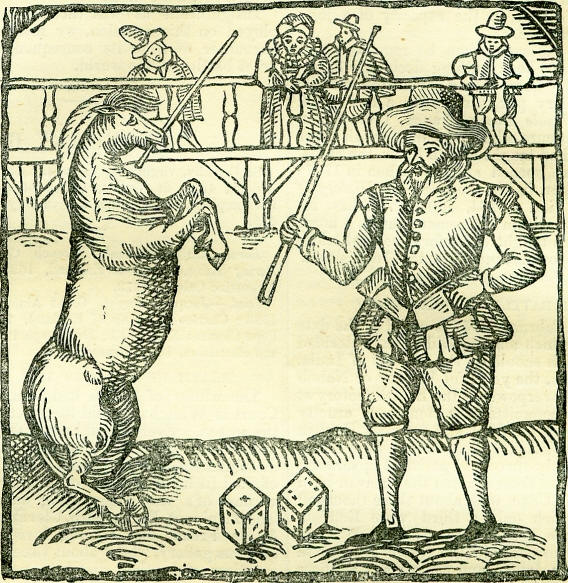

5th FebruaryBorn: Bishop Thomas Tanner, 1674 (N. S.), Market Lavington; Rev. Dr. John Lingard, historian, 1771, Winchester; Sir Robert Peel, Bart., statesman, 1788, Burg, Lancashire; Dr. John Lindley, botanist, 1799, Catton. Died: Marcus Cato, B.C. 46, Utica; James Meyer, Flemish scholar, 1552; Adrian Reland, Orientalist and scholar, 1718, Utrecht; James, Earl Stanhope, political character, 1721, Chevening; Dr. Cullen, 1790, Kirknewton; Lewis Galvani, discoverer of galvanism, 1799, Bologna; Thomas Banks, sculptor, 1805; General Paoli, Corsican patriot, 1807. Feast Day: St. Agatha, virgin martyr, patroness of Malta, 251. The martyrs of Pontus, 304. St. Abraamius, bishop of Arbela, martyr, 348. St. Avitus, archbishop of Vienne, 525. St. Alice (or Adelaide), abbess at Cologne, 1015. The twenty-six martyrs of Japan, 1697. DEATH OF THE FIRST EARL STANHOPEThis eminent person carried arms under King William in Flanders; and his Majesty was so struck with his spirit and talent that he gave him a captain's commission in the Foot Guards, with the rank of lieutenant-colonel, he being then in his 21st year. He also served under the Duke of Schomberg and the Earl of Peterborough; and subsequently distinguished himself as Commander-in-chief of the British forces in Spain. At the close of his military career, he became an active Whig leader in Parliament; took office under Sunderland, and was soon after raised to the peerage. His death was very sudden. He was of constitutionally warm and sensitive temper, with the impetuous bearing of the camp, which he had never altogether shaken off. In the course of the discussion on the South Sea Company's affairs, which so unhappily involved some of the leading members of the Government, the Duke of Wharton (Feb. 4th, 1721) made some severe remarks in the House of Lords, comparing the conduct of ministers to that of Sejanus, who had made the reign of Tiberius hateful to the old Romans. Stanhope, in rising to reply, spoke with such vehemence in vindication of himself and his colleagues, that he burst a blood-vessel, and died the next day. 'May it be eternally remembered,' says the British Merchant, 'to the honour of Earl Stanhope, that he died poorer in the King's service than he came into it. Walsingham, the great Walsingham, died poor; but the great Stanhope lived in the time of South Sea temptations.' GENERAL PAOLI AND DR. JOHNSONWhen, in 1769, this patriotic General, the Garibaldi of his age, was overpowered in defending Corsica against the French, he sought refuge in England, where he obtained a pension of £1200 a year, and resided until 1789. Boswell, who had travelled in Corsica, anticipated introducing him to Johnson; 'for what an idea,' says he, in his account of the island, 'may we not form of an interview between such a scholar and philosopher as Mr. Johnson, and such a legislator and general as Paoli!' Accordingly, upon his arrival in England, he was presented to Johnson by Boswell, who tells us, they met with a manly ease, mutually conscious of their own abilities, and the abilities of each other. 'The General spoke Italian, and Dr. Johnson English, and understood one another very well, with a little interpretation from me, in which I compared myself to an isthmus, which joins two great continents.' Johnson said, 'General Paoli had the loftiest port of any man he had ever seen.' Paoli lived in good style, and with him, Johnson says, in one of his letters to Mrs. Thrale, 'I love to dine.' Six months before his death, June 25, 1784, the great Samuel was entertained by Paoli at his house in Upper Seymour-street, Portman-square. 