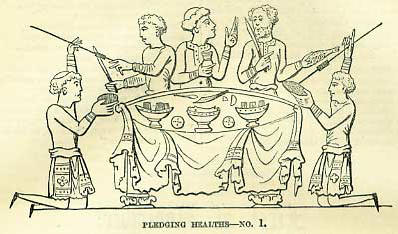

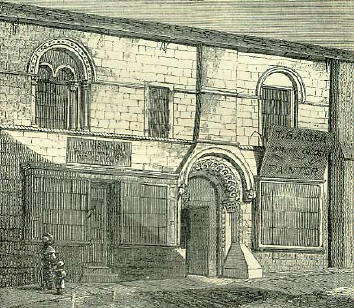

1st NovemberBorn: Benvenuto Cellini, celebrated silversmith and sculptor in metal, 1500, Florence; Denzil Hollis, reforming patriot, 1597, Haughton, Northamptonshire; Sir Matthew Hale, eminent judge, 1609, Alderley, Gloucestershire; Nicolas Boileau, poetical satirist, 1636, France; Bishop George Horne, biblical expositor, 1730, Otham, near Maidstone; Lydia Huntley Sigourney, American poet, 1791, Norwich, United States. Died: Charles II of Spain, 1700; Dr. John Radcliffe, founder of the Radcliffe Library, Oxford, 1714; Dean Humphrey Prideaux, author of Connection of the History of the Old and New Testament, 1724, Norwich; Louisa de Kerouaille, Duchess of Portsmouth, mistress of Charles II., 1734; Alexander Cruden, author of the Concordance, 1770, Islington; Edward Shuter, comedian, 1776; Lord George Gordon, originator of the No-Popery Riots of 1780, 1793, Newgate, London. Feast Day: The Festival of All-Saints. St. Beniguus, apostle of Burgundy, martyr, 3rd century. St. Austremonius, 3rd century. St. Caesarius, martyr, 300. St. Mary, martyr, 4th century. St. Marcellus, bishop of Paris, confessor, beginning of 5th century. St. Harold, king of Denmark, martyr, 980. ALL SAINTS DAYThis festival takes its origin from the conversion, in the seventh century, of the Pantheon at Rome into a Christian place of worship, and its dedication by Pope Boniface IV to the Virgin and all the martyrs. The anniversary of this event was at first celebrated on the 1st of May, but the day was subsequently altered to the 1st of November, which was thenceforth, under the designation of the Feast of All Saints, set apart as a general commemoration in their honour. The festival has been retained by the Anglican Church. SIR MATTHEW HALE: DRINKING OF HEALTHSThe illustrious chief-justice left an injunction or advice for his grandchildren in the following terms: I will not have you begin or pledge any health, for it is become one of the greatest artifices of drinking, and occasions of quarrelling in the kingdom. If you pledge one health, you oblige yourself to pledge another, and a third, and so onwards; and if you pledge as many as will be drank, you must be debauched and drunk. If they will needs know the reason of your refusal, it is a fair answer: ' That your grandfather that brought you up, from whom, under God, you have the estate you enjoy or expect, left this in command with you, that you should never begin or pledge a health. Sir Matthew might well condemn health-drinking, for in his days it was used, or rather abused, for the encouragement of excesses at which all virtuous people must have been appalled. The custom has, however, a foundation and a sanction in the social feelings, and consequently, though it has had many ups and downs, it has always hitherto, in one form or another, maintained its ground. As far back as we can go amongst our ancestors, we find it established. And, notwithstanding the frowns of refinement on the one hand, and tee-totalism on the other, we undoubtedly see it occasionally practised. Among the earliest instances of the custom may be cited the somewhat familiar one of the health, said to have been drunk by Rowena to Vortigern, and which is described by Verstegan after this fashion: She came into the room where the king and his guests were sitting, and making a low obedience to him, she said: ' [Vaes heal, hlaford Cyning' (Be of health, Lord King). Then, having drunk, she presented it [the cup] on her knees to the king, who, being told the meaning of what she said, together with the custom, took the cup, saying: 'Drink heal' [Drink health], and drank also. William of Malmesbury adverts to the custom thus: It is said it first took its rise from the death of young King Edward (called the Martyr), son to Edgar, who was, by the contrivance of Elfrida, his step-mother, traitorously stabbed in the back as he was drinking. The following curious old delineation, from the Cotton Manuscript, seems to agree with the reported custom. The centre figure appears to be addressing himself to his companion, who tells him that he pledges him, holding up his knife in token of his readiness to assist and protect him:  In another illustration of the same period, the custom of individuals pledging each other on convivial occasions is more prominently represented:  The following account of a curious custom in connection with the drinking of healths, is from a contribution to Notes and Queries, by a Lichfield correspondent, who says, that in that ancient city, it has been observed from time immemorial, at dinners given by the mayor, or at any public feast of the corporation. The first two toasts given are 'The Queen,' and 'Weale and worship,' both which are drunk out of a massive embossed silver cup, holding three or four quarts, presented to the corporation in 1666, by the celebrated Elias Ash-mole, a native of the city. The ceremony itself is by the same writer thus more particularly described: The mayor drinks first, and on his rising, the persons on his right and left also rise. He then hands the cup to the person on his right side, when the one next to him rises, the one on the left of the mayor still standing. Then the cup is passed across the table to him, when his left-hand neighbour rises; so that there are always three standing at the same time-one next to the person who drinks, and one opposite to him. From the curious old letter of thanks for this cup we quote the following lines: Now, sir, give us leave to conclude by informing you that, according to your desire (upon the first receipt of your Poculum Charitatis, at the sign of the George for England), we filled it with Catholic wine, and devoted it a sober health to our most gracious king, which (being of so large a continent) pass the hands of thirty to pledge; nor did we forget yourself in the next place, being our great Meccenas. This letter of thanks is dated, 'Litchfield, 26th