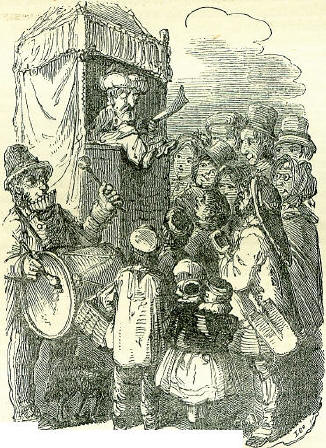

30th MarchBorn: Sir Henry Wotton, Provost of Eton College, and poetical and prose writer, 1568, Boughton Hall, Kent; Archbishop Somner, antiquary, 1606, Canterbury; Francis Pilatre de Rozier, aëronaut, 1756, Metz; Field-Marshal Henry Viscount Hardinge (Peninsular war and Sutlej campaign). 1785, Wrotham, Kent. Died: Phocion, Athenian general and statesman, B.C. 317; Cardinal Bourchier, early promoter of printing in England, 1486, Knowle, Kent; Sir Ralph Sadler, diplomatist (Sadler Papers), 1587, Standon, Herts; Dr. John King, Bishop of London, 1621; Archbishop Somner, 1669, Canterbury; Sebastian de Vauban, military engineer (fortification), 1707, Paris; Dr. William Hunter, 1783, Windmill-street, St. James's; James Morier, traveller and novelist, 1849. Feast Day: St. John Climacus, the Scholastic, abbot of Mount Sinai, 605. St. Zozimus, Bishop of Syracuse, 660. St. Regulus (or Rieul), Bishop of Sculls. SIR HENRY WOTTONBoughton Hall, in Kent, situated, as Izaak Walton tells us, 'on the brow of such a hill as gives the advantage of a large prospect, and of equal pleasure to all beholders,' was the birth-place of Sir Henry Wotton. After going through the preliminary course at Winchester School, he proceeded to Oxford, where he studied until his twenty-second year; and then, laying aside his books, he betook himself to the useful library of travel. He passed one year in France, three in Germany, and five in Italy. Wherever he stayed, to quote Walton again, 'he became acquainted with the most eminent men for learning and all manner of arts, as picture, sculpture, chemistry, and architecture; of all which he was a most dear lover, and a most excellent judge. He returned out of Italy into England about the thirtieth year of his age, being noted by many, both for his person and comportment; for indeed he was of a choice shape, tall of stature, and of a most persuasive behaviour, which was so mixed with sweet discourse and civilities as gained hint much love from all persons with whom he entered into an acquaintance.' One of his acquaintances was Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, and there can be little doubt that Wotton was, some way or another, implicated in the rash plot of that unfortunate nobleman. For when Essex was sent to the Tower, as a step so far on his way to the scaffold, Wotton thought it prudent, 'very quickly and as privately, to glide through Kent unto Dover,' and, with the aid of a fishing-boat, to place himself on the shores of France. He soon after reached Florence, where he was taken notice of by Ferdinand de Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, who sent him, under the feigned name of Octavio Baldi, on a secret mission to James VI of Scotland. The object of this mission had reference to James's succession to the English throne, and a plot to poison him, said to be entered into by some Jesuits. After remaining three months in Scotland, Wotton returned to Italy, but soon after, hearing of the death of Elizabeth, he waited on the King at London. 'Ha,' said James, when he observed him at Court, 'there is my old friend Signor Octavio Baldi.' The assembled courtiers, among whom was Wotton's brother, stared in confusion, none of them being aware of his mission to Scotland. 'Come forward and kneel, Signor Octavio Baldi,' said the king; who, on Wotton obeying, gave him the accolade, saying, 'Arise, Sir Henry Wotton.' James, as from his character may readily be supposed, highly enjoyed the state of mystification the courtiers were thrown into by the unexpected scene. Immediately after, Wotton received the appointment of ambassador to the city of Venice. It was on this journey to Venice, that Sir Henry, when passing through Augsburg, wrote in the album of his friend Flecamore, the punning and often quoted definition of an ambassador-an honest man sent to lie abroad for the good of his country. Certainly ambassadors had no good repute for veracity in those days, yet in all probability Wotton's diplomatic tactics were of a different description. On an occasion, his advice on this rather delicate question being asked, by a person setting out for a foreign embassy, he said, 'Ever speak the truth; for if you do so, you shall never be believed, and 'twill put your adversaries (who will still hunt counter) to a loss in all their disquisitions and undertakings.' For twenty years Sir Henry represented the named English court at Venice, and during that time successfully sustained the Doge in his resistance to the aggression of the Papal power. And finally returning to his native country, he received what Thomas Fuller styles, 'one of the genteelest and entirest preferments in England,' the Provostship of Eton College. To Wotton's many accomplishments was added a rich poetical taste, which he often exercised in compositions of a descriptive and elegiac character. He also delighted in angling, finding it, 'after tedious study, a cheerer of his spirits, a diverter of sadness, a calmer of unquiet thoughts, a moderator of passions, a procurer of contentedness; and that it begat habits of peace and patience in those who professed and practised it.' So when settled down