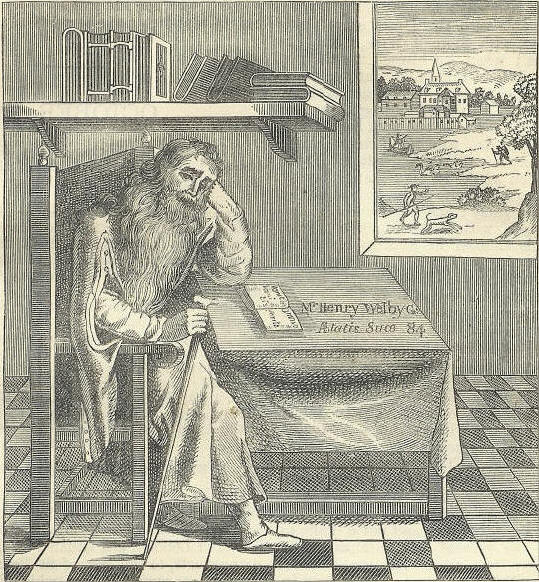

29th OctoberBorn: George Abbot, archbishop of Canterbury, 1562, Guildford; Edmund Halley, astronomer, 1656, Haggerston, near Londoa; James Boswell, biographer of Johnson, 1740, Edinburgh; William Hayley, poet and biographer of Cowper, 1745, Chichester; John Keats, poet, 1796, Pies London. Died: Sir Walter Raleigh, beheaded in Old Palace Yard, 1618; Henry Welby, eccentric character, 1636, London; James Shirley, dramatist, 1666, London; Edmund Calamy, eminent Puritan divine, 1666, London; Admiral Edward Vernon, naval commander, 1757; Jean le Rood d'Alembert, mathematician and encyclopaedist, 1783, Paris; George Morland, animal painter, 1806, London,; Allan Cunningham, poet and miscellaneous writer, 1842, London. Feast Day: St. Narcissus, bishop of Jerusalem, 2nd century. St. Chef or Theuderius, abbot, about 575. JOHN KEATS It is a satisfaction to know that the well-worn story about John Keats being killed by the Quarterly Review a story endorsed by Shelley, and by Byron in Don Juan: Poor fellow! His was an untoward fate; 'Tis strange the mind, that very fiery particle, Should let itself be snuffed out by an article is untrue. Croker's criticism did gall the vanity of which Keats, in common with all poets, possessed an ample share; but he was far too self assured and pugnacious to suffer dangerously from what any body might say of him. Keats was the son of a livery stable keeper, who had risen to comfort by marrying his master's daughter, and was born in Moorfields, London, in 1795. His father, who is described as an active, energetic little man, of much natural talent, was killed by a fall from a horse when John was in his ninth year. His mother, a tall woman with a large oval face and a grave demeanour, after lingering for several years in consumption, died in 1810. A fortune of two thousand pounds was inherited by John. Keats, as a boy in Finsbury, was noted for his pugnacity. It was the time of the great French war, and children caught the martial spirit abroad. In the house, in the stables, in the streets with his brothers, or with any likely combatant, he was ready for a tussle. He was sent to a boarding school at Enfield, kept by the father of Mr. Charles Cowden Clarke, by whom he is remembered for his terrier like character, as well as for his good humour and love of frolic. From school he was taken, at the age of fifteen, and apprenticed for five years to a surgeon and apothecary at Edmonton; an easy distance from Enfield, so that he used to walk over whenever he liked to see the Clarkes and borrow books. He was an insatiable and indiscriminate reader, and spewed no peculiar bias in his tastes, until, in 1812, he obtained in loan Spenser's Fairy Queen. That poem lit the fire of his genius. He could now speak of nothing but Spenser. A world of delight seemed revealed to him. 'He ramped through the scenes of the romance,' writes Mr. Clarke, 'like a young horse turned into a spring meadow;' he got whole passages by heart, which he would repeat to any listener; and would dwell with ecstasy on fine phrases, such as that of 'the sea shouldering whale.' This intense enjoyment soon led to his trying his own hand at verse, and the chief end of his existence became henceforward the reading and writing of poetry. With his friend Cowden Clarke, then a youth like himself, he spent long evenings in enthusiastic discussion of the English poets, shewing a characteristic preference for passages of sweet sensuous description, such as are found in the minor poems of Chaucer, Shakspeare, and Milton, and throughout Spenser, rather than for those dealing with the passions of the human heart. By Clarke the was introduced to Greek poetry, through the medium of translations. They commenced Chapman's Homer one evening, and read till daylight, Keats sometimes shouting aloud with delight as some passage of special energy struck his imagination. Therewith began that remarkable affiliation of his mind to the Greek mythology, which gave to his works so marked a form and colour. From Edmonton he removed to the city for the purpose of 'walking the hospitals,' and became acquainted with Leigh Hunt, Shelley, Hazlitt, Godwin, Hayden, and other literary and artistic people, in whose society his mind expanded and strengthened. At Haydon's one evening, when Wordsworth was present, Keats was induced to recite to him his Hymnn to Pan, which Shelley had praised as 'his surest pledge of ultimate excellence.' Wordsworth listened to the end, and then grimly remarked: 'It is a pretty piece of paganism!' In 1817, Keats published his first book of poems, which attracted no attention. Next year he tried again, and brought out Endymion, a Poetic Romance, for which he was ridiculed as a Cockney poet in the Quarterly and Blackwood's Magazine, and recommended 'to go back to his gallipots,' and reminded that 'a starved apothecary was better than a starved poet.' In 1820 appeared Lamia, the Eve of St. Agnes, and other Poems; these three small volumes, issued within three years, comprised the finished business of his literary life. Keats was of low stature, considerably under middle size. His shoulders were very broad, and his legs so short, that they quite marred the proportion of his figure. 