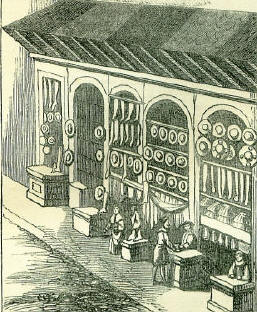

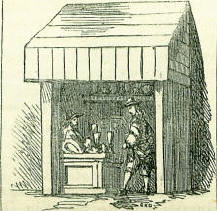

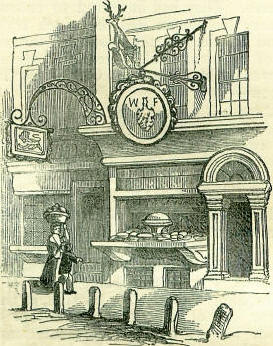

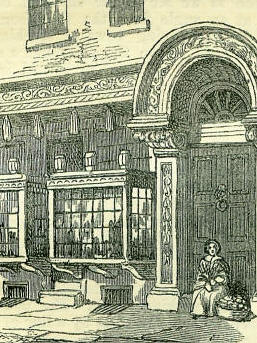

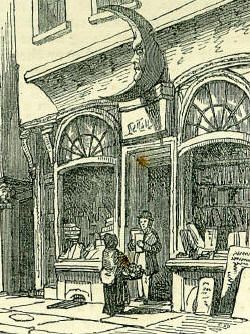

9th MarchBorn: Lewis Gonzaga (St Aloysius), 1568; Dr. Joseph Franz Gall, founder of phrenology, 1757, Tiefenbrunn, Suabia; William Cobbett, political writer, 1762, Farnham. Died: Sultan Bajazet I, Antioch; David Rizzio, 1566, murdered, Holyrood; William Warner, poet, 1609, Amwell; Francis Beaumont, dramatist, 1616; Cardinal Jules Mazarine, 1661, Vincennes; Bishop Joseph Wilcocks, 1756; John Calas, broken on the wheel, 1762, Toulouse; William Guthrie, historical and geographical writer, 1771, London; Dr. Samuel Jebb, 1772, Derbyshire; Dr. Edward Daniel Clarke, traveller, 1822, Pall Mall; Anna Letitia Barbauld, writer of books for the young, 1825, Stoke Newington; Miss Linwood, artist in needlework, 1845; Professor Oersted, Danish natural philosopher, 1851. Feast Day: St. Pacian, Bishop of Barcelona, 4th century. St. Gregory, of Nyssa, bishop, 400. St. Frances, widow, of Rome, foundress of the Collatines, 1440. St. Catherine, of Bologna, virgin, 1463. WILLIAM COBBETT Were we asked to name the Englishman who most nearly answers to the typical John Bull which Leech delights to draw in Punch, we should pause between William Hogarth and William Cobbett, and likely say-Cobbett. His bluff speech, his hearty and unreasonable likes and dislikes, his hatred of craft and injustice, his tenderness, his roughness, his swift anger and gruff pity, his pugnacity, his pride, his broad assurance that his ways are the only right ways, his contempt for abstractions, his exaltation of the solidities over the elegancies of life, these and a score of other characteristics identify William Cobbett with John Bull. Cobbett was, in his origin, purely an English peasant. He was born in a cottage-like dwelling on the south side of the village of Farnham, in Surrey. Since the Cobbetts left it, about 1780, it has been used as a public-house under the name of the 'Jolly Farmer,'-noted, as we understand, for its home-brewed ale and beer, the produce of the Farnham hops. Behind it is a little garden and steep sand-rock, to which Cobbett makes allusion in his writings. 'From my infancy,' says he,-'from the age of six years, when I climbed up the side of a steep sand-rock, and there scooped me out a plot of four feet square to make me a garden, and the soil for which I carried up in the bosom of my little blue smock frock (a hunting shirt), I have never lost one particle of my passion for these healthy and rational, and heart-charming pursuits.' Cobbett, having a hard-working, frugal man for his father, was allowed no leisure and little education in his boyhood. I do not remember,' he says, 'the time when I did not earn my own living. My first occupation was driving the small birds from the turnip-seed, and the rooks from the pease. When I first trudged a-field, with my wooden bottle and my satchel slung over my shoulders, I was hardly able to climb the gates and stiles; and at the close of the day, to reach home was a task of infinite difficulty. My next employment was weeding wheat, and leading a single horse at harrowing barley. Hoeing pease followed; and hence I arrived at the honour of joining the reapers in harvest, driving the team, and holding the plough. We were all of us strong and laborious; and my father used to boast, that he had four boys, the eldest of whom was but fifteen years old, who did as much work as any three men in the parish of Farnham. Honest pride and happy days! The father, nevertheless, contrived, by his own exertions in the evening, to teach his sons to read and write. The subject of this memoir in time advanced to a place in the garden of Waverley Abbey, afterwards to one in Kew Garden, where George III took some notice of him, and where he would lie reading Swift's Tale of a Tab in the evening light. In 1780, he went to Chatham and enlisted as a foot-soldier, and immediately after his regiment was shipped off to Nova Scotia, and thence moved to New Brunswick. He was not long in the army ere he was promoted over the heads of thirty sergeants to the rank of sergeant-major, and without exciting any envy. His steadiness and his usefulness were so marked, that all the men recognised it as a mere matter of course that Cobbett should be set over them. He helped to keep the accounts of the regiment, for which he got extra pay. He rose at four every morning, and was a marvel of order and industry. 'Never,' he writes, 'did any man or thing wait one moment for me. If I had to mount guard at ten, I was ready at nine.' His leisure he diligently applied to study. He learnt grammar when his pay was sixpence a-day. 