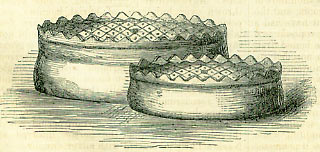

6th MarchBorn: Michael Angelo Buonarotti, painter, sculptor, and architect, 1474, Chiusi; Francesco Guicciardini, diplomatist, 1482, Florence; Bishop Francis Atterbury, 1662, Milton; Vice-Admiral Sir Charles Napier, 1786, Merchistoun. Died: Roger Lord Grey de Ruthyn, 1352: Sir John Hawkwood, first English general, 1393, Florence; Zachary Ursinus, German divine, 1583, Neustadt; Philip, third Earl of Leicester, 1693: Lord Chief Justice Sir John Holt, 1710, Redgrave; Philip, first Earl of Hardwicke, Lord Chancellor, 1764, Wimpole; G. T. F. Raynal, philosophical historian, 1796, Passey; the Rev. Dr. Samuel Parr, 1825, Hatton: George Mickle Kemp, architect (Scott Monument), Edinburgh: Professor Heeren, history and antiquities; Benjamin Travers, surgeon, 1858. Feast Day: St. Fridolin, abbot, 538. St Baldred, of Scotland, about 608. Saints Kyneburge, Kyneswide, and Tibba, 7th century. St. Chrodegang, bishop of Metz, 766. St. Cadroe, about 975. Colette, virgin and abbess, 1447. BISHOP ATTERBURYIn Atterbury we find one of the numerous shipwrecks of history. Learned, able, eloquent, the Bishop of Rochester lost all through hasty, incorrect thinking, and an impetuous and arrogant temper. He had convinced himself that the exiled Stuart princes might be restored to the throne by the simple process of bringing up the next heir as a Protestant, failing to see that the contingency on which he rested was unattainable. One, after all, admires the courage which prompted the fiery prelate, at the death of Queen Anne, to offer to go out in his lawn sleeves and proclaim the son of James II, which would have been a directly treasonable act: we must also admit that, though he doubtless was guilty of treason in favour of the Stuarts, the bill by which he lost his position and was condemned to exile, proceeded on imperfect evidence, and was a dangerous kind of measure. To consider Atterbury as afterwards attached to the service of the so-called Pretender,-wasting bright faculties on the petty intrigues of a mock court, and gradually undergoing the stern correction of Fact and Truth for the illusory political visions to which he had sacrificed so much,-is a reflection not without its pathos, or its lesson. Atterbury ultimately felt the full weight of the desolation which he had brought upon himself. He died at Paris, on the 15th of February 1732. A specimen of the dexterous wit of Atterbury in debate is related in connection with the history of the Occasional Conformity and Schism Bills, December 1718. On that occasion, Lord Coningsby rebuked the Bishop for having, the day before, assumed the character of a prophet. 'In Scripture,' said this simple peer, 'I find a prophet very like him, namely Balaam, who, like the right reverend lord, drove so very furiously, that the ass he rode upon was constrained to open his mouth and reprove him.' The luckless lord having sat down, the bishop rose with a demure and humble look, and having him, went on to say that 'the application of Balaam to him, though severe, was certainly very happy, the terms prophet and priest being often promiscuously used. There wanted, however, the application of the ass: and it seemed as if his lordship, being the only person who had reproved him, must needs take that character upon himself.' From that day, Lord Coningsby was commonly recognised by the appellation of 'Atterbury's Pad.' G. M. KEMPThe beauty of the monument to Sir Walter Scott at Edinburgh becomes the more impressive when we reflect that its designer was a man but recently emerged at the time from the position of a working carpenter. It is a Gothic structure, about 185 feet high, with exquisite details, mostly taken from Melrose Abbey. Kemp's was one of a number of competing plans, given in with the names of the designers in sealed envelopes: so that nothing could be more genuine than the testimony thus paid to his extraordinary genius. In his earlier days as a working carpenter, Kemp adopted the plan of travelling from one great continental dom-kirk or cathedral to another, supporting himself by his handicraft while studying the architecture of the building. It was wonderful how much knowledge he thus acquired, as it were at his own hand, in the course of a few years. He never obtained any more regular education for his eventual profession. Kemp was a man of modest, almost timid demeanour, very unlike one designed to push his way in the world. After becoming a person of note, as entrusted with the construction of Scotland's monument to the most gifted of her sons, he used to relate, as a curious circumstance, the only connexion he had ever had with Scott in life. Travelling toilsomely one hot day between Peebles and Selkirk, with his tools over his back, he was overtaken by a carriage containing a grey-haired gentleman, whom he did not know. The gentleman, observing him, stopped the carriage, and desired the coachman to invite the wayfaring lad to a seat on the box. He thus became the subject of a characteristic piece of benevolence to the illustrious man with whose name he was afterwards to meet on so different a level. Most