January 1666.' The whole of the original letter appears in Harwood's Lichfield. The custom as practised in the passing of the renowned 'loving-cup,' at the lord mayor's feasts in London, is too well known to require further notice. Another writer in Notes and Queries says, that the same observance always had place at the parish meetings, and church wardens' dinners, at St. Margaret's, Westminster: the cover of the loving-cup being held over the head of the person drinking by his neighbours on his right and left hand.' It appears from Barrington's Observations on the Ancient Statutes (1766), that the custom prevailed at Queen's College, Oxford, where the scholars who wait upon their fellows place their two thumbs on the table. The writer adds: I have heard that the same ceremony is used in some parts of Germany, whilst the superior drinks the health of the inferior. The inferior, during this, places his two thumbs on the table, and therefore is incapacitated from making any attempt upon the life of the person who is drinking. The writer on the Lichfield custom also adverts to this, by the by, when he says that, 'he presumes that though the ceremony is different, the object is the same as that at Queen's College-viz, to prevent injury to the person who drinks.' The practice would appear to have had its origin at the time when the Danes bore sway in this country. Indeed, some authors deduce the expression, 'I'll pledge you,' in drinking, from this period. It seems that the Northmen, in those days, would occasionally stab a person while in the act of drinking. In consequence, people would not drink in company, unless some one present would be their pledge, or surety, that they should come to no harm whilst thus engaged. Nay, at one time, the people became so intimidated that they would not dare to drink until the Danes had actually pledged their honour for their safety! In Beaumont and Fletcher's days, it was the custom for the young gallants to stab themselves in their arms, or elsewhere, in order to 'drink the healthy' of their mistresses, or to write their names in their own blood! The following passage occurs in Pepys's Diary relative to 'health-drinking:' To the Rhenish wine-house, where Mr. Moore shewed us the French manner, when a health is drunk, to bow to him that drunk to you, and then apply yourself to him, whose lady's health is drunk, and then to the person that you drink to, which I never knew before: but it seems it is now the fashion. The following remarkable and solemn passage is found in Ward's Living Speeches of Dying Christians (in his Sermons): My Saviour began to mee in a bitter cup; and shall I not pledge him? i. e., drink the same. Records of the custom in many countries, and in many ages, might be multiplied ad infinitum. It is beyond our present purpose, however, to give any further illustrations, beyond the following curious extract from Rich's Irish Hvbbvb, or the English Hve and Crie (1617). After a long and wholesome, though severe, tirade against drunkenness, the quaint old writer says: 'In former ages, they had no conceits whereby to draw on drinkennes; their best was, I drinke to you, and I pledge Lund; till at length some shallow-witted drunkard found out the carouse, which shortly after was turned into a hearty draught: but now it is ingined [enjoined] to the drinking of a health, an invention of that worth and worthinesse, as it ispitty the first founder was not hanged, that wee might haue found out his name in the ancient record of the Hangman's Register! The institution in drinking of a health is full of ceremonie, and obserued by tradition, as the papists doe their praying to saints.' The singular writer then adds this description of the performance of the custom: 'He that begins the health, hath his prescribed orders; first uncovering his head, he takes a full cup in his hand, and setling his countenance with a graue aspect, he craues for audience. Silence being once obtained, hee begins to breath out the name, peraduenture of some honorable personage that is worthy of a better regard than to have his name pollvted at so vnfitting a time, amongst a company of drunkards; but his health is drunke to, and hee that pledgeth must likewise of [off] with his cap, kisse his fingers, and bowing himselfe in signe of a reuerent acceptance. When the leader sees his follower thus prepared, he soupes [sups] up his broath, turnes the bottom of the cuppe vpward, and in ostentation of his dexteritie, glues the cup a phylip [fillip], to make it cry tynge [a sort of ringing sound, denoting that the vessel was emptied of its contents]. And thus the first scene is acted.-The cup being newly replenished to the breadth of a haire, he that is the pledger must now begin his part, and thus it goes round throughout the whole company, prouided alwaies by a canon set downe by the first founder, there must be three at the least still vncouered, till the health hath had the full passage; which is no sooner ended, but another begins againe, and he drinkes a health to his Lady of little worth, or, peraduenture, to his Light-heel'd mistris. The caustic old writer just referred to, adds the following remarks in a marginal note: He that first invented that use of drinking healths, had his braines beat out with a pottle-pot: a most lust end for inventers of such notorious abuses. And many in pledging of healths haue ended their lines presently [early], as example lately in London. A few notices may be appended of the anathemas which have been hurled at the custom of drinking healths. The first of these is a singular tract published in 1628, 'by William Prynne, Gent., proving the drinking and pledging of Healths to be sinful, and utterly unlawful unto Christians.' At the Restoration, this work had become scarce, and 'it was judged meet that Mr. William Prynne's notable book should be reprinted, few of them being to be had for money.' The loyalty of the English to Charles IL, was shewn by such. a frequency of drinking