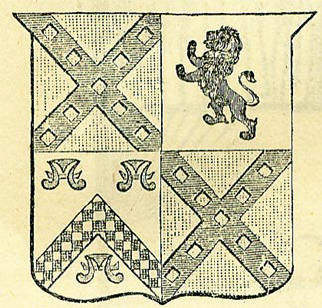

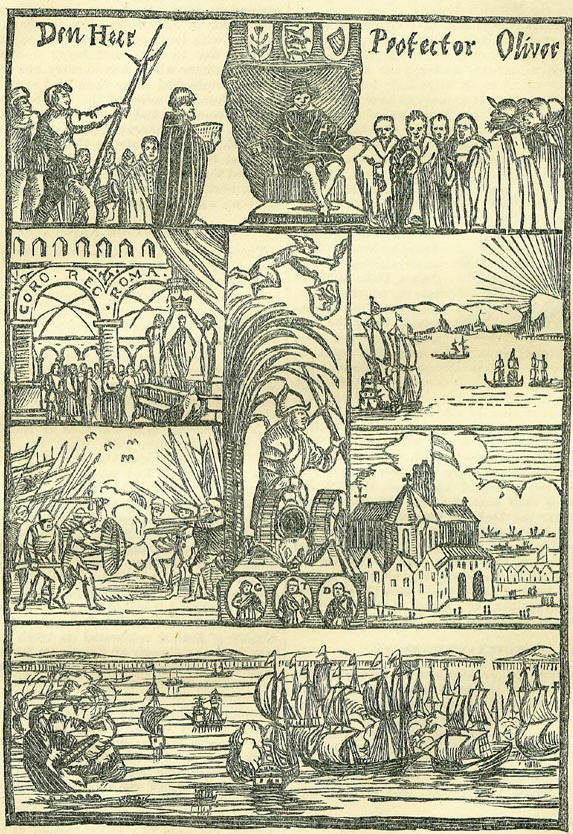

8th JanuaryDied: Galileo Galilei, 1642; John Earl of Stair, 1707; Sir Thomas Burnet, 1753; John Baskerville, printer, 1775; Sir William Draper, 1787; Lieutenant Thomas Waghorn, 1850. Feast Day: St. Apollinaris, the apologist, bishop, 175; St. Lucian, of Beauvais, martyr, 290; St. Nathalan, bishop, confessor, 452; St. Severinns, abbot, 482; St. Gudula, virgin, 712; St. Pega, virgin, about 719; St. Vulsiu, bishop, confessor, 973. ST. GUIDULAIs regarded with veneration by Roman Catholics as the patroness-saint of the city of Brussels. She was of noble birth, her mother having been niece to the eldest of the Pt-pins, who was Maire of the Palace to Dagobert I. Her father was Count Witger. She was educated at Nivelle, under the care of her cousin Ste Gertrude, after whose death in 664, she returned to her father's castle, and dedicated her life to the service of religion. She spent her future years in prayer and abstinence. Her revenues were expended on the poor. It is related of her, that going early one morning to the church of St. Morgelle, two miles from her father's mansion, with a female servant bearing a lantern, the wax taper havingbeen accidentally extinguished, she lighted it again by the efficacy of her prayers. Hence she is usually represented in pictures with a lantern. She died January 8th, 712, and was buried at Ham, near Villevord. Her relics were transferred to Brussels in 978, and deposited in the church of St. Gery, but in 1047 were removed to the collegiate church of Michael, since named after her the cathedral of St. Gudula. This ancient Gothic structure, commenced in 1010, still continues to be one of the architectural ornaments of the city of Brussels. Her Life was written by Hubert of Brabant not long after the removal of her relics to the church of St. Michael. GALILEO GALILEISuch (though little known) was the real full name of the famous Italian professor, who first framed and used a telescope for the observation of the heavenly bodies, and who may be said to have first given stability and force to the theory which places the sun in the center of the planetary system. In April or May 1609, Galileo heard at Venice of a little tubular instrument lately made by one Hans Lippershey of Middleburg, which made distant objects appear nearer, and he immediately applied himself to experimenting on the means by which such an instrument could be produced. Procuring a couple of spectacle glasses, each plain on one side, but one convex and the second concave on the other side, he put these at the different ends of a tube, and applying his eye to the concave glass, found that objects were magnified three times, and brought apparently nearer. Soon afterwards, having made one which could magnify thirty times, Galileo commenced observations on the surface of the moon, which he discovered to be irregular, like that of the earth, and on Jupiter, which, in January 1610, he ascertained to be attended by four stars, as he called them, which after-wards proved to be its satellites. To us, who calmly live in the knowledge of so much that the telescope has given us, it is inconceivable with what wonder and excitement the first discoveries of the rude tube of Galileo were received. The first effects to himself were such as left him nothing to desire; for, by the liberality of his patron, the Grand Duke of Tuscany, he was endowed with a high salary, independent of all his former professional duties. The world has been made well aware of the opposition which Galileo experienced from the ecclesiastical authorities of his age; but it is remarkable that the first resistance he met with came from men who were philosophers like himself. As he went on with his brilliant discoveries-the crescent form of Venus, the spots on the sun, the peculiar form of Saturn-he was met with a storm of angry opposition from the adherents of the old Aristotelian views; one of whom, Martin Horky, said he would 'never grant that Italian his new stars, though he should die for it.' The objections made by these persons were clearly and triumphantly refuted by Galileo: he appealed to their own senses for a sufficient refutation of their arguments. It was all in vain. The fact is equally certain and important that, while he gained the admiration of many men of high rank, he was an object of hostility to a vast number of his own order. It was not, after all, by anything like a general movement of the Church authorities that Galileo was brought to trouble for his doctrines. The Church had overlooked the innovations of Copernicus: many of its dignitaries were among the friends of Galileo. Perhaps, by a little discreet management, he might have escaped censure. He was, however, of an ardent disposition; and being assailed by a preacher in the pulpit, he was tempted to bring out a pamphlet defending his views, and in reality adding to the offence he had already given. He was consequently brought before the Inquisition at Rome, February 1615, and obliged to disavow all his doctrines, and solemnly engage never again to teach them. From this time, Galileo