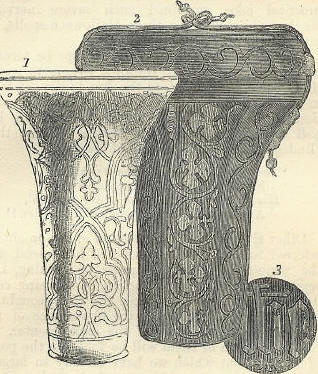

31st OctoberBorn: John Evelyn, author of Sylva, Memoirs, &c., 1620, Wotton, Surrey; Pope Clement XIV, 1705; Christopher Anstey, author of The New Bath Guide, 1724. Died: John Palaeologus, Greek emperor, 1448; John Bradshaw, presiding judge at trial of Charles I, 1659; Victor Amadeus, first king of Sardinia, 1732; William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, 1765; Jacques Pierre Brissot, distinguished Girondist, guillotined, 1793. Feast Day: St Quintin, martyr, 287. St. Foillan, martyr, 655. St. Wolfgang, bishop of Ratisbon, 994. HalloweenThere is perhaps no night in the year which the popular imagination has stamped with a more peculiar character than the evening of the 31st of October, known as All Hallow's Eve, or Halloween. It is clearly a relic of pagan times, for there is nothing in the church observance of the ensuing day of All Saints to have originated such extra ordinary notions as are connected with this celebrated festival, or such remarkable practices as those by which it is distinguished. The leading idea respecting Halloween is that it is the time, of all others, when supernatural influences prevail. It is the night set apart for a universal walking abroad of spirits, both of the visible and invisible world; for, as will be afterwards seen, one of the special characteristics attributed to this mystic evening, is the faculty conferred on the immaterial principle in humanity to detach itself from its corporeal tenement anal wander abroad through the realms of space. Divination is then believed to attain its highest power, and the gift asserted by Glendower of calling spirits 'from the vasty deep,' becomes available to all who choose to avail themselves of the privileges of the occasion. There is a remarkable uniformity in the fireside customs of this night all over the United Kingdom. Nuts and apples are everywhere in requisition, and consumed in immense numbers. Indeed the name of Nutcrack Night, by which Halloween is known in the north of England, indicates the predominance of the former of these articles in making up the entertainments of the evening. They are not only cracked and eaten, but made the means of vaticination in love affairs. And here we quote from Burns's poem of Halloween: The auld guidwife's well hoordit nits Are round and round divided, And mony lads' and lasses' fates Are there that night decided: Some kindle, couthie, side by side, And burn thegither trimly; Some start awa wi' saucy pride, And jump out owre the chimly Fu' high that night. Jean slips in twa wi' tentie e'e; Wha 'twas, she wadna tell; But this is Jock, and this is me, She says in to hersel': He bleezed owre her, and she owre him, As they wad never mair part; Till, fuff! he started up the lum, And Jean had e'en a sair heart To see 't that night. Brand, in his Popular Antiquities, is more explicit: It is a custom in Ireland, when the young women would. know if their lovers are faithful, to put three nuts upon the bars of the grate, naming the nuts after the lovers. If a nut cracks or jumps, the lover will prove unfaithful; if it begins to blaze or burn, he has a regard for the person making the trial. If the nuts named after the girl and her lover burn together, they will be married. As to apples, there is an old custom, perhaps still observed in some localities on this merry night, of hanging up a stick horizontally by a string from the ceiling, and putting a candle on the one end, and an apple on the other. The stick being made to twirl rapidly, the merry makers in succession leap up and snatch at the apple with their teeth (no use of the hands being allowed), but it very frequently happens that the candle comes round before they are aware, and scorches them in the face, or anoints them with grease. The disappointments and misadventures occasion, of course, abundance of laughter. But the grand sport with apples on Halloween, is to set them afloat in a tub of water, into which the juveniles, by turns, duck their heads with the view of catching an apple. Great fun goes on in watching the attempts of the youngster in the pursuit of the swimming fruit, which wriggles from side to side of the tub, and evades all attempts to capture it; whilst the disappointed aspirant is obliged to abandon the chase in favour of another whose turn has now arrived. The apples provided with stalks are generally caught first, and then comes the tug of war to win those which possess no such append-ages. Some competitors will deftly suck up the apple, if a small one, into their mouths. Others plunge manfully overhead in pursuit of a particular apple, and having forced it to the bottom of the tub, seize it firmly with their teeth, and emerge, dripping and triumphant, with their prize. This venturous procedure is generally rewarded with a hurrah! by the lookers on, and is recommended, by those versed in Halloween aquatics, as the only sure method of attaining success. In recent years, a practice has been introduced, probably by some tender mammas, timorous on the subject of their offspring catching cold, of dropping a fork from a height into the tub among the apples, and thus turning the sport into a display of marksmanship. It forms, however, but a very indifferent substitute for the joyous merriment of ducking and diving.  