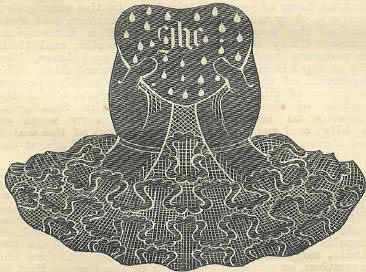

5th OctoberBorn: Jonathan Edwards, eminent Calvinistic divine, 1703, Windsor, Connecticut; Horace Walpole, Earl of Orford, celebrated virtuoso and man of letters, 1717, Wareham,, Dorsetshire;. Dr. William Wilkie, author of the Epigoniad, 1721, Dalmeny, Linlithgowshire; Lloyd, Lord Kenyon, distinguished lawyer, 1732, Greddington, Flintshire. Died: Justin, Roman emperor, 578; Henry III, emperor of Germany, 1056; Philip III, the Bold, king of France, 1285; Edward Bruce, brother of King Robert, killed at Fagher, Ireland, 1318; Augustus III, king of Poland, 1763, Dresden; Charles, Marquis Cornwallis, governor-general of India, 1805, Ghazepore, Benares; Bernard, Comte de Lacépdè, eminent naturalist, 1825. Feast Day: St. Placidus, abbot, and companions, martyrs, 546. St. Galla widow, about 550. HEART-BEQUESTSSome curious notions and practices respecting the human heart came into vogue about the time of the first Crusade, and were by many believed to have originated among those who died in that expedition. As the supposed seat of the affections, the heart was magnified into undue importance, and, after the death of a beloved or distinguished person, became the object of more solicitude than all the rest of his body. Thus the heart was considered the most valuable of all legacies, and it became the habit for a person to bequeath it to his dearest friend, or to his most favourite church, abbey, or locality, as a token of his supreme regard. And when no such bequest was made, the friends or admirers of deceased persons would cause their hearts to be carefully embalmed, and then, enclosing them in some costly casket, would preserve them as precious treasure, or entomb them with special honor. This remarkable practice, which has been continued more or less down to the present century, was most prevalent during the medieval ages-numerous instances of which are still on record, and many of them are curious and interesting. Our space will only permit us to give a few specimens: Robert, the famous Earl of Mellent and Leicester, died in 1118, in the abbey of Preaux, where his body was buried, but his heart, by his own order, was conveyed to the hospital at Brackley, to be there preserved in salt. He had been among the early Crusaders in the Holy Land, and was, says Henry of Huntingdon, 'the most sagacious in political affairs of all who lived between this and Jerusalem. His mind was enlightened, his eloquence persuasive, his shrewdness acute.' But he was rapacious, wily, and unscrupulous, and acquired much of his vast possessions, which were very extensive, both in England and Normandy, by unjust mancoeuvres, and acts of cruelty and violence. When he perceived death approaching, he assumed the monastic habit, the usual act of atonement in such characters at that period, and died a penitent in the abbey of Praeux, but, while he founded the hospital at Brackley, where his heart was preserved, he stoutly refused to restore any of the possessions which he had unjustly acquired. Isabella, daughter of William the Marshal, Earl of Pembroke, and wife of Richard, brother of Henry III, died at Berkhamstead in 1239, and ordered her heart to be sent in a silver cup to her brother, then abbot of Tewkesbury, to be there buried before the high-altar. Her body was buried at Beaulieu, in Hampshire. 'The noble Isabella, Countess of Gloucester and Cornwall,' says Matthew Paris, 'was taken dangerously ill of the yellow jaundice, and brought to the point of death. She became senseless, and after having had the ample tresses of her flaxen hair cut off, and made a full confession of her sins, she departed to the Lord, together with a boy to whom she had given birth. When Earl Richard, who had gone into Cornwall, heard of this event, he broke out into the most sorrowful lamentations, and mourned inconsolably.' Henry, their son, while attending mass in the church of St. Lawrence, at Viterbo, in Tuscany, was cruelly murdered by Simon De Monfort and Guy de Montfort, in revenge for the death of their father at the battle of Evesham, in which, however, he appears to have had no part. His heart was sent in a golden vase to Westminster Abbey, where it was deposited in the tomb of Edward the Confessor. On his monument was a gilt statue holding his heart, labeled with these words: 'I bequeath to my father my heart pierced with the dagger.' His father, Richard, king of the Romans, having been thrice married, died in 1272, from grief at his son's murder. His body was buried at the abbey of Hayles, his own foundation, and his heart was deposited in the church of the Minorite Brethren, at Oxford, under a costly pyramid erected by his widow. The heart of John Baliol, Lord of Barnard Castle, who died in 1269, was, by his widow's desire, embalmed and enclosed in an ivory casket richly enamelled with silver. His affectionate widow, Devorgilla, used