his health, as to threaten to disturb the public peace, and occasion a royal proclamation, an extract from which is subjoined. C. R. Our dislike of those, who under pretence of affection to us, and our service, assums to themselves a Liberty of Reviling, Threatning, and Reproaching of others. There are likewise another sort of men, of whom we have heard much, and are sufficiently ashamed, who spend their time in Taverns, Tipling-houses, and Debauches, giving no other evidence of their affection to us, but in Drinking Our HEALTH.' The following is from a work published about this period: Of Healths drinking, and Heaven's doom thereon: Part of a Letter from Mr. Ab. Ramsbotham. Within four or five miles of my house, the first of July (as I take it), at a town called Geslingham, there were three or four persons in a shopkeeper's house, drinking of Strong waters, and of HEALTHS, as 'tis spoken. And all of a sudden there came a flame of fire down the chimney with a great crack, as of thunder, or of a canon, or granado; which for the present struck the men as dead. But afterwards they recovered; and one of them was, as it were, shot in the knee, and so up his Breeches and Doublet to his shoulder; and there it brake out, and split and brake in pieces the window, and set the house on fire; the greater part of which burned down to the ground. This hath filled the Country with wonder, and many speak their judgements both on it, and of the persons. ABR. RAMSBOTHAM. DR. RADCLIFFEJohn Radcliffe, whose name is perpetuated in so many memorials of his munificence, was born at Wakefield, in Yorkshire, February 7, 1650, and educated in the university of Oxford, where he studied medicine. His books were so few in number, that on being asked where was his library, he pointed to a few vials, a skeleton, and a herbal, in one corner of his room, and exclaimed, with emphasis: 'There, sir, is Radcliffe's library!' In 1675, he took his degree of M.B., and began to practise in Oxford, where, by some happy cures (especially by his cooling treatment of the small-pox), he soon acquired a great reputation. In 1682, he took the degree of M.D., and went out a Grand Compounder; an imposing ceremony in those days, and for a century afterwards, all the members of the college walking in procession, with the candidate himself, bareheaded, to the Convocation House. Radcliffe now removed to London, and settled in Bow Street, Covent Garden, where he soon received daily, in fees, the sum of twenty guineas, through his vigorous and decisive method of practice, as well as his pleasantry and ready wit -many, it is said, even feigning themselves ill, for the pleasure of having a few minutes' conversation with the facetious doctor. The garden in the rear of his house, in Bow Street, extended to the garden of Sir Godfrey Kneller, who resided in the Piazza, Covent Garden. Kneller was fond of flowers, and had a fine collection. As he was intimate with the physician, he permitted the latter to have a door into his garden; but Radcliffe's servants gathering and destroying the flowers, Kneller sent him notice that he must shut up the door. Radcliffe replied peevishly: 'Tell him he may do anything with it but paint it' 'And I,' answered Sir Godfrey, 'can take anything from him but physic.' Radcliffe sheaved great sagacity in resisting the entreaties of the court-chaplains to change his religion and turn papist; and when the Prince of Orange was invited over, Radcliffe took care that no imputation of guilt could, by any possibility, attach to him afterwards, had the Revolution not succeeded. He had, two years previously, been appointed physician to the Princess Anne; and when King William came, Radcliffe got the start of his majesty's physicians, by curing two of his favourite foreign attendants; for which the king gave him five hundred guineas out of the privy-purse. But Radcliffe declined the appointment of one of his majesty's physicians, considering that the settlement of the crown was then but insecure. He nevertheless attended the king, and for the first eleven years of his reign, received more than 600 guineas annually. In 1689, he succeeded in restoring William sufficiently to enable him to join his army in Ireland, and gain the victory of the Boyne. In 1691, when the young Prince William, Duke of Gloucester, was taken ill of fainting fits, and his life was despaired of, Radcliffe was sent for, and restored the little patient, for which Queen Mary ordered her chamberlain to present him with a thousand guineas. He was now the great physician of the day; and his neighbour, Dr. Gibbons, received £1000 per annum from the overflow of patients who were not able to get admission to Radcliffe. In 1692, he sustained a severe pecuniary loss. He was persuaded by his friend, Betterton, the famous tragedian, to risk £5000 in a venture to the East Indies; the ship was captured by the enemy, with her cargo, worth £120,000. This ruined the poor player; but Radcliffe received the disastrous intelligence at the Bull's Head Tavern, in Clare Market (where he was enjoying himself with several persons of rank), with philosophic composure; desiring his companions not to interrupt the circulation of the glass, for that 'he had no more to do but go up so many pair of stairs, to make himself whole again.' Towards the end of 1694, Queen Mary was seized with small-pox, and the symptoms were most alarming; her majesty's physicians were at their wits' end, and the privy-council sent for Radcliffe. At the first sight of the prescriptions, he rudely exclaimed, that ' her majesty was a dead woman, for it was impossible to do any good in her case, where remedies were given that were so contrary to the nature of the distemper; yet he would endeavour to do all that lay in him to give her ease.' There were some faint hopes for a time, but the queen died. Some few months after, Radcliffe's attendance was requested by the Princess Anne. He had been drinking freely, and promised speedily to