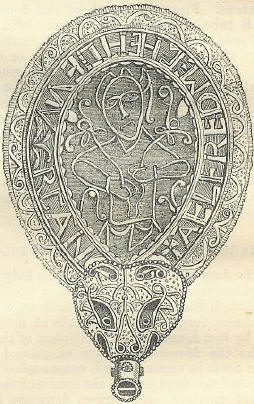

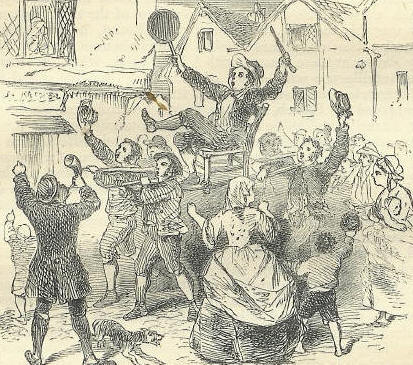

28th OctoberBorn: Desiderius Erasmus, distinguished scholar and writer, 1467, Rotterdam; Dr. Nicholas Brady, versifier of the Psalms, 1659, Bandon, Cork; Sir David Dalrymple, Lord Hailes, historical writer, 1726, Edinburgh; Emanuel, Marshal Grouchy, Bonapartist commander, 1766, Paris. Died: Maxentius, Roman emperor, drowned in Tiber, 312; Alfred the Great, king of England, about 900, Winchester; Michael is Tellier, chancellor of France, 1685, Paris; John Wallis, eminent mathematician, 1703, Oxford; John Locke, philosopher, 1704, Oates, Essex; Prince George of Denmark, husband of Queen Anne of England, 1708; John Smeaton, engineer, 1792, Austhorpe, near Leeds; Charlotte Smith, novelist, 1806, Tilford, Surrey. Feast Day: St. Simon the Canaanite, apostle. St. Jude, apostle. St. Faro, bishop of Meaux, confessor, 672. St. Neot, anchoret and confessor, 9th century. ERASMUSThough professedly an adherent of the ancient faith, Erasmus must be regarded as one of the most influential pioneers of the Reformation. His Colloquies and Encomium Moritz, or Praise of Folly, in which the superstitions of the day, and the malpractices of priests and friars, are exposed in the wittiest and most ludicrous manner, found thousands of admirers who were unable to appreciate the subtleties of dogmatic theology. It was pithily said of him, that he laid the egg which Luther hatched. Erasmus was the natural son of a Dutchman, called Gheraerd or Garrit, a name having the same signification as the Amiable or the Beloved; and from this circumstance he assumed the designation of Desiderius Erasmus, which, by reduplication, expresses the same meaning in the Latin and Greek languages. He was educated for the Roman Catholic Church, and entered for a time the monastery of Emaus, near Gouda, but found such a profession very uncongenial, and as he had already given great promise of mental vigour and acumen, he obtained a dispensation from his monastic vows, and travelled through different parts of Europe. While thus journeying from place to place, he supported himself by lecturing and taking charge of pupils, one of whom was Alexander Stuart, a natural son of James IV of Scotland, who was afterwards slain with his father at Flodden. Among other countries visited by Erasmus was England, where he resided in the house of Sir Thomas More, and also acted for a time as professor of divinity at Cambridge. He afterwards passed over to the Low Countries on an invitation from the Archduke Charles, afterwards Charles V, by whom he was invested with the office of councillor, and a salary of two hundred florins. In 1516, he published his celebrated edition of the Greek Testament, with notes, being the first version which appeared in print. By many this is regarded as the greatest work of Erasmus, who was both an excellent Greek scholar and one of the principal revivers of the study of that ancient language in Western Europe. In 1521, he took up his residence at Basel, where, in the following year, his celebrated Colloquies were published. From this he removed in 1529 to Freiburg, but returned again in 1535. He died at Basel on 12th July 1536. Though a kind hearted generous minded man, Erasmus had little of the hero or martyr in his composition, and however clearly his excellent judgment might enable him to form certain conclusions, he wanted still the courage and self denial to carry them into practice. His indecision in this respect furnished Luther with materials for the most cutting and contemptuous sarcasm. Indeed, in one of his own letters, Erasmus states very candidly his timorous character as follows: 'Even if Luther had spoken everything in the most unobjectionable manner, I had no inclination to die for the sake of truth. Every man has not the courage to make a martyr; and I am afraid, if I were put to the trial, I should imitate St. Peter.' He may be regarded in the light of an accomplished, ease loving scholar, latitudinarian on the subject of religion, and neither disposed to sympathise with the despotism and burdensome ordinances of the old faith, or the austerities and fiery zeal of the new. It is stated, however, that the friends in whose arms he expired were Protestants, and that, in his dying moments, he commended himself to God and Christ alone, rejecting all the ceremonies of the Romish Church. THE ALFRED JEWELIt may well be said, that of the many monarchs who have been endowed with the appellation Great, Alfred of England was one of the very few who really merited the distinguished title. The materials for his history are indeed scanty, yet they teem with romance of the highest and most instructive character namely, that which represents a good man heroically contending with the greatest difficulties, until, by energy and perseverance, he ultimately overcomes them. His desperate conflicts with the invading Danes, and the various fortunes of the respective parties; Alfred's magnanimity and prudence, whether as conqueror or fugitive; his attachment to literature and the arts; his unwearied zeal to promote the moral, social, and political progress of his subjects all make even the minutest details of his history of surpassing interest to all educated Britons.  