'There was a variety of dishes much to his (Johnson's) taste, of all of which he seemed to me to eat so much, that I was afraid he might be hurt by it; and I whispered to the General my fear, and begged he might not press him. "Alas!" said the General, "see how very ill he looks; he can live but a very short time. Would you refuse any slight gratifications to a man under sentence of death? There is a humane custom in Italy, by which persons in that melancholy situation are indulged with having whatever they like to eat and drink, even with expensive delicacies."' On the breaking out of the French Revolution, it was thought that Paoli, by the influence of his name with his countrymen, might assist in preserving their loyalty against the machinations of the liberals. Repairing to Paris, he was graciously received by Louis XVI, and appointed Lieutenant-General of the island. The Revolutionists were at first too much for him; but, on the war breaking out between England and France, he, with the aid of the English, drove the French garrisons out of the island. On departing soon after, he strongly recommended his countrymen to persist in allegiance to the British crown. He then returned to England, where he died February 5, 1807. A monument, with his bust by Flaxman, was raised to his memory in Westminster Abbey. THE BELL-SAVAGE INN-BANKS'S HORSEOn the 5th February, in the 31st year of Henry VI, John French gave to his mother for her life: 'all that tenement or inn, with its appurtenances, called Savage's Lin, otherwise called the Bell on the Hoop, in the parish of St. Bridget, in Fleet-street, London, to have and to hold, .... without impeachment of waste.' From this piece of authentic history we become assured of the fallacy of a great number of conjectures that have been indulged in regarding the origin of the name 'Bell and Savage,' or 'Boll-Savage,' which was for ages familiarly applied to a well-known, but now extinct inn, on Ludgate-hill. The inn had belonged to a person named Savage. Its pristine sign was a bell, perched, as was customary, upon a hoop. 'Bell Savage Inn' was evidently a mass made up in the public mind, in the course of time, out of these two distinct elements. Moth, in Love's Labour Lost, wishing to prove how simple is a certain problem in arithmetic, says, 'The dancing horse will tell you.' This is believed to be an allusion to a horse called Morocco, or Morocco, which had been trained to do certain extraordinary tricks, and was publicly exhibited in Shakspeare's time by its master, a Scotchman named Banks. The animal made his appearance before the citizens of London, in the yard of the Belle Savage Inn, the audience as usual occupying the galleries which surrounded the court in the centre of the building, as is partially delineated in the annexed copy of a contemporary wood-print, which illustrates a brochure published in 1595, under the name of Maroccu Erstatictes: or Bankes Bay Horse in a Traunce; a Discourse set downe in a merry dialogue between Bankes and his Beast ... intituled to Mine Host of the Belsauage and all his honest guests.' Morocco was then a young nag of a chestnut or bay colour, of moderate size. The tricks which the animal performed do not seem to us now-a-days very wonderful; but such matters were then comparatively rare, and hence they were regarded with infinite astonishment. The creature was trained to erect itself and leap about on its hind legs. We are gravely told that it could dance the Canaries. A glove being thrown down, its master would command it to take it to some particular person: for example, to the gentleman in the large ruff, or the lady with the green mantle; and this order it would correctly execute. Some coins being put into the glove, it would tell how many they were by raps with its foot. It could, in like manner, tell the numbers on the upper face of a pair of dice. As an example of comic performances, it would be desired to single out the gentleman who was the greatest slave of the fair sex; and this it was sure to do satisfactorily enough. In reality, as is now well known, these feats depend upon a simple training to obey a certain signal, as the call of the word Up. Almost any young horse of tolerable intelligence could be trained to do such feats in little more than a month.  Morocco was taken by its master to be exhibited in Scotland in 1596, and there it was thought to be animated by a spirit. In 1600, its master astonished London by making it override the vane of St. Paul's Cathedral. We find in the Jest-books of the time, that, while this performance was going on in presence of an enormous crowd, a serving-man came to his master walking about in the middle aisle, and entreated him to come out and see the spectacle. 