come to St. James's; the princess grew worse, and a messenger was again despatched to Radcliffe, who, on hearing the symptoms detailed, swore by his Maker, 'that her highness' distemper was nothing but the vapours, and that she was in as good a state of health as any woman breathing, could she but believe it.' No skill or reputation could excuse this rudeness and levity; and he was, in consequence, dismissed. But his credit remained with the king, who sent him abroad to attend the Earl of Albemarle, who had a considerable command in the army; Radcliffe remained in the camp only a week, succeeded in the treatment of his patient, and received from King William £1200, and from Lord Albemarle 400 guineas and a diamond ring. In 1697, after the king's return from Loo, being much indisposed at Kensington Palace, he sent for Radcliffe; the symptoms were dropsical, when the physician, in his odd way, promised to try to lengthen the king's days, if he would forbear making long visits to the Earl of Bradford, with whom the king was wont to drink very hard. Radcliffe left behind him a recipe, by following which the king was enabled to go abroad, to his palace at Loo, in Holland. In 1699, the Duke of Gloucester, heir-presumptive to the crown, was taken ill, when his mother, the Princess Anne, notwithstanding her antipathy, sent for Radcliffe, who pronounced the case hopeless, and abused the two other physicians, telling them that 'it would have been happy for this nation had the first been bred up a basket-maker (which was his father's occupation), and the last continued making a havock of nouns and pronouns, in the quality of a country schoolmaster, rather than have ventured out of his reach, in the practice of an art which he was an utter stranger to, and for which he ought to have been whipped with one of his own rods.' At the close of this year, the king, on his return from Holland, where he had not been abstemious, being much out of health, again sent for Radcliffe to Kensington Palace; when his majesty, shewing his swollen ankles, exclaimed 'Doctor, what think you of these? 'Why, Why, truly,' said. Radcliffe, 'I would not have your majesty's two legs for your three kingdoms.' With this ill-timed jest, though it passed unnoticed at the moment, his professional attendance at court terminated. Anne sent again for Radcliffe in the dangerous illness of her husband, Prince George. His disease was dropsy, and the doctor, unused to flatter, declared that ' the prince had been so tampered with, that nothing in the art of physic could keep him alive more than six days '-and his prediction was verified. When, in July 1714, Queen Anne was seized with the sickness which terminated her life, Radcliffe was sent for; but he was confined by a fit of gout to his house at Carshalton. He was accused of refusing to give his professional advice to his sovereign, and in consequence of this report, durst scarcely venture out of doors, as he was threatened with being pulled to pieces if ever he came to London. Radcliffe died November 1, 1714, ' a victim to the ingratitude of a thankless world, and the fury of the gout.' By his will he left his Yorkshire estate to University College, Oxford, and £5000 for enlargement of the building; to St. Bartholomew's Hospital, the yearly sum of £500 towards mending their diet, and £100 yearly for the buying of linen; and £40,000 for the building of a library at Oxford, besides £150 a year for the librarian's salary, £100 a year for the purchase of books, and another £100 for repairs. The smallness of the annual sum provided for the purchase of books is remarkable, and gave occasion to the animadversion, that the main object of the testator was to erect a splendid monument to himself. The bulk of the remainder of his property he left in trust for charitable purposes. The Radcliffe Library is one of the noblest architectural adornments of Oxford. It was designed by Gibbs, and is built on a circular plan, with a spacious dome. It was originally called the Physic Library, and the books which it contains are principally confined to works on medicine and natural science. ALEXANDER CRUDENThis persevering and painstaking compiler, who was appointed by Sir Robert Walpole bookseller to the queen of George II, died at his lodgings in Camden Street, Islington, November 1, 1770. The Concordance, which has conferred celebrity on his name, was published and dedicated to Queen Caroline in 1737. He was permitted to present a copy of it in person to her majesty, who, he said, smiled upon him, and assured him she was highly obliged to him. The expectations he formed of receiving a solid proof of the queen's appreciation of the work, were disappointed by her sudden death within sixteen days of his reception. Twenty-four years afterwards, he revised a second edition, and dedicated it to her grandson, George III For this, and a third edition issued in 1769, his booksellers gave him £800. He was often prominently before the public as a very eccentric enthusiast. Three times, during his life, he was placed in confinement by his friends. On the second of these occasions, he managed to escape from a private lunatic asylum in which he was chained to his bedstead; when he immediately brought actions against the proprietor and physician. Unfortunately for his case, he stated it himself, and lost it. On his third release, he brought an action against his sister, from whom he claimed damages to the amount of £10,000, for authorising his detention. In this suit also he was unsuccessful. In the course of his life, he met with many rebuffs in the prosecution of projects in which he restlessly embarked, as he considered, for the public good; for all of which he solaced himself with printing accounts of his motives, treatment, and disappointments. One of his eccentricities consisted in the assumption of the title of Alexander the Corrector. In the capacity implied by this term, he stopped persons whom he met in public places on Sundays, and