became manifestly less active in research, as if the humiliation had withered his, faculties. Many years after, recovering some degree of confidence, he ventured to publish an account of his System of the World, under the form of a dialogue, in which it was simply discussed by three persons in conversation. He had thought thus to escape active opposition; but he was mistaken. He had again to appear before the Inquisition, April 1633, to answer for the offence of publishing what all educated men now know to be true; and a condemnation of course followed. Clothed in sackcloth, the venerable sage fell upon his knees before the assembled cardinals, and, with his hands on the Bible, abjured the heresies he had taught regarding the earth's motion, and promised to repeat the seven penitential psalms weekly for the rest of his life. He was then conveyed to the prisons of the Inquisition, but not to be detained. The Church was satisfied with having brought the philosopher to a condemnation of his own opinions, and allowed him his liberty after only four days. The remaining years of the great astronomer were spent in comparative peace and obscurity. That the discoverer of truths so certain and so important should have been forced to abjure them to save his life, has ever since been a theme of lamentation for the friends of truth. It is held as a blot on the Romish Church that she persecuted 'the starry Galileo.' But the great difficulty as to all new and startling doctrines is to say whether they are entitled to respect. It certainly was not wonderful that the cardinals did not at once recognize the truth contained in the heliocentric theory, when so many so-called philosophers failed to recognize it. And it may be asked if, to this day, the promulgator of any new and startling doctrine is well treated, so long as it remains unsanctioned by general approbation, more especially if it appears in any degree or manner inconsistent with some point of religious doctrine. It is strongly to be suspected that many a man has spoken and written feelingly of the persecutors of Galileo, who daily acts in the same spirit towards other reformers of opinions, with perhaps less previous inquiry to justify him in what he is doing. JOHN, FIRST EARL OF STAIRThe Earl of Stair above cited was eldest son of James Dalrymple, Viscount Stair, the President of the Court of Session in Scotland, and the greatest lawyer whom that country has produced. This first earl, as Sir John Dalrymple, was one of three persons of importance chosen to offer the crown of Scotland to William and Mary at the Revolution. As Secretary of State for Scotland, he was the prime instrument in causing the Massacre of Glencoe, which covered his name with infamy, and did not leave that of his royal master untarnished. He was greatly instrumental in bringing about the union of Scotland with England, though he did not live to see it effected. His son, the second earl, as ambassador to France in the time of the regency of Orleans, was of immense service in defeating the intrigues of the Stuarts, and preserving the crown for the Hanover dynasty.  The remarkable talents and vigour of three generations of one family on the Whig side, not to speak of sundry offshoots of the tree in eminent official situations, rendered the Dalymples a vexation of no small magnitude to the Tory party in Scotland. It appears to have been with reference to them, that the Nine of Diamonds got the name of the Curse of Scotland; this card bearing a resemblance to the nine lozenges, or, arranged saltire-wise on their armorial coat. Various other reasons have, indeed, been suggested for this expression-as that, the game of Comète being introduced by Mary of Lorraine (alternatively by James, Duke of York) into the court at Holyrood, the Nine of Diamonds, being the winning card, got this name in consequence of the number of courtiers ruined by it; that in the game of Pope Joan, the Nino of Diamonds is the Pope-a personage whom the Scotch Presbyterians considered as a, curse; that diamonds imply royalty, and every ninth king of Scotland was a, curse to his country: all of them most lame and unsatisfactory suggestions, in comparison with the simple and obvious idea of a witty reference to a set of detested but powerful statesmen, through the medium of their coat of arms. Another supposition, that the Duke of Cumberland wrote his inhuman orders at Culloden on the back of the Nine of Diamonds, is negatived by the fact, that a caricature of the earlier date of October 21, 1715. represents the young chevalier attempting to lead a herd of bulls, laden with papal curses, excommunications, &c., across the Tweed, with the Nine of Diamonds lying before them. LIEUTENANT WAGHORNThis name will be permanently remembered in connection with the great improvements which have been made of late years in the postal communications between the distant parts of the British Empire and the home country. Waghorn was a man of extraordinary energy and resolution, as well as intelligence; and it is sad to think that his life was cut short at about fifty, before he had reaped the rewards due to his public