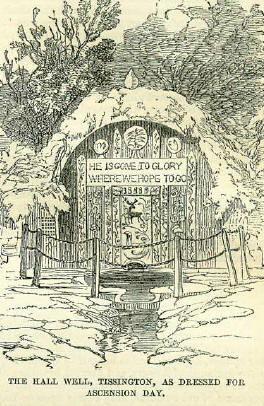

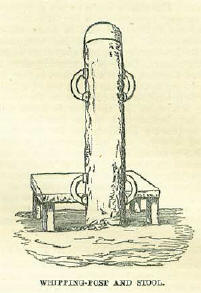

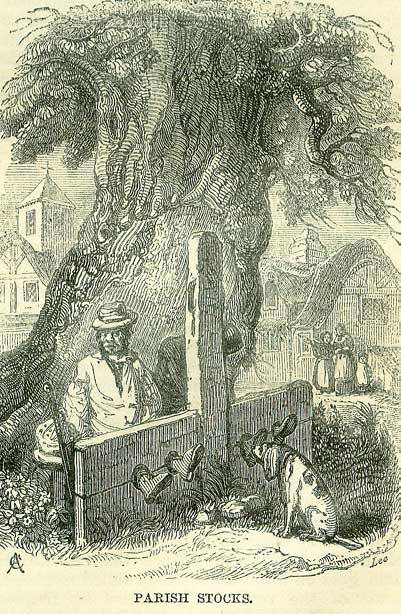

5th MayBorn: Emperor Justinian, 482, Tauresiurn, in Bulgaria. Died: Paulus Æmilius, 1529, Paris; Samuel Cooper, 1672; Stephen Morin, 1700, Amsterdam; John Pichon, 1751; Thomas Davies (dramatic biography), 1785, London; Pierre J. G. Cabanis, French materialist philosopher, 1808; Robert Mylne, architect, 1811; Napoleon Bonaparte, ex-Emperor of the French, 1821, St. Helena; Rev. Dr. Lent Carpenter, theologian, 1840; Sir Robert Harry Inglis, Bart., political character, 1855; Charles Robert Leslie, American artist, 1859, London. Feast Day: St. Hilary, Archbishop of Arles, 449. St. Mauront, abbot, 706. St. Avertin, confessor, about 1189. St. Angelus, Carmelite friar, martyr, 1225. St. Pius V, pope, 1572. ASCENSION DAY (1864)Ascension Day, or Holy Thursday, is a festival observed by the Church of England in commemoration of the glorious ascension of the Messiah into heaven, 'triumphing over the devil, and leading captivity captive;' opening the kingdom of heaven to all believers.' It occurs forty days after Easter Sunday, such being the number of days which. the Saviour passed on earth after his resurrection. The observance is thought to be one of the very earliest in the church-so early, it has been said, as the year 68. WELL-DRESSING AT TISSINGTON Still, Dovedale, yield thy flowers to deck the fountains Of Tissington upon its holyday; The customs long preserved among the mountains Should not be lightly left to pass away. They have their moral; and we often may Learn from them how our wise forefathers wrought, When they upon the public mind would lay Some weighty principle, some maxim brought Home to their hearts, the healthful product of deep thought. Such was our feeling when our kind landlady at Matlock reminded us that on the following day, being Holy Thursday, or Ascension Day, there would take place the very ancient and well kept-up custom of dressing the wells of Tissington with flowers. She recommended us on no account to miss the opportunity, 'for the festivity draws together the rich and poor for many miles round,' said she; 'and the village looks so pretty you cannot but admire it.' It was one of those lovely May mornings when we started on our twelve miles drive which give you the anticipation of enjoyment; the bright sun was shining on the hills surrounding the romantically situated village of Matlock, the trees were already decked with the delicate spring tints of pale browns, olives, and greens, which form even a more pleasing variety to the artist' s eye than the gorgeous colours of the dying autumn; whilst the air had the crispness of a sharp frost, which had hardened the ground during the night, making our horses step merrily along.  We were soon at Willersley, with its woods and walks overhanging the Derwent, and connected in its historical associations with two remarkable but very different characters, having been formerly a possession of the Earl of Shrewsbury, the husband of that 'sharpe and bitter shrewe,' as the Bishop of Lichfield calls her, who figured so prominently in the reigns of Mary and Elizabeth. Married no less than four times, she was the ancestress of some of the most noble families in England. At the early age of fourteen she became the wife of Robert Barley, Esq., the union not lasting much more than a year. Sir William Cavendish then aspired to her hand, by which the fine old seat and lands of Hardwicke Hall, of which she was the heiress, came into the Devonshire family. Sir William was a man of eminent talent, and the zeal he displayed in the cause of the Reformation recommended him highly to his sovereign. He was better fitted to cope with his wife' s masculine understanding and violent temper than her last husband, the Earl of Shrewsbury, who gives vent to some very undignified remonstrances in a letter to the Earl of Leicester, dated 1585. The queen had, it seems, taken the part of her own sex, and ordered the earl an allowance of five hundred a-year, leaving all the lands in the power of his wife: 'Sith that her majestie hathe sett dowen this hard sentence againste me, to my perpetual infamy and dishonour, to be ruled and oberauue by my wief, so bad and wicked a woman; yet her majestie shall see that I obey her commandemente, thoughe no curse or plage in the erthe cold be more grievous to me. It is to much to make me my wiefe' s pencyoner, and sett me downe the demeanes of Chatsworth, without the house and other