The remarkable jewel, represented in the engraving, was found, in 1693, at Newton Park, a short distance north of the site of Ethelney Abbey, in Somersetshire, near the junction of the rivers Parret and Thone. It is now preserved in the Ashmolean Museum, at Oxford; and, independent of its bearing the name of Alfred, is a most interesting specimen of Anglo Saxon art. The inevitable melting pot has left few similar specimens of that age, but we know there must have been many, for the business of a goldsmith was held in high repute by the Anglo Saxons, and a poem in that language, on the various conditions of men, contains lines that may be translated thus: For one a wondrous skill in goldsmith's art is provided, full oft he decorates and well adorns a powerful king's noble, and he to him gives broad land in recompence. Asser, the friend and biographer of Alfred, informs us that, when the great monarch had secured peace and protection to his subjects, he resolved to extend among them a knowledge of the arts. For this purpose he collected, from many nations, an almost innumerable multitude of artificers, the most expert in their respective trades. Among these were not a few workers in gold and silver, who, acting under the immediate instructions of Alfred, executed, with incomparable skill, many articles of these metals. From the circumstance of the jewel having inscribed on it, in Saxon characters, Ælfred are had gewercan (Alfred had me wrought), we may reasonably conclude that it was made under his own superintendence; arid further, from its richness of workmanship and material, that it was a personal ornament worn by the good king himself. The lower end of the jewel, as represented in the engraving, is formed into the head of a griffin, a national emblem of the Saxons. From the mouth of this figure issues a small tube, crossed in the interior by a minute pin of gold. The latter is evidently intended to connect the ornament with the collar or hand by which it was suspended round the neck; the general flatness of form indicating that it was worn in that manner. Antiquaries have not agreed as to the person represented on one side of the jewel. Some have supposed it to be the Saviour, others St. Cuthbert, or Pope Martin. But the opinion, that it represented. Alfred himself, symbolising his kingly office, is as general and tenable as any yet advanced upon the subject. CHARLOTTE SMITH: FLORA'S HOROLOGEIn the days of our grandfathers, this lady enjoyed a considerable reputation, both as a novelist and poet, though her lucubrations in both capacities are now almost forgotten. Two works of fiction composed by her, Emmeline, or the Orphan of the Castle, and the Old Manor House, are mentioned by Sir Walter Scott in terms of high commendation. An ill assorted marriage proved the source of an infinite series of troubles, and various domestic bereavements, combined latterly with bodily infirmities, saddened an existence which, during the greater part of its course, was more characterised by clouds than sunshine. The annexed poem exhibits a pleasing specimen of Mrs. Smith's talents, and is here introduced as apposite to the character of the Book of Days, presenting, as it does, the idea of a clock or dial of Flora. The phenomenon of the sleep of plants, or the closing and reopening of the petals of flowers at certain hours, was, as is well known, the discovery of the great botanist Linnaeus. FLORA'S HOROLOGE In every copse and sheltered dell, Unveiled to the observant eye, Are faithful monitors, who tell How pass the hours and seasons by. The green robed children of the spring Will mark the periods as they pass, Mingle with leaves Time's feathered wing, And bind with flowers his silent glass. Mark where transparent waters glide, Soft flowing o'er their tranquil bed; There, cradled on the dimpling tide Nymphaea rests her lovely head. But conscious of the earliest beam, She rises from her humid nest, And sees