services. In the old days of four-month passages round Cape Horn, a quick route for the Indian mail was generally felt as in the highest degree desirable. It came to be more so when the Australian colonies began to rise into importance. A passage by the Euphrates, and the 120 miles of desert between that river and the Mediterranean, was favourably thought of, was experimented upon, but soon abandoned. Waghorn then took up the plan of a passage by Egypt and the Red Sea, which, alter many difficulties, was at length realized in 1838. Such was his energy at this time, that, in one of his early journeys, when charged with important dispatches, coining one winter's day to Suez, and being disappointed of the steamer which was to carry him to Bombay, he embarked in an open boat to sail along the six hundred miles of the Red Sea, without chart or compass, and in six days accomplished the feat. A magnificent steam fleet was in time established on this route by the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company, and has, we need scarcely say, proved of infinite service in facilitating personal as well as postal communications with the East. BI-CENTENARY OF NEWSPAPERSThere are several newspapers in Europe which have lived two hundred years or more-papers that have appeared regularly, with few or no interruptions, amid wars, tumults, plagues, famines, commercial troubles, fires, disasters of innumerable kinds, national and. private. It is a grand thing to be able to point to a complete series of such a newspaper; for in it is to be found a record, however humble and imperfect, of the history of the world for that long period. The proprietors may well, make a holiday-festival of the day when such a bi-centenary is completed. A festival of this kind was held at Haarlem on the 8th of January, 1856, when the Haarlem Courant completed its 200th year of publication. The first number had appeared on the 8th of January, 1656, under the title of De Weekelyeke Courant van Europa; and a facsimile of this ancient number was produced, at some expense and trouble, for exhibition on the day of the festival. Lord Macaulay, when in Holland, made much use of the earlier numbers of this newspaper, for the purposes of his History. The first number contained simply two small folio pages of news. The Continent is rather rich in old newspapers of this kind. On the 1st of January, 1860, the Gazette of Rostock celebrated its 150th anniversary, and the Gazette of Leipsic its 200th. The proprietors of the latter paper distributed to their subscribers, on this occasion, facsimiles of two old numbers, of Jan. 1, 1660, and Jan. 1, 1760, representing the old typographical appearance as nearly as they could. It has lately been said that Russian newspapers go back to the year 1703, when one was established which Peter the Great helped both to edit and to correct in proof. Some of the proof sheets are still extant, with Peter's own corrections in the margin. The Imperial Library at St Petersburg is said to contain the only two known copies of the first year complete. The Hollandsclae Mercurius was issued more than two centuries ago, a small quarto exactly in size like our Notes and Queries; we can there see how the news of our civil war was from time to time received among the people of Holland, who were generally well affected to the royalist cause. At the assumption of power by Cromwell in 1653, the paper hoisted a wood-cut title representing various English matters, including Cromwell seated in council; and this, as an historical curiosity, we have caused to be here reproduced. In the original, there is a copy of verses by some Dutch poet, describing the subjects of the various designs on this carved page. He tells us that the doors of Westminster were opened to Oliver; that both the council and the camp bowed to him; and that London, frantic with joy, solicited his good services in connection with peace and commerce. The Hollandsche Merencius was, after all, a sort of Dutch 'Annual Register,' rather than a newspaper: there are many such in various countries, much more than 200 years old. Old newspapers have been met with, printed at Nurnberg in 1571, at Dillingen in 1569, at Ratisbon in 1528, and at Vienna even so early as 1524. There may be others earlier than this, for aught that is at present known.  Modern investigators of this subject, however, have found it previously necessary to agree upon an answer to the question, 'What is a newspaper?' Many small sheets were issued in old days, each containing an account of some one event, but having neither a preceding nor a following number under the same title. If it, be agreed that the word 'newspaper' shall be applied only to a publication-which has the following characteristics -a treatment of news from various parts of the world, a common title for every issue, a series of numbers applied to them all, a date to each number, and a regular period between the issues -then multitudes of old publications which have hitherto been called newspapers must be expelled from the list. It matters not what we call them, provided there be a general agreement as to the scope of the