'The edge of my berth, or that of my guard-bed,' he tells us, 'was my seat to study in; my knapsack was my book-case; a bit of board lying on my lap was my writing table. I had no money to buy candle or oil; in winter time it was rarely I could get any light but that of the fire, and only my turn even of that. To buy a pen, or a sheet of paper, I was compelled to forego some portion of food, though in a state of half starvation. I had no moment to call my own, and I had to read and write amidst the talking, laughing, singing, whistling, and brawling of at least half a score of the most thoughtless men.' That was at the outset, for he soon rose above these miseries, and began to save money. While in New Brunswick he met the girl who became his wife. He first saw her in company for about an hour one evening. Shortly afterwards, in the dead of winter, when the snow lay several feet thick on the ground, he chanced in his walk at break of day to pass the house of her parents. It was hardly light, but there was she out in the cold, scrubbing a washing tub. That action made her mistress of Cobbett's heart for ever. No sooner was he out of hearing, than he exclaimed, 'That's the girl for me!' She was the daughter of a sergeant of artillery, and then only thirteen. To his intense chagrin, the artillery was ordered to England, and she had to go with her father. Cobbett by this time had managed to save 150 guineas, the produce of extra work. Considering that Woolwich, to which his sweetheart was bound, was a gay place, and that she there might find many suitors, who, moved by her beauty, might tempt her by their wealth, and, unwilling that she should hurt herself with hard work, he sent her all his precious guineas, and prayed that she would use them freely, for he could get plenty more; to buy good clothes, and live in pleasant lodgings, and be as happy as she could until he was able to join her. Four long years elapsed before they met. Cobbett, when he reached England, found her a maid-of-all-work, at £5 a-year. On their meeting, without saying a word about it, she placed in his hands his parcel of 150 guineas unbroken. He obtained his discharge from the army, and married the brave and thrifty woman. She made him an admirable wife; never was he tired of speaking her praises, and whatever comfort and success he afterwards enjoyed, it was his delight to ascribe to her care and to her inspiration. At this time he brought a charge of peculation against four officers of the regiment to which he had belonged. A court-martial was assembled, witnesses were summoned, but Cobbett was not forthcoming. He had fled to France, and for his conduct no fair explanation was ever given. From France he sailed to New York in 1792, and settled in Philadelphia. Shunned and persecuted in England, Dr. Priestley sought a home in Pennsylvania in 1791, Cobbett attacked him in 'Observations on the Emigration of a Martyr to the Cause of Liberte, by Peter Porcupine.' The pamphlet took amazingly, and Cobbett followed it up with a long series of others discussing public affairs in a violent anti-democratic strain. He drew upon himself several prosecutions for libel, and to escape the penalties he returned to England in 1800, and tried to establish The Porcupine, a daily Tory newspaper, in London. It failed after running a few months, and then he started his famous Weekly Register, which he continued without interruption for upwards of thirty-three years. The Register at first advocated Toryism, but it soon veered round to that Radicalism with which its name became synonymous. The unbridled invective in which Cobbett indulged kept actions for libel continually buzzing about his cars. The most serious of these occurred in 1810, and resulted in his imprisonment for two years and a fine of £1,000 to the King. In 1817, he revisited America, posting copy regularly for his Register; and he returned in 1819, bearing with him the bones of Thomas Paine. Again he tried a daily newspaper in London, but he was only able to keep it going for two months. He wished to get into Parliament, and unsuccessfully contested Coventry in 1820, and Preston in 1826; but in 1832 he was returned for Oldham. His parliamentary career was comparatively a failure. He was too precipitate and dogmatic for that arena. The late hours sapped his health, and he died after a short illness, on the 18th of June 1835, aged seventy-three. The Weekly Register, whilst it alone might stand for the sole business of an ordinary life, represented merely a fraction of Cobbett's activity. He farmed, he travelled, he saw much society, and wrote books and pamphlets innumerable. His Register was denounced as 'two-penny trash.' He thereon issued a series of political papers entitled Two penny Trash, which sold by the hundred thousand. His industry, early rising, and methodical habits enabled him to get through an amount of work incredible to ordinary men. He wrote easily, but spared no pains to write well; his terse, fluent, and forcible style has won the praise of the best critics. He had no abstruse thoughts to communicate; he knew what he wanted to say, and had the art of saying it in words which anybody who could read might comprehend. Few could match him at hard hitting in plain words, or in the manufacture