sad to relate, while the monument was in the progress of construction, the life of the architect was cut short by accident, he having fallen into a canal one dark evening, in the course of his homeward walk. MIDLENT, OR MOTHERING SUNDAYIn the year 1864 the 6th of March is the fourth Sunday in Lent, commonly called Midlent Sunday. Another popular name for the day is Mothering Sunday, from an ancient observance connected with it. The harshness and general painfulness of life in old times must have been much relieved by certain simple and affectionate customs which modern people have learned to dispense with. Amongst these was a practice of going to see parents, and especially the female one, on the present, such as a cake or a trinket. A youth engaged in this amiable act of duty was said to go a-mothering, and thence the day itself came to be called Mothering Sunday. One can readily imagine how, after a stripling or maiden had gone to service, or launched in independent housekeeping, the old bonds of filial love would be brightened by this pleasant annual visit, signalised, as custom demanded it should be, by the excitement attending some novel and perhaps surprising gift. There was also a cheering and peculiar festivity appropriate to the day, the prominent dish being furmety-which we have to interpret as wheat grains boiled in sweet milk, sugared and spiced. In the northern parts of England, and in Scotland, there seems to have been a greater leaning to steeped pease fried in butter, with pepper and salt. Pancakes so composed passed by the name of carlings: and so conspicuous was this article, that from it Carling Sunday became a local name for the day. Tid, Mid, and Misera, Carling, Palm, Pase-egg day, remains in the north of England as an enumeration of the Sundays of Lent, the first three terms probably taken from words in obsolete services for the respective days, and the fourth being the name of Midlent Sunday from the cakes by which it was distinguished. Herrick, in a canzonet addressed to Dianeme, says I'll to thee a simnel bring, 'Gainst thou go a-mothering: So that, when she blesses thee, Half that blessing thou'lt give me. He here obviously alludes to the sweet cake which the young person brought to the female parent as a gift: but it would appear that the term 'simnel' was in reality applicable to cakes which were in use all through the time of Lent. We are favoured by an antiquarian friend with the following general account of Simnel Cakes.  It is an old custom in Shropshire and Herefordshire, and especially at Shrewsbury, to make during Lent and Easter, and also at Christmas, a sort of rich and expensive cakes, which are called Simnel Cakes. They are raised cakes, the crust of which is made of fine flour and water, with sufficient saffron to give it a deep yellow colour, and the interior is filled with the materials of a very rich plum-cake, with plenty of candied lemon peel, and other good things. They are made up very stiff; tied up in a cloth, and boiled for several hours, after which they are brushed over with egg, and then baked. When ready for sale the crust is as hard as if made of wood, a circumstance which has given rise to various stories of the manner in which they have at times been treated by persons to whom they were sent as presents, and who had never seen one before, one ordering his simnel to be boiled to soften it, and a lady taking hers for a footstool. They are made of different sizes, and, as may be supposed from the ingredients, are rather expensive, some large ones selling for as much as half-a-guinea, or even, we believe, a guinea, while smaller ones may be had for half-a-crown. Their form, which as well as the ornamentation is nearly uniform, will be best understood by the accompanying engraving, representing largo and small cakes as now on sale in Shrewsbury. The usage of these cakes is evidently one of great antiquity. It appears from one of the epigrams of the poet Herrick, that at the beginning of the seventeenth century it was the custom at Gloucester for young people to carry simnels as presents to their mothers on Midlent Sunday (or Mothering Sunday). It appears also from some other writers of this age, that these simnels, like the modern ones, were boiled as well as baked. The name is found in early English and also in very old French, and it appears in mediæval Latin under the form simanellus or siminellus. It is considered to be derived from the Latin simile, fine flour, and is usually interpreted as meaning the finest quality of white bread made in the middle ages. It is evidently used, however, by the mediæval writers in the sense of a cake, which they called in Latin of that time artocopus, which is constantly explained by simnel in the Latin-English vocabularies. In three of these, printed in Mr. Wright's Volume of Vocabularies, all belonging to the fifteenth century, we have 'Hic artocopus, anglice symnelle,' 'Hic artocopus, a symnylle,' and 'artocopus, anglice a symnella;' and in the latter place it is further explained by a contemporary pen-and-ink drawing in the margin, representing the simnel as seen from above and