In one skirmish in the French wars, eighty bowmen defeated two hundred French knights; and in another a hundred and twenty were disposed of by a sixth of their number. There is a well-known act of the Scottish parliament, in the reign of James I, expressive of the eagerness of the rulers of that nation to bring them up to a par with the English in this respect. In the reign of Edward IV, it was enacted that every Englishman, whatever his station, the clergy and judges alone excepted, should own a bow his own height, and keep it always ready for use, and also provide for his sons' practising the art from the age of seven. Butts were ordered to be erected in every township, where the inhabitants were to shoot 'up and down,' every Sunday and feast day, under penalty of one halfpenny. In one of his plain-speaking sermons, Latimer censured the degeneration of his time in respect to archery. 'In my time my poor father was as delighted to teach Inc to shoot as to learn any other thing; and so, I think, other men did their children; he taught me how to draw, how to lay my body and my bow, and not to draw with strength of arm as other nations do, but with strength of body. I had my bow bought me according to my age and strength; as I increased in them, so my bows were made bigger and bigger; for men shall never shoot well, except they be brought up to it. It is a goodly art, a wholesome kind of exercise, and much commended as physic.' From this time the art began to decline. Henry VII found it necessary to forbid the use of the cross-bow, which was growing into favour, and threatening to supersede its old conqueror, and his successor fined the possessor of the former weapon ten pounds. Henry VIII was himself fond of the exercise, and his brother Arthur was famed for his skill, so that archers did not lack encouragement. 'On the May-day then next following, the second year of his reign,' says Holinshed, 'his grace being young, and willing not to be idle, rose in the morning very early, to fetch May, or green boughs; himself fresh and richly appareled and clothed, all his knights, squires, and gentlemen in white satin, and all his guard and yeomen of the crown in white sarcenet; and so went every man with his bow and arrows shooting to the wood, and so returning again to the court, every man with a green bough in his cap. Now at his returning, many hearing of his going a Maying, were desirous to see him shoot, for at that time his grace shot as strong and as great a length as any of his guard. There came to his grace a certain man with bow and arrows, and desired his grace to take the muster of him, and to see him shoot; for at that time his grace was contented. The man put then one foot in his bosom, and so did shoot, and shot a very good shot, and well towards his mark; whereof not only his grace, but all others greatly marvelled. So the king gave him a reward for his so doing, which person after of the people and of those in the court was called, Foot-in-Bosom.' Henry conferred on Barlow, one of his guard, the jocular title of Duke of Shoreditch, as an acknowledgment of his skill with the bow, a title long afterwards held by the principal marksman of the city. In 1544 the learned Ascham took up his pen in the cause of the bow, and to counsel the gentlemen and yeomen of England not to change it for any other weapon, and bravely does he in his Toxophilus defend the ancient arm, and show 'how fit shooting is for all kinds of men; how honest a pastime for the mind; how wholesome an exercise for the body; not vile for great men to use, nor costly for poor men to sustain; not lurking in holes and corners for ill men at their pleasure to misuse it, but abiding in the open sight and face of the world, for good men if at fault, by their wisdom to correct it.' He attributes the falling-off in the skill of Englishmen to their practising at measured distances, instead of shooting at casual marks, or changing the distance at every shot. On the 17th of September 1583, there was a grand muster of London archers. Three thousand of them (of whom 942 wore gold chains), attended by bellmen, footmen, and pages, and led by the Duke of Shoreditch, and the Marquises of CIerkenwell, Islington, Shacklewell, Hoxton, and St. John's Wood, marched through the city (taking up the city dignitaries on the route) to Hoxton Fields, where a grand shooting match took place, the victors in the contest being carried home by torchlight to a banquet at the Bishop of London's palace. Charles I, himself skilled in the use of the long bow, appointed two special commissions to enforce the practice of archery; but with the civil war the art died out; in that terrible struggle the weapon that had won so many fields took no part, except it might be to a small extent in the guerilla warfare carried on against Cromwell in the Scottish Highlands. Charles II had his keeper of the bows; but the office was a sinecure. In 1675, the London bowmen assembled in honour of Mayor Viners of 't'other Bottle' fame, and now and then spasmodic efforts were made to renew the popularity of the sport, but its day had gone, never to return. In war, hoblers, or mounted archers, were employed to disperse small bodies of troops, and frustrate any attempts of the beaten foe to rally. The regular bowmen were drawn upon a 'hearse,' by which the men were brought as near the enemy as possible, the front of the formation being broad, while its sides tapered gradually to the rear. They were generally protected against the charge of horsemen by a barrier of pikes, or in default: Sharp stakes cut out of hedges They pitched on the ground confusedly, To keep the horsemen off from breaking in. Each archer carried sixteen heavy and eight light shafts. The range of the former was about 240 yards, for Drayton records, as an extraordinary feat, that an English archer at Agincourt: Shooting at a French twelve score away, Quite through the body stuck him to a tree. The lighter arrows, used to gall the enemy, would of course have a longer range. Neade says an old English bow would carry from 18 to 20 score yards, but this seems rather too liberal an estimate. Shakspeare says: A good archer would clap in the clout at twelve score, and carry a forehand shaft a fourteen and a fourteen and a half. The ballad mongers make Robin Hood and Little John shoot a measured mile, and give the father of the Sherwood outlaw credit for having sent an arrow two north country miles and an inch at a shot! Wych, hazel, ash, and elm were used for ordinary bows, but war-bows were always made of yew. The prices were usually fixed by statute. In Elizabeth's reign they were as follows:-Best foreign yew 6s. 8d.; second best, 3s. 4d.; English yew, and 'livery' bows (of coarsest foreign yew) 2s. Bows were rubbed with wax, resin, and tallow, and covered with waxed cloth, to resist the effects of damp, heat, and frost. Each bow was supplied with three good hempen strings, well whipped with fine thread. The length of a bow was regulated by the height of the archer, the rule being that it should exceed his stature by the length of his foot. The arrows used at Agincourt were a yard long without the head, but the usual length was from twenty-seven to thirty-three inches. They were made of many woods,-hazel, turkeywood, fustic, alder, beech, black-thorn, elder, sallow; the best being of birch, oak, ash, service-tree, and hornbeam. The grey goose feather was considered the best for winging them, and the various counties were laid under contribution for a supply of feathers whenever war was impending. The ancient weapon of England has degenerated into a plaything; but in the Volunteer movement we have a revival of the spirit which made the long-bow so formidable in the 'happy hitting hands' of our ancestors; and we may say of the rifle as Ascham said of the bow, 'Youth should use it for the most honest pastime in peace, that men might handle it as a most sure weapon in war.' |