of graphic nick-names. Dearly did. he enjoy fighting, and a plague, a terror, and a horror he was to many of his adversaries. Jeremy Bentham said of him: 'He is a man filled with odium kumani generis. His malevolence and lying are beyond anything.' Many others spoke of him with equal bitterness, but years have toned off these animosities, and the perusal of his fiercest sayings now only excites amusement. Cobbett's character is at last understood as it could scarcely be in the midst of the passions which his wild words provoked. It is clearly seen that his understanding was wholly subordinate to his feelings; that his feelings were of enormous strength; and that his understanding, though of great capacity, had a very limited range. His feelings were kindly, and they were firmly interwoven with the poor and hard-working people of England. Whatever men or measures Cobbett thought likely to give Englishmen plenty of meat and drink, good raiment and lodging, he praised; and whatever did not directly offer these blessings he denounced as impostures. Doctrine more than this he had not, and would hear of none. Thus it was that he came to ridicule all arts and studies which did not bear on their face the promise of physical comfort. Shakespeare, Milton, the British Museum, Antiquaries, Philanthropists, and Political Economists, all served in turn as butts for the arrows of his contempt. Of the craft of the demagogue he had little; he made enemies in the most wanton and impolitic manner; and thoughts of self-interest seldom barred for an instant the outflow of his feelings. Fickle and inconsistent as were those feelings, intellectually considered, in them Cobbett wrote himself out at large. From his multitudinous and diffuse writings a most entertaining volume of readings might be selected. His love of rural life and rural scenes is expressed in many bits of composition which a poet might envy; and his trenchant criticisms of public men and affairs, and his grotesque opinions, whilst they would prove what power can live in simple English words, would give the truest picture of him who holds high rank among the great forces which agitated England in the years anterior to the Reform Bill. DEATH OF CARDINAL MAZARINMazarin, an Italian by birth, and a pupil of Richelieu, but inferior to his master, was the minister of the Regency during the minority of Louis XIV. He was more successful at the close of his career in his treaties of peace than he had been in his wars and former negotiations. In February 1661, he had concluded at Vincennes a third and last treaty with Charles, duke of Lorraine, by which Strasburg, Phalsburg, Stenai, and other places were given up to France. A fatal malady had seized on the Cardinal whilst engaged in the conferences of the treaty, and, worn by mental agony, he brought it home with him to the Louvre. He consulted Grenaud, the great physician, who told him that he had two months to live. This sad assurance troubled the Cardinal greatly; his pecuniary wealth, his valuables and pictures, were immense. He was fond of hoarding, and his love of pictures was as strong as his love of power-perhaps even stronger. Soon after his physician had told him how short a time he had to live, Brienne perceived the Cardinal in night-cap and dressing-gown tottering along his gallery, pointing to his pictures, and exclaiming, 'Must I quit all these?' He saw Brienne, and seized him: 'Look!' he exclaimed, 'look at that Correggio! this Venus of Titian! that incomparable Deluge of Caracci! Ah! my friend, I must quit all these! Farewell, clear pictures, that I loved so dearly, and that cost me so much!' His friend surprised him slumbering in his chair at another time, murmuring, 'Grenaud has said it! Grenaud has said it!' A few days before his death, he caused himself to be dressed, shaved, rouged, and painted, 'so that he never looked so fresh and vermilion' in his life. In this state he was carried in his chair to the promenade, where his envious courtiers cruelly rallied him with ironical compliments on his appearance. Cards were the amusement of his death-bed, his hand being hold by others; and they were only interrupted by the visit of the Papal Nuncio, who came to give the Cardinal that plenary indulgence to which the prelates of the Sacred College are officially entitled. MRS. BARBAULDAnna Letitia Aiken, by marriage Mrs. Barbauld, spent most of her long life of eighty-two years in the business of teaching and in writing for the young. Of dissenting parentage and connexions, and liberal tendencies of mind, she was qualified to confer honour on any denomination or sect she might belong to by her consummate worth, amiableness, and judgment. She was at all times an active writer, and her writings both in prose and verse display many admirable qualities; nevertheless, the public now knows little about them, her name being chiefly kept in remembrance by her contributions to the well-known children's book, mainly of her brother's composition, the Evenings at Home. Amongst Mrs. Barbauld's miscellaneous pieces, there is an essay Against Inconsistency in our Expectations, which has had the singular honour of being reprinted for private distribution by more than one person, on account of its remarkable lessons of wisdom which it is calculated to convey. She starts with the idea that 'most of the unhappiness of the world arises rather from disappointed desires than from positive evil.' It becomes consequently of the first importance to know the laws of nature, both in matter and in mind, that we may reach to equity and moderation in our claims upon Providence. 