to have this casket placed on the table every day when she ate her meals, and ordered it to be laid on her own heart, when she was herself placed in her tomb. She was buried, according to her own direction, near the altar in New Abbey, which she herself had founded in Galloway, and the casket containing her husband's heart placed on her bosom. From this touching incident, the abbey received the name of Dolce Cor, or Sweet-heart Abbey, and for its arms bore in chief a heart over two pastoral staffs, and in base three mullets of five points. Hearts were not only bequeathed by Crusaders, who died in the Holy Land, to their friends at home, in testimony of unaltered affection, but were sometimes sent there in fulfillment of an unaccomplished vow. Thus Edward I, after he ascended the throne, again took the cross, promising to return to Jerusalem, and give his best support to the crusade, which was then in a depressed condition. But, being detained by his wars with Scotland, unexpected death, in 1307, prevented the fulfilment of his engagement. He therefore, on his death-bed, charged his son to send his heart to Palestine, accompanied with a hundred and forty knights and their retinues, in discharge of his vow. Having provided two thousand pounds of silver for the support of this expedition, and I his heart being so conveyed thither, he trusted that God would accept this fulfilment of his vow, and grant his blessing on the undertaking: He also imprecated I eternal damnation on any who should expend the money for any other purpose. But the disobedient son little regarded the commandment of his father.' It is remarkable that the two sworn foes, Edward I of England, and Robert Bruce, king of Scotland, should have alike decided to send their hearts to be buried in the Holy Land. Each gave the order on his death-bed; each had the same motive for giving it; and the injunction of each was destined to be unperformed; but had their wishes been realised, the hearts of these two inveterate enemies would have met to rest quietly together for ever, in the same sepulchre. The account of Bruce's heart is very interesting. As he lay on his death-bed, in 1329, he entreated Sir James Douglas, his dear and trusty friend, to carry his heart to Jerusalem, because he had not, on account of his war with England, been able to fulfil a vow which he had made to assist in the crusade. Sir James, weeping exceedingly, vowed, on the honor of a knight, faithfully to discharge the trust reposed in him. After the king's death, his heart was taken from his body, embalmed, and enclosed in a silver case which, by a chain, Douglas suspended to his neck; and then, having provided a suitable retinue to attend him, he departed for the Holy Land. On reaching Spain, he found the king of Castile hotly engaged in war with the Moors, and thinking any contest with Saracens consistent with his vow, he joined the Spaniards in a battle against the Moors, but, ignorant of their mode of fighting, was soon surrounded by horsemen, so that escape was impossible. In desperation, he took the precious heart from his neck, and threw it before him, shouting aloud: 'Pass on as thou wort wont; I will follow or die!' He followed, and was immediately struck to the earth. His dead body was found after the battle, lying over the heart of Bruce. His body was carried away by his friends, and honorably buried in his own church of St. Bride, at Douglas. Bruce's heart was intrusted to the charge of Sir Simon Locard of Lee, who bore it back to Scotland, and deposited it beneath the altar in Melrose Abbey, where, perhaps, it still remains. From this incident, Sir Simon changed his name from Locard to Lockheart (as it used to be spelled), and bore in his arms a heart within a fetterlock, with the motto, 'Corda serrata pando.' From the same incident, the Douglases bear a human heart, imperially crowned, and have in their possession an ancient sword, emblazoned with two hands holding a heart, and dated 1329, the year in which Bruce died. An old ballad, quoted in the notes to Scott's Marmion, has this stanza I will ye charge, efter gat I depart, To holy grave, and thair bury my hart; Let it remain ever bothe tyme and howr, To ye last day I see my Savior. Mrs. Hemans has some beautiful lines on Bruce's heart, in Melrose Abbey, of which the following is the first stanza: Heart! that didst press forward still, Where the trumpet's note rang shrill, Where the knightly swords were crossing, And the plumes like sea-foam tossing; Leader of the charging spear, Fiery heart!