It is somewhat remarkable, that the sport of ducking for apples is not mentioned by Burns, whose celebrated poem of Halloween presents so graphic a picture of the ceremonies practised on that evening in the west of Scotland, in the poet's day. Many of the rites there described are now obsolete or nearly so, but two or three still retain place in various parts of the country. Among these is the custom still prevalent in Scotland, as the initiatory Halloween ceremony, of pulling kailstocks or stalks of colewort. The young people go out hand in hand, blindfolded, into the kailyard or garden, and each pulls the first stalk which he meets with. They then return to the fireside to inspect their prizes. According as the stalk is big or little, straight or crooked, so shall the future wife or husband be of the party by whom it is pulled. The quantity of earth sticking to the root denotes the amount of fortune or dowry; and the taste of the pith or custoc indicates the temper. Finally, the stalks are placed, one after another, over the door, and the Christian names of the persons who chance thereafter to enter the house are held in the same succession to indicate those of the individuals whom the parties are to marry. Another ceremony much practised on Halloween, is that of the Three Dishes or Luggies. Two of these are respectively filled with clean and foul water, and one is empty. They are ranged on the hearth, when the parties, blindfolded, advance in succession, and dip their fingers into one. If they dip into the clean water, they are to marry a maiden; if into the foul water, a widow; if into the empty dish, the party so dipping is destined to be either a bachelor or an old maid. As each person takes his turn, the position of the dishes is changed. Burns thus describes the custom: In order, on the clean hearth stane, The luggies three are ranged, And every time great care is ta'en To see them duly changed: Auld uncle John, wha wedlock's joys Sin' Mar's year did desire, Because he gat the toom dish thrice, He heaved them on the fire In wrath that night. The ceremonies above described are all of a light sportive description, but there are others of a more weird like and fearful character, which in this enlightened incredulous age have fallen very much into desuetude. One of these is the celebrated spell of eating an apple before a looking glass, with the view of discovering the inquirer's future husband, who it is believed will be seen peeping over her shoulder. A curious, and withal, cautious, little maiden, who desires to try this spell, is thus represented by Burns: Wee Jenny to her granny says: 'Will ye go wi' me, granny? I'll eat the apple at the glass, I gat frae uncle Johnny. A request which rouses the indignation of the old lady: She fuff't her pipe wi' sic a lunt, In wrath she was sae vap'rin', She notic't na, an aizle brunt Her braw new worset apron Out through that night. 'Ye little skelpie limmer's face! I daur you try sic sportin', As seek the foul thief ony place, For him to spae your fortune: Nae doubt but ye may get a sight! Great cause ye hae to fear it; For mony a ane has gotten a fright, And lived and died deleeret, On sic a night. Granny's warning was by no means a needless one, as several well authenticated instances are related of persons who, either from the effects of their own imagination, or some thoughtless practical joke, sustained such severe nervous shocks, while essaying these Halloween spells, as seriously to imperil their health. Another of these, what may perhaps be termed unhallowed, rites of All Hallows' Eve, is to wet a shirt sleeve, hang it up to the fire to dry, and lie in bed watching it till midnight, when the apparition of the individual's future partner for life will come in and turn the sleeve. Bums thus alludes to the practice in one of his songs: The last Halloween I was waukin', My droukit sark sleeve, as ye ken; His likeness cam' up the house staukin', And the very gray breeks o' Tam Glen! Other rites for the invocation of spirits