admonished them to go home and keep the Sabbath-day holy; and in many other ways addressed himself to the improvement of the public morals. He spent much of his earnings in the purchase of tracts and catechisms, which he distributed right and left; and gave away some thousands of hand-bills, on which were printed the fourth commandment. To enlarge, as he thought, his sphere of usefulness, he sighed for a recognition of his mission in high-places; and, to attain this end, succeeded, after considerable solicitation, in obtaining the signatures of several persons of rank to a testimonial of his zeal for the public good. Armed with this credential, he urged that the king in council, or an act of legislature, should formally constitute him Corrector of Morals. However, his chimerical application was not entertained. Another eccentricity arose out of the decided part he took against Mr. Wilkes, when that demagogue agitated the kingdom. He partly expressed his intense feeling in his usual mode-by pamphlet; but more especially evinced his aversion by effacing the offensive numeral No. 45, wherever he found it chalked up. For this purpose, he carried in his pockets a large piece of sponge. He subsequently included in this obliteration all the obscene inscriptions with which idle persons were permitted at that time to disgrace blank walls in the metropolis. This occupation, says his biographer Blackburn, from its retrospective character, made his walks very tedious. His erratic benevolence prompted him to visit the prisoners in Newgate daily, instruct them in the teachings of the gospel, and encourage them to pay attention, by gifts of money to the most diligent. This good work he was, however, induced to relinquish, by finding that his hardened pupils, directly he had turned his back, spent these sums in intoxicating liquors. While so engaged, he was able to prevail upon Lord Halifax to commute a sentence of death against Richard Potter, found guilty of uttering a forged will, to one of transportation. Still animated with a desire to regenerate the national morals, he besought the honour of knighthood-not, he declared, for the value of the title, but from a conviction that that dignity would give his voice more weight. In pursuit of the desired distinction, he seems to have given a great deal of trouble to the lords in waiting and secretaries of state, and probably exceeded the bounds of their patience, for, in a commendation of Earl Paulett, he admits that less-afflicted noblemen got quit of his importunities by flight. This earl, he says, in an account of his attendance at court, 'being goutish in his feet, could not run away from the Corrector as others were apt to do.' In 1754, he offered himself as a candidate to represent the city of London in parliament. In this contest, he issued the most singular addresses, referring the sheriffs, candidates, and liverymen to consider his letters and advertisements published for some time past, and especially the appendix to Alexander the Corrector's Adventures. 'If there is just ground to think that God will be pleased to make the Corrector an instrument to reform the nation, and particularly to promote the reformation, the peace, and prosperity of this great city, and to bring them into a more religious temper and conduct, no good man, in such an extraordinary case, will deny him his vote. And the Corrector's election is believed to be the means of paving the way to his being a Joseph, and an useful and prosperous man.' He also presented his possible election in the light of the fulfilment of a prophecy. But the be-wigged, and buttoned, and knee-breeched, and low-shoed electors only laughed at him. He consoled himself for the disappointment with which this new effort was attended, as in former ones, by issuing a pamphlet. The most singular of Cruden's pamphlets detailed his love adventures. He became enamoured of Miss Elizabeth Abney. The father of this lady, Sir Thomas Abney, was a successful merchant, who was successively sheriff, alderman, lord mayor of London, and one of the representatives of the city in parliament. He was a person of considerable consequence, having been one of the founders of the Bank of England, of which he was for many years a director; but his memory is especially honoured from the fact of its being interwoven with that of Dr. Watts, who resided with him at Stoke-Newington. His daughter inherited a large fortune; and to become possessed of both, became the Corrector's sanguine expectation. Miss Abney was deaf to his entreaties. For months he pestered her with calls, and persecuted her with letters, memorials, and remonstrances. When she. left home, he caused. 'praying-bills' to be distributed in various places of worship, requesting the prayers of the minister and congregation for her preservation and safe return; and when this took place, he issued further bills to the same congregations to return thanks. Finding these peculiar attentions did not produce the desired effect, he drew up a long paper, which he called a Declaration of War, in which he declared he should compass her surrender, by 'shooting off great numbers of bullets from his camp; namely, by earnest prayer to Heaven day and night, that her mind might be enlightened and her heart softened.' His grotesque courtship ended in defeat: the lady never relented. The precision and concentration of thought required in his literary labours, the compilation and several revisings of his Concordance, his verbal index of Milton's works, his Dictionary of the Holy Scriptures, his Account of the History and Excellency of the Holy Scriptures, and his daily employment on the journal in which the letters of Junius appeared, as corrector of the press, render Cruden's aberrations the more remarkable. And a still more curious circumstance, consists in the fact that his vagaries failed to efface the esteem in which he was regarded by all who knew him, more especially by his biographers, Blackburn and