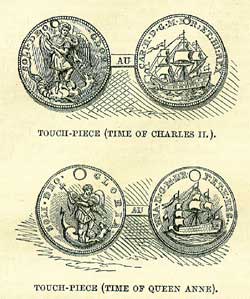

9th JanuaryBorn: John Earl St. Vincent (Admiral Jervis), 1734. Died: Bernard de Fontenelle, philosopher, 1757; Thomas Birch, biographical and historical writer, 1766; Elizabeth O. Benger, historian, 1822; Caroline Lucretia Herschel, astronomer, 1848. Feast Day: Saints. Julian and Basilissa, martyrs, 313. St. Peter of Sebaste, bishop and confessor, about 387. St. Marchiana, virgin and martyr, about 305. St. Vaneng, confessor, about 688. St. Fillan, abbot, 7th century. St. Adrian, abbot at Canterbury, 710. St. Brithwald, archbishop of Canterbury, 731. ST. FILLANSt. Fillan is famous among the Scottish saints, from his piety and good works. He spent a considerable part of his holy life at a monastery which he built in Pittenweem, of which some remains of the later buildings yet exist in a habitable condition. It is stated that, while engaged here in transcribing the Scriptures, his left hand sent forth. sufficient light to enable him, at night, to continue his work without a lamp. For the sake of seclusion, he finally retired to a wild and lonely vale, called from him Strathfillan, in Perthshire, where he died, and where his name is still attached to the ruins of a chapel, to a pool, and a bed of rock. 'At Strathfillan, there is a deep pool, called the Holy Pool, where, in olden times, they were wont to dip insane people. The ceremony was performed after sunset on the first day of the quarter, O.S., and before sunrise next morning. The dipped persons were instructed to take three stones from the bottom of the pool, and, walking three times round each of three cairns on the bank, throw a stone into each. They were next conveyed to the ruins of St. Fillan's chapel; and in a corner called St. Fillan's bed, they were laid on their back, and left tied all night. If next morning they were found loose, the cure was deemed perfect, and thanks returned to the saint. The pool is still (1843) visited, not by parishioners, for they have no faith in its virtue, but by people from other and distant places.' Strange as it may appear, the ancient bell of the chapel, believed to have been St. Fillan's bell, of a very antique form, continued till the beginning of the nineteenth century to lie loose on a grave-stone in the churchyard, ready to be used, as it occasionally was, in the ceremonial for the cure of lunatics. The popular belief was, that it was needless to attempt to appropriate and carry it away, as it was sure, by some mysterious means, to return. A curious and covetous English traveller at length put the belief to the test, and the bell has been no more heard of. The head of St. Fillan's crosier, called the Quigrich, of silver gilt, elegantly carved, and with a jewel in front, remained at Killin, in the possession of a peasant's family, by the representative of which it was conveyed some years ago to Canada, where it still exists. The story is that this family obtained possession of the Quigrich from King Robert Bruce, after the battle of Bannockburn, on his becoming offended with the abbot of Inchaffray, its previous keeper; and there is certainly a document proving its having been in their possession in the year 1487. A relic of St. Hector figures in Hector Bocce's account of the battle just alluded to. 'King Robert,' says he, 'took little rest the night before the battle, having great care in his mind for the surety of his army, one while revolving in his consideration this chance, and another while that: yea, and sometimes he fell to devout contemplation, making his prayer to God and St. Fillan, whose arm, as it was set and enclosed in a silver case, he supposed had been the same time within his tent, trusting the better fortune to follow by the presence thereof. As he was thus making his prayers, the case suddenly opened and clapped to again. The king's chaplain being present, astonished therewith, went to the altar where the case stood, and finding the arm within it, he cried to the king and others that were present, how there was a great miracle wrought, confessing that he brought the empty case to the field, and left the arm at home, lest that relic should have been lost in the field, if anything chanced to the army otherwise than well. The king, very joyful of this miracle, passed the remnant of the night in prayer and thanksgiving.' LORD ST. VINCENTIn the history of this great naval commander, we have a remarkable instance of early difficulties overcome by native hardihood and determination. The son of a solicitor who was treasurer to Greenwich Hospital, he received a good education, and was designed for the law; but this was not to be his course. To pursue an interesting recital given by himself: 'My father's favourite plan was frustrated by his own coachman, whose confidence I gained, always sitting by his side on the coach-box when we drove out. He often asked what profession I intended to choose. I told him I was to be a lawyer. 'Oh, don't be a lawyer, Master Jackey,' said the old man; 'all lawyers are rogues.' About this time young Strachan (father of the late Admiral Sir Richard Strachan, and a son of Dr. Strachan, who lived at Greenwich) came to the same school, and we became great friends. He told me such stories of the happiness of a sea life, into which he had lately been initiated, that he easily persuaded me to quit the school and go with him. We set out accordingly, and concealed ourselves on board of a ship at Woolwich. 'After three days' absence, young Jervis returned home, and persisted in not returning to school. 