word used. A very unkind blow was administered to our national vanity somewhat more than twenty years ago. We fancied we possessed in our great National Library at the British Museum, a real printed English newspaper, two centuries and a half old. Among the Sloane MSS. is a volume containing what purport to he three numbers of the English Mercuric, a newspaper published in 1588: they profess to be Nos. 50, 51, and 54 of a series: and they give numerous particulars of the Spanish Armada, a subject of absorbing interest in those days. Each number consists of four pages somewhat shorter and broader than that which the reader now holds in his hand. Where they had remained for two centuries nobody knew; but they began to be talked about at the close of the last century-first in Chalmers' Life of Ruddiman, then in the Gentleman's Magazine, then in Nichols' Literary Anecdotes, then in D'Israeli's Curiosities of Literature, then in the English edition of Beckmann, then in various English and Foreign Cyclopædias, and then, of course, in cheap popular periodicals. So the public faith remained firm that the English Mercuric was the earliest English newspaper. The fair edifice was, however, thrown down in 1839. Mr. Thomas Watts, the able Assistant Librarian at the British Museum, on subjecting the sheets to a critical examination, found abundant evidence that the theory of their antiquity was not tenable. Manuscript copies of three numbers are bound up in the same volume; and from a scrutiny of the paper, the ink, the handwriting, the type (which he recognised as belonging to the Caslon foundry), the literary style, the spelling, the blunders in fact and in date, and the corrections, Mr. Watts came to a conclusion that the so-called English Mercuric was printed in the latter half of the last century. The evidence in support of this opinion was collected in a letter addressed to Mr. Panizzi, afterwards printed for private circulation, Eleven years later, in 1850, Mr. Watts furnished to the Gentleman's Magazine the reasons which led him to think that the fraud had been perpetrated by Philip Yorke, second Earl of Hardwicke: in other words, that the Earl, for some purpose not now easy to surmise, had written certain paragraphs in a seemingly Elizabethan style, and caused them to be printed as if belonging to a newspaper of 1588. Be this as it may, concerning the identity of the writer, all who now look at the written and printed sheets agree that they are not what they profess to be; and thus a pretty bit of national complacency is set aside; for we have become ashamed of our English Mercurie. Mr. Knight Hunt, in his Fourth Estate, gives us credit, however, for a printed newspaper considerably more than two centuries old. He says: 'There is now no reason to doubt that the puny ancestor of the myriads of broad sheets of our time was published in 1622; and that the most prominent of the ingenious speculators who offered the novelty to the world was Nathaniel Butter. His companions in the work appear to have been Nicholas Bourne, Thomas Archer, Nathaniel Newberry, William Sheppard, Bartholomew Donner, and Edward Allde. All these different names appear in the imprint of the early numbers of the first newspaper, the Weekly News. What appears to be the earliest sheet boars the date 23rd of May 1622.' About 1663, there was a newspaper called Kingdom's Intelligencer, more general and useful than any of its predecessors. Sir Roger L'Estrange was connected with it; but the publication ceased when the London Gazette (first called the Oxford Gazette) was commenced in 1665. A few years before this, during the stormy times of the Commonwealth, newspapers were amazingly numerous in England; the chief writers in them being Sir John Birkenhead and Marchmont Needham. If it were any part of our purpose here to mention the names of newspapers which have existed for a longer period than one century and a half, we should have to make out a pretty large list. Claims have been put forward in this respect for the Lincoln, Rutland, and Stamford Mercury, the Scotch Postman, the Scotch Mercury, the Dublin News-Letter, the Dublin Gazette, Puc's Occurrences, Faullener's Journal, and many others, some still existing, others extinct. The Edinburgh Evening Courant has, we believe, never ceased to appear thrice a week (latterly daily) since the 15th of December 1718; and its rival, the Caledonian Mercury, is but by two years less venerable. Saunders's News-Letter has had a vitality in Dublin of one hundred and eighteen years, during eighty of which it has been a daily paper. In connection with these old newspapers, it is curious to observe the original meaning of the terms Gazette and News-Letter. During the war between the Venetians and the Turks in 1563, the Venetian Government, being desirous of communicating news on public affairs to the people, caused sheets of military and commercial intelligence to be written: these sheets were read out publicly at certain places, and the fee paid for hearing them was a small coin called a gazzetta. By degrees, the name of the coin was transferred to the written sheet; and an official or