in life as Provost of Eton, he built himself a neat fishing-lodge on the banks of the Thames, where he was often visited by his friend and subsequent biographer, Walton. The site is still occupied by a fishing-lodge, though not the one that Wotton erected. It is on an island, a green lawn sloping gently down to the pleasant river. On one side, the turrets of Windsor Castle are seen, through a vista of grand old elm trees; on the other the spires and antique architecture of Eton Chapel and College. The property still belongs to the College, and it is said that it never has been untenanted by a worthy and expert brother of the angle since the time of Wotton. And there it was, 'with peace and patience cohabiting in his heart,' as Walton tells us, that Sir Henry, when beyond seventy years of age, 'made this description of a part of the present pleasure that possessed him, as he sat quietly, on a summer's evening, on a bank a-fishing. It is a description of the Spring; which, because it glided as softly and sweetly from his pen as that river does at this time, by which it was then made, I shall repeat it unto you: This day dame Nature seemed in love; The lusty sap began to move; Fresh juice did stir th' embracing vines, And birds had drawn their valentines. The jealous trout, that low did lie, Rose at a well-dissembled fly; There stood my friend, with patient skill Attending on his trembling quill. Already were the eaves possest With the swift pilgrim's daubed nest; The groves already did rejoice In Philomel's triumphant voice; The showers were sport, the weather mild, The morning fresh, the evening smiled. Joan takes her neat-rubbed pail, and now She trips to milk the sand-red cow, Where, for some sturdy foot-ball swain, Joan strokes a syllabub or twain. The fields and gardens were beset With tulips, crocus, violet: And now, though late, the modest rose Did more than half a blush disclose. Thus all looks gay, and full of cheer, To welcome the new-liveried year. As Sir Henry, in the quiet shades of Eton, found himself drawing towards the end of life, he felt no terror; he was only inspired with hope for the future and kindly remembrances of the past. Among these last, was the wish to revisit the school where he had played and studied when a boy; so for this purpose he travelled to Winchester, and here is his commentary: How useful was that advice of a holy monk, who persuaded his friend to perform his customary devotions in a constant place, because in that place we usually meet with those very thoughts which possessed us at our last being there. And I find it thus far experimentally true; that, at my now being in that school, and seeing that very place, where I sat when I was a boy, occasioned me to remember those very thoughts of my youth which then possessed me; sweet thoughts indeed, that promised my growing years numerous pleasures, without mixtures of cares; and those to be enjoyed when time (which I then thought slow-paced) had changed my youth into manhood. But age and experience have taught me that those were but empty hopes. For I have always found it true, as my Saviour did foretell, 'sufficient for the day is the evil thereof.' Returning to Eton from this last visit to Winchester, he died in 1639, and was buried in the College chapel, according to his own direction, with no other inscription on his tomb than HERE LIES THE AUTHOR OP THIS SENTENCE: THE ITCH OP DISPUTATION IS THE SCAB OF THE CHURCH. We translate the inscription, for, strange to say, the original Latin words were incorrectly written, and, as gossiping Pepys tells us, so basely altered that they disgrace the stone. THE SICILIAN VESPERSOn this day, five hundred and eighty years ago, the people of Sicily rescued themselves from the tyranny of a foreign dynasty by an insurrection which has become a celebrated event in history, and which presents some points of resemblance to the revolution in the same island which we have so recently witnessed. In our time the Neapolitan tyrant was a Prince of the French house of Bourbon; at the most distant period he was of the French house of Anjou. The secret prompter of it was in the both cases an Italian patriot, -Garibaldi in 1860, and in 1282 John of Procida. It is difficult to say in which the tyranny had been most galling, but in the earlier period the revolt was directed with less skill, and was carried on with greater ferocity. Sicily and Naples were at that time ruled by a conqueror and usurper, to whom they had been handed over by the will of a pope, and they were occupied by a French soldiery, of whose unbounded greediness and brutal licentiousness, the properties and persons of the inhabitants of all ranks were the prey. In Sicily, more even than in the continental provinces of Naples, the Italians were subjected, without any chance of redress, to the oppressions of their French rulers; and almost incredible anecdotes are told by the old chroniclers of the manner in which they were treated. They were attacked especially in that pointon which all people feel sensitive, the honours of their wives and daughters. A French baron named Ludolph, who was governor of Menone, is said to have taken by force a young girl