landes leased.' From this time the pair lived separate; whilst the restless mind of the countess still pursued the political intrigues which had been the terror of her husband, and the aggrandizement of her family. She bought and sold estates, lent money, farmed, and dealt in lead, coals, and timber, patronized the wits of the day, who in return flattered but never deceived her, and died at the advanced age of eighty-seven, immensely rich, leaving the character behind her of being 'a proud, furious, selfish, and unfeeling woman.' She and the earl were for some time the custodians of the unfortunate Mary Queen of Scots, who passed a part of her imprisonment at Chatsworth, and at the old Hall at Hardwicke, which is now in ruins. Very different from this has been the career of the present proprietor of beautiful Willersley, whose ancestor, Richard Arkwright, springing from a very humble origin, created his own fortune, and provided employment for thousands of his fellow-creatures by his improvements in cotton spinning. A history so well known needs no farther comment here, and we drive on through the Via Gellia, with its picturesque rocks and springing vegetation, gay with The primrose drop, the spring's own spouse, Bright daisies, and the lips-of-cows, The garden star, the queen of May, The rose, to crown the holyday. We cannot wonder that the Romans dedicated this lovely season to Flora, whom they depicted as strewing the earth with flowers, attended by her spouse, Zephyr; and in honour of whom they wove garlands of flowers, and carried branches of the newly-budded trees. From the entire disappearance of old customs, May comes upon us unwelcomed and unnoticed. In the writer's child-hood a May-pole carried about in the hand was common even in towns; but now no children understand the pleasures of collecting the way-side and garden flowers, and weaving them into the magic circle. Still less applicable are L. E. L.'s beautiful lines: Here the Maypole rears its crest, With the rose and hawthorn drest; In the midst, like the young queen Flower-crowned, of the rural green, Is a bright-checked girl, her eye Blue, like April's morning sky. Farewell, cities ! who could bear All their smoke and all their care, All their pomp, when wooed away By the azure hours of May? Give me woodbine-scented bowers, Blue wreaths of the violet flowers, Clear sky, fresh air, sweet birds, and trees, Sights and sounds, and scenes like these. We could not but notice, in passing through the meadows near Brassington, those singular limestone formations which crop out of the ground in the most fantastic forms, resembling arrows and spires, and which the people designate by various names, such as Peter's Pike, Reynard's Tor. Then came the village of Bradbourne, and the pretty foot-bridge, close by the mill, crossing Bentley Brook, a little stream mentioned by Walton as 'full of good trout and grayling.' This bridge is the direct foot-road to Tissington, at which 'village of the holy wells ' we soon arrived, and found it decked out in all its bravery. It has in itself many points of attraction independent of the ornaments of the day ; the little stream that runs through the centre, the rural-looking cottages and comfortable farmhouses, the old church, which retains the traces of Saxon architecture, and, lastly, the Hall, a fine old edifice, belonging to the ancient family of the Fitzherberts, who reside there, the back of which comes to the village, the front looking into an extensive, well-wooded park. When we drove into the village, though it was only ten o'clock, we found it already full of people from many miles round, who had assembled to celebrate the feast : for such indeed it was, all the characteristics of a village wake being there in the shape of booths, nuts, gingerbread, and toys to delight the young. We went immediately to the church, foreseeing the difficulty there would be in getting a seat, nor were we mistaken; for, though we were accommodated, numbers were obliged to remain outside, and wait for the service peculiar to the wells. The interior of the church is ornamented with many monuments of the Fitzherbert family, and the service was performed in rural style by a band of violinists, who did their best to make melody. As soon as the sermon was ended, the clergyman left the pulpit, and marched at the head of the procession which was formed into the village; after him came the band; then the family from the hall, and their visitors, the rest of the congregation following; and a, halt was made