'This threw my mother into much perplexity, and, in the absence of her husband, she made known her grief, in a flood of tears, to Lady Archibald Hamilton, mother of the late Sir William Hamilton, and wife of the Governor of Greenwich Hospital. Her ladyship said she did not see the matter in the same light as my mother did, that she thought the sea a very honourable and a very good profession, and said she would undertake to procure me a situation in some ship-of-war. In the meantime my mother sent for her brother, Mr. John Parker, who, on being made acquainted with my determination, expostulated with me, but to no purpose. I was resolved I would not be a lawyer, and that I would be a sailor. Shortly afterwards Lady Archibald Hamilton introduced me to Lady Burlington, and she to Commodore Townshend, who was at that time going out in the Gloucester, as Commander-in-Chief, to Jamaica. She requested that he would take me on his quarter-deck, to which the commodore readily consented; and I was forthwith to be prepared for a sea life. My equipment was what would now be called rather grotesque. My coat was made for me to grow up to; it reached down to my heels, and was full large in the sleeves; I had a dirk, and a gold-laced hat; and in this costume my uncle caused me to be introduced to my patroness, Lady Burlington. Here I acquitted myself but badly. I lagged behind my uncle, and held by the skirt of his coat. Her ladyship, however, insisted on my coming forward, shook hands with me, and told me I had chosen a very honourable profession. She then gave Mr. Parker a note to Commodore George Townshend, who lived in one of the small houses in Charles Street, Berkeley Square, desiring that we should call there early the next morning. This we did; and after waiting some time, the commodore made his appearance in his night-cap and slippers, and in a very rough and uncouth voice asked me how soon I would be ready to join my ship? I replied, 'Directly.' 'Then you may go tomorrow morning,' said he, ' and I will give you a letter to the first lien-tenant.' My uncle, Mr. Parker, however, replied that I could not be ready quite so soon, and we quitted the commodore. In a few days after this we set off, and my uncle took me to Mr. Blanchard, the master-attendant or the boatswain of the dockyard-I forget which-and by him I was taken on board the hulk or receiving-ship the next morning, the Gloucester being in dock at the time. This was in the year 1748. As soon as the ship was ready for sea we proceeded to Jamaica, and as I was always fond of an active life, I voluntered to go into small vessels, and saw a good deal of what was going on. My father had a very large family, with limited means. He gave me twenty pounds at starting, and that was all he ever gave me. After I had been a consider-able time at the station, I drew for twenty more, but the bill came back protested. I was mortified at this rebuke, and made a promise, which I have ever kept, that I would never draw another bill, without a certainty of its being paid. I immediately changed my mode of living, quitted my mess, lived alone, and took up the ship's allowance, which I found to be quite sufficient; washed and mended my own clothes, made a pair of trousers out of the ticking of my bed, and, having by these means saved as much money as would redeem my honour, I took up my bill; and from that time to this ' (he said this with great energy) ' I have taken care to keep within any means.' FONTENELLEFontenelle stands out amongst writers for having reached the extraordinary age of a hundred years. He was probably to a great extent indebted for that length of days to a calmness of nature which forbade the machine to be subjected to any rough handling. It was believed of him that he had never either truly laughed or truly cried in the whole course of his existence. His leading characteristic is conveyed in somebody's excellent mot on hearing him say that he flattered himself he had a good heart: 'Yes, my dear Fontenelle, as good a heart as can be made out of brains.' Better still in an anecdote which has got into currency: 'One day, a certain bon-vivant abbé came unexpectedly to dine with him. The abbé was fond of asparagus dressed with butter; for which Fontenelle also had a great goût, but preferred it dressed with oil. Fontenelle said for such a friend there was no sacrifice he would not make: the abbé should have half the dish of asparagus he had ordered for himself, and, more-over, it should be dressed 'with butter. While they were conversing thus together, the poor abbé fell down in a fit of apoplexy; upon which his friend Fontenelle instantly scampered down stairs, and eagerly called out to his cook: 'The whole with oil! the whole with oil, as at first!' Fontenelle was born at Rouen, 11th February, 1657, and was, by his mother's side, nephew of the great Corneille. He was bred to the law, which he gave up for poetry, history, and philosophy. His poetical pieces have, however, fallen into neglect and oblivion. The Dialogues des Morts, published in 1683, first laid the foundation of his literary fame. He was the first individual who wrote a treatise expressly on the Plurality of Worlds. It was published in 1686, the year before the publication of Newton's Principia. and is entitled Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds. It consists of five chapters, with the following titles:

In another edition of the work published in 1719, Fontenelle added a sixth chapter, entitled, 6. New thoughts which confirm those in the preceding conversations-the latest discoveries which have been made in the heavens. This singular work, written by a man of great genius, and with a sufficient knowledge of astronomy, excited a high degree of interest, both from the nature of the subject, and the vivacity and humour with which it is treated. The conversations are carried on with the Marchioness of G---- with whom the author is supposed to be residing. The lady is distinguished by youth, beauty, and talent, and the share which she takes in the dialogue is not less interesting than the more scientific part assumed by the philosopher. The Plurality of Worlds (says Sir David Brewster) was read with unexampled avidity through every part of Europe. It was translated into all the languages of the Continent, and was honoured by annotations from the pen of the celebrated astronomer Lalande; and of M. Gottsched, one of its German editors. No fewer than three English translations of it were published; and one of these, we believe the first, had run through six editions so early as the year 1737. We have given this outline of Foutenelle's celebrated work in consequence of the great attention which its subject, the Plurality of Worlds, has of late excited in scientific circles. One of the leading controversialists has been the author of an Essay on the Plurality of Worlds, who urges the theological, not less than the scientific, reasons for believing in the old tradition of a single world: 'I do not pretend,' says this writer, 'to disprove the plurality of worlds; but I ask in vain for any argument which makes the doctrine probable.' ... 'It is too remote from knowledge to be either proved or disproved.' Sir David Brewster has replied in More Worlds than One, emphatically maintaining that analogy strongly countenances the idea of all the solar planets, if not all worlds in the universe, being peopled with creatures, not dissimilar in being and nature to that of the inhabitants of the earth. CAROLINE LUCRETIA HERSCHEL [Caroline] was one of those women who occasionally come forth before the world, as in protest against the commonly accepted ideas of men regarding the mental capacity of the gentler sex. Of all scientific studies one would suppose that of mathematics to be the most repulsive to the female mind; yet what instances there are of the contrary! Jeanne Dumée, the widow who sought solace for her desolate state in the study of the Copernican theory; Marie Caunitz, who assisted her husband in making up his Mathematical Tables; the Marquise de Chatelet, the friend of Voltaire, Maupertuis, and Bernouilli, who published in 1740 her Institution de Physique, an exposition of the philosophy of Leibnitz, and who likewise translated the Principia of Newton; Nicole de Lahière, who helped her husband Lefante with a Treatise on the Lengths of Pendulums; the Italian Agnosi, who wrote and debated on all learned subjects, a perfect Admirable Crichton in petticoats, and whose mathematical treatises yet command admiration: finally, another fair Italian, Maria Catarina Bassi, who was equally conversant with classical and mathematical studies, and actually attained the honours of a professor's chair in the university of Bologna. Such examples are certainly enough to prove that, whatever may be the ordinary or average powers and tendencies of the female mind, there is nothing in its organization absolutely to forbid an occasional competency for the highest subjects of thought. Isaac Herschel and his wife use little thought, when he was plying his vocation as a musician at Hanover, what a world-wide reputation was in store for their family. He taught them all music-four sons and a daughter. The second son, William, came to England to seek his fortune in 158; and when, after many difficulties, he became organist at Bath, his sister Caroline came over to live with him. In time, turning his attention to telescopes and astronomy, and gaining the favour of George III, he became the greatest practical astronomer of his age. For more than forty years did the brother pursue his investigations at Slough, near Windsor, Caroline assisting him. It is stated that when he became for ten or twelve hours at a time absorbed in study, Miss Herschel sometimes found it necessary to put food into his mouth, as otherwise he would have neglected even that simplest of nature's needs. The support of the pair was assured by a pension from the king, who did himself honour by conferring on William Herschel the honour of knighthood. In 1798 Caroline Herschel published a Catalogue of Stars, at the expense of the Royal Society, which has ever since been highly valued by practical astronomers. After a noble career, Sir William died in 1822; and his sister then went to spend the rest of her days at Hanover. She afterwards prepared a Catalogue of Nebulae and Star-Clusters, observed by her brother. It was an event worth remembering, when, on the 8th of February 1828, the Astronomical Society's gold medal was awarded to Caroline Herschel. Her nephew John, now the eminent Sir J. F. W. Herschel, was President of the Society, and shrank from seeming to bestow honour on his own family; but the Council worthily took the matter in hand. Sir James South, in an address on the occasion, after adverting to the labours of Sir William Herschel, said: 'Who participated in his toils? Who braved with him the inclemency of the weather? Who shared his privations? A female! Who was she? His sister. Miss Herschel it was who, by night, acted as his amanuensis. She it was whose pen conveyed to paper his observations as they issued from his lips; she it was who noted the right ascensions