government newspaper became known as a Gazzetta or Gazetta. For some time afterwards, the Venetian Government continued the practice, sending several written copies to several towns, where they were read to those who chose to listen to them. This rude system, however, was not calculated to be of long duration: the printing-press speedily superseded such written sheets. The name. however, survives; the official newspapers of several European countries being called Gazettes. Concerning News-Letters, they were the pre-cursors of newspapers generally. They were really letters, written on sheets of writing-paper. Long after the invention of printing, readers were too few in number to pay for the issue of a regular periodically-printed newspaper. How, then, could the wealthy obtain information of what was going on in the world? By written newspapers or news-letters, for which they paid a high price. There were two classes of news-writers in those days-such as wrote privately to some particular person or family, and such as wrote as many copies as they could dispose of. Whitaker, in his History of Craven, says that the Clifford family preserves a record or memorandum to the following effect: 'To Captain Robinson, by my Lord's commands, for writing letters of newes to his Lordship for half a year, five pounds.' In or about the year 1711, the town-council of Glasgow kept a news-writer for a weekly 'letter.' A collection of such letters was afterwards found in Glammis Castle. During the time of Ben Jonson, and down to a later period, there were many news-writers living in London, some of them unemployed military men, who sought about in every quarter for news. Some would visit the vicinity of the Court, some the Exchange, some Westminster Hall, some (old) St Paul's-the nave of which was, in those days, a famous resort for gossips. All that they could pick up was carried to certain offices, where they or other writers digested the news, and made it sufficient to fill a sheet of certain size. The number of conies of this sheet depended on the number of subscribers, most of whom were wealthy families residing in the country. Ben Jonson frequently satirizes these news-writers, on account of the unscrupulous way in which the news was often collected. Even in the days of Queen Anne, when mails and posts were more numerous, and when the printing-press had superseded the written news-letter, the caterers for the public were often suspected of manufacturing the news which they gave. Steele, in No, 42 of the Taller, represents a news-writer as excusing him-self and his craft in the following way: Hard shifts we intelligencers are forced to. Our readers ought to excuse us, if a westerly wind, blowing for a fortnight together, generally fills every paper with an order of battle; when we shew our mental skill in every line, and according to the space we have to fill, range our men in squadrons and battalions, or draw out company by company, and troop by troop: ever observing that no muster is to be made but when the wind is in a cross-point, which often happens at the end of a campaign, when half the men are deserted or killed. The Courant is sometimes ten deep, his ranks close; the Postboy is generally in files, for greater exactness; and the Postman comes down upon you rather after the Turkish way, sword in hand, pell-mell, without form or discipline; but sure to bring men enough into the field; and wherever they are raised, never to lose a battle for want of numbers.' GETTING INTO A SCRAPEThis phrase, involving the use of an English word in a sense quite different from the proper one, appears to be a mystery to English lexicographers. Todd, indeed, in his additions to Johnson, points to skrap, Swedish, and quotes from Lye, 'Draga en in i scraeper-to draw any one into difficulties.' But it may be asked, what is the derivation of the Swedish phrase? It is as likely that the Swedes have adopted our phrase as that we have adopted theirs. It may be suspected that the phrase is one of those which are puzzling in consequence of their having originated in special local circumstances, or from some remarkable occurrence. There is a game called golf, almost peculiar to Scotland, though also frequently played upon Blackheath, involving the use of a small, hard, elastic ball, which is driven from point to point with a variety of wooden and iron clubs. In the north, it is played for the most part upon downs (or links) near the sea, where there is usually abundance of rabbits. One of the troubles of the golf-player is the little hole which the rabbit makes in the sward, in its first efforts at a burrow; this is commonly called a rabbit's scrape, or simply a scrape. When the ball gets into a scrape, it can scarcely be played. The rules of most golfing fraternities, accordingly, include one indicating what is allowable to the player when he gets into a scrape. Here, and here alone, as far as is known to the writer, has the phrase a direct and intelligible meaning. It seems, therefore, allowable to surmise that this phrase has originated amongst the golfing societies of the north, and in time spread to the rest of the public. |