at the first of the wells, which are five in number, and which we will now attempt to describe. The name of 'well' scarcely gives a proper idea of these beautiful structures: they are rather fountains, or cascades, the water descending from above, and not rising, as in a well. Their height varies from ten to twelve feet; and the original stone frontage is on this day hidden by a wooden erection in the form of an arch, or some other elegant design: over these planks a layer of plaster of Paris is spread, and whilst it is wet, flowers without leaves are stuck in it, forming a most beautiful mosaic pattern. On one, the large yellow field ranunculus was arranged in letters, and so averse of scripture or of a hymn was recalled to the spectator's mind; on another, a white dove was sculptured in the plaster, and set in a groundwork of the humble violet; the daisy, which our poet Chaucer would gaze upon for hours together, formed a diaper work of red and white; the pale yellow primrose was set off by the rich red of the ribes; nor were the coral berries of the holly, mountain ash, and yew forgotten; these are carefully gathered and stored in the winter, to be ready for the May-day fete. It is scarcely possible to describe the vivid colouring and beautiful effect of these favourites of nature, arranged in wreaths, and garlands, and devices of every hue; and then the pure, sparkling water, which pours down from the midst of them unto the rustic moss-grown stones beneath, completes the enchantment, and makes this feast of the well-flowering one of the most beautiful of all the old customs that are left in 'merrie England.' The groups of visitors and country people, dressed in their holiday clothes, stood reverently round, whilst the clergyman read the first of the three psalms appointed for the day, and then gave out one of Bishop Heber's beautiful hymns, in which all joined with heart and voice. When this was over, all moved forwards to the next well, where the next psalm was read and another hymn sung; the epistle and gospel being read at the last two wells. The service was now over, and the people dispersed to wander through the village or park, which is thrown open; the cottagers vie with each other in showing hospitality to the strangers, and many kettles are boiled at their fires for those who have brought the materials for a picnic on the green. It is welcomed as a season of mirth and good fellowship, many old friends meeting then to separate for another year, should they be spared to see the well-dressing again; whilst the young people enjoy their games and country pastimes with their usual vivacity. The origin of this custom of dressing the wells is by some persons supposed to be owing to a fearful drought which visited Derbyshire in 1615, and which is thus recorded in the parish registers of Youlgrave: There was no rayne fell upon the earth from the 25th day of March till the 2nd day of May, and then there was but one shower; two more fell betweene then and the 4th day of August, so that the greatest part of this land were burnt upp, bothe corn and hay. An ordinary load of hay was at £2, and little or none to be gotte for money. The wells of Tissington were flowing during all this time, and the people for ten miles round drove their cattle to drink at them; and a thanksgiving service was appointed yearly for Ascension Day. But we must refer the origin much further back, to the ages of superstition, when the pastimes of the people were all out-of-doors, and when the wakes and daytime dances were on the village green instead of in the close ball-room; it is certainly a 'popish relic,' -perhaps a relic of pagan Rome. Fountains and wells were ever the objects of their adoration. 'Where a spring rises or a river flows,' says Seneca, 'there should we build altars and offer sacrifices;' they held yearly festivals in their honour, and peopled them with the elegant forms of the nymphs and presiding goddesses. In later times holy wells were held in the highest estimation: Edgar and Canute were obliged to issue edicts prohibiting their worship. Nor is this surprising, their very appearance being symbolic of loveliness and purity. The weary and thirsty traveller gratefully hails the 'diamond of the desert,' whether it be in the arid plains of the East, or in the cooler shades of an English landscape. May was always considered the favourable month for visiting the wells which possessed a charm for curing sick people; but a strict silence was to be preserved both in going and coming back, and