might be referred to, such as the sowing of hemp seed, and the winnowing of three wechts of nothing, i. e., repeating three times the action of exposing corn to the wind. In all of these the effect sought to be produced is the same the appearance of the future husband or wife of the experimenter. A full description of them will be found in the poem of Burns, from which we have already so largely quoted. It may here be remarked, that popular belief ascribes to children born on Halloween, the possession of certain mysterious faculties, such as that of perceiving and holding converse with supernatural beings. Sir Walter Scott, it will be recollected, makes use of this circumstance in his romance of The Monastery. In conclusion, we shall introduce an interesting story, with which we have been favoured by a lady. The leading incidents of the narrative may be relied on as correct, and the whole affair forms matter of curious thought on the subject of Halloween divination: Mr. and Mrs. M were a happy young couple, who, in the middle of the last century, resided on their own estate in a pleasant part of the province of Leinster, in Ireland. Enjoying a handsome competence, they spent their time in various rural occupations; and the birth of a little girl promised to crown their felicity, and provide them with an object of perpetual interest. On the Halloween following this last event, the parents retired to rest at their usual hour, Mrs. M having her infant on her arm, so that she might be roused by the slightest uneasiness it might exhibit. From teething or some other ailment, the child, about midnight, became very restless, and not receiving the accustomed attention from its mother, cried so violently as to waken Mr. M. He at once called his wife, and told her the baby was uneasy, but received no answer. He called again more loudly, but still to no purpose; she seemed to be in a heavy uneasy slumber, and when all her husband's attempts to rouse her by calling and shaking proved ineffectual, he was obliged to take the child himself, and try to appease its wailings. After many vain attempts of this sort on his part, the little creature at last sobbed itself to rest, and the mother slept on till a much later hour than her usual time of rising in the morning. When Mr. M saw that she was awake, he told her of the restlessness of the baby during the night, and how, after having tried in vain every means to rouse her, he had at last been obliged to make an awkward attempt to take her place, and lost thereby some hours of his night's rest. 'I, too,' she replied, 'have passed the most miserable night that I ever experienced; I now see that sleep and rest are two different things, for I never felt so unrefreshed in my life. How I wish you had been able to awake me it would have spared me some of my fatigue and anxiety! I thought I was dragged against my will into a strange part of the country, where I had never been before, and, after what appeared to me a long and weary journey on foot, I arrived at a comfortable looking house. I went in longing to rest, but had no power to sit down, although there was a nice supper laid out before a good fire, and every appearance of preparations for an expected visitor. Exhausted as I felt, I was only allowed to stand for a minute or two, and then hurried away by the same road back again; but now it is over, and after all it was only a dream.' Her husband listened with interest to her story, and then sighing deeply, said: 'My dear Sarah, you will not long have me beside you; whoever is to be your second husband played last night some evil trick of which you have been the victim.' Shocked as she felt at this announcement, she endeavoured to suppress her own feelings and rally her husband's spirits, hoping that it would pass from his mind as soon as he had become engrossed by the active business of the day. Some months passed tranquilly away after this occurrence, and the dream on Halloween night had well nigh been forgotten by both husband and wife, when Mr. M's health began to fail. He had never been a robust man, and he now declined so rapidly, that in a short time, notwithstanding all the remedies and attentions that skill could suggest, or affection bestow, his wife was left a mourning widow. Her energetic mind and active habits, however, prevented her from abandoning herself to the desolation of grief. She continued, as her husband had done during his life, to farm the estate, and in this employment, and the education of her little girl, she found ample and salutary occupation. Alike admired and beloved for the judicious management of her worldly affairs, and her true Christian benevolence