and polar distances of the objects observed; she it was who, having passed the night near the instruments, took the rough manuscripts to her cottage at the dawn of day, and produced a fine copy of the night's work on the subsequent morning; she it was who planned the labour of each succeeding night; she it was who reduced every observation and made every calculation; she it was who arranged everything in systematic order; and she it was who helped him to obtain an imperishable name. But her claims to our gratitude end not here. As an original observer, she demands, and I am sure has, our most unfeigned thanks. Occasionally, her immediate attention during the observations could be dispensed with. Did she pass the night in repose ? No such thing. Wherever her illustrious brother was, there you were sure to find her also.' As one remarkable fact in her career, she discovered seven comets, by means of' a telescope which her brother made expressly for her use. It was not until the extraordinary age of ninety-seven that this admirable woman closed her career, Her intellect was clear to the last; and princes and philosophers alike strove to do her honour. The foregoing portrait-in which, notwithstanding age and decay, we see the lineaments of intellect and force of character,-is from a sketch in the possession of Sir John Herschel. TOUCHING OF THE EVILOn this day in the year 1683, King Charles II in council at Whitehall, issued orders for the future regulation of the ceremony of Touching for the King's Evil. It was stated that 'his Majesty, in no less measure than his royal predecessors, having had good success therein, and in his most gracious and pious disposition being as ready as any king or queen of this realm ever was, in any thing to relieve the necessities and distresses of his good subjects,' it had become necessary to appoint fit times for the 'Publick Healings;' which therefore were fixed to be from All-Hallow-tide till a week before Christmas, and after Christmas until the first week of March, and then cease till Passion week; the winter being to be preferred for the avoidance of contagion. Each person was to come with a recommendation from the minister or churchwardens of his parish, and these individuals were enjoined to examine carefully into the cases before granting such certificates, and in particular to make sure that the applicant had not been touched for the evil before. Scrofula, which is the scientific name of the disease popularly called the King's evil, has been described as 'indolent glandular tumours, frequently in the neck, suppurating slowly and imperfectly, and healing with difficulty.' (Good's Study of Medicine.) This is the kind of disease most likely to be acted upon by the mind in a state of excitement. The tumours maybe stimulated, and the suppuration quickened and increased, which is the ordinary process of cure. Whether the result be produced through the agency of the nerves, or by an additional flow of blood to the part affected, or by both, has not perhaps been clearly ascertained: but that cures in such cases are effected by some such natural means, is generally admitted by medical practitioners; and it is quite credible that, out of the hundreds of persons said to have been cured of king's evil by the royal touch, many have been restored to health by the mind under excitement operating on the body. In all such cases, however, the probability of cure may be considered as in proportion to the degree of credulity in the person operated upon, and as likely to be greatest where the feeling of reverence or veneration for the operator is strongest. As society becomes instructed in the causes and nature of diseases, and the methods of cure established by medical experience, the belief in amulets, charms, and the royal touch passes away from the human mind, together with all the other superstitions which were so abundant in ages of ignorance, and of which only a few remains still linger among the most uninstructed classes of society. The practice of touching for the king's evil had its origin in England from Edward the Confessor, according to the testimony of William of Malmesbury, who lived about one hundred years after that monarch. Mr. Giles's translation of this portion of the Chronicle of the Kings of England is as follows: 'But now to speak of his miracles. A young woman had married a husband of her own age, but having no issue by the union, the humours collecting abundantly about her neck, she had contracted a sore disorder, the glands swelling in a dreadful manner. Admonished in a dream to have the part affected washed by the king, she entered the palace, and the king himself fulfilled this labour of love by rubbing the woman's neck with his hands dipped in water. Joyous health followed his healing hand; the lurid skin opened, so that worms flowed out with the purulent matter, and the tumour subsided; but as the orifice of the ulcer was large and unsightly, he commanded her to be supported at the royal expense till she should be perfectly cured. However, before a week was expired, a fair new skin returned, and hid the ulcers so completely that nothing of the original wound could be discovered. Those who knew him more intimately affirm that he often cured this complaint in Normandy; whence appears how false is their notion who in our times assert that the cure of this disease does not proceed from personal sanctity, but from hereditary virtue in the royal line.' Shakespeare describes the practice of the holy king in his tragedy of Macbeth, 'the gracious Duncan' having been contemporary with Edward the Confessor: Macduff.