the vessel in which the water was carried was not to touch the ground. After the Reformation these customs were strictly forbidden, as superstitious and idolatrous, the cures which were wrought being doubtless owing to the fresh air, and what in these days we should call hydropathic remedies. In consequence of this questionable origin, whether Pagan or Popish, we have heard some good but straitlaced people in Derbyshire condemn the well-dressing greatly, and express their astonishment that so many should give it their countenance, by assembling at Tissington; but, considering that no superstition is now connected with it, and that the meeting gives unusual pleasure to many, we must decline to agree with them, and hope that the taste of the well-dressers may long meet with the reward of an admiring company. ROBERT MYLNEMr. Mylne, the architect of Blackfriars Bridge in London, had aimed at perfecting himself in his profession by travel, by study, and a careful experience. His temper is said to have been rather peculiar, but his integrity and high sense of duty were universally acknowledged. He was born in Edinburgh in 1733, the son of one respectable architect, and nephew of another, who constructed the North Bridge in that city. The father and grandfather of his father were of the same profession; the latter (also named Robert) being the builder of Holyrood Palace in its present form, and of most of the fine, tall, ashlar-fronted houses which still give such a grandeur to the High-street. Considering that the son and grandson of the architect of Blackfriars Bridge have also been devoted to this profession, we may be said to have here a remarkable example of the perseverance of certain artistic faculties in one family; yet the whole case in this respect has not been stated. In the Greyfriars churchyard, in Edinburgh, there is a handsome monument, which the palace builder reared over his uncle, John Mylne, who died in 1667, in the highest reputation as an architect, and who was described in the epitaph as the last of six generations, who had all been 'master-masons' to the kings of Scotland. It cannot be shown that this statement is true, though it may be so; but it can be pretty clearly proved that there were at least three generations of architects before the one we have called the palace builder; exhibiting, even on this restricted ground, an example of persistent special talents in hereditary descent such as is probably unexampled in any age or country. OPENING OF THE STATES-GENERAL OF FRANCE, 1789This event, so momentous in its consequences as to make it an era in the history of the world, took place at Versailles on the 5th of May, 1789. The first sitting was opened in the Salle de Menus. Nothing could be more imposing than the spectacle that presented itself. The deputies were introduced according to the order and etiquette established in 1614. The clergy, in cassocks, large cloaks, and square caps, or in violet robes and lawn sleeves, were placed on the right of the throne; the nobles, covered with cloth of gold and lace, were conducted to the left; whilst the commons, or tiers etat, were ranged in front, at the end of the hall. The galleries were filled with spectators, who marked with applause those of the deputies who were known to have been favourable to the convention. When the deputies and ministers had taken their places, Louis XVI arrived, followed by the queen, the princes, and a brilliant suite, and was greeted with loud applause. His speech from the throne was listened to with. profound attention, and closed with these words: 'All that can be expected from the dearest interest in the public welfare, all that can be required of a sovereign the first friend of his people, you may and ought to hope from my sentiments. That a happy spirit of union may pervade this assembly, and that this may be an ever-memorable epoch for the happiness and prosperity of the kingdom, is the wish of my heart, the most ardent of my desires; it is, in a word, the reward which I expect for the uprightness of my intentions, and my love of my subjects.' He was followed by Barentin, keeper of the seals, and then by Necker; but neither the king nor his ministers understood the importance of the crisis. A thousand pens have told how their anticipations of a happy issue were frustrated. WHIPPING VAGRANTSThree centuries ago, the flagellation of vagrants and similar characters for slight offences was carried to a cruel extent. Owing to the dissolution of the monasteries, where the poor had