'Men of merit and integrity,' she remarks, 'often censure the dispositions of Providence for suffering characters they despise to run away with advantages which, they yet know, are purchased by such means as a high and noble spirit could never submit to. If you refuse to pay the price, why expect the purchase?' This may be called the keynote of the whole piece. Say that a man has set his heart on being rich. Well, by patient toil, and unflagging attention to the minutest articles of expense and profit, he may attain riches. It is done every day. But let not this person also expect to enjoy 'the pleasures of leisure, of a vacant mind, of a free, unsuspicious temper.' He must learn to do hard things, to have at the utmost a homespun sort of honesty, to be in a great measure a drudge. I cannot submit to all this.' Very good, be above it; only do not repine that you are not rich. How strange to see an illiterate fellow attaining to wealth and social importance, while a profound scholar remains poor and of little account! If, however, you have chosen the riches of know-ledge, be content with them. The other person has paid health, conscience, liberty for his wealth. Will you envy him his bargain? 'You are a modest man-you love quiet and independence, and have a delicacy and reserve in your temper, which renders it impossible for you to elbow your way in the world and be the hero of your own merits. Be content then with a modest retirement, with the esteem of your intimate friends, with the praises of a blameless heart, and a delicate, ingenuous spirit; but resign the splendid distinctions of the world to those who can better scramble for them.' The essayist remarks that men of genius are of all others most inclined to make unreasonable claims. 'As their relish for enjoyment,' says she, 'is strong, their views large and. comprehensive, and they feel themselves lifted above the common bulk of mankind, they are apt to slight that natural reward of praise and admiration which is ever largely paid to distinguished abilities; and to expect to be called forth to public notice and favour: without considering that their talents are commonly unfit for active life; that their eccentricity and turn for speculation disqualifies them for the business of the world, which is best carried on by men of moderate genius; and that society is not obliged to reward any one who is not useful to it. The poets have been a very unreasonable race, and have often complained loudly of the neglect of genius and the ingratitude of the age. The tender and pensive Cowley, and the elegant Shenstone, had their minds tinctured by this discontent; and even the sublime melancholy of Young was too much owing to the stings of disappointed ambition.' MISS LINWOOD'S EXHIBITION OF NEEDLEWORKFor nearly half a century, in old Savile House, on the north side of Leicester-square, was exhibited the gallery of pictures in needlework which Miss Mary Linwood, of Leicester, executed through her long life. She worked her first picture when thirteen years old, and the last piece when seventy-eight; beyond which her life was extended twelve years. Genius, virtue, and unparalleled industry had, for nearly three-quarters of a century, rendered her residence an honour to Leicester. As mistress of a boarding-school, her activity continued to her last year. In 1844, during her annual visit to her Exhibition in London, she was taken ill, and conveyed in an invalid carriage to Leicester, where her health rallied for a time, but a severe attack of influenza terminated her life in her ninetieth year. By her death, many poor families missed the hand of succour, her benevolent disposition and ample means having led her to minister greatly to the necessities of the poor and destitute in her neighbourhood.  