-What's the disease he means? Malcolm.- 'Tis called the evil; A most miraculous work in this good king; Which often, since my here-remain in England, I've seen him do. How he solicits heaven Himself best knows; but strangely-visited people, All swoln and ulcerous, pitiful to the eye, The mere despair of surgery, he cures; Hanging a golden stamp about their necks, Put on with holy prayers: and 'tis spoken, To the succeeding royalty he leaves The healing benediction. With this strange virtue He hath a heavenly gift of prophecy; And sundry blessings hang about his throne, That speak him full of grace. Holinshed's Chronicle is Shakespeare's authority, but by referring to the passage it will be seen that the poet has mixed up in his description the practice of his own times. Referring to Edward the Confessor, Holinshed writes as follows: As it has been thought, he was inspired with the gift of prophecy, and also to have the gift of healing infirmities and diseases. He used to help those that were vexed with the disease commonly called the king's evil, and left that virtue, as it were, a portion of inheritance to his successors, the kings of this realm.' Laurentius, first physician to Henry IV of France, in his work DeMirabili Strumas Samando, Paris, 1609, derives the practice of touching for the king's evil from Clovis, A.D. 481, and says that Louis I, A.D. 814, also performed the ceremony with success. Philip de Commines says (Danett's transl., ed. 1614, p. 203), speaking of Louis XI when he was ill at Forges, near Chinon, in 1480: 'He had not much to say, for he was shriven not long before, because the kings of Fraunce use alwaies to confesse themselves when they touch those that be sick of the king's evill, which he never failed to do once a weeke.' There is no mention of the first four English kings of the Norman race having ever attempted to cure the king's evil by touching; but that Henry II performed cures is attested by Peter of Blois, who was his chaplain. John of Gaddesden, who was physician to Edward II and flourished about 1320 as a distinguished writer on medicine, treats of scrofula, and, after describing the methods of treatment, recommends, in the event of failure, that the patient should repair to the court in order to be touched by the king. Bradwardine, Archbishop of Canterbury, who lived in the reigns of Edward III and Richard II, testifies as to the antiquity of the practice, and its continuance in the time when he lived. Sir John Fortes cue, Lord Chief Justice of the Court of King's Bench in the time of Henry IV, and afterwards Chancellor to Henry VI, in his Defence of the Title of the House of Lancaster, written just after Henry IV's accession to the crown, and now among the Cotton manuscripts in the British Museum, represents the practice as having belonged to the kings of England from time immemorial. Henry VII was the first English sovereign who established a particular ceremony to be used on the occasion of touching, and introduced the practice of presenting a small piece of gold. We have little trace of the custom under the eighth Harry; but Cavendish, relating what took place at the court of Francis I of France, when Cardinal Wolsey was there on an embassy in 1527, has the following passage: 'And at his [the king's] coming into the bishop's palace [at Amiens], where he intended to dine with the Lord Cardinal, there sat within a cloister about 200 persons diseased with the king's evil, upon their knees. And the king, or ever he went to dinner, provised every of them with rubbing and blessing them with his bare hands, being bareheaded all the while; after whom followed his almoner, distributing of money unto the diseased. And that done, he said certain prayers over them, and then washed his hands, and came up into his chamber to dinner, where my lord dined with him.' In the reign of Queen Elizabeth, William Tookes published a book on the subject of the cures effected by the royal torch-Charisma; sive Donwm Sanationis. He is a witness as to facts which occurred in his own time. He states that many persons from all parts of England, of all ranks and degrees, were, to his own knowledge, cured by the touch of the Queen; that he conversed with many of them both before and after their departure from the court; observed an incredible ardour and confidence in them that the touch would cure them, and understood that they actually were cured. Some of them he met a considerable time afterwards, and upon inquiry found that they had been perfectly free from the disease from the time of their being touched, mentioning the names and places of abode of several of the persons cured. William Clowes, surgeon to Queen Elizabeth, denominates scrofula 'the King's or the Queen's Evil, a disease repugnant to nature; which grievous malady is known to be miraculously cured and healed by the sacred hands of the Queen's most royal majesty, even by Divine inspiration and wonderful work and power of God, above man's will, art, and expectation.' In the State Paper Office there are preserved no less than eleven proclamations issued in the reign of Charles I respecting the touching for the king's evil. They relate mostly to the periods when the people might repair to the court to have the ceremony performed. In the troubled times of Charles's reign he had not always gold to bestow; for which reason, observes Mr. Wiseman, he substituted silver, and often touched without giving anything. Mr. Wiseman, who was principal surgeon to Charles II after the Restoration, says: 