Chalmers; the latter of whom said of him, that he was a man to whom the religious world lies under great obligation, ' whose character, notwithstanding his mental infirmities, we cannot but venerate; whom neither infirmity nor neglect could debase; who sought consolation where only it could be found; whose sorrows served to instruct him in the distresses of others; and who employed his prosperity to relieve those who, in every sense, were ready to perish.' Are there many men more worthy of a column in the Book of Days? EXPULSION OF THE JEWS FROM ENGLANDIn the course of the year of grace, 1290, three daughters of Edward I were married. The old chroniclers relate wondrous stories of the prodigal magnificence of those nuptials; nor are their recitals without corroboration. Mr. Herbert, a late librarian of the city of London, discovered in the records of the Goldsmith's Company, the actual list of valuables belonging to Queen Eleanor, and it reads more like an extract from the Arabian Nights, than an early English record. Gold chalices, worth £292 each, an immense sum in those days, figure in it; small silver cups are valued at £118 each-what were the large ones worth, we wonder!-while diamonds, sapphires, emeralds, and rubies, sparkle among all kinds of gold and silver utensils. Modern historians refer to the old chroniclers, and this astounding catalogue of manufactured wealth, as a proof of the attainments in refinement and art which England had made at that early period. But there is a reverse to every medal, and it is much more probable that these records of valuables are silent witnesses to a great crime-the robbery and expulsion of the Jews, proving the general barbarity and want of civilisation that then prevailed. Not long before this year of royal marriages, Edward, moaning on a sick-bed, made a solemn vow, that if the Almighty should restore him to health, he would undertake another crusade against the infidels. The king recovered; but as the immediate pressure of sickness was removed, and Palestine far distant, he compromised his vow by driving the Jews out of his French province of Guienne, and seizing the wealth and possessions of the unfortunate Israelites. It may be supposed, from the wandering nature of the Jewish race, that many members of it had been in England from a very early period; but their first regular establishment in any number dates from the Norman Conquest, William having promised them his protection. The great master of romance has, in Ivanhoe, given a general idea how the Jews were treated; but there were particular horrors perpetrated on a large scale, quite unfit for relation in a popular work. In short, it may be said that when the Jews were most favoured, their condition was to our ideas intolerable; and yet it should be recorded in favour of our ancestors, that even then the Jews were rather more mildly treated in England than in the other countries of Europe. When Edward returned from despoiling and banishing the Jews of Guiemie, his subjects received him with rapturous congratulations. The constant drain of the precious metals created by the Crusades, the almost utter deficiency of a currency for conducting the ordinary transactions of life, had caused the whole nation-clergy, nobility, gentry, and commoners-to become debtors to the Jews. If the king, then, would graciously banish them from England as he had from Guienne, his subjects' debts would be sponged out, and he, of course, would be the most glorious, popular, and best of monarchs. Edward, however, did not see the affair exactly in that light. Though, in case of an enforced exodus, he would become entitled to the Jewish possessions, yet his subjects would be greater gainers by the complete abolition of their debts. In fact, the king, besides his own part of the spoil, claimed a share in that of his subjects, but after considerable deliberation the matter was thus arranged. The clergy agreed to give the king a tenth of their chattels, and the laity a fifteenth of their lands; and so the bargain was concluded to the satisfaction and gain of all parties, save the miserable beings whom it most concerned. On the 31st of August 1290, Edward issued a proclamation commanding all persons of the Jewish race, under penalty of death, to leave England before the 1st of November. As an act of gracious condescension on the part of the king, the Jews were permitted to take with them a small portion of their movables, and as much money as would pay their travelling expenses. Certain ports were appointed as places of embarkation, and safe-conduct passes to those ports were granted to all who chose to pay for them. The passes added more to the royal treasury than to the protection of the fugitives. The people-that is to say, the Christians -rose and robbed the Jews on all sides, without paying the slightest respect to the dearly-purchased protections. All the old historians relate a shocking instance of the treatment the Jews received when leaving England. Holinshed thus quaintly tells the story: A sort of the richest of them being shipped with their treasure, in a mighty tall ship which they had hired, when the same was under sail, and got down the Thames, towards the mouth of the I river, the master-mariner bethought him of a wile, and caused his men to cast anchor, and so rode at the same, till the ship, by ebbing of the stream, remained on the dry sand. The master herewith enticed the Jews to walk out with him on land, for recreation; and at length, when he understood the tide to be coming in, he got him back to the ship, whither he was drawn up by a cord. The Jews made not so much haste as he did, because they were not aware of the danger; but when they perceived how the matter stood, they cried to him for help, howbeit he told them that they ought to cry rather unto Moses, by whose conduct their fathers passed through the Red Sea; and, there-fore, if they would call to him for help, he was able to help them out of these raging