and kindliness of heart, she might easily, had she been so inclined, have established herself respectably for a second time in life, but such a thought seemed never to cross her mind. She had an uncle, a wise, kind old man, who, living at a distance, often paid a visit to the widow, looked over her farm, and gave her useful advice and assistance. This old gentleman had a neighbour named C, a prudent young man, who stood very high in his favour. Whenever they met, Mrs. M's uncle was in the habit of rallying him on the subject of matrimony. On one occasion of this kind, C excused himself by saying that it really was not his fault that he was still a bachelor, as he was anxious to settle in life, but had never met with any woman whom he should like to call his wife. 'Well, C,' replied his old friend, 'you are, I am afraid, a saucy fellow, but if you put yourself into my hands, I do not despair of suiting you.' Some bantering then ensued, and the colloquy terminated by Mrs. M's uncle inviting the young man to ride over with him next day and visit his niece, whom C had never yet seen. The proffer was readily accepted; the two friends started early on the following morning, and after a pleasant ride, were approaching their destination. Here they descried, at a little distance, Mrs. M retreating towards her house, after making her usual matutinal inspection of her farm. The first glance which Mr. C obtained of her made him start violently, and the more he looked his agitation increased. Then laying his hand on the arm of his friend, and pointing his finger in the direction of Mrs. M, he said: 'Mr., we need not go any further, for if ever I am to be married, there is my wife!' Well, C, was the reply,that is my niece, to whom I am about to introduce you; but tell me, he added,is this what you call love at first sight, or what do you mean by your sudden decision in favour of a person with whom you have never exchanged a word? Why, sir, replied the young man, I find I have betrayed myself, and must now make my confession. A year or two ago, I tried a Halloween spell, and sat up all night to watch the result. I declare to you most solemnly, that the figure of that lady, as I now see her, entered my room and looked at me. She stood a minute or two by the fire and then disappeared as suddenly as she came. I was wide awake, and felt considerable remorse at having thus ventured to tamper with the powers of the unseen world; but I assure you, that every particular of her features, dress, and figure, have been so present to my mind ever since, that I could not possibly make a mistake, and the moment I saw your niece, I was convinced that she was indeed the woman whose image I beheld on that never to be forgotten Halloween. The old gentleman, as may be anticipated, was not a little astonished at his friend's statement, but all comments on it were for the time put a stop to by their arrival at Mrs. M's house. She was glad to see her uncle, and made his friend welcome, performing the duties of hospitality with a simplicity and heartiness that were very attractive to her stranger guest. After her visitors had refreshed themselves, her uncle walked out with her to look over the farm, and took opportunity, in the absence of Mr. C, to recommend him to the favourable consideration of his niece. To make a long story short, the impression was mutually agreeable. Mr. C, before leaving the house, obtained permission from Mrs. M to visit her, and after a brief courtship, they were married. They lived long and happily together, and it was from their daughter that our informant derived that remarkable episode in the history of her parents which we have above narrated. THE LUCK OF EDENHALL At Edenhall, the seat of the ancient family of Musgrave, near Penrith, in Cumberland, the curious drinking cup, figured below, is preserved as one of the most cherished heirlooms. It is composed of very thin glass, ornamented on the outside with a variety of coloured devices, and will hold about an English pint. The legend regarding it is, that the butler of the family having gone one night to draw water at the well of St. Cuthbert, a copious spring in the garden of the mansion of Edenhall, surprised a group of fairies disporting themselves beside the well, at the margin of which stood the drinking-glass under notice. He seized hold of it, and a struggle for its recovery ensued between him and the fairies. The elves were worsted, and, there-upon took to flight, exclaiming: If this glass do break or fall Farewell the luck of Edenhall! The extreme thinness of the glass rendering it very liable to breakage, was probably the origin of the legend, which has been related