No needlework, either of ancient or modern times, (says Mr. Lambert,) has ever surpassed the productions of Miss Linwood. So early as 1785, these pictures had acquired such celebrity as to attract the attention of the Royal Family, to whom they were shewn at Windsor Castle. Thence they were taken to the metropolis, and. shewn privately to the nobility at the Pantheon, Oxford-street; in 1708, they were first exhibited publicly at the Hanover-square Rooms; whence they were removed to Leicester-square. The pictures were executed with fine crewels, dyed under Miss Linwood's own superintendence, and worked on a thick tammy woven expressly for her use: they were entirely drawn and embroidered by herself, no background or other important parts being put in by a less skilful hand-the only assistance she received, if such it may be called, was in the threading of her needles. The pictures appear to have been cleverly set for picturesque effect. The principal room, a fine gallery, was hung with scarlet cloth, trimmed with gold; and at the end was a throne and canopy of satin and silver. A long dark passage led to a prison cell, in which was Northcote's Lady Jane Grey Visited by the Abbot and Keeper of the Tower at Night; the scenic illusion being complete. Next was a cottage, with casement and hatch-door, and within it Gainsborough's cottage children, standing by the fire, with. chimney-piece and furniture complete. Near to this was a den, with lionesses; and further on, through a cavern aperture was a brilliant sea-view and picturesque shore. The large picture by Carlo Dolci had appropriated to it an entire room. The large saloons of Savile House were well adapted for these exhibition purposes, by insuring distance and effect. The collection ultimately consisted of sixty-four pictures, most of them of large or gallery size, and copied from paintings by great masters. The gem of the collection, Salvator Mundi, after Carlo Dolci, for which 3,000 guineas had been refused, was bequeathed by Miss Linwood to her Majesty Queen Victoria. In the year after Miss Linwood's death, the pictures were sold by auction, by Christie and Manson; and the prices they fetched denoted a strange fall in the money-value of these curious works. The Judgment on Cain, which had occupied ten years working, brought but £641s.; Jephtha's Rash Vow, after Opie, sixteen guineas; two pictures from Gainsborough, The Shepherd Bay, £17 6s. 6d., and The Ass and Children, £23 2s. The Farmer's Stable, after Morland, brought £32 11s. and A Woodman in a Storm, by Gainsborough, A portrait of Miss Linwood, after a crayon pia- £33 Is. 6d. Barker's Woodman brought £29 Ss.; The Girl and Kitten, by Sir Joshua Reynolds, £10 15s.; and Lady Jane Grey, by Northcote, £24 13s. In the Scripture-room, The Nativity, by Carlo Maratti, was sold for £21; Dead Christ, L. Caracci, fourteen guineas; but The Madonna Bella Sedia, after Ila$'aelle, was bought in at £3S 17s. A few other pictures were reserved; and those sold did not realize more than £1,000. OLD LONDON SHOPSBusiness in the olden time was conducted in a far more open way than among ourselves. Advertising in print was an art undiscovered. A dealer advertised by word of month from an open shop, proclaiming the qualities of his wares, and inviting passengers to come and buy them. The principal street of a large town thus became a scene of noisy confusion. The little we know of the ancient state of the chief London thorough-fares, shews this to have been their peculiarity. In the south of Europe we may still see something of the aspect which the business streets of old London must have presented in the middle ages; but the eastern towns, such as Constantinople or Cairo, more completely retain these leading characteristics, in ill-paved streets, crowded markets, open shops disconnected with dwelling-houses, and localities sacred to particular trades. The back streets of Naples still possess similar arrangements, which most have existed there unchanged for centuries. The shops are vaulted cells in the lower story of the houses, and are closed at night by heavy doors secured by iron bars and massive padlocks. In the drawings preserved in mediaeval manuscripts we see such shops delineated. Our first cut, copied from one of the best of these pictures, executed about 1190, represents the side of a street apparently devoted to a confraternity of mercers, who exhibit hats, shoes, stockings, scarfs, and other articles in front of their respective places of business; each taking their position at the counter which projects on the pathway, and from whence they addressed wayfarers when they wanted a customer. Lydgate, the monk of Bury, in his curious poem called London Lack penny, has described the London shops as he saw them at the close of the fourteenth century: Where Flemyngs to me began to cry, 'Master, what will you cheapen or buy? Fine felt hats, or spectacles to read; Lay down your silver and here you may speed.'  He afterwards describes the streets crowded with peripatetic traders. 