sideways, of which we give below a fac-simile. It is quite evident that it is a rude representation of a cake exactly like those still made in Shropshire. The ornamental border, which is clearly identical with that of the modern cake, is, perhaps, what the authorities quoted by Ducange v. simila, mean when they spoke of the cake as being foliata. In the Dictionaries of John de Garlande, compiled at Paris in the thirteenth century, the word simineus or simnenels, is used as the equivalent to the Latin placentæ, which are described as cakes exposed in the windows of the hucksters to sell to the scholars of the University and others. We learn from Ducange that it was usual in early times to mark the simnels with a figure of Christ or of the Virgin Mary, which would seem to shew that they had a religious signification. We know that the Anglo-Saxon, and indeed the German race in general, were in the habit of eating consecrated cakes at their religious festivals. Our hot cross buns at Easter are only the cakes which the pagan Saxons ate in honour of their goddess Eastre, and from which the Christian clergy, who were unable to prevent people from eating, sought to expel the paganism by marking them with the cross. It is curious that the use of these cakes should have been preserved so long in this locality, and still more curious are the tales which have arisen to explain the meaning of the name, which had been long forgotten. Some pretend that the father of Lambert Simnel, the well-known pretender in the reign of Henry VII, was a baker, and the first maker of simnels, and that in consequence of the celebrity he gained by the acts of his son, his cakes have retained his name. There is another story current in Shropshire, which is much more picturesque, and which we tell as nearly as possible in the words in which it was related to us. Long ago there lived an honest old couple, boasting the names of Simon and Nelly, but their surnames are not known. It was their custom at Easter to gather their children about them, and thus meet together once a year under the old homestead. The fasting season of Lent was just ending, but they had still left some of the unleavened dough which had been from time to time converted into bread during the forty days. Nelly was a careful woman, and it grieved her to waste anything, so she suggested that they should use the remains of the Lenten dough for the basis of a cake to regale the assembled family. Simon readily agreed to the proposal, and further reminded his partner that there were still some remains of their Christmas plum pudding hoarded up in the cupboard, and that this might form the interior, and be an agreeable surprise to the young people when they had made their way through the less tasty crust. So far, all things went on harmoniously; but when the cake was made, a subject of violent discord arose, Sim insisting that it should be boiled, while Nell no less obstinately contended that it should be baked. The dispute ran from words to blows, for Nell, not choosing to let her province in the household be thus interfered with, jumped up, and threw the stool she was sitting on at Sim, who on his part seized a besom, and applied it with right good will to the head and shoulders of his spouse. She now seized the broom, and the battle became so warm, that it might have had a very serious result, had not Nell proposed as a compromise that the cake should be boiled first, and afterwards baked. This Sim acceded to, for he had no wish for further acquaintance with the heavy end of the broom. Accordingly, the big pot was set on the fire, and the stool broken up and thrown on to boil it, whilst the besom and broom furnished fuel for the oven. Some eggs, which had been broken in the scuffle, were used to coat the outside of the pudding when boiled, which gave it the shining gloss it possesses as a cake. This new and remarkable production in the art of confectionery became known by the name of the cake of Simon and Nelly, but soon only the first half of each name was alone pre-served and joined together, and it has ever since been known as the cake of Sim-Nel, or Simnel! TRADITION AND TRUTHThe value of popular tradition as evidence in antiquarian inquiries cannot be disputed, though in every instance it should be received with the greatest caution. A few instances of traditions, existing from a very remote period and verified in our own days, are worthy of notice. On the northern coast of the Firth of Forth, near to the town of Largo, in Fifeshire, there has existed from time immemorial an eminence known by the name of Norie's Law. And the popular tradition respecting this spot, has ever been that a great warrior, the leader of a mighty army, was buried there, clad in the silver armour he wore during his lifetime. Norie's Law is evidently artificial, and there can be no wonder that the neighbouring country people should suppose that a great chief had been buried underneath it, for the interment of warrior chieftains under artificial mounds, near the sea, is as ancient as Homer. Hector, speaking of one whom he intended to slay in single combat, says: The long-haired