'His head,' says Leigh Hunt, 'was a puzzle for the phrenologists, being remarkably small in the skull a singularity he had in common with Byron and Shelley, whose hats I could not get on.' His face was clearly cut, almost feminine in its general form, and delicately mobile; its worst feature was the mouth, which had a projecting upper lip, giving a somewhat savage and pugilistic impression. His eyes were large and blue, and his hair auburn, and worn parted down the middle. Coleridge, who once shook hands with him, when he met him with Leigh Hunt in a Highgate lane, describes him as 'a loose, slack, not well dressed youth.' At the same time, he turned to Hunt, and whispered: 'There is death in that hand,' although Keats was then apparently in perfect health. The senses of Keats were exquisitely developed. In this fact, in conjunction with a fine imagination and copious language, is discovered the mystery of his poetry, which consists mainly in a relation of luxurious sensations of sight, hearing, taste, smell, and touch. Of music he was passionately fond, and in colour he had more than a painter's joy. As to taste, Haydon tells of once seeing him cover his tongue with cayenne pepper, in order, as he said, that he might enjoy the delicious sensation of a cold draught of claret after it. 'Talking of pleasure,' he says in one of his letters, 'this moment I was writing with one hand, and with the other was holding to my mouth a nectarine;' and there on he proceeds to describe the nectarine in a way which might cause a sympathetic mouth to water with desire. In his Ode to the Nightingale, these lines will be remembered: O for a draught of vintage, that bath been Cooled a long age in the deep delved earth; Tasting of Flora and the country green, Dance, and Provencal song, and sun burnt mirth! 0 for a beaker full of the warm South, Full of the true, the blushful Hippocrene, With beaded bubbles winking at the brim, And purple stained mouth; That I might drink, and leave the world unseen, And with thee fade away into the forest dim. Observe how every line turns on sensuous delight. With this key, it is truly interesting to examine the poems of Keats, and find how it opens their meaning and reveals their author. In this respect, Keats was the antipodes of Shelley, whose verse is related to mental far more than sensuous emotions. In 1820, pulmonary consumption appeared in the hitherto healthy constitution of Keats. Getting into bed one night, he coughed, and said: 'That is blood bring me the candle;' and after gazing on the pillow, turning round with an expression of sudden and solemn calm, said: I know the colour of that blood, it is arterial blood I cannot be deceived in that colour; that drop is my death warrant. I must die! He passed through the alternations common to consumptive patients sometimes better and sometimes worse. His mind, at the same time, was torn with passion and anxiety. His inheritance of £2000 was gone, and he had abandoned the idea of being a surgeon. He was deeply in love, but he had no means of maintaining a wife. A brief and futile attempt was made to earn a living by writing for the magazines. Meanwhile his disease made rapid progress. Accompanied by Mr. Severn, a young friend and artist, by whom he was tended with most affectionate care, he set out to spend the winter in Italy. His sufferings, physical and mental, were intense. A keen sorrow lay in the thought that he had done nothing worthy of abiding fame. 'Let my epitaph be,' said he: 'Here lies one whose name was writ in water.' He died at Rome in the arms of Severn on the 27th of February 1821, aged twenty five years and four months. His last words were: 'Thank God, it has come!' His body was interred in the Protestant cemetery at Rome; a beautiful spot, where violets and daisies blow the winter through, and, in the words of Shelley, 'making one in love with death, to think one should be buried in so sweet a place.' Hither, a few months later, were Shelley's own ashes brought to rest under a stone hearing the inscription: 'Car Cordium.' SIR WALTER RALEIGHTo trace the career of Sir Walter Raleigh, and extricate his character from the perplexing confusion of contemporary opinion, is an undertaking of considerable difficulty. One principal cause of this is to be found in the heterogeneous qualities of the man. Soldier and poet, sailor and historian, court favourite and roving adventurer, his biographers have been at a loss under what category to place him. He was, says the writer of a little book, printed in London in 1677, and entitled The Life of the Valiant and Learned Sir Walter Raleigh, Knight, with his Tryal at Winchester, statesman, seaman, soldier, chemist, chronologer. 