-and liest thou here? May this narrow spot inurn Aught that so could beat and burn? Sir Robert Peckham, who died abroad, caused his heart to be sent into England, and buried in his family vault at Denham, in Buckinghamshire. He died in 1569, but his heart appears to have remained for many years unburied, as we gather from the following entry in the parish-register of burials: Edmund us Peckham, Esgr., sonne of Sir George Peckham, July 18, 1586. On the same day was the harte Of Sr Robert Peckham, knight, buried in the vault under the chappell.' The heart is enclosed in a leaden case thus inscribed: 'J. H. S. Robertus Peckham Eques Auratus Anglus Cor suum Dulciss. patrie major. Monumentis commendari. Obiit 1 SeptembrisMD. XIX.' Edward Lord Windsor, of Bradenham, Bucks, who died at Spa, January 24, 1574, bequeathed his body to be buried in the cathedral church of the noble city of Liege, with a convenient tomb to his memory, but his heart to be enclosed in lead, and sent into England, there to be buried in the chapel at Bradenham, under his father's tomb, in token of a true Englishman.' The case containing this heart, which has on it a long inscription, is still in the vault at Bradenham, and was seen in 1848, when Isaac d'Israeli was buried in the same vault. The circumstances respecting the heart of Lord Edward Bruce, who was killed in a duel in 1613, are interesting. His body was interred at Bergen, in Holland, where he died, and a monument was there erected to his memory. But a tradition remained in his family, that his heart had been conveyed to Scotland, and deposited in the burial-ground adjoining the old Abbey-Church of Culross, in Perthshire. The tradition had become to many a discredited tale, when, to put it to the test, a search was made in 1806 for the precious relic. Two flat stones, strongly clasped together with iron, were discovered about two feet below the level of the pavement, and partly under an old projection in the wall.  These stones had on them no inscription, but the singularity of their being thus braced together, induced the searchers to separate them, when a silver case, shaped like a heart, was found in a cavity between the stones. The case, which was engraved with the arms and name of Lord Edward Bruce, had hinges and clasps, and on being opened, was found to contain a heart carefully embalmed in a brownish coloured liquid. After drawings of it were taken, it was carefully replaced in its former situation. In another cavity in the stones was a small leaden box, which had probably contained the bowels, but if so, they had then become dust. It may be noticed in passing, as another proof of the undue importance attributed to the heart, that formerly the executioner of a traitor was required to remove the body from the gallows before life was extinct, and plucking out the heart, to hold it up in his hands, and exclaim aloud, 'Here is the heart of a traitor!' 'It was currently reported,' says Anthony Wood, 'that when the executioner held up the heart of Sir Everard Digby, and said, 'Here is the heart of a traitor!' Sir Everard made answer and said, 'Thou liest!' 'This story, which rests solely on Wood's authority, is generally discredited, though Lord Bacon affirms there are instances of persons saying two or three words in similar cases. From attaching such importance to the human heart, doubtless arose the practice, which is exemplified in many of our churches, of representing it so freely in sepulchral commemoration. And this occurs, not only where a heart alone is buried, but often the figure of a heart with an inscription is adopted as the sole memorial over the remains of the whole body. An example may be seen in St. John's Church, Margate, Kent (see engraving on the previous page). A plate of brass, cut into the shape and size of a human heart, is sunk into the slab which covers the remains of a former vicar of the church. The heart is inscribed with the words 'Credo q',' which begin each inscription on three scrolls that issue from the heart, thus: Redemptor meus vivit credo qd De terra surrecturus sum In carne mea videbo demun Salvatorem meum. Beneath the heart is a Latin inscription, which shews that the whole body of the deceased was interred below. In English it is as follows: 'Here lies Master John Smyth, formerly vicar of this church. He died the thirtieth day of October, A.D. 1433. Amen.' Sometimes hearts are represented as bleeding, or sprinkled with drops of blood, which was probably to symbolize extreme penitence, or special devotedness to a religious life.  