every week to satisfy his passions; and a knight of Artois Faramond, who commanded in Noto, made a regular practice of causing all the handsomest women of his government to be brought to his palace, where they were sacrificed to his violence. John of Procida, who had been himself robbed of his lands by the French, was indefatigable in his efforts to rouse the spirits of the Sicilians, secretly visited and encouraged their chiefs, and secured the aid of the King of Arragon, Don Pedro, who was tempted by the prospect of obtaining for himself the crown of Sicily, to which he made out a claim through his wife. Yet, though John of Procida had made the Sicilians eager for revolt, we have no reason for supposing that there was any organised plan of insurrection, when it burst out suddenly and by accident; and we must probably ascribe in a great measure to this circumstance the sanguinary character which it assumed. The 30th of March in the year 1282 was Easter Monday, and, as was customary on such festive occasions, the people of Palermo deter-mined to go in procession to hear vespers at a church a short distance out of the town. The French looked upon all such gatherings with suspicion, and caused the people thus assembled to be searched for arms, which appears to have been made a pretext by the French soldiery for insulting the Sicilian females. Such was the case on the present occasion. As a young lady of great beauty, and the daughter of a gentleman of condition, was proceeding to the church, a French soldier laid hands upon her, and, under pretence of ascertaining if she had weapons concealed under her dress, offered her publicly a brutal insult. Her screams threw the multitude into a furious excitement, and, led by her father and husband and their friends, they seized what-ever weapons came to hand, and massacred the whole of the French in Palermo, sparing neither sex nor age. To such a degree had the hatred of the population been excited, that even the monks issued from their monasteries to encourage and assist in the slaughter. Saint Remi, the governor of Palermo, attempted to make his escape in disguise, but was taken and killed, and the father of the young lady whose insult had been the signal for the rising, was chosen governor of the city for the Sicilians. This signal, once given, was quickly acted upon in other parts of the island. The same day similar massacres took place in Monté Reale, Conigio, Carini, Termini, and other neighbouring towns; on the morrow, the example spread to Cefaladi, Mazaro, and Marsala; and on the 1st of April at Gergenti and Liceta. Burciao, the governor of Marsala, had just issued an order to the inhabitants of his government, to bring in all their gold and silver to the royal treasury, when the insurgents came to put him to death; and Louis de Montpellier, governor of San Giovanni, was poignarded by an injured husband, and his corpse hung out ignominiously at the castle window. Another unprovoked insult led to the revolt of Catania on the 4th of April. A young Frenchman named Jean Viglemada, notorious for his libertinism, attempted to take liberties with a lady named Julia Villamelli, when he was prevented by the unexpected entrance of her husband, whom he slew. The lady rushed through the street screaming for vengeance; and the people assembled, and, falling furiously on the Frenchmen, made a horrible carnage of them. Fight thousand are said to have perished in the massacre; all who escaped sought refuge in a strong fortress, where some perished with hunger and the rest were killed in attempting to leave it in disguise. The people of Palermo had meanwhile raised troops, and with these they laid siege to Taormina, took the place by assault, and slaughtered the whole of its French garrison. Messina alone remained in the possession of the French, and this was soon lost by their own imprudence. A citizen named Collura, supposed to have been employed by conspirators, made his appearance armed in the most public place of the town. As the Sicilians had been forbidden under the most severe penalties to carry or even possess arms, this was an act of defiance to the French authority, and four archers came to take the offender to prison. He offered a vigorous resistance, and some friends came to his assistance. The municipal authorities, believing that the citizens were not strong enough to overcome the French garrison, assisted in arresting the rioters, who, after an obstinate struggle, were all secured and committed to prison. The affair would probably have ended here, but the viceroy, not satisfied with imprisoning the men who had resisted his officers, sent to seize their wives also; and the citizens, provoked at this act of injustice, flew to arms, and, taking the French unprepared, massacred about three thousand of them. The rest retired into the fortresses, which were taken by assault, and their defenders put to, the sword. The fate of the viceroy is a matter of doubt. Such are the circumstances, as far as known, of this celebrated insurrection, which, from the circumstance of its having begun on the occasion of a public procession of the people of Palermo to attend vespers, received the name of the