floods, which now came in upon them. They cried, indeed, but no succour appeared, and so they were swallowed up in the water. The master returned with his ship, and told the king how he had used the matter, and had both thanks and rewards, as some have written. Nearly all over the world this cruel history is traditionally known among the Jews, who add a myth to it; namely, that the Almighty, in execration of the deed, has ever since caused a continual turmoil among the waters over the fatal spot. The disturbance in the water caused by the fall, on ebb-tide, at old London Bridge, was said to be the place; and when foreign Jews visited London, it was always the first wonderful sight they were taken to see. The water at the present bridge is now as unruffled as at any other part of the river, yet Dr. Margoliouth, writing in 1851, says that most of the old Jews still believe in the legend regarding the troubled waters.  There are few relics of the Jews thus driven out of England. The rolls of their estates, still among the public records, shew that the king profited largely by their expulsion. Jewry, Jew's Mount, Jew's Corner, and other similarly named localities in some of our towns, denote their once Hebrew occupants. The Jew's House at Lincoln can be undoubtedly traced to the possession of one Belaset, a Jewess, who was hanged for clipping coin, a short time previous to the expulsion. The house being forfeited to the crown by the felony, the king gave it to William de Foleteby, whose brother bequeathed it to the Dean and Chapter of Lincoln, the present possessors. Passing through so few hands, in the lapse of so many years, its history can be easier traced, perhaps, than any other of the few houses of the same age in England. The head of the doorway of this remarkable edifice, as will be seen by the illustration, forms an arch to carry the fireplace and chimney of the upper room. There seems to have been no fireplace in the lower room, there being originally but two rooms-one above, the other below. The number of banished Jews comprised about 15,000 persons of all ages. English commerce, then in its infancy, received a severe shock by the impolitic measure; nor did learning escape with-out loss. One of the expelled was Nicolaus de Lyra, who, strange to say in those bigoted days, had been admitted a student at Oxford. He subsequently wrote a commentary on the Old and New Testaments, a work that prepared the way for the Reformation. Both Wickliffe and Luther acknowledged the assistance they had received from it. And though Pope, when describing the Temple of Dulness, says: De Lyra there a dreadful front extends, both parties, at the period of the Reformation, agreed in saying: Si Lyra non lyrasset, Lutherus non saltasset If Lyra had not piped, Luther would not have danced. From the expulsion down to the period of the Commonwealth, the presence of a few Jews was always tolerated in England, principally about the court, in the capacity of physicians, or foreign agents. Early in 1656, the wise and tolerant Protector summoned a council to deliberate on the policy of allowing Jews to settle once more in England. That all parties might be represented, Cromwell admitted several lawyers, clergymen, and merchants, to aid the council in its deliberation. The lawyers declared that there was no law to prevent Jews settling in England; the clergy asserted that Christianity would be endangered thereby; and the merchants alleged that they would be the ruin of trade. Many of the arguments employed on this discussion were again used in the late debates on the admission of Jews into parliament. The council sat four days without corning to any conclusion: at last Cromwell closed it by saying, that he had sent for them to consider a simple question, and they had made it an intricate one. That he would, therefore, be guided by Providence, and act on his own responsibility. A few days afterwards, he announced to his parliament that he had determined to allow Jews to settle in England, and the affair was accomplished. In May and June 1656, a number of Jews arrived in London, and their first care was to build a synagogue, and lay out a burial-ground. The first interment on their burial-register is that of one Isaac Britto, in 1657. THE GREAT EARTHQUAKE AT LISBON IN 1755One of the most awful earthquakes ever recorded in history, for the loss of life and property thereby occasioned, was that at Lisbon on the 1st of November 1755. Although equalled, perhaps, in the New World, it has had no parallel in the Old. About nine o'clock in the morning, a hollow thunder-like sound was heard in the city, although the weather was clear and serene. Almost immediately afterwards, without any other warning, such an upheaval and overturning of the ground occurred as destroyed the greater part of the houses, and buried or crushed no less than 30,000 human beings. Some of the survivors declared that the shock scarcely exceeded three minutes in duration. Hundreds of persons lay half-killed under stones and ruined walls, shrieking in agony, and imploring aid which no one could render. Many of the churches were at the time filled with their congregations; and each church became one huge catacomb, entombing the hapless beings in its ruins. The first two or three shocks, in as many minutes, destroyed the number of lives above mentioned; but there were counted twenty-two shocks altogether, in Lisbon and its neighbourhood, destroying in the whole very nearly 60,000 lives. In one house, 4 persons only survived out of 38. In the city-prison, 800 were killed, and 1200 in the general hospital. The effects on the sea and the sea-shore were scarcely less terrible than those inland. The sea retired from the harbour, left the bar dry, and then rolled in again as a wave fifty or sixty feet high. Many of the inhabitants, at the first alarm, rushed to a new marble quay which had lately been constructed; but this proceeding only occasioned additional calamities. The quay sank down into an abyss which opened underneath it, drawing in along with it numerous boats and small vessels. There must have been some actual closing up of the abyss at this spot; for the poor creatures thus engulfed, as well as the timbers and other wreck, disappeared completely, as if a cavern had closed in upon them.  