'Away, you fool!' answered the gentleman; 'what need I go so far to see a horse on the top, when I can see so many asses at the bottom!' Banks also exhibited his horse in France, and there, by way of stimulating popular curiosity, professed to believe that the animal really was a spirit in equine form. This, however, had very nearly led to unpleasant consequences, in raising an alarm that there was something diabolic in the case. Banks very dexterously saved himself for this once by causing the horse to select a man from a crowd with a cross on his hat, and pay homage to the sacred emblem, calling on all to observe that nothing satanic could have been induced to perform such an act of reverence. Owing, perhaps, to this incident, a rumour afterwards prevailed that Banks and his curtal [nag] were burned as subjects of the Black Power of the World at Rome, by order of the Pope. But more authentic notices shew Banks as surviving in King Charles's time, in the capacity of a jolly vintner in Cheapside. It may at the same time be remarked that there would have been nothing decidedly extraordinary in the horse being committed with its master to a fiery purgation. 'In a little book entitled Le Diable Bossu, Nancy, 1708, 18mo, there is an obscure allusion to an English horse whose master had taught him to know the cards, and which was burned alive at Lisbon in 1707; and Mr. Granger, in his Biographical History of England (vol. iii., p. 164, edit. 1779), has informed us that, within his remembrance, a horse which had been taught to perform several tricks was, with his owner, put into the Inquisition.' -Douce's Illustrations of Shakespeare, i. 214. THE BATTLE OF PLASSEYThe 5th of February 1757 is noted as the date of the battle which may be said to have decided that the English should be the masters of India. Surajah Dowlah, the youthful Viceroy or Nabob of Bengal, had overpowered the British factory at Calcutta, and committed the monstrous cruelty of shutting up a hundred and forty-six English in the famous Black Hole, where, before morning, all but twenty-three had perished miserably. Against him came from Madras the 'heaven-born soldier' Robert Clive, with about three thousand troops, of which only a third were English, together with a fleet under Admiral Watson. Aided by a conspiracy in the Nabob's camp in favour of Meer Jaffier, and using many artifices and tricks which seemed to him justified by the practices of the enemy, Clive at length found himself at Cossimbuzar, a few miles from Plassey, where lay Surajah Dowlah with sixty thousand men. He had to consider that, if he crossed the intermediate river and failed in his attack, himself and his troops would be utterly lost. A council of war advised him against advancing. Yet, inspired by his wonderful genius, he determined on the bolder course. The Bengalese army advanced upon him with an appearance of power which would have appalled most men; but the first cannonade from the English threw it into confusion. It fled; Surajah descended into obscurity; and the English found India open to them. One hardly knows whether to be most astonished at the courage of Clive, or at the perfidious arts (extending in one instance to deliberate forgery) to which he at the same time descended in order to out-manoeuvre a too powerful enemy. The conduct of the English general is defended by his biographer Sir John Malcolm, but condemned by Lord Macaulay, who remarks that 'the maxim Honesty is the best policy' is even more true of states than of individuals, in as far as states are longer-lived, and adds, 'It is possible to mention men who have owed great worldly prosperity to breaches of private faith; but we doubt whether it is possible to mention a state which has on the whole been a gainer by a breach of public faith.' Insignificant as was the English force employed on this occasion, we must consider the encounter as, from its consequences, one of the great battles of the world. |