'hot peascods' one began to cry, and others strawberries and cherries, while 'one bade me come near and buy some spice;' but he passes on to Cheapside, then the grand centre of trade, and named from the great market or cheap established there from very early time: Then to the Cheap my steps were drawn, Where much people I there saw stand; One offered me velvet, silk, and lawn, 'Here is Faris thread, the finest in the land!' Tempting as all offers were, his lack of money brought him safely through the throng: Then went I forth by London stone, Throughout all Canwyke-street; Drapers much cloth me offered anon, Then comes me one, cried, 'Hot sheepes feet!' Among the crowd another cried 'Mackerell!' and he was again hailed by a shopkeeper, and invited to buy a hood. The Liber Albus, a century before Lydgate, describes these shops, which consisted of open rooms closed at night by shutters, the tenants being enjoined to keep the space before their shops free of dirt, nor were they to sweep it before those of other people. At that time paving was unknown, open channels drained the streets in the centre, and a few rough stones might be placed in some favoured spots; but mud and mire, or dust and ruts, were the most usual condition of the streets. On state occasions, such as the entry of a sovereign, or the passage to Westminster of a coronation procession from the Tower, the streets were levelled, ruts and gulleys filled in, and the road new gravelled; but these attentions were seldom bestowed, and the streets, of course, soon lapsed into their normal condition of filthy neglect. The old dramatists, whose works often preserve unique and valuable records of ancient usages, incidentally allude to these old shops; thus in Middleton's comedy, The Roaring Girl, 1611, Moll Cutpurse, from whom the play is named, refuses to stay with some jovial companions: I cannot stay now, 'faith: I am going to buy a shag-ruff: the shop will be shut in presently.' One of the scenes of this play occurs before a series of these open shops of city traders, and is thus described: 'The three shops open in a rank [like those in our cut]: the first an apothecary's shop; the next a feather shop; the third a sempster's shop;' from the last the passengers are saluted with 'Gentlemen, what is't you lack? what is't you buy? see fine bands and ruffs, fine lawns, fine cambricks: what is't you lack, gentlemen? what is't you buy? 'This cry for custom is often contemptuously alluded to as a characteristic of a city trader; and in the capital old comedy Eastward Hoe, the rakish apprentice Quick-silver asks his sober fellow-apprentice, 'What! wilt thou cry, what is't ye lack? stand with a bare pate, and a dropping nose, under a wooden penthouse.'  This dialogue takes place in the shop of their master, 'Touchstone, a honest goldsmith in the city;' its uncomfortable character, and the exposure of the shopkeeper to all weathers, is fully confirmed by the glimpses of street scenery we obtain in old topographic prints. Faithorne's view of Fish-street and the Monument represents a goldsmith's open shop with its wooden penthouse; it appears little better than a shed, with a few shelves to hold the stock; and a counter, behind which the master is ensconced. It shews that no change for the better as regarded the comfort of shopkeepers was made by the Groat Fire of London. With the Revolution came a government well-defined in the Bill of Rights, and a consequent additional security to trade and commerce. Traders increased, and London enlarged itself; yet local government continued lax and bad; streets were unpaved, ill-lighted, and dangerous at night. Shops were still rude in construction, open to wind and weather, and most uncomfortable to both salesman and buyer. A candle stuck in a lantern swung in the night breezes, and gave a dim glare over the goods. The wooden penthouse, which imperfectly protected the wares from drifts of rain, was succeeded by a curved projection of lath and plaster. Our third cut, from a print dated 1736, will clearly exhibit this, as well as the painted sign (a greyhound) over the door; the shop front is furnished with an open railing, which encloses the articles exposed for sale; in this instance, fruit is the vendible commodity, and oranges in baskets appear piled under the window. The lantern ready for lighting hangs on one side.  The custom of noting inns by signs, was succeeded by similarly distinguishing the houses of traders; consequently in the seventeenth century sign-painting flourished, and the practice of the 'art' of a sign-painter was the most profitable branch of the fine arts left open to Englishmen. The houses in London not being numbered, a tradesman could only be known by such means; hence every house in great leading thorough-fares displayed its sign; and the ingenuity of traders was taxed for new and characteristic devices by which their shops might be distinguished. The sign was often engraved as a 'heading' to the shop-bill; and many whimsical and curious combinations occurred from the custom of an apprentice or partner in a well-known house adopting its sign in addition to a new device of his own. These signs were sometimes stuck on posts, as we see them in country inns, between the foot and carriage way. In narrow streets they were slung across the road. More generally they projected over the footpath, supported by ironwork which was wrought in an elaborate, ornamental style. A young tradesman made his first and chiefest outlay in a new sign, which was conspicuously painted and gilt, surrounded by a heavy, richly carved, and painted frame, and then suspended from massive decorative ironwork. Cheapside was still the coveted locality for business, and the old views of that favoured locality are generally curious from the delineation of the line of shops, and crowd of signs, that are presented on both sides the way. From a view of Bow Church and neighbourhood published by Bowles in 1751, we select the two examples of shops engraved below. The two modes of suspending the signs are those generally in vogue. In one instance the shop is enclosed by glazed windows; in the other it is open. The latter is a pastrycook's; a cake on a stand occupies the centre of the bracketed counter, which is protected by a double row of glazing above.  