Greeks To him, upon the shores of Hellespont, A mound shall heap; that those in after times, Who sail along the darksome sea, shall say, This is the monument of one long since Borne to his grave, by mighty Hector slain. Our Anglo-Saxon ancestors buried their warrior leaders in the same manner. The foregoing quotation seems almost parodied in the dying words of the Saxon Beowulf: Command the famous in war To make a mound, Bright after the funeral fire, Upon the nose of the promontory; Which shall, for a memorial To my people, rise high aloft, On Heonesness; That the sea-sailors May afterwards call it Beowulf's Barrow, When the Brentings, Over the darkness of the flood, Shall sail afar. So it was only natural for the rustic population to say that a chief was buried under Norie's Law. Agricultural progress has, in late years, thrown over hundreds of burial barrows, ex-posing mortuary remains, and there are few labourers in England or Scotland who would not say, on being pointed out a barrow, that a great man, at some distant period, had been interred beneath it. But silver armour, with one single exception, has never been found in barrows; and as Norie's Law is actually the barrow in which silver accoutrements were found, the tradition of the people was fully verified. For only by tradition, and that from a very distant period, could they have known that the person interred at Norie's Law was buried with silver armour. It appears that, about the year 1819, a man in humble life and very moderate circumstances, residing near Largo, was-greatly to the surprise of his neighbours-observed to have suddenly become passing rich for one of his position and opportunities. A silversmith, in the adjacent town of Cupar, had about the same time been offered a considerable quantity of curious antique silver for sale; part of which he purchased, but a larger part was taken to Edinburgh, and disposed of there. Contemporary with these events, a modern excavation was discovered in Norie's Law, so it did not require a witch to surmise that a case of treasure-trove had recently occurred. The late General Durham, then owner of the estate, was thus led to make inquiries, and soon discovered that the individual alluded to, induced by the ancient tradition, had made an excavation in the Law, and found a considerable quantity of silver, which he had disposed of as previously noticed. But influenced, as some say, by a feeling of a conscientious, others of a superstitious character, he did not take all the silver he discovered, but left a large quantity in the Law. Besides, as this ingenious individual conducted his explorations at night, it was supposed that he might have overlooked part of the original deposit. Acting in accordance with this intelligence, General Durham caused the Law to be carefully explored, and found in it several lozenge-shaped plates of silver, that undoubtedly had been the scales of a coat of mail, besides a silver shield and sword ornaments, and the mounting of a helmet in the same metal. Many of these are still preserved at Largo House, affording indisputable evidence of the very long perseverance and consistency which may characterise popular tradition. Our next illustration is from Ireland, and it happened about the commencement of the last century. At Ballyshannon, says Bishop Gibson, in his edition of Camden's Britannia, were two pieces of gold discovered by a method very remarkable. The Bishop of Derry being at dinner, there came in an old Irish harper, and sang an ancient song to his harp. His lordship, not understanding Irish, was at a loss to know the meaning of the song; but upon inquiry, he found the substance of it to be this, that in such a place, naming the very spot, a man of gigantic stature lay buried; and that over his breast and back were plates of pure gold, and on his fingers rings of gold so large that an ordinary man might creep through them. The place was so exactly described, that two persons there present were tempted to go in quest of the golden prize which the harper's song had pointed out to them. After they had dug for some time, they found two thin pieces of gold, circular, and more than two inches in diameter. This discovery encouraged them to seek next morning for the remainder, but they could find nothing more. In all probability they were not the first inquisitive persons whom the harper's song had sent to the same spot. Since the ancient poetry of Ireland has become an object of learned research, the very song of the harper has been identified and printed, though it was simply traditional when sung before the Bishop. It is called Moira Borb; and the verse, which more particularly suggested the remarkable discovery, has been translated thus: In earth, beside the loud cascade, The son of Sora's king we laid; And on each finger placed a ring Of gold, by mandate of our King. The 'loud cascade' was the well-known water-fall at Ballyshannon, now known as 'the Salmon-leap.' Another instance of a similar description occurred in Wales. Near Mold, in Flintshire, there had existed from time immemorial a burial mound or barrow, named by the Welsh