Sicilian Vespers. It is stated by some of the old writers that the numbers of the French who perished in the massacres throughout the island were not less than from twenty-four to twenty-eight thousand; but this number is supposed by historical writers to be greatly exaggerated. The King of Naples, Charles of Anjou, was at Monte-Fiascone, treating with the Pope, when the news of these events was brought to him, and he was so overcome with rage and indignation that it was some time before he could speak, but he gnawed a cane which he used to carry in his hand, and rolled his eyes furiously from side to side. When at length he opened his mouth, it was to give vent to frightful threats against the 'traitorous' Sicilians. But from that time nothing prospered with him. While the Pope laboured to overwhelm the insurgents with his excommunications, the King assembled an immense force, and laid siege to Messina, the inhabitants of which were reduced to propose terms of capitulation; but the conditions he insisted on imposing were so harsh that they resolved on continuing their defence, which they did until they were relieved by the King of Arragon, who had now thrown off the mask, and arrived with a numerous fleet. Charles was obliged to raise the siege of Messina, and nearly the whole naval armament was taken or destroyed by the Arragonese. Don Pedro had already been crowned King of Sicily at Palermo. In the war which followed, Charles had to submit to defeats and disappointments until he died in 1285, not only deprived of Sicily, but threatened by revolt in Naples. MARRIAGE OF ELIZA SPENCERSir John Spencer, Lord Mayor of London in 1594, was a citizen of extraordinary wealth. At his death, March 30, 1609, he was said to have left £800,000, a sum which must have appeared utterly fabulous in those days. His funeral was attended by a prodigious multitude, including three hundred and twenty poor men, who each had a large dole of eatable, drinkable, and wear-able articles given him. Ten years before his death, 'Rich Spencer,' as he was called, had his soul crossed by a daughter, who insisted upon giving her hand to a slenderly endowed young nobleman, the Lord Compton. It seems to have been a rather perilous thing for a citizen in those times to thwart the matrimonial designs of a nobleman, even towards a member of his own family. On the 15th March 1598-9, John Chamberlain, the Horace Walpole of his day, as far as the writing of gossipy letters is concerned, adverted in one of his epistles to the troubles connected with the love affairs of Eliza Spencer. 'Our Sir John Spencer,' says he, 'was the last week committed to the Fleet for a contempt, and hiding away his daughter, who, they say, is contracted to the Lord Compton; but now he is out again, and by all means seeks to hinder the match, alleging a pre-contract to Sir Arthur Henningham's son. But upon his beating and misusing her, she was sequestered to one Barker's, a proctor, and from thence to Sir Henry Billingsley's, where she yet remains till the matter be tried. If the obstinate and self-willed fellow should persist in his doggedness (as he protests he will), and give her nothing, the poor lord should have a warm catch.' Sir John having persisted in his self-willed course of desiring to have something to say in the disposition of his daughter in marriage, the young couple became united against his will, and for some time he steadily refused to take Lady Compton back into his good graces. At length a reconciliation was effected by a pleasant stratagem of Queen Elizabeth. When Lady Compton had her first child, the queen requested that Sir John would join her in standing as sponsors for the first offspring of a young couple happy in their love, but discarded by their father; the knight readily complied, and her Majesty dictated her own surname for the Christian name of the child. The ceremony being performed, Sir John assured the Queen that, having discarded his own daughter, he should adopt this boy as his son. The parents of the child being introduced, the knight, to his great surprise, discovered that he had adopted his own grandson; who, in reality, became the ultimate inheritor of his wealth. There is extant a curious characteristic letter of Lady Compton to her husband, apparently written on the paternal wealth coming into their hands: My swede Life, Now I have declared to you my mind for the settling of your state, I supposed that it were best for me to bethink, or consider with myself, what allowance were meetest for me. For, considering what care I ever had of your estate, and how respectfully I dealt with those, which, by the laws of God, of nature, and civil polity, wit, religion, government, and honesty, you, my clear, are bound to, I pray and beseech you to grant to me, your most kind and loving wife, the sum of £1600 per annum, quarterly to be paid. Also, I would (besides the allowance for my apparel) have £600 added yearly (quarterly to be paid) for the performance of charitable works, and those things I would not, neither will, he accountable for. Also, I will have three horses for my own saddle, that none shall dare to lend or borrow; none lend but I; none borrow but