'He seemed to be born to that only which he went about, so dexterous was he in all his undertakings, in court, in camp, by sea, by land, with sword, with pen.' Although Raleigh exerted himself so much in the service of his country, what he did was, for the most part, so out of the way of ordinary men's doings, that even history seems perplexed to discover what to record of him. We are told how he won Elizabeth's favour at the first by laying his rich cloak in the mire to save her majesty's slippers. We are told how he wrote one line of a couplet, when growing restless with the dilatory manner which the queen had in promoting her favourites, and that the queen herself deigned to complete it. We are told how he introduced the poet Spenser to the court, and quarrelled with Essex. Such trivial glimpses as these are almost all we get of him. The little book above mentioned, by the way, gives a different edition of the far famed couplet to the one we have been used to. We quote the account given: ' To put the queen in remembrance, he wrote in a window obvious to her eye: Fain would I climb, yet fear I to fall. Which her majesty, either espying or being shewn, under wrote this answer: If thy heart fail thee, climb not at all. Raleigh feared no man and no quarrel, and stood his ground against all. He was no sycophant. He must have had a clever wit, joined with his manliness and impetuosity, for he managed to retain Elizabeth's good graces to the last; while the less fortunate Essex died on the scaffold. Raleigh had a restless spirit, which made him at once innovator and adventurer. He was always making new discoveries. In his dress he was singular, his armour was a wonder, his creed his own concocting. He it was who introduced tobacco; which Elizabeth, strangely enough, judging merely in a commercial spirit, regarded as a useful article, but which seemed to James an execrable nuisance. The El Dorados which he went in search of were innumerable; and as he joined with these mine finding expeditions a large amount of carrack stopping, he won himself at last the characteristic appellation of The Scourge of Spain, and for this Spain, relentless, had his head in the end. The day of Elizabeth's death was the birthday of Raleigh's misfortunes. He never was a favourite with James from the first. It is not long before we find him brought up for trial for high treason, in what has always been called Raleigh's Conspiracy so called, it may be, because Raleigh had the least to do with it of all of those involved; or perhaps, which is more likely, because it was a puzzle to every one how such a man as Raleigh could have been connected with it. Having been previously examined in July, Raleigh was brought to trial at Winchester, on November 17, 1603. Throughout the whole, he is described as conducting himself with spirit, as rather shewing love of life than fear of death,' and replying to the insulting language of Sir Edward Coke, the king's attorney, with a dignity which remains Coke's lasting reproach. Coke's unprovoked insults were abominable. He called Raleigh, for instance, 'the absolutest traitor that ever was.' To which Raleigh only rejoined: 'Your phrases will not prove it, Mr. Attourney.' What a speech was this for the king's advocate: Thou bast a Spanish heart, and thyself art a spicier of hell! The following is a specimen of the style of bickering which went on on the occasion: Raleigh. I do not hear yet that you have spoken one word against me; here is no treason of mine done. If my Lord Cobham be a traitor, what is that to me? Coke. All that he did was by thy instigation, thou viper; for I thou thee, thou traitor. Raleigh. It becometh not a man of quality and virtue to call me so: but I take comfort in it, it is all you can do. Coke. Have I angered you? Raleigh. I am in no case to be angry. Here Lord Chief Justice Popham seems ashamed, and puts in an apology for his friend on the king's side: Sir Walter Raleigh, Mr. Attourney speaketh out of the zeal of his duty for the service of the king, and you, for your life: be valiant on both sides.' [A curious observation!] In one instance, Coke was so rude that Lord Cecil rose and remarked: 'Be not so impatient, Mr. Attourney, give him leave to speak.' And so we are informed: Here Mr. Attourney sat down in