Still the whole is far from weatherproof, and a heavy drifting rain must have been a serious inconvenience when it happened, not to speak of the absolute damage it must have done. The mercers, hatters, and shoemakers made their places of business distinguished by throwing out poles, such as we see at the shops of country barbers, at an angle from the shop-front over the foot-path, hanging rows of stockings, or lines of hats, &c., upon them. When a shower came, these could at once be hauled in, and saved from damage; but the signs swung and grated in the breeze, or collected water in the storm, which descended on the unlucky pedestrian, for whom no umbrella had, as yet, been invented. The spouts from the houses, too, were ingeniously contrived to condense and pour forth a volume of water which wavered in the wind, and made the place of its fall totally uncertain; a few rough semi-globular stones formed a rude pavement in places; but it was often in bad condition, for each householder was allowed to do what he pleased in this way, and sometimes he solved the difficulty of doubting what was best by doing nothing at all. The pedestrian was protected from carriages by a line of posts, as seen in our cut; but he was constantly liable to be thrust in the gutter, or driven into a door-way or shop, by the sedan-chairs that crowded the streets, and which were thoroughly hated by all but the wealthy who used them, and those who profited by their use. 'The art of walking the streets of London' was therefore an art, necessary of acquirement by study, and Gay's poem, which bears the title, is an amusing picture of all the difficulties which beset pedestrianism when the wits of Queen Anne's reign rambled from tavern to tavern, to gather news or enjoy social converse.' These ponderous signs, with their massive iron frameworks, as they grew old, grew dangerous; they would rot and fall, and when this did not occur, they 'made night hideous' by the shrieks and groans of the rusty hinges on which they swung. They impeded sight and ventilation in narrow streets, and sometimes hung inconveniently low for vehicles. At last they were doomed by Act of Parliament, and in 1762 ordered to be removed, or, if used, to be placed flat against the fronts of the houses. They had increased so enormously that every tradesman had one, each trying to hide and outvie his neighbour by the size or colour of his own, until it became a tedious task to discover the shop wanted. Gay, in his 'Trivia,' notes how Oft the peasant, with inquiring face, Bewildered, trudges on from place to place; He dwells on every sign with stupid gaze, Enters the narrow alley's doubtful maze, Tries every winding court and street in vain, And doubles o'er his weary steps again. In addition to swinging painted sign-boards, it was sometimes the habit with the rich and ambitious trader to engage the services of the wood-carver to decorate his house with figures or emblems, the figures being those of some animal or thing adopted for his sign, as the stag seen over one of the doors in the cut of the Cheapside shops; or else representations, modelled and coloured 'after life,' of pounds of candles, rolls of tobacco, cheeses, &c. &c.  There existed in St. Martin's-lane, twenty years ago, a fine example of a better-class London shop, of which we here give a wood-cut. It had survived through many changes in all its essential features. The richly carved private door-case told of the well-to-do trader who had erected it. The shop was an Italian warehouse; and the window was curiously constructed, carrying out the traditional form of the old open shop with its projecting stall on brackets, and its slight window above, but effecting a compromise for security and comfort by enclosing the whole in a sort of glass box; above which the trade of the occupant was shewn more distinctly in the small oil-barrels placed upon it, as well as by the models of candles which hung in bunches from the canopy above. The whole of this framework was of timber richly carved throughout with foliated ornament, and was unique as a surviving example of the better class shops of the last century. It was in the early part of the reign of George I that shops began to be closed in with sash-windows, allowing them to be open in fine weather, but giving the chance of closing them in winter and during rain. Addison alludes to it in the Tatler, as if it was a somewhat absurd luxury. 