you. Also, I would have two gentlewomen, lest one should be sick, or have some other lett. Also, believe that it is an indecent thing for a gentlewoman to stand mumping alone, when God hath blessed their lord and lady with a great estate. Also, when I ride a-hunting, or hawking, or travel from one house to another, I will have them attending; so, for either of these said women, I must and will have for either of them a horse. Also, I will have six or eight gentlemen; and I will have my two coaches,-one lined with velvet, to myself, with four very fair horses, and a coach for my women, lined with cloth; one laced with gold, the other with scarlet, and laced with watch-lace and silver, with four good horses. Also, I will have two coachmen; one for my own coach, the other for my women's. Also, at any time when I travel, I will be allowed, not only carriages and spare horses for me and my women, but I will have such carriages as shall be fitting for all, or duly; not pestering my things with my women's, nor theirs with chambermaids', or theirs with washmaids'. Also, for laundresses, when I travel, I will have them sent away with the carriages, to see all safe; and the chambermaids I will have go before with the grooms, that the chambers may be ready, sweet, and clean. Also, for that it is indecent to crowd up myself with my gentleman usher in my coach, I will have him to have a convenient horse to attend me either in city or country; and I must have two footmen; and my desire is, that you defray all the charges for me. And, for myself (besides my yearly allowance), I would have twenty gowns of apparel; six of them excellent good ones, eight of them for the country, and six others of them very excellent good ones. Also, I would have put into my purse £2000 and £200, and so you to pay my debts. Also, I would have £6,000 to buy me jewels, and £4, 000 to buy me a pearl chain. Now, seeing I have been and am so reasonable unto you, I pray you do find my children apparel, and their schooling; and all my servants, men and women, their wages. Also, I will have all my houses furnished, and all my lodging-chambers to be suited with all such furniture as is fit; as beds, stools, chairs, suitable cushions, carpets, silver warming-pans, cupboards of plate, fair hangings, and such like. So, for my drawing-chamber, in all houses, I will have them delicately furnished, both with hangings, couch, canopy, glass, chairs, cushions, and all things thereunto belonging. Also, my desire is, that you would pay your debts, build Ashby-house, and purchase lands, and lend no money (as you love God) to the Lord Chamberlain, which would have all, perhaps your life, from you. Remember his son, my Lord Waldou, what entertainment he gave me when you were at Tilt-yard. If you were dead, he said, he would marry me. I protest I grieve to see the poor man have so little wit and honesty, to use his friends so vilely. Also, he fed me with untruths concerning the Charter-house; but that is the least: he wished me much harm; you know him. God keep you and me from him, and such as he is. So, now that I have declared to you what I would have, and what that is I would not have, I pray, when you be an earl, to allow use £1,000 more than now desired, and double attendance. Your loving wife, Eliza Compton. THE PASSOVER OF THE MODERN JEWSJewish life, which. is every day losing its originality in towns, has still preserved in some village communities on the Continent its strong traditional impress. It is among the Vosges mountains and on the banks of the Rhine that we must look for the superstitious, singular customs, and patriarchal simplicity of ancient Judea. Having an invitation to witness the festival of Paecach at the house of a fine old Jew, at Bolwiller, near Basle, I set off on the fourteenth of their month Nisan, corresponding to our 29th of March, to be ready for the ceremony which was to celebrate the flight of Israel from Egypt with their kneading troughs upon their shoulders. Hence its name of the 'Feast of Azymes,' or unleavened bread. As I was passing down the street, I marked the first sign; children were running in all directions with baskets of bottles, the presents of the rich tradespeople to the rabbi, schoolmaster, beadle, &c., of wine of the best quality, that the poor as well as the rich may make merry. My host received me on the threshold with the classical salutation, 'Alechem Salem,' 'Peace be with you,' and I was soon in the midst of his numerous family, who had just concluded the week's preparations. These consist of the most extensive washings and cleanings; every cup to be used must be boiled in water, the floors are washed and sprinkled with red and yellow sand; the Matses, or Passover cakes, are kneaded by robust girls, on immense tables near the flaming stove; others take it from the bright copper bowls, roll it out into the round cakes, prick and bake it. Enormous chaplets of onions are hung round the kitchen, and shining tin plates are ranged by dozens on the shelves, to be used only at the Passover. White curtains adorn every window; the seven-branched lamp is brought out; the misrach, a piece of paper on which this word, meaning east, is written, is