An example occurs on a brassin the church of Lillingstone Dayrell, Bucks, and is represented in the accompanying wood-cut. The heart is inscribed with the letters J. H. C., and is held in two hands cut off at the wrists, which are clothed in richly-worked ruffles. This heart commemorates the interment of John Merston, rector, who died in 1416. A heart is sometimes placed on the breast, or held in the hands of an effigy representing the person commemorated. The latter case is probably in allusion to Lamentations iii. 41. In such instances, sepulchral hearts are to be regarded as merely emblematic, or, being the chief organ of life, as representatives of the whole body. But in many instances they mark the burial of hearts alone. Thus, in Chichester Cathedral is a slab of Purbeck marble, on which is chiseled a trefoil enclosing hands holding a heart, and surrounded by this inscription: ICI GIST LE COUER MAUDE DE The rest of the inscription has been obliterated. Another interesting memorial of the burial of a heart formerly existed in Gaxley Church, Huntingdonshire. This consisted of a small trefoil-headed recess, sculptured in stone, and containing a pair of hands holding a heart. Behind this recess was found a round box, about four inches in diameter, which probably had contained a heart that had perished, as it was empty when discovered. The burial of hearts appears to have been often attended with some funereal ceremony. The most remarkable instance on record occurred so recently as the 16th of August 1775. This was the burial, as it was called, of White-head's heart. Paul Whitehead was the son of a London tradesman, and was himself apprenticed to a woollen-draper, but having received a superior education, and imbibed a literary bias, he relinquished business as soon as the terms of his apprenticeship were completed. He entered into various literary projects, and published several pieces, both in prose and verse, chiefly of a satirical character. In his poetical satires, he adopted Pope as his model, but, to use his own expression, 'he found that their powers were differently appreciated.' His effusions, however, were not unsuccessful, especially those of a political character, which he supported by the active and zealous part lie took at a contested election for Westminster. His talent and services were so far appreciated by his party, that Sir Francis Dashwood, afterwards Lord le Despencer, procured for him an appointment worth about £800 per annum. This, together with his wife's fortune of £10,000, placed him in affluent circumstances, and he passed the remainder of his life in comparative retirement at Twickenham. His compositions were of temporary interest, and he appears to have rightly estimated them himself, for he positively refused to collect them for a standard edition. His moral character, in early life, may be conceived from his being not only a member, but the secretary of the notorious Medmenham Club, or the mock Monks of St. Francis. In later life, his habits were respectable, and he possessed a benevolent and hospitable disposition. He died on the 30th of December 1774, aged sixty-four, and among many other legacies, he bequeathed 'his HEART to his noble friend and patron, Lord le Despencer, to be deposited in his mausoleum at West Wycombe, a village two miles from the town of High Wycombe and adjoining Wycombe Park, his lordship's place of residence.' This mausoleum, which was built with funds bequeathed by George Bubb Dodington, Lord Melcombe Regis, is a large hexagonal roofless building, with recesses in the walls for the reception of busts, urns, or other sepulchral monuments. It stands within the churchyard near the east end of the church, which is also a very singular edifice, built by Lord le Despencer on a remarkably lofty hill, and about half a mile from the village. Whitehead's heart, by order of Lord le Despencer, was wrapped in lead, and enshrined in a marble urn, which cost £50, and on the 16th of August 1775, eight months after Whitehead's death, was conveyed from London to be solemnly deposited within the mausoleum. At twelve o'clock, the precious relic, having arrived within a short distance of Wycombe, was carried forward, accompanied by the following procession: Dr. Arnold, Mr. Atterbury, and another walked on the side of the procession all the way, with scrolls of paper in their hands, beating time. The 'Dead March' in Saul was played the whole way by the flutes, horns, and bassoons, successively with the fifes and drums. The church-bell continued tolling, and great guns were discharged every three minutes and a half. The hill on which the church stands was crowded with spectators, while the procession, moving very slowly up, was an hour in reaching the mausoleum, and another hour was spent in marching round it, and performing funereal glees. The urn was then borne with much ceremony into the mausoleum, and placed on a pedestal in one of the niches, with this inscription underneath: PAUL WHITEHEAD OF TWICKENHAM, ESQR. Ob. 1775 Unhallowed hands, this urn forbear, No gems, nor orient spoilLie here concealed; but what 's more rare, A heart that knew no guile. The ceremony was concluded by the soldiers firing three volleys, and then marching off with the drums and fifes playing a merry tune. On the next day, a new oratorio, called Goliah, composed by Mr. Atterbury, was performed in the church. The heart used to be often taken out of the urn, to be shewn to visitors, and in 1829, notwithstanding the warning epitaph, was stolen, and has never been recovered. |