peasantry Bryn-yr-ellylon, the Hill of the Fairies. In 1827, a woman returning late from market, one night, was extremely frightened by seeing, as she solemnly averred, a spectral skeleton standing on this mound and clothed in a vestment of gold, which shone like the noon-day sun. Six years after-wards, the barrow, being cleared away for agricultural purposes, was found to contain urns and burnt bones, the usual contents of such places. But besides these, there was a most unusual object found, namely, a complete skeleton, round the breast of which was a corslet of pure gold, embossed with ornaments representing nail heads and lines. This unique relic of antiquity is now in the British Museum; and, if we are to confine ourselves to a natural explanation, it seems but reasonable to surmise that the vision was the consequence of a lingering remembrance of a tradition, which the woman had heard in early life, of golden ornaments buried in the goblin hill. CANTERBURY PILGRIM-SIGNSThe Thames, like the Tiber, has been the conservator of many minor objects of antiquity, very useful in aiding us to obtain a more correct knowledge of the habits and manners of those who in former times dwelt upon its banks. Whenever digging or dredging disturbs the bed of the river, some antique is sure to be exhumed. The largest amount of discovery took place when old London-bridge was removed, but other causes have led to the finding of much that is curious. Among these varied objects not the least interesting are a variety of small figures cast in lead, which. prove to be the 'signs' worn by the pilgrims returned from visiting the shrine of St. Thomas Becket at Canterbury, and who wore them in their hats, or as brooches upon some portion of their dress, in token of their successful journey. The custom of wearing these brooches is noted by Giraldus Cambrensis as early as the twelfth century. That ecclesiastic returned from a continental journey by way of Canterbury, and stayed some days to visit Becket's shrine; on his arrival in London he had an interview with the Bishop of Winchester, and he tells us that the Bishop, seeing him and his companions with signs of St. Thomas hanging about their necks, remarked that he perceived they had just come from Canterbury. Erasmus, in his colloquy on pilgrimages, notes that pilgrims are 'covered on every side with images of tin and lead.' The cruel and superstitions Louis XI. of France, customarily wore such signs stuck around his hat. The anonymous author of the Supplement to Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, described that famed party of pilgrims upon their arrival at the archiepiscopal city, and says: Then, as manner and custom is, signs there they bought, For men or contre' should know whom they had sought. Each man set his silver in such thing as he liked, And in the meanwhile, the matter had y-piked His bosom full of Canterbery brooches. The rest of the party, we are afterwards told, 'Set their signs upon their heads, and some upon their cap.' They were a considerable source of revenue to the clergy who officiated at celebrated shrines, and have been found abroad in great numbers, bearing the figures of saints to whom it was customary to do honour by pilgrimages in the middle ages. The shells worn by the older pilgrims to Compostella, may have originated the practice; which still survives in Catholic countries, under the form of the medalets, sold on saints' days, which have touched sacred relics, or been consecrated by ecclesiastics.  The first specimen of these Canterbury brooches we engrave, and which appears to be a work of the fourteenth century, has a full length of St. Thomas in pontificals in the act of giving the pastoral benediction. The pin which was used to attach it to the person, will be perceived behind the figure; it seems best fitted to be secured to, and stand upright upon, the hat or cap of the pilgrim.  Our second specimen takes the ordinary form of a brooch, and has in the centre the head only of Becket; upon the rim are inscribed the words Caput Thome. The skull of the saint was made a separate exhibition in the reign of Edward III, and so continued until the days of Henry VIII. The monks of Canterbury thus made the most of their saint, by exhibiting his shrine at one part of the cathedral, his skull at another, and the point of the sword of Richard Brito, which fractured it, in a third place. The wealth of the church naturally became great, and no richer prize fell into the rapacious hands of the Royal suppressor of monasteries than Canterbury.  These signs were worn, not only as indications of pilgrimage performed, but as charms or protections against accidents in the journey; and it would appear that the horses of the pilgrims were supplied with small bells inscribed with the words Campana Thorne, and of which also we give a specimen. All these curious little articles have been found at various times in the Thames, and are valuable illustrative records, not only of the most popular of the English pilgrimages, bat of the immortal poem of Geoffrey Chaucer, who has done so much toward giving it an undying celebrity. |