of this goblet from time immemorial. Its real history cannot now be ascertained, but from the letters I.H.S. inscribed on the top of the case containing it, it has been surmised to have been originally used as a chalice. In the drawing, fig. 1 represents the glass, fig. 2 its leathern case, and fig. 3 the inscription on the top of the latter. The wild and hair brained Duke of Wharton is said, on one occasion, to have nearly destroyed the Luck of Edenhall, by letting it drop from his hands; but the precious vessel was saved by the presence of mind of the butler, who caught it in a napkin. The same nobleman enjoys the credit of having composed a burlesque poem in reference to it, written as a parody on Chevy Chase, and which commences thus: God prosper long from being broke The Luck of Edenhall! The real author, however, was Lloyd, a boon companion of the duke. Uhland, the German poet, has also a ballad, Des Glück von Edenhall, based on this celebrated legend. VISIT OF MARIE DE MEDICI TO ENGLANDOn the 31st of October 1638, Marie de Medici arrived in the city of London, on a visit to the English court. Though she was received with all the honours due to the queen dowager of France, and the mother of Henrietta, queen of England, yet both court and people considered the visit ill timed, and the guest unwelcome. Bishop Laud, in his private diary, noticing her arrival, says that he has 'great apprehensions on this business. For indeed,' he continues, 'the English people hate or suspect her, for the sake of her church, her country, and her daughter; and having shifted her residence in other countries, upon calamities and troubles which still pursue her, they think it her fate to carry misfortunes with her, and so dread her as an ill boding meteor.' Daughter of the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Marie de Medici, for mere reasons of state, was married to Henry IV, king of France. Henry gained by her the heir he desired, but her unsociable, haughty, and intractable disposition, rendered his life miserable, and it is still considered a doubtful question, whether she were not privy to the plot which caused his death by assassination in 1610. On this event taking place, she attained the height of her power, in acquiring the regency of France; but fully as feeble-minded as she was ambitious, she suffered herself to be ruled by the most unworthy favourites, and the inevitable results quickly followed. She secured, however, for her service, one person of conduct and abilities, who cannot be passed over without notice. Attracted by the eloquent sermons of a young Parisian ecclesiastic, named Armand de Plessis, Marie appointed him to be her almoner, and afterwards made him principal secretary of state; but this man, better known by his later title of Cardinal Richelieu, was fated to become her evil genius and bitterest enemy. During the seven years in which the regency of Marie de Medici lasted, France was convulsed with broils, cabals, and intrigues. At length her son, Louis XIII, assuming the government, caused his mother's unworthy favourite, the Marshal d'Ancre, to be murdered, and his wife to be tried and executed for the alleged crime of sorcery; the wretched woman to the last asserting, that the influence of a strong mind over a weak one was the only witchcraft she had used. Marie would have contended against her son in open war, but Richelieu joining the king, and threatening to imprison her for life, she was forced, in 1631, to take refuge at Brussels, where she lived for seven years, supported by a pension from the Spanish court, her daughter Elizabeth being wife of Philip IV of Spain. Restlessly intriguing, but ever foiled by the superior diplomacy of Richelieu, she fled from Brussels to Holland, greatly to the indignation of Philip, who at once stopped her allowance, refusing even to pay the arrears then due to her. It seems as if the fates had combined to punish this miserable old woman, for, besides the popular commotions excited by her intrigues, disasters not attributable to her presence namely, pestilence, famine, and war ever dogged her foot steps. Richelieu would have allowed her a liberal annuity, if she would only return to Italy; but this her pride would not permit her to do; moreover, it would be giving up the field to an enemy and rival, whom she still hoped to overcome. So she begged her son-in-law, Charles I, to receive her in England, a request he, with his usual imprudence, generously granted; for he had been forced, by repeated remonstrances of parliament, a few years previous, to dismiss his own queen's foreign chaplains and servants; and it was not likely that her mother, who