reflected in the stream The virgin whiteness of her breast. Till the bright Daystar to the west Declines, in ocean's surge to lave; Then, folded in her modest vest, She slumbers on the rocking wave. See Hieraciums' various tribe, Of plumy seed and radiate flowers, The course of Time their blooms describe, And wake or sleep appointed hours. Broad o'er its imbricated cup The Goatsbeard spreads its golden rays, But shuts its cautious petals up, Retreating from the noontide blaze. Pale as a pensive cloistered nun, The Bethlehem Star her face unveils, When o'er the mountain peers the sun, But shades it from the vesper gales. Among the loose and arid sands The humble Arenaria creeps; Slowly the Purple Star expands, But soon within its calyx sleeps. And those small bells so lightly rayed With young Aurora's rosy hue, Are to the noontide sun displayed, But shut their plaits against the dew. On upland slopes the shepherds mark The hour, when, as the dial true, Cichorium to the towering lark Lifts her soft eyes serenely blue. And thou, 'wee crimson tipped flower,' Gatherest thy fringed mantle round Thy bosom, at the closing hour, When night drops bathe the turfy ground. Unlike Silene, who declines The garish noontide's blazing light; But when the evening crescent shines, Gives all her sweetness to the night. Thus in each flower and simple bell, That in our path betrodden lie, Are sweet remembrancers who tell How fast the winged moments fly. SCHINDERHANNES ('JOHN, THE SCORCHER ')At the close of the last century, and the beginning of the present, the borderland between France and Germany was infested by bands of desperadoes, who were a terror to all the peaceful inhabitants. War, raging with great fury year after year, had brought the Rhenish provinces into a very disorganised state, which offered a premium to every species of lawless violence. Bands of brigands roamed about, committing every kind of atrocity. They were often called Chauffeurs or Scorchers; because they were accustomed to hold the soles of their victims' feet in front of a fierce fire, to extort a revelation of the place where their property was concealed. Sometimes they were called Garotters or Stranglers (from garrot, a stick which enabled the strangler to twist a cord tightly round the neck of his victim). Each band had a camp or rendezvous, with lines of communication throughout a particular district. The posts on these lines were generally poor country taverns, the landlords of which were in league with the band. And not only was this the case, but from Holland to the Danube, the chauffeurs could always obtain friendly shelter at these houses, with means for exchanging intelligence with others of the fraternity. The brigands concocted for their own use a jargon composed of French, German, Flemish, and Hebrew, scarcely intelligible to other persons. Not unfrequently, magistrates and functionaries of police were implicated with this confederacy. Names, dress, character, complexion, and feature were changed with wonderful ingenuity by the more accomplished leaders; and women were employed in various ways requiring tact and finesse. The more numerous members of the band, rude and brutal, did the violent work which these leaders planned for them. Many, called apprentices, inhabited their own houses, worked at their own trades, but yet held themselves in readiness, at a given signal understood only by themselves, to leave their homes, and execute the behests of the leaders. They were bound by oaths, which were rarely disregarded, an assassin's poniard being always ready to avenge any violation. Most of these apprentices were sent to districts far removed from their homes when lawless work was to be done. A Jewish spy was generally concerned in every operation of magnitude: his vocation was to pick up information that would be useful to the robber chief, concerning the amount and locality of obtainable booty. For his information, he received a stipulated fee, and then made a profit out of his purchase from the robbers of the stolen property. Schinderhannes, or 'John the Scorcher,' was the most famous of all the leaders of these robbers. His real name was Johann Buckler; but his practice of chauffage, or scorching the feet of his victims, earned for him the appellation of Schinderhannes. Born in 1779, near the Rhine, he from early years loved the society of those who habitually braved all law and control. As a boy, he joined others in stealing meat and bread from the commissariat-wagons of the French army at Kreuznach. He joined a party of bandits, and was continually engaged in robberies: he was