a chafe, and would speak no more, until the commissioners urged and entreated him. After much ado he went on, &c. Raleigh had but one real witness against him, and that was Lord Cobham, the head of the plot, and Raleigh's personal friend. It seems that Cobham, in a temporary fit of anger Raleigh seems to have inculpated him in the first instance described Raleigh as the instigator of the whole business. Coke produced a letter, written by Cobham, which seemed to enclose the matter in a nut shell, for it was very explicit against Raleigh. Raleigh pleaded to have Cobham produced in court, but this was refused. Raleigh had his reasons for this, for at the last minute he pulled out a letter, which Cobham had written to him since the one to Coke, in which that lord begged pardon for his treachery, and declared his friend innocent. And so it appeared that he was, although he evidently had more knowledge of matters than was good for his safety. But a minor point, which was brought forward at last, was like the springing of a mine, and spoiled Raleigh's case. It affirmed that Sir Walter Raleigh had been dealt with to become a spy of Spain, at a pension of £1500 per annun. This might have been a trap set by Spain, but, at anyrate, Raleigh did not deny the fact, and so the evidence turned against him. He was sentenced, with disgraceful severity, to be hanged, drawn, and quartered. Raleigh wrote a letter to his wife, while in expectation of death. A private communication like this letter gives us a better insight into his conscience, and also into his so called 'atheism,' than could be got from any other source I sued for my life, but (God knows) it was for you and yours that I desired it: for know it, my dear wife, your child is the child of a true man, who, in his own respect, despiseth death and his misshapen and ugly forms. I cannot write much. God knows how hardly I steal this time when all sleep, and it is also time for me to separate my thoughts from the world. Beg my dead body, which living was denied you, and either lay it in Sherburn or in Exeter Church, by my father and mother.' [Is not this the last wish of all rovers?] 'I can say no more, time and death calleth me away. The everlasting God, powerful, infinite, and inscrutable God Almighty' [Has this an atheistic sound?], who is goodness itself, the true Light and Life, keep you and yours, and have mercy upon me, and forgive my persecutors and false accusers [Why, this is very Christianity!], and send us to meet in his glorious kingdom! My dear wife, farewell, bless my boy, pray for me, and let my true God hold you both in his arms. Yours that was, but now not my own, After all, Raleigh was not executed. He lived yet a dozen years a prisoner in the Tower, his wife with him, and wrote his famous History of the World. When he could no longer rove over the whole earth, he set himself to write its history. He won the friendship of Prince Henry, who could never understand how his father could keep so fine a bird in a cage; and had the young prince lived, he would have set the bird at liberty, but he died. At length James released Raleigh, and sent him on one more mining expedition to South America, with twelve ships and abundance of men. But secretly, out of timidity, James informed Spain of the whole scheme, and the expedition failed. A town was burned, and the Spanish ambassador, Gondomar, became furious. Raleigh knew what to expect; but, having bound himself to return, he did return. He was immediately seized; and, without any new trial, was beheaded on his old condemnation, all to appease the anger of Spain, upon Thursday, the 29th of October 1618, in Old Palace Yard, Westminster. Raleigh died nobly. The bishop who attended him, and the lords about him, were astonished to witness his serenity of demeanour. He spoke to the Lord Arundel to desire the king to allow no scandalous writings, defaming him, to be written after his death the only one which was written, strange to say, was James's Apology and he observed calmly: I have a long journey to go, therefore must take leave! He fingered the axe with a smile, and called it a sharp medicine, a sound cure for all diseases; and laid his head on the block with these words in conclusion: So the heart be right, it is no matter which way the head lies. Thus, says our little book, died that knight who was Spain's scourge and terror, and Gondomar triumph; whom the whole nation pitied, and several princes interceded for; Queen Elizabeth's favourite, and her successor's sacrifice. A person of so much worth and so great interest, that King James would not execute him without an apology; one of such incomparable policy, that he was too hard for Essex, was the envy of Leicester, and Cecil's rival, who grew