7th FebruaryBorn: Rev. Sir Henry Mournieff, D.D, 1750; Charles Dickens, novelist, 1812. Died: James Earl of Moray (the Bonny), murdered 1592; Dr. Bedell, bishop of Icilmore, 1642; Anne Radcliffe, novelist, 1823, Pimlico; Henry Neck, poet, 1828, London; M. Bourrienne, formerly Secretary to Napoleon Bonaparte, died in a madhouse at Caen, Ncrmandli, 1834. Feast Day: St. Theodorus (Stratilates), martyred at Heraclea, 319. St. Augulus, bishop of London, martyr, 4th century. St. Tresain, of Ireland, 6th century. St. Richard, king of the West Saxons, circ. 722. St. Romualdo, founder of the order of Camaldoli, 1027. ST. ROMUALDORomualdo was impelled to a religious life by seeing his father in a fit of passion commit man-slaughter. Assuming the order of St. Benedict, he was soon scandalised by the licentious lives generally led by his brethren, and to their reformation he zealously devoted himself. The result was his forming a sub-order, styled from the place of its first settlement, the Camaldolesi, who, in their asceticism and habits of solemn and silent contemplation, remind us of the early Egyptian anchorets. St. Romualdo, who died at an advanced age in 1027, was consequently held in great veneration, and Dante has placed him in his Paradise, 'among the spirits of men contemplative.' MRS. RADCLIFFE'S ROMANCESThis admirable writer had, in her youth, the benefit of the society of Mr. Bentley, the well-known man of letters and taste in the arts, and of Mr. Wedgwood, the able chemist; and she became thus early introduced to Mrs. Montague, Mrs. Piozzi, and the Athenian Stuart. Her maiden name was Ward, and she acquired that which made her so famous by marrying Mr. William Radcliffe, a graduate at Oxford and a student at law, afterwards proprietor and editor of the English Chronicle. Her first work was a romance styled The Castles of Atlalin and Dunbseyne; her second, which appeared in 1790, The Sicilian Romance, of which Sir Walter Scott, then a novel reader of no ordinary appetite, says: 'The scenes were inartificially connected, and the characters hastily sketched, without any attempt at individual distinction; being cast in the mould of ardent lovers, tyrannical parents, with domestic ruffians, guards, and others, who had wept or stormed through the chapters of romance, without much alteration in their family habits or features, for a quarter of a century before Mrs. Radcliffe's time.' Nevertheless, 'the praise may be claimed for Mrs. Radcliffe, of having been the first to introduce into her prose fictions a beautiful and fanciful tone of natural description and impressive narrative, which had hitherto been exclusively applied to poetry.' The Romance of the Forest, which appeared in 1791, placed the author at once in that rank and preeminence in her own particular style of composition, which she ever after maintained. Next year, after visiting the scenery of the Rhine, Mrs. Radcliffe is supposed to have written her Mysteries of Udolpho, or, at least, corrected it, after the journey. For the Mysteries, Mrs. Radcliffe received the then unprecedented sum of £500; for her next production, the Italian, £800. This was the last work published in her lifetime. This silence was unexplained: it was said that, in consequence of brooding over the terrors which she had depicted, her reason had been overturned, and that the author of the Mysteries of Udolpho only existed as the melancholy inmate of a private madhouse; but there was not the slightest foundation for this unpleasing rumor. Of the author of the Mysteries of Udolpho, the unknown author of the Pursuits of Literature spoke as 'a mighty magician, bred and surrounded by the Florentine muses in their secret solitary caverns, amid the paler shrines of Gothic superstition, and in all the dreariness of enchantment.' Dr. Joseph Warton, the head master of Winchester School, then at a very advanced period of life, told Robinson, the publisher, that, happening to take up the Mysteries of Udolpho, he was so fascinated that he could not go to bed until he had finished it, and that he actually sat up a great part of the night for that purpose. Mr. Sheridan and Mr. Fox also spoke of the Mysteries with high praise. The great notoriety attained by Mrs. Radcliffe's romances in her lifetime, made her the subject of continually recurring rumours of the most absurd and groundless character. One was to the effect that, having visited the fine old Gothic mansion of Haddon Hall, she insisted on remaining a night there, in the course of which she was inspired with all that enthusiasm for hidden passages and mouldering walls which marks her writings. The truth is, that the lady never saw Haddon Hall. Mrs. Radcliffe died in Stafford-row, Pimlico, February 7th, 1823, in her fifty-ninth year; and was buried in the vault of the chapel, in the Bayswater-road, belonging to the parish of St. George, Hanover-square. THE GREAT BED OF WARE