The seaport of Setubal, twenty miles south of Lisbon, was engulfed and wholly disappeared. At Cadiz, the sea rose in a wave to a height of sixty feet, and swept away great part of the mole and fortifications. At Oporto, the river continued to rise and fall violently for several hours; and violent gusts of wind were actually forced up through the water from chasms which opened and shut in the bed beneath it. At Tetuan, Fez, Marocco, and other places on the African side of the Mediterranean, the earthquake was felt nearly at the same time as at Lisbon. Near Marocco, the earth opened and swallowed up a village or town with 8000 inhabitants, and then closed again. The comparisons which scientific men were afterwards able to institute, shewed that the main centre of the disturbance was far out in the Atlantic, where the bed of the ocean was convulsed by up-and-down heavings, thereby creating enormous waves on all sides. Many of the vessels out at sea were affected as if they had struck suddenly on a sand-bank or a rock; and, in some instances, the shock was so violent as to overturn every person and everything on board. And yet there was deep water all round the ships. Although the mid-ocean may have been the 1 the flames continued for six days, and the focus of one disturbance which made itself felt as far as Africa in one direction, England in another, and America in a third, Lisbon must unquestionably have been the seat of a special and most terrible movement, creating yawning gaps in various parts of the city, and swallowing up buildings and people in the way above described. Many mountains in the neighbourhood, of considerable elevation, were shaken to their foundations; some were rent from top to bottom, enormous masses of rock were hurled from their sides, and electric flashes issued from the fissures. To add to the horrors of such of the inhabitants as survived the shocks, the city was found to be on fire in several places. These fires were attributed to various causes-the domestic fires of the inhabitants igniting the furniture and timbers that were hurled promiscuously upon them; the large wax-tapers which on that day (being a religious festival) were lighted in the churches; and the incendiary mischief of a band of miscreants, who took advantage of the terror around them by setting fire to houses in order to sack and pillage. The wretched inhabitants were either paralysed with dismay, or were too much engaged in seeking for the mangled corpses of their friends, to attend to the fire; The flames continued for six days, and the half-roasted bodies of hundreds of persons added to the horrors. Mr Mallet, in his theory of earthquakes (which traces them to a kind of earth-wave propagated with great velocity), states that the earthquake which nearly destroyed Lisbon was felt at Loch Lomond in Scotland. ' The water, without any apparent cause, rose against the banks of the loch, and then subsided below its usual level: the greatest height of the swell being two feet four inches. In this instance, it seems most probable that the amplitude of the earth-wave was so great, that the entire cavity or basin of the lake was nearly at the same instant tilted or canted up, first at one side and then at the other, by the passage of the wave beneath it, so as to disturb the level of the contained waters by a few inches just as one would cant up a bowl of water at one side by the hand.' ALL-MALLOW-TIDE CUSTOMS AT THE MIDDLE TEMPLEIn the reign of Charles I, the young gentlemen of the Middle Temple were accustomed at All-Hallow-Tide, which they considered the beginning of Christmas, to associate themselves for the festive objects connected with the season. In 1629, they chose Bulstrode Whitelocke as Master of the Revels, and used to meet every evening at St. Dunstan's Tavern, in a large new room, called 'The Oracle of Apollo,' each man bringing friends with him at his own pleasure. It was mind of mock parliament, where various questions were discussed, as in our modern debating societies; but these temperate proceedings were seasoned with mirthful doings, to which the name of Revels was given, and of which dancing appears to have been the chief. On All-Hallows-Day, ' the master [Whitelocke, then four-and-twenty], as soon as the evening was come, entered the hall, followed by sixteen revellers. They were proper handsome young gentlemen, habited in rich suits, shoes and stockings, hats and great feathers. The master led them in his bar gown, with a white staff in his hand, the music playing before them. They began with the old masques; after which they danced the Brawls, and then the master took his seat, while the revellers flaunted through galliards, corantos, French and country dances, till it grew very late. As might be expected, the reputation of this dancing soon brought a store of other gentlemen and ladies, some of whom were of great quality; and when the ball was over, the festive-party adjourned to Sir Sydney Montague's chamber, lent for the purpose to our young president. At length the court-ladies and grandees were allured-to the contentment of his vanity it may have been, but entailing on him serious expense-and then there was great striving for places to see them on the part of the London citizens. . . . To crown the ambition and vanity of all, a great German lord had a desire to witness the revels, then making such a sensation at court, and the Templars entertained him at great cost to themselves, receiving in exchange that which cost the great noble very little-his avowal that ' dere was no such nople gollege in Ghristendom as deirs.''-Memoirs of Bulstrode Whitelocke, by R. H. Whitelocke, 1860, p. 56. |