jealous of his excellent parts, and was afraid of being supplanted by him. The following is Raleigh's last poem, written the night before his death, and found in his Bible, in the Gate house, at Westminster: SIR W. RALEIGH THE NIGHT BEFORE HIS DEATH Even such is time, which takes in trust Our youth, our joys, and all we have, And pays us nought but age and dust; Which in the dark and silent grave, When we have wandered all our ways, Shuts up the story of our days! And from which grave, and earth, and dust, The Lord shall raise me up, I trust. THE HERMIT OF GRUB STREETAmongst the many histories of extraordinary characters, who from various motives have secluded themselves from the world, probably few have created more interest than Mr. Henry Welby, the individual about to be recorded. He was a native of Lincolnshire, where, in the neighbourhood of Grantham, his descendants still live. The family is ancient, and of high position, as may be inferred from several of its members having sat in parliament for the county of Lincoln, in the times of the Henrys and the Edwards, and from others having filled the post of sheriff an office in those days held only by men of the highest status. About the time of the accession of Queen Elizabeth, we find Mr. Henry Welby residing at Goxhill, an ancient village near the Lincolnshire bank of the river Humber, nearly opposite to Kingston upon Hull. He was the inheritor of a considerable fortune, and all accounts that have been published. concerning him, represent him as a highly accomplished, benevolent, and popular gentleman. In this neighbourhood, he seems to have lived for a number of years, and then to have quitted it to reside in London, under the singular circumstances now to be detailed, as related in a curious work, published in 1637, under the following title: The Phoenix of these late Times; or the Life of Henry Welby, Esq., who lived at his House, in Grub Street, Forty four years, and in that Space was never seen by any: And there died, Oct. 29, 1636, aged Eighty four. Shewing the first Occasion and Reason thereof. With Epitaphs and Elegies on the late Deceased Gentleman; who lyeth buried in St. Giles' Church, near Cripplegate, London. In the preface to this singular pamphlet, the following passage occurs: This gentleman, Master Henry Welby, was forty years of age before he took this solitary Life. Those who knew him, and were conversant with him in his former time, do report, that he was of a middle stature, a brown complexion, and of a pleasant chearful countenance. His hair (by reason no barber came near him for the space of so many Years) was much overgrown; so that he, at his death, appeared rather like a Hermit of the Wilderness, than inhabitant of a city. His habit was plain, and without ornament; of a sad coloured cloth, only to defend him from the cold, in which there could be nothing found either to express the least imagination of pride or vain glory.' The various accounts which have been published of this remarkable man, agree in the main, but differ in one or two particulars. For instance, in one it is stated that it was his brother, whose conduct led to the strange results recorded; and, in another, that it was merely a kinsman. In the present notice, we have adhered to the narrative given to the world in 1637. It thus records history of Mr. Welby's eccentricities. The occasion was the unkindness, or the unnaturalness and inhumanity of a younger brother, who, upon some discontent or displeasure conceived against him, rashly and resolutely threatened his death. The two brothers meeting face to face, the younger drew a pistol, charged with a double bullet, from his side, and presented upon the elder, which only gave fire, but by the miraculous providence of god, no farther report. At which the elder, seizing him, disarmed him of his tormenting engine, and so left him; which, bearing to his chamber, and desiring to find whether it was merely a false fire to frighten him, or a charge speedily to dispatch him, he found bullets, and thinking of the danger he had escaped, fell into many deep considerations. He then grounded his irrevocable resolution to live alone. He kept it to his dying day.  