'I myself have been a frequent eye-witness of many hundreds of cures performed by his Majesty's touch alone, without any assistance from chirurgery: The number of cases seems to have increased greatly after the Restoration, as many as 600 at a time having been touched, the days appointed for it being sometimes thrice a week. The operation was often performed at Whitehall on Sundays. Indeed, the practice was at its height in the reign of Charles II. In the first four years after his restoration he touched nearly 24,000 persons.' Pepys, in his Diary, under the date June 23, 1660, says: 'To my lord's lodgings, where Tom Guy came to me, and then staid to see the king touch for the king's evil. But he did not come at all, it rained so; and the poor people were forced to stand all the morning in the rain in the garden. Afterwards he touched them in the Banquetting House.' And again, under the date of April 10, 1661, Pepys says: 'Met my lord the duke, and, after a little talk with him, I went to the Banquet House, and there saw the king heal,-the first time that ever I saw him do it,-which he did with great gravity; and it seemed to me to be an ugly office and a simple one.' One of Charles II's proclamations, dated January 9, 1683, has been given above. Evelyn, in his Diary, March 28, 1684, says: 'There was so great a concourse of people with their children to be touched for the evil, that six or seven were crushed to death by pressing at the chirurgeon's door for tickets.' The London Gazette, October 7, 1686, contains an advertisement stating that his Majesty would heal weekly on Fridays, and commanding the attendance of the king's physicians and surgeons at the Mews, on Thursdays in the afternoon, to examine cases and deliver tickets. Gemelli, the traveller, states that Louis XIV touched 1600 persons on Easter Sunday, 1686. The words he used were: 'Le Roy te touche, Dieu te guérisse' ('The King touches thee; may God cure thee '). Every Frenchman received fifteen sous, and every foreigner thirty. - Barrington's Observations on the Statutes, p. 107. But Charles II and Louis XIV had for a few years a rival in the gift of curing the king's evil by touching. Mr. Greatrakes, an Irish gentleman of the county of Waterford, began, about 1662, to have a strange persuasion in his mind that the faculty of curing the king's evil was bestowed upon him, and upon trial found his touching succeed. He next ventured upon agues, and in time attempted other diseases. In January 1666, the Earl of Orrery invited him to England to attempt the cure of Lady Conway of a headache; he did not succeed; but during his residence of three or four weeks at Ragley, Lord Conway's seat in Warwickshire, cured, as he states, many persons, while others received benefit. From Bagley he removed to Worcester, where his success was so great that he was invited to London, where he resided many months in Lincoln's Inn Fields, and performed many cures.-A brief Account of Mr. Valentine Greatrakes, and divers of the strange cures by him performed; written by himself in a letter addressed to the Hon. Robert Boyle, Esq., whereunto are annexed the testimonials of several eminent and worthy persons of the chief matters of fact there related. London, 1666. The ceremony of touching was continued by James II. In the Diary of Bishop Cartwright, published by the Camden Society, at the date of August 27, 1687, we read: 'I was at his Majesty's levee; from whence, at nine o'clock, I attended him into the closet, where he healed 350 persons.' James touched for the evil while at the French court. Voltaire alludes to it in his Siecle de Louis XIV. William III. never performed the ceremony. Queen Anne seems to have been the last of the English sovereigns who actually performed the ceremony of touching. Dr. Dicken, her Majesty's sergeant surgeon, examined all the persons who were brought to her, and bore witness to the certainty of some of the cures. Dr. Johnson, in Lent, 1712, was amongst the persons touched by the Queen. For this purpose he was taken to London, by the advice of the celebrated Sir John Floyer, then a physician in Lichfield. Being asked if he remembered Queen Anne, Johnson said he had ' a confused, but somehow a sort of solemn recollection of a lady in diamonds, and a long black hood.' Johnson was but thirty months old when he was touched. Carte, the historian, appears to have been not only a believer in the efficacy of the royal touch, but in its transmission in the hereditary royal line; and to prove that the virtue of the touch was not owing to the consecrated oil used at the coronation, as some thought, he relates an instance within his own knowledge of a person who had been cured by the Pretender. (History of England, vol. i. p. 357, note.) 'A young man named Lovel, who resided at Bristol, was afflicted with scrofulous tumours on his neck and breast, and having received no benefit from the remedies applied, resolved to go to the Continent and be touched. He reached Paris at the end of August 1716, and went thence to the place where he was touched by the lineal descendant of a race of kings who had not at that time been anointed. He touched the man, and invested him with a narrow riband, to which a small piece of silver was pendant, according to the office appointed by the Church for that solemnity. The humours dispersed insensibly, the sores healed up, and he recovered strength daily till he arrived in perfect health at Bristol at the beginning of January following. There I saw him without any remains of his complaint.' It did not occur to the learned historian that these facts might all be true, as probably they were, and yet might form no proof that an unanointed but hereditarily rightful king had cured the evil. The note had a sad effect for him, in causing much patron-age to be withdrawn from his book. A form of prayer to be used at the ceremony of touching for the king's evil was originally printed on a separate sheet, but was introduced into the Book of Common Prayer as early as 1684. It appears in the editions of 1707 and 1709. It was altered in the folio edition printed at Oxford in 1715 by Baskett.  