brought over a new train, should escape unnoticed. There were, indeed, strong reasons for Laud's forebodings and the people's fears. She had a grand reception, however. Waller, the court poet, dedicated a poem to her, commencing thus: Great Queen of Europe! where thy offspring wears All the chief crowns; where princes are thy heirs As welcome thou to sea girt Britain's shore, As erst Latona, who fair Cynthia bore, To Delos was. St. James's Palace was given to her as a residence, where she kept a petty court of her own, Charles, it is said, allowing her the large sum of £40,000 per annum. But evil days were at hand. The populace ever regarded her as an enemy, and in the excitement caused by Strafford's trial, she was mobbed and insulted, even in the palace of St. James's. She applied to the king for protection, but he, being then nearly powerless, could do no more than refer her to parliament. The Commons allowed her a temporary guard of one hundred men, petitioning the king to send her out of the country; and not ungenerously offering, if she went at once, to vote her £10,000, with an intimation that they might send more to her, if she were well out of England The question was, where could she go? seeing that no country would receive her. At last having secured a refuge in the free city of Cologne, she left England in August 1641, the Earl of Arundel, at the king's request, accompanying her, Lilly, with a feeling one would scarcely have expected, thus notices her departure. I beheld the old queen mother of France departing from London. A sad spectacle it was, and produced tears from may eyes, and many other beholders, to see an aged, lean, decrepit, poor queen, ready for her grave, necessitated to depart hence, having no place of residence left her, but where the courtesy of her hard fate assigned. She had been the only stately magnificent woman of Europe, wife to the greatest king that ever lived in France, mother unto one king and two queens. The misfortunes of this woman attended her to the last. Her friends, under the circumstances, thought it most advisable to invest the £10,000 given her by parliament in an English estate, and as the civil war broke out immediately after, she never received the slightest benefit from it. She died the year following at Cologne, in a garret, destitute of the common necessaries of life. Chigi, the pope's legate, attended her when dying, and induced her to express forgiveness of Richelieu's ingratitude. But when further pressed to send the cardinal, as a token of complete forgiveness, a valued bracelet, that never was allowed to leave her arm, she muttered: 'It is too much!' turned her face to the wall, and expired. The illustration representing Marie's public entrance into London is considered peculiarly interesting; the engraving from which it is taken being one of the only two street views extant of the city previous to the great fire. The scene depicted is about the middle of Cheapside; the cross, which stood near the end of Wood Street, forming a conspicuous feature. This was one of the crosses erected by Edward I, in memory of his beloved queen, Eleanor of Castile. It had been frequently repaired and furbished up for various public occasions. Towards the end of Elizabeth's reign, it received some injuries from the ultra Protestant party; but these were repaired, the iron railing put round the base (as seen in the engraving) and the upper part gilded, in honour of James I's first visit to the city. Those were the last repairs it ever received. After sustaining several petty injuries from the Puritans, the House of Commons decreed that it should be destroyed; and in May 1643, the order was carried into effect amid the shouts of the populace. The building to the right, eastward of the Cross, represents the Standard, which, with a conduit attached, stood nearly opposite the end of Milk Street. Stow describes it exactly as represented in the engraving a square pillar, faced with statues, the upper part surrounded by a balcony, and the top crowned with an angel or a figure of Fame, blowing a trumpet. The numerous signs seen in the illustration, exhibit a curious feature of old London. The sign on the right is still a not uncommon one, ' the Nag's Head,' and the bush or garland suspended by it, shew that it was the sign of a tavern. When every house had a sign, and the shop windows were too small to afford any index of the trade carried on within, publicans found it convenient to exhibit the bush. But when a tavern was well established, and had acquired a name for the quality of its liquors, the garland might be laid aside; for, as the old proverb said, 'Good wine needs no bush.' |