That he might the better observe it, he took a very fair House in the lower end of Grub street, near unto Cripplegate, and having contracted a numerous retinue into a small and private Family, having the house before prepared for his purpose, he entered the door, chasing to himself, out of all the rooms, three private chambers best suiting with his intended solitude; the first for his diet, the second for his lodging, and the third for his study one within another. While his diet was set on the table by one of his servants an old maid he retired into his lodging chamber; and while his bed was making, into his study; and so on, till all was clear. And there he set up his rest, and in forty four years never, upon any occasion how great soever, issued out of those chambers, till he was borne thence upon men's shoulders; neither in all that time did son in law, daughter, grandchild, brother, sister, or kinsman, stranger, tenant, or servant, young or old, rich or poor, of what degree or condition soever, look upon his face, saving the ancient maid, whose name was Elizabeth, who made his fire, prepared his bed, provided his diet, and dressed his chamber; which was very seldom, or upon an extraordinary necessity that he saw her; which maid servant died not above six days before him. In all the time of his retirement he never tasted fish nor flesh. He never drank either wine or strong water. His chief food was oatmeal boiled with water, which some people call gruel; and in summer, now and then, a salad of some cool, choice herbs. For dainties, or when he would feast himself, upon a high day, he would eat the yoke of a hen's egg, but no part of the white; and what bread he did eat, he cut out of the middle part of the loaf, but of the crust he never tasted; and his continual drink was four shilling beer, and no other; and now and then, when his stomack served him, he did eat some kind of suckers; and now and then drank red cow's milk, which Elizabeth fetched for him out of the fields, hot from the cow; and yet he kept a bountiful table for his servants, with entertainment sufficient for any stranger, or tenant, who had occasion of business at his house. In Christmas holidays, at Easter, and upon other festival days, he had great cheer provided, with all dishes seasonable with the times, served into his own chamber, with store of wine, which his maid brought in; when he himself would pin a clean napkin before him, and putting on a pair of white Holland sleeves, which reached to his elbows, called for his knife, and cutting dish after dish up in order, send one to one poor neighbour, the next to another, &c., whether it were brawn, beef, capon, goose, &c., till he had left the table quite empty. Then would he give thanks, lay by his linen, put up his knife again, and cause the cloth to be taken away; and this would he do, dinner and supper, without tasting one morsel himself; and this custom he kept to his dying day! Indeed, he kept a kind of continual fast, so he devoted himself unto continual prayer, saving those seasons which he dedicated to his study; for you must know that he was both a scholar and a linguist; neither was there any author worth the reading, either brought over from beyond the seas, or published here in the kingdom, which he refused to buy, at what dear rate soever; and these were his companions in the day, and his counsellors in the night; insomuch that the saying may be verified of him nacnquam minus solos, quam cunt solus. He was never better accompanied, or less alone, than when alone. Out of his private chamber, which had a prospect into the street, if he spied any sick, weak, or lame, would presently send after them, to comfort, cherish, and strengthen them; and not a trifle to serve them for the present, but such as would relieve them many days after. He would, more over enquire what neighbours were industrious in their callings, and who had great charge of children; and if their labour or industry could not sufficiently supply their families, to such he would liberally send, and relieve them according to their necessities.' Taylor, the 'Water Poet,' thus commemorates the recluse of Grub Street: Old Henry Welby well be f thou for ever, Thy Purgatory 's past, thy Heaven ends never. Of eighty four years' life, full forty four Man saw thee not, nor e'er shall see thee more. 'Twas Piety and Penitence caus'd thee So long a Pris'ner (to thyself) to be: Thy bounteous House within express'd thy Mind; Thy Charity without, the Poor did find. From Wine thou wast a duteous Rechabite, And Flesh so long Time shunn'd thy Appetite: Small Beer, a Candle, Milk, or Water gruel, Strengthen'd by Grace, maintain'd thy daily Duell 'Gainst the bewitching World, the Flesh, the Fiend, Which made thee live and die well: there's an End. A more recent work gives us the information, that Mr. Welby had an only child, a daughter, who was married to Sir Christopher Hildyard, Knight of Winstead, in Yorkshire, and left three sons: 1. Henry, who married Lady Anne Leke, daughter of Francis, first Earl of Scarborough; and of this marriage the late Right Hon. Charles Tennyson D'Eyncourt is a descendant. 2. Christopher. 3. Sir Robert Hildyard, an eminent royalist commander, who, for his gallant services, was made a knight banneret, and afterwards a baronet. |