Previous to the time of Charles II, no particular coin appears to have been executed for the purpose of being given at the touching. In the reign of Queen Elizabeth, the small gold coin called an angel seems to have been used. The touch-pieces of Charles II are not uncommon, and specimens belonging to his reign and of the reigns of James II and of Queen Anne may be seen in the British Museum. They have figures of St. Michael and the dragon on one side, and a ship on the other. A piece in the British Museum has on one side a hand descending from a cloud towards four heads, with ' He touched them ' round the margin, and on the other side a rose and thistle, with. ' And they were healed.' We have engraved a gold touch-piece of Charles II, obverse and reverse; and the identical touch-piece, obverse and reverse, given by Queen Anne to Dr. Johnson, preserved in the British Museum. THE 'DAVY' AND THE 'GEORDY'On this day, in the year 1816, Davy's safety lamp, for the first time, shed its beams in the dark recesses of a coal-pit. The Rev. John Hodgson, rector of Jarrow, near Newcastle,-a man of high accomplishment, subsequently known for his laborious History of Northumberland,-had on the previous day received from Sir Humphry Davy, two of the lamps which have ever since been known by the name of the great philosopher. Davy, although he felt well-grounded reliance in the scientific correctness of his new lamp, had never descended a coal-pit to make the trial: and Hodgson now determined to do this for him. Coal mines are wont to give forth streams of gas, which, when mixed in certain proportions with atmospheric air, ignite by con-tact with an open flame, producing explosion, and scattering death and destruction around. Till this time, miners were in the habit, when working in foul air, of lighting themselves by a steel mill-a disk of steel kept revolving in contact with a piece of flint: such an arrangement being safe, though certainly calculated to afford very little light. Davy found the means, by enclosing the flame in a kind of lantern of wire-gauze, of giving out light without inviting explosion. Armed with one of these lamps, Mr. Hodgson descended Hebburn pit, walked about in a terrible atmosphere of firedamp, or explosive gas, held his lamp high and low, and saw it become full of blazing gas without producing any explosion. He approached gradually a miner working by the spark light of a steel mill; a man who had not the slightest knowledge that such a wonder as the new lamp was in existence. No notice had been given to the man of what was about to take place. He was alone in an atmosphere of great danger, 'in the midst of life or death,' when he saw a light approaching, apparently a candle burning openly, the effect of which he knew would be instant destruction to him and its bearer. His command was instantly, 'Put out the light!' The light came nearer and nearer. No regard was paid to his cries, which then became wild, mingled with imprecations against the comrade (for such he took Hodgson to be) who was tempting death in so rash and certain a way. Still, not one word was said in reply; the light continued to approach, and then oaths were turned into prayers that his request might be granted; until there stood before him, silently exulting in his success, a grave and thoughtful man, a man whom he well knew and respected, holding up in his sight, with a gentle smile, the triumph of science, the future safe-guard of the pitmen. The clergyman afterwards acknowledged that he had done wrong in subjecting this poor fellow to so terrible a trial. Great and frequent as had been the calamities arising from firedamp, it was not till after an unusually destructive explosion in 1812, that any concentrated effort was made to obtain from science the means of neutralising it. In August 1815, Sir Humphry Davy was travelling through Northumberland. In consequence of his notable discoveries in chemistry, Dr. Gray, rector of Bishopwearmouth, begged him to make a short sojourn in Newcastle, and see whether he could suggest anything to cure the great danger of the mines. Mr. Hodgson and Mr. Buddle, the latter an eminent colliery engineer, explained all the facts to Davy, and set his acute mind thinking. He came to London, and made a series of experiments. He found that flame will not pass through minute tubes; he considered that a sheet of wire-gauze may be regarded as a series of little tubes placed side by side; and he formed a plan for encircling the flame of a lamp with a cylinder of such gauze. Inflammable air can get through the meshes to reach the flame, but it cannot emerge again in the form of flame, to ignite the rest of the air in the mine. He sent to Mr. Hodgson for a bottle of fire-damp: and with this he justified the results to which his reasoning had led him. At length, at the end of October, Davy wrote to Hodgson, telling all that he had done and reasoned upon, and that he intended to have a rough 'safety lamp' made. This letter was made public at a