often captured, but as frequently escaped with wonderfulingenuity, and his audacity soon led to his being chosen captain of a band. There was something in his manner which almost paralysed those whom he attacked, and rendered them powerless against him. On one occasion, when alone, he met a large party of Jews travelling together. He ordered them imperiously to stop, and to bring him their purses one by one, which they did. He then searched all their pockets; and, finding his carbine in the way, told one of the Jews to hold it for him while he rifled their pockets! This also was done, and the carbine handed to him again. Sometimes he would summon a farmer or other person to his presence, and tell him to bring a certain sum of money, as a ransom, or purchase price of safety in advance; and such was the terror at the name of Schinderhannes, that these messages were rarely disregarded. As the French power became consolidated on the left bank of the Rhine, Schinderhannes found it expedient to limit his operations to the right bank; and the prisons of Coblentz and Cologne were filled with his adherents. Like Robin Hood, he often befriended the poor at the expense of the rich; but, unlike the hero of Sherwood Forest, he was often cruel. The career of Schinderhannes virtually terminated on the 31st of May 1802, when he was finally captured near Limburg; but his actual trial did not take place till the closing days of October 1803, when evidence sufficient was brought forward to convict him of murder, and he was condemned to death. Mr. Leitch Ritchie has made this redoubtable bandit the hero of a romance Schinderhannes, the Robber of the Rhine. In his Travelling Sketches on the Rhine, and in Belgium and Holland, he has also given some interesting details concerning Schinderhannes himself, and the chauffeurs generally. Among many so called wives, one named Julia was especially beloved by him, and she and a brother robber named Fetzer, were with him when captured. 'At his trial,' says Mr. Ritchie in the second of the above named works, 'he was seen frequently to play with his young infant, and to whisper to his wife, and press her hands. The evidence against him was overpowering, and the interest of his audience rose to a painful pitch. When the moment of judgment drew near, his fears for Julia shook him like an ague. He frequently cried out, clasping his hands: She is innocent! The poor young girl is innocent! It was I who seduced her! Every eye was wet, and nothing was heard in the profound silence of the moment, but the sobs of women. Julia, by the humanity of the court, was sentenced first; and Schinderhannes embraced her with tears of joy when he heard that her punishment was limited to two years' confinement. His father received twenty two years' of fetters; and he himself, with nineteen of his band, was doomed to the guillotine. The execution took place on the 21st of November 1803, when twenty heads were cut off in twenty six minutes. The bandit chief preserved his intrepidity to the last.' Concerning the chauffeurs or bandits generally, it may suffice to say that when Bonaparte became First Consul, he determined to extirpate them. One by one the miscreants fell into the hands of justice. For many years the alarmists in France had been in the habit of insinuating that the bandits were prompted by the exiled royalists, or by the English; but it was perfectly clear that they needed no external stimulus of this kind. After the death of Schinderhannes, the bands quickly disappeared. 'RIDING THE STANG;' OR 'ROUGH MUSIC'Punishments for minor offences were formerly designed to produce shame in the delinquents by exposing them to public ridicule or indignation. With this view, the execution of the punishment was left very much in the hands of the populace. Such was the practice in the case of the kaiaks, the dunking stool, the whirligig, the drunkard's cloak, the stocks, the pillory, &c., all of which have been either legally abolished or banished by the progress of civilisation. There is, however, one species of punishment belonging to the above category, which the people seem determined to retain in their own hands, and enforce whenever they judge it expedient so to do. It was exercised, to the knowledge of the writer, on the 28th of October, and ten following days, Sunday excepted, in the year 1862. The punishment in question, called in the north of England 'Riding the Stang,' and in the south 'Rough Music,' is not noticed in the Popular Antiquities by Bourne and Brand, but is of frequent occurrence in most of our English counties. If a husband be known to