chiefly found relief, a vast number of infirm and unemployed persons were suddenly thrown on the country without any legitimate means of support. These destitute persons were naturally led to wander from place to place, seeking a subsistence from the casual alms of any benevolent persons they might chance to meet. Their roving and precarious life soon produced its natural fruits, and these again produced severe measures of repression. By an act passed in 22 Henry VIII, vagrants were to be 'carried to some market town or other place, and there tied to the end of a cart naked, and beaten with whips throughout such market town or other place, till the body should be bloody by reason of such whipping.' The punishment was afterwards slightly mitigated; for by a statute passed in the 39th of Elizabeth's reign, vagrants were only to be stripped naked from the middle upwards, and whipped till the body should be bloody.', Still vagrancy not only continued, but increased, so that several benches of magistrates issued special orders for the apprehension and punishment of vagrants found in their respective districts. Thus, in. the quarter sessions at Wycomb, in Bucks, held on the 5th of May, 1698, an order was passed directing all constables and other parish officers to search for vagrants, &c.; 'and all such persons which they shall apprehend in any such search, or shall take begging, wandering, or misconducting themselves, the said constables, headboroughs, or tything-men, being assisted with some of the other parishioners, shall cause to be whipped naked from the middle upwards, and be openly whipped till the bodies shall be bloody.' This order appears to have been carried into immediate execution, not only within the magisterial jurisdiction of Wycomb, but throughout the county of Buckingham; and lists of the persons whipped were kept in the several parishes, either In the church registers, or in some other parish book. In the book kept in the parish of Lavenden, the record is sufficiently explicit. For example, 'Eliz. Roberts, lately the wife of John Roberts, a tallow-chandler in ye Strand, in Hungerford Market, in ye County of Middlesex, of a middle stature, brown-haired, and black-eyed, aged about - years, was whipped and sent to St. Martin's-in-the-Field, in London, where she was born. 'At Burnham, in the same county, there is in the church register a long list of persons who have been whipped, from which the following specimens are taken- 'Benjamin Smat, and his wife and three children, vagrant beggars; he of middle stature, but one eye, was this 28th day of September 1699, with his wife and children, openly whipped at Boveney, in the parish of Burnham, in the county of Buck., according to ye laws. And they are assigned to pass forth-with from parish to parish by ye officers thereof the next directway to the parish of St. [Se]pulchers Loud., where they say they last inhabited three years. And they are Emitted to be at St. [Se] pulch. within ten days next ensuing. Given under our hands and seals. Will. Glover, Vicar of Burn-ham, and John Hunt, Constable of Boveney.' The majority of those in this list were females-as 'Eliz. Collins, a mayd pretty tall of stature;' 'Anne Smith, a vagrant beggar about fifteen years old;' 'Mary Web, a child about thirteen years of age, a wandering beggar;' 'Isabel Harris, a widd. about sixty years of age, and her daughter, Eliz. Harris, with one child.' Thus it appears that this degrading punishment was publicly inflicted on females without regard to their tender or advanced age. It is, however, only fair to mention, as a redeeming point in the parish officers of Burnham, that they sometimes recommended the poor women whom they had whipped to the tender mercies of the authorities of other parishes through which the poor sufferers had to pass. The nature of these recommendations may be seen from copies of those still remaining in the register, one of which, after the common pre-amble, 'To all constables, headboroughs, and tything-men, to whom these presents shall come,' desires them 'to be as charitable as the law in such cases allows, to the bearer and her two children. 'Cruelty in the first instance, and a re-commendation of benevolence to others in the second, looks like an improved reading of Sidney Smith's celebrated formula- 'A. never sees B. in distress but he wishes C. to go and relieve him. The law of whipping vagrants was enforced in other counties much in the same manner as in Buckinghamshire. The following curious items are from the constable's accounts at Great Staughton, Huntingdonshire: 'Men and women were whipped promiscuously at Worcester till the close of the last century, as may be seen by the corporation records. Male and female rogues were whipped at a charge of 4d. each for the whip's-man. In 1680 there is a charge of 4d. 