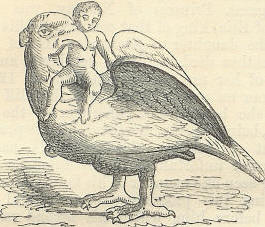

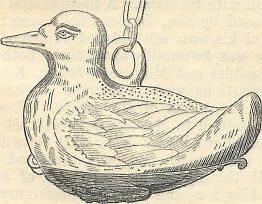

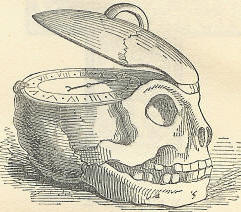

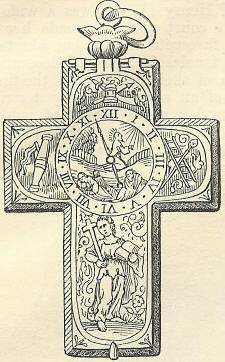

6th OctoberBorn: Edward V of England, 1470; Dr. John Key (Caius), founder of Caine College, Cambridge, 1510, Norwich; Dr. Nevil Maskelyne, astronomer, 1732, London; Madame Campan, biographer of Marie Antoinette, 1752, Paris; Louis Philippe, king of France, 1773, Paris; Madame Jenny Lind Goldschmidt, vocalist, 1821, Stockholm. Died: Charles the Bald, king of France, 877; Charles X, king of France, 1836, Goritz, Styria. Feast Day: St. Faith or Fides, virgin, and her companions, martyrs, 4th century. St. Bruno, confessor, founder of the Carthusian monks, 1101. ANCIENT WATCHESMany inventions of the greatest value, and ultimately of the commonest use, are sometimes the most difficult to trace to their origin. It is so with clocks and watches. Neither the precise year of their invention, nor the names of their inventors, can be confidently stated. Till the close of the tenth century, no other mode of measuring time than by the sun-dial, or the hour-glass, appears to have existed; and then we first hear of a graduated mechanism adapted to the purpose, this invention being usually ascribed to the monk Gerbert, who was raised to the tiara in 999, under the name of Sylvester II. These clocks were cumbrous machines; and it is not till the fourteenth century that we hear of portable clocks. In the succeeding century, they were much more common, and were part of the necessary furniture of a better-class house. They were hung to the walls, and their movements regulated by weights and lines, like the cheap kitchen-clocks of the present day. The invention of the spiral spring as the motive power, in place of the weight and line, gave, about the middle of the fifteenth century, the first great impetus to improvement, which now went on rapidly, and resulted in the invention of the watch a time measurer that might be carried about the person. Southern Germany appears to have been the place from whence these welcome novelties chiefly issued; and the earliest watches were known as 'Nuremberg Eggs,' a sobriquet obtained as well from the city from whence they emanated, as from their appearance. The works were enclosed in circular metal cases, and as they hung from the girdle, suggested the idea of an egg. Before the invention, or general adoption of the fusee-that is, from about 1500 to 1540 the movements were entirely of steel; then brass was adopted for the plates and pillars, the wheels and pinions only being fabricated of steel; and ultimately the pinions only were of steel. The fusee being universally adopted about 1540, no great change occurred for fifty years, during which time the silversmith seems to have assisted the watchmaker in the production of quaint cases for his works, so that they might become ornamental adjuncts to a lady's waist. Our first example (formerly in the Bernal Collection, and now in that of Lady O. Fitzgerald) tells, after an odd fashion, the classic tale of Jupiter and Ganymede.  The works are contained in the body of the eagle, which opens across the centre, and displays the dial-plate, richly engraved with scrolls and flowers on a ground of niello. It will be perceived that this watch is so constructed, that when not suspended to the girdle by the ring in the centre of the bird's back, it can stand on the claws wherever its owner may choose to place it. Watches were now made of all imaginable shapes and sizes, and the cases of all forms and materials; crystal was very commonly used, through which the mechanism of the watch might be observed. Sometimes stones of a more precious character were cut and adapted to the purpose. The Earl of Stamford possesses one small egg-shaped watch, the cases cut out of jacynths, the cover set round with diamonds on an enamelled border. Mr. O Morgan has in his curious collection of watches one in form of a golden acorn, which discharged a diminutive wheel-lock pistol at a certain hour; another was enclosed in silver cases, taking the form of cockle-shells.  We engrave a specimen of a watch in form of a duck (also in Lady O. Fitzgerald's collection); the feathers are chased on the silver. The lower part opens, and the dial-plate, which is likewise of silver, is encircled with a gilt ornamented design of floriated scrolls and angels' heads. The wheels work on small rubies. It is believed to be of the time of Queen Elizabeth. When the famous Diana of Poitiers became the mistress of Henry II, she was a widow, and the complaisant court not only made her mourning-colours the favourite fashion, but adopted the most lugubrious fancies for personal decoration.  Rings in the form of skeletons clasped the finger; other mementos of an equally ghastly description were used as jewels; small coffins of gold contained chased and enamelled figures of death; and watches were made in the form of skulls, of which we engrave an example. All these quaint and bizarre forms passed out of fashion at the early part of the seventeenth century, when watchmakers seem to have devoted their attention chiefly to the compact character of their work. About 1620, they assumed a flattened oval form, such as we have seen used to a comparatively recent period; they were sometimes furnished with astronomical dials, and perpetual moving calendars, and often struck the hour; the inner case acting as a silver bell. In Ben Jonson's Staple of News, the opening scene exhibits a dissolute junior anxiously awaiting his majority, who ' draws forth his watch, and sets it on the table;' immediately afterwards exclaiming: It strikes!-one, two, Three, four, five, six. Enough, enough, dear watch, Thy pulse hath beat enough. Now sleep and rest; Would thou couldst make the time to do so too: I'll wind thee up no more!  It appears, then, that until 1670, when the pendulum-spring was invented, the mechanism of the watch had made no advance since the days of Elizabeth. The French makers were among the first to introduce judicious improvements, particularly such as effected weight and size. Lady Fitzgerald possesses a gold enamelled watch manufactured by order of Louis XIII, as a present to our Charles I, which may rival a modern work in its smallness. It is oval; measuring about 2 inches by 1 1/2 across the face, and is an inch in thickness. The back is chased in high-relief with the figure of St. George conquering the dragon; the motto of the Garter surrounds the case, which is enriched with enamel colours. Grotesque forms for watch-cases seem to have quite gone out of fashion in the seventeenth century, with one exception; they were occasionally made in the form of a cross to hang at the girdle; and are consequently, but erroneously, sometimes called 'Abbess's watches.' The example here engraved is also from the collection just alluded to. It is covered with elaborate engraving of a very delicate character; the centre of the dial-plate represents Christ's agony in the Garden of Olives, the outer compartments being occupied by the emblems of his passion; a figure of Faith occupying the lowermost. The style of engraving is very like that of the famous Theodore de Dry, who worked largely for the French silversmiths at the commencement of the seventeenth century. |