meeting in Newcastle on the 3rd of November; and soon afterwards Davy read to the Royal Society, and published in the Philosophical Trans-actions, those researches in flames which have contributed so much to his reputation. There can be no question that his invention of the safety lamp was due to his love of science and his wish to do good. He made the best lamp he could, and sent it to Mr. Hodgson, and read with intense interest that gentleman's account of the eventful experiences of the 9th of January. It is pleasant to know that that identical lamp is pre-served in the Museum of Practical Geology in Jermyn Street. Mr. Buddle advised Sir Humphry to take out a patent for his invention, which he was certain would realise £5000 to £10,000 a year. But Davy would have none of this; he did not want to be paid for saving miners' lives. 'It might,' he replied, 'undoubtedly enable me to put four horses to my carriage; but what could it avail me to have it said that Sir Humphry drives his carriage and four?' While the illustrious philosopher was thus effecting his philanthropic design by a strictly scientific course, a person then of little note, but afterwards the equal of Davy in fame,-George Stephenson, engine-wright at Killingworth Colliery, near Newcastle,-was taxing his extra-ordinary genius to effect a similar object by means more strictly mechanical. In August 1815, he devised a safety lamp, which was tried with success on the subsequent 21st of October. Accompanied by his son Robert, then a boy, and Mr. Nicholas Wood, a superintendent at Killingworth, Stephenson that evening descended into the mine. 'Advancing alone, with his yet untried lamp, in the depths of those underground workings-calmly venturing his own life in the determination to discover a mode by which the lives of many might be saved and death disarmed in these fatal caverns-he presented an example of intrepid nerve and manly courage, more noble even than that which, in the excitement of battle and the impetuosity of a charge, carries a man up to the cannon's mouth. Advancing to the place of danger, and entering within the fouled air, his lighted lamp in hand, Stephenson held it firmly out, in the full current of the blower, and within a few inches of its mouth. Thus exposed, the flame of the lamp at first increased, and then flickered and went out; but there was no explosion of gas. . . Such was the result of the first experiment with the first practical miner's safety lamp; and such the daring resolution of its inventor in testing its valuable qualities!' Stephenson's first idea was that, if he could establish a current within his lamp, by a chimney at its top, the gas would not take fire at the top of the chimney; he was gradually led to connect with this idea, an arrangement by a number of small tubes for admitting the air below, and a third lamp, so constructed-being a very near approach to Davy's plan-was tried in the Killingworth pit on the 30th of November, where to this day lamps constructed on that principle-and named the 'Geordy'-are in regular use. No one can now doubt that both Davy and Stephenson really invented the safety lamp, quite independently of each other: both adopted the same principle, but applied it differently. To this day some of the miners prefer the 'Geordy;' others give their vote for the ' Davy; ' while others again approve of lamps of later construction, the result of a combination of improvements. In those days, however, the case was very different. A fierce lamp-war raged throughout 1816 and 1817. The friends of each party accused the other of stealing fame. Davy having the advantage of an established reputation, nearly all the men of science sided with him. They affected superb disdain for the new claimant, George Stephenson, whose name they had never before heard. Dr. Paris, in his Life of Davy, says: 'It will hereafter be scarcely believed that an invention so eminently philosophic, and which could never have been derived but from the sterling treasury of science, should have been claimed on behalf of an engine-wright of Killingworth, of the name of Stephenson-a person not even professing a knowledge of the elements of chemistry.' There were others, chiefly men of the district, who de-fended the rights of the ingenious engine-wright, whose modesty, however, prevented him from ever taking up an offensive position towards his illustrious rival. MARRIAGE OF MR. ABERNETHYJanuary 9, 1800,Mr. Abernethy, the eccentric surgeon, was married to Miss Ann Threlfall. 'One circumstance on the occasion was very characteristic of him; namely, his not allowing it to interrupt, even for a day, his course of lectures at the hospital. Many years after this, I met him coming into the hospital one day, a little before two (the hour of lecture), and seeing him rather smartly dressed, with a white waistcoat, I said, 'You are very gay today, sir?' 'Ay,' said he; 'one of the girls was married this morning.' 'Indeed, sir,' I said. 'You should have given yourself a holiday on such an occasion, and not come down to the lecture.' 'Nay,' returned he; 'egad! I came down to lecture the day I was married myself!' On another occasion, I recollect his being sent for to a case just before lecture. The ease was close in the neighbourhood, and it being a question of time, he hesitated a little; but being pressed to go, he started off. He had, however, hardly passed the gates of the hospital before the clock struck two, when, all at once, he said: 'No, I'll be - if I do! ' and returned to the lecture-room.'-Macilvaia's Memoirs of Abernethy. |