'for whipping a wench.' In 1742, 1s. 'for whipping John Williams, and exposing Joyce Powell.' In 1759, 'for whipping Elizabeth Bradbury, 2s. 6d.' probably including the cost of the hire of the cart, which was usually charged 1s. 6d. separately.' Whipping, however, was not always executed at the 'cart's tail.' It was, indeed, so ordered in the statute of Henry V III; but by that passed in the 39th of Elizabeth it was not required, and about this time (1596), whipping-posts came into use. When the writings of John Taylor, 'the water-poet,' were published (1630), they appear to have been plentiful, for he says In London, and within a mile I ween, There are of jails or prisons full eighteen; And sixty whipping-posts, and stocks and cages. And in Hudibras we read of An old dull sot, who toll'd the clock For many years at Bridewell-dock; Engaged the constable to seize All those that would not break the peace; Let out the stocks, and whipping post, And cage, to those that gave him most.  On May 5th, 1713, the corporation of Doncaster ordered 'a whipping-post to be set up at the stocks at Butcher Cross, for punishing vagrants and sturdy beggars.' The stocks were often so constructed as to serve both for stocks and whipping-post. The posts which supported the stocks being made sufficiently high, were furnished near the top with iron clasps to fasten round the wrists of the offender, and hold him securely during the infliction of the punishment. Sometimes a single post was made to serve both purposes; clasps being provided near the top for the wrists, when used as a whipping-post, and similar clasps below for the ankles when used as stocks, in which case the culprit sat on a bench behind the post, so that his legs when fastened to the post were in a horizontal position. Stocks and whipping-posts of this description still exist in many places, and persons are still living who have been subjected to both kinds of punishment for which they were designed. Latterly, under the influence, we may suppose, of growing humanity, the whipping part of the apparatus was dispensed with, and the stocks left alone. The weary knife-grinder of Canning, we may remember, only talks of being put in the stocks for a vagrant.  The stocks was a simple arrangement for exposing a culprit on a bench, confined by having his ankles laid fast in holes under a movable board. Each parish had one, usually close to the churchyard, but sometimes in more solitary places. There is an amusing story told of Lord Camden, when a barrister, having been fastened up in the stocks on the top of a hill, in order to gratify an idle curiosity on the subject. Being left there by the absent-minded friend who had locked him in, he found it impossible to procure his liberation for the greater part of a day. On his entreating a chance traveller to release him, the man shook his head, and passed on, remarking that of course he was not put there for nothing. Now-a-days, the stocks are in most places removed as an unpopular object; or we see little more than a stump of them left. The whipping of female vagrants was expressly forbidden by a statute of 1791. OATMEAL-ITS FORMER USE IN ENGLANDEdward Richardson, owner of an estate in the township of Bice, Lancashire, directed, in 1784, that for fifty years after his death there should be, on Ascension Day, a distribution of oatmeal amongst the poor in his neighbourhood, three loads to Ince, one to Abram, and another to Hindley. The sarcastic definition of oats by Johnson, in his Dictionary-'A grain which in England is generally given to horses, but in Scotland supports the people,' has been the subject of much remark. It is, however, worthy of notice that, when the great lexicographer launched this sneer at Caledonia, England herself was not a century advanced from a very popular use of oatmeal. Markham, in his English Housewife, 1653, speaks of oatmeal as a viand in regular family use in England. After giving directions how it should be prepared, he says the uses and virtues of the several kinds are beyond all reckoning. There is, first, the small ground meal, used in thickening pottage of meat or of milk, as well as both thick and thin gruel, 'of whose goodness it is needless to speak, in that it is