'Private shops,' says he, 'stand upon Corinthian pillars, and whole rows of tin pots show themselves, in order to their sale, through a sash window.' A great improvement of the most economic and simple kind succeeded the old and expensive signs. This was numbering houses in a street. The first street so numbered was New Burlington-street, in June 1764. The fashion spread eastward, and the houses in Lincoln's-inn-fields were the next series thus distinguished. The old traders who stuck pertinaciously to their signs, affixed them flat to their walls, and a few thus preserved rot in obscurity in some of our lonely old streets; one of the earliest and most curious is 'The Doublet,' in Thames-street, which seems to have originated in the days of Elizabeth, and to have been painted and repainted from time to time, till it is now scarcely distinguishable. The once-famed inn, used by Shakspeare, 'The Bell,' in Great Carter-lane, is no longer an inn; but its sign, a bell, boldly sculptured in high relief, and rich in decoration, is still on its front. Other sculptured signs remain on city houses, but units now represent the hundreds that once existed. At the corner of Union-street, Southwark, where it opens on the Blackfriars-road, is a well-executed old sign; a gilt model, life-size, representing a dog licking an overturned cooking-pot. It is curious that this very sign is mentioned in that strange old poem, 'Cock Lorell's Boat' (published by Wynkyn de Worde, in the early part of the reign of Henry VIII): one of the passengers is described as dwellingat the Sygne of the dogges lied in the pot.'  In Holywell-street, Strand, is the last remaining shop sign in situ, being a boldly-sculptured half-moon, gilt, and exhibiting the old conventional face in the centre. Some twenty years ago it was a mercer's shop, and the bills made out for customers were 'adorned with a picture' of this sign. It is now a bookseller's, and the lower part of the windows have been altered into the older form of open shop. A court beside it leads into the great thoroughfare; and the corner-post is decorated with a boldly-carved lion's head and paws, acting as a corbel to support a still older house beside it. This street altogether is a good, and now an almost unique specimen of those which once were the usual style of London business localities, crowded, tortuous, and ill-ventilated, having shops closely and inconveniently packed, but which custom had made familiar and inoffensive to all; while the old traders, who delighted in 'old styles,' looked on improvements with absolute horror, as 'a new-fashioned way' to bankruptcy. A FORTUNE-TELLER OF THE LAST CENTURYEarly in the year 1789, died in the Charter-house, Isaac Tarrat, a man of some literary merit, who had actually practised the arts of a fortune-teller. Originally a linendraper in the city, and a thriving one, he had from various causes proved ultimately unsuccessful, and at seventy knew not how to obtain his bread. One who had contributed, as he had done, to the Ladies' Diary and the Gentleman's Magazine, would have now been at no loss to live by the press; it was different in those days, and Tarrat was reduced to become a fortune-teller. In a mean street near the Middlesex Hospital, there was an obscure shop kept by an elderly woman, who had long made a livelihood by means of an oracle maintained on the premises. It became the office of Mr. Tarrat to sit in an upper room, in a fur cap, a white beard, and a flowing worsted damask night-gown, and tell the fortunes of all who might apply. The woman sat in the front shop, receiving the company, and taking their money. 'The Doctor' was engaged in this duty at a shilling a day and his food. He admitted that his mistress treated him kindly, always giving him a small howl of punch after supper; there was no great discomfort in his situation, beyond the constant distress of mind he suffered from reflecting on the infamous character of his occupation. He had occasion to remark with surprise that many of his customers were of less mean and illiterate appearance than might be expected. At length, having scraped together a small amount of cash, Tarrat gave up his place-and he did so just in time, as his successor had not been a month in office when he was taken up as an impostor. Poor Tarrat afterwards found a retreat in the Charter-house, and there contrived to make the thread of life spin out to eighty-eight. The Profession of a Conjurer, a hundred years ago, was by no means uncommon, nor does it seem to have been thought a discreditable one. A person named Hassell was in full practice as a cunning man in the neighbourhood of Tunbridge Wells, very recently. One of the best known of his craft (in Sussex), was a man of the name of Sanders, of Heathfield, who died about 1807. He was a respectable man, and at one time in easy circumstances, but he neglected all earthly concerns for astrological pursuits, and, it is said, died in a workhouse. |