beat his wife, or allow himself to be hen pecked if he be unfaithful to her, or she to him the offending party, if living in a country village, will probably soon be serenaded with a concert of rough music. This harmonious concert is produced by the men, women, and children of the village assembling together, each provided with a suitable instrument. These consist of cows horns, frying pans, warming pans, and tea kettles, drummed on with a large key; iron pot lids, used as cymbals; fire shovels and tongs rattled together; tin and wooden pails drummed on with iron pokers or marrow bones in fact, any implement with which a loud, harsh, and discordant sound can be produced. Thus provided, the rustics proceed to the culprit's house, and salute him or her with a sudden burst of their melodious music, accompanied with shouts, yells, hisses, and cries of 'Shame! shame! Who beat his wife? I say, Tom Brown, come out and shew yourself!' and all such kind of taunts and ridicule as rustic wit or indignation can invent. The village humorist, often with his face blacked, or coloured with chalk and reddle, and his body grotesquely clothed and decorated, acts the part of herald, and, in all the strong savour of rustic wit and drollery, proclaims the delinquencies of the unhappy victim or victims. The proclamation, of course, is followed by loud bursts of laughter, shouts, yells, and another tremendous serenade of `rough music,' to the melody of which the whole party march off, and proceed through the village, proclaiming in all the most public parts the 'burden of their song.'  This hubbub is generally repeated every evening, for a week or a fortnight, and seldom fails to make a due impression on the principal auditor; for 'Music bath charms to soothe the savage breast;' and the writer can testify that, at least in one instance, where police and magistrates had tried in vain to reform a brutal husband who had beaten and ill treated his wife, his savage breast was tamed by the magic strains of 'rough music.' He was never known to beat his wife again, and acknowledged that the sound of that music never ceased to 'charm' his waking thoughts, and too often formed 'the melody of his dreams.' In the northern counties, this custom, as before mentioned, is called 'riding the stang,' because there, in addition to rough music, it is the practice to carry the herald. astride on a stag the north country word for pole or in a chair fastened on two poles, to make him more conspicuous. He is, too, always provided with a large frying pan and key or hammer, and, after beating them together very vigorously, makes his proclamation in rhyme, using the following words, varied only to suit the nature of the offence: Ran, tan, tan; ran, tan, tan, To the sound of this pan This is to give notice that Tom Trotter Has beaten his good woman! For what, and for why? 'Cause she ate when she was hungry, And drank when she was dry. Ran, tan, ran, tan, tan; Hurrah hurrah! for this good woman! He beat her, he beat her, he beat her indeed, For spending a penny when she had need. He beat her black, he beat her blue; When Old Nick gets him, he'll give him his due; Ran, tan, tan; ran, tan, tan; We'll send him there in this old frying-pan; Hurrah hurrah! for his good woman. The 'ran tan' chorus is shouted by the whole crowd, and repeated after every line. The practice is varied in different places by the addition of an effigy of the culprit riding on an ass, with his face towards the tail, and by other freaks of local humour, suggested perhaps by some peculiarity of the occasion. This mode of manifesting the popular feeling was in vogue when Hudibras was written; and though then often including additions better omitted, was observed in other respects much as at the present day: And now the cause of all their fear By slow degrees approached so near, They might distinguish different noise Of horns and pans, and dogs and boys, And kettle drums, whose sullen dub Sounds like the hooping of a tub; And followed with a world of tall lads, That merry ditties troll'd, and ballads. Next pans and kettles of all keys, From trebles down to double base; And at fit periods the whole rout Set up their throats with clamorous shout. Such ceremonies as we have above described are known on the continent by the name of the Charivari, and also of Katzenmusik (Anglicé, caterwauling). Latterly, in France, the charivari took a political turn, and gave name to a satirical publication established in Paris in 1832. The same title, as all our readers know, was adopted as an accessory designation by the facetious journalist, Mr. Punch. |