frequent with every experience.' Then there are oat-cakes, thick and thin, 'very pleasant in taste, and much esteemed.' And the same meal may be mixed with blood, and the liver of sheep, calf, or pig; thus making 'that pudding which is called haggas, or haggus, of whose goodness it is in vain to boast, because there is hardly to be found a man that does not affect them.' It is certainly somewhat surprising thus to find that the haggis of Scotland, which is understood now-a-days to be barely compatible with an Englishman remaining at table, was a dish which nearly every man in England affected in the time of the Commonwealth. More than this, Markham goes on to describe a food called wash-brew, made of the very small oatmeal by frequent steeping of it, and then boiling it into a jelly, to be eaten with honey, wine, milk, or ale, according to taste. 'I have,' says he, 'seen them of sickly and dainty stomachs which have eaten great quantities thereof, beyond the proportion of ordinary meats.' The Scotsman can be at no loss to recognise, in this description, the sowens of his native land, a dish formerly prevalent among the peasantry, but now comparatively little known. To illustrate Markham's remark as to the quantity of this mess which could be eaten, the writer may adduce a fact related to him by his grandmother, who was the wife of an extensive store-farmer in Peeblesshire, from 1768 to 1780. A new plough-man had been hired for the farm. On the first evening, coming home just after the sowens had been prepared, but when no person was present in the kitchen, he began with one of the cogs or bowls, went on to another, and in a little time had despatched the very last of the series; after which. he coolly remarked to the maid, at that moment entering the house, 'Lass, I wish you would tomorrow night make my sowens all in one dish, and not in drippocks and drappocks that way!' LESLIE, CHANTREY, AND SANCHO PANZALeslie, the graceful and genial painter, whose death created a void in many a social circle, is chiefly associated in the minds of the public with two charming pictures-'Uncle Toby and the Widow,' and 'Sancho Panza and the Duchess;' pictures which he copied over and over again, with slight alterations-so many were the persons desirous of possessing then. A curious anecdote is told concerning the latter of the two pictures. When Leslie was planning the treatment of his subject, Chantrey, the sculptor, happened to come in. Chantrey had a hearty, jovial countenance, and a disposition to match. While in lively conversation, he put his finger to his nose in a comical sort of way, and Leslie directly cried out, 'That is just the thing for Sancho Panza,' or something to that effect. He begged Chantrey to maintain the attitude while he fixed it upon his canvas; the sculptor was a man of too much sterling sense to be fidgeted at such an idea; he complied, and the Sancho Panza of Leslie's admirable picture is indebted for much of its striking effect to Chantrey's portraiture. There has, perhaps, never been a story more pleasantly told by a modern artist than this-the half-shrewd, half -obtuse expression of the immortal Sancho; the sweet half-smile, tempered by high-bred courtesy, of the duchess; the sour and stern duenna, Dona Rodriguez; and the mirthful whispering of the ladies in waiting all form a scene which Cervantes himself might have admired. Leslie painted the original for the Petworth collection; then a copy for Mr. Rogers; then another for Mr. Vernon; and then a fourth for an American collection. But these were none of them mere copies; Leslie threw original dashes of genius and humour into each of them, retaining only the main characteristics of the original picture. A POETICAL WILLThe will of John Hedges, expressed in the following quaint style, was proved on the 5th of July, 1737: This fifth day of May, Being airy and gay, To hip not inclined, But of vigorous mind, And my body in health, I'll dispose of my wealth; And of all I'm to have On this side of the grave To some one or other, I think to my brother. But because I foresaw That my brothers-in-law, If I did not take care, Would come in for a share, Which I noways intended, Till their manners were mended And of that there's no sign I do therefore enjoin, And strictly command, As witness my hand, That naught I have got Be brought to botch-pot; And I give and devise, Much as in me lies, To the son of my mother, My own dear brother, To have and to hold All my silver and gold, As th' affectionate pledges Of his brother |