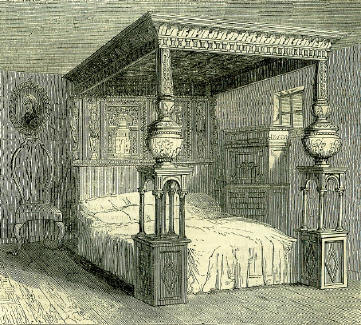

When Sir Toby Belch (Twelfth Night, Act iii., scene 2) wickedly urges Aguecheek to pen a challenge to his supposed rival, he tells him to put as many lies in a sheet as will lie in it, 'although the sheet were big enough for the bed of Ware in England.' The enormous bed here alluded to was a wonder of the age of Shakspeare, 'antique furniture. It is believed to be not older and it still exists in Ware. It is a square of 10 than Elizabeth's reign. It has for ages been an feet 9 inches, 7 feet 6 inches in height, very inn wonder, visited by multitudes, and described elegantly carved, and altogether a fine piece of by many travellers. There are strange stories people engaging it to lie in, twelve at a time, by way of putting its enormous capacity for accommodation to the proof. It was long ago customary for a company, on seeing it, to drink from a can of beer a toast appropriate to it. In the same room, there hung a pair of horns, upon which all new-comers were sworn, as at Highgate. THE PORTLAND VASEIn one of the small rooms of the old British Museum (Montague House), there had been exhibited, for many years, that celebrated production of ceramic art-the Portland Vase; when, on the 7th of February 1845, this beautiful work was wantonly dashed to pieces by one of the visitors to the Museum, named William Lloyd. The Portland Vase was found about the year 1560, in a sarcophagus in a sepulchre under the Monte del Grano, two miles and a half from Rome. It was deposited in the palace of the Barberini family until 1770, when it was purchased by Byres, the antiquary, who subsequently sold it to Sir William Hamilton. From Sir William it was bought for 1800 guineas, by the Duchess of Portland; and at the sale of her Grace's property, after her decease, the Vase was bought in by the Portland family for £1029. The Vase is 91 inches high, and 7; inches in diameter, and has two handles. Four authors of note considered it to be stone, but all differing as to the kind of stone: Breval regarded it as chalcedony; Bartoli, sardonyx; Count Tetzi, amethyst; and De La Chausse, agate. In reality it is composed of glass, ornamented with white opaque figures, upon a dark-blue semi-transparent ground; the whole having been originally covered with white enamel, out of which the figures have been cut after the manner of a cameo. The glass foot is thought to have been cemented on, after bones or ashes had been placed in the vase. This mode of its manufacture was discovered by examination of the fractured pieces, after the breaking of the vase in 1845; a drawing of the pieces is preserved in the British Museum. The subject of the figures is involved in mystery; for as much difference of opinion exists respecting it as formerly did regarding the materials of the vase. The seven figures, each five inches high, are said by some to illustrate the fable of Thaddeus and Theseus; Bartoli supposed the group to represent Proserpine and Pluto; Count Tetzi, that it had reference to the birth of Alexander Severus, whose cinerary urn it is thought to be; whilst the late Mr. Thomas Winans, F.S.A., considered the design as representing a lady of quality consulting Galen, who at length discovered her sickness to be love for a celebrated rope-dancer. The vase was engraved by Cipriani and Bartolozzi, in 1786. Copies of it were executed by Wedgwood at fifty guineas each; the model having cost 500 guineas. Sir Joseph Banks and Sir Joshua Reynolds bore testimony to the excellent execution of these copies, which were chased by a steel rifle, after the bas-relief had been wholly or partially fired. One of these copies may be seen in the British Museum. The person who so wantonly broke the original vase was sentenced to pay a fine, or to undergo imprisonment; and the sum was paid by a gentleman, anonymously. The pieces, being gathered up, were afterwards put together by Mr. Doubleday, so perfectly, that a blemish can scarcely be detected; and the restored Vase is now kept in the Medal-room of the Museum. |