reframed and hung on the side of the room towards Jerusalem, in which direction they turn at prayer; the raised sofa on which the master of the house passes the first two nights is fitted with cushions. Our conversation was interrupted by the three knocks of the Schulekopfer, who comes to each house to call the faithful to prayer; we followed him immediately, and found the synagogue splendidly illuminated, and when the service was over, each family returned home to hold the seder, the most characteristic ceremony of the festival. The table in the dining-room was covered with a cloth, the lamp lighted, plates were set, but no dishes; on each plate a small book was laid, called the Haggada, in Hebrew, consisting of the chants and prayers to be used, and illustrated with engravings of the departure of the Israelites from Egypt. My host took the sofa at the head of the table, his wife and daughters were on one side, his sons on the other, all dressed in new clothes, and their heads covered. At the end of the table I noticed an angular-faced man in far-worn clothes. I found he was a sort of beggar who always partook of Herr Salomon's festivals. In the middle of the table, on a silver dish, were laid three Passover-cakes, separated by a napkin; above these, on smaller dishes, was a medley of lettuce, marmalade flavoured with cinnamon, apples, and almonds, a bottle of vine-gar, some chervil, a hard-boiled egg, horse-radish, and at one side a bone with a little flesh on it. All these were emblems: the marmalade signified the clay, chalk, and bricks in which the Hebrew slaves worked under Pharaoh; the vine-gar and herbs, the bitterness and misery they then endured; and the bone the paschal lamb. Each. guest had a silver cup; the master's was of gold; on a side-table were several bottles of Rhenish Falernian; the red recalling the cruelty of Pharaoh, who, tradition says, bathed in the blood of the Hebrew children. The master of the house opened the ceremony with the prayer of blessing; the cups having first been filled to the brim, then the eldest son rose, took a ewer from another table, and poured water over his father's hands, all present rising and stretching out their hand to the centre dish, repeating these words from the Haggada: 'Behold the bread of sorrow our fathers ate in Egypt! Whoever is hungry let him come and eat with us. Whoever is poor let him take his Pass-over with us.' The youngest son asks his father in Hebrew, 'What is the meaning of this ceremony? ' and his father replies, 'We were slaves in Egypt, and the Lord our God has brought us out with a mighty hand and a stretched out arm.' All then repeated the story of the departure from Egypt in Bible words, and tasted the various symbolical articles arranged in the dish. By the side of the master's cup stood one of much larger dimensions, which was now filled with the best wine; it is set apart for the prophet Elijah, the good genius of Israel, an invisible guest it is true, but always and everywhere present at high festivals. Thus ends the first part of the seder: the evening meal is set on the table, good cheer and cheerful conversation follow. At a certain time every one resumes his former position, and the table is arranged as at the first. Herr Salomon returns to his cushions, and half a Passover-cake covered with a napkin is laid before him, which division typifies the passage of the Red Sea; he gave a piece of it to each. A prayer followed, and he then desired his eldest son to open the door. The young man left his place, opened the door into the corridor very wide, and stood back as if to let some one pass. The deepest silence prevailed; in a few minutes the door was closed, the prophet had assuredly entered, he had tasted the wine which was exclusively set apart for him, and sanctified the house by his presence as God's delegate. The cups of wine are now emptied for the fourth time; the 115th, 116th, 118th, and 150th Psalms are sung with their traditional in-flexions; and each rivals his neighbour in spirit and voice; the women even are permitted to join on this evening, though prohibited at all other times. Thus ends the religious part of the festival, but the singing continues, the libations become more and more copious; at nine the women retire, and leave the men, until the influence of the Rhenish wine reminds them it is time to separate. The usual evening prayer is never offered on this night and the following one; they are special occasions, when God watches, as formerly in Egypt, over all the houses of the Jews. The ceremonies we have described are repeated on the following day, which is a great festival. All the people go early to the synagogue in their new clothes. Dinner is prepared at noon, and the afternoon is devoted to calling on friends; the dessert remains on the table, and a plate and glass of wine are presented to each guest with the hospitable salutation, 'Baruch-haba,' 'Blessed be he who cometh.' The feast lasts a week, but four days are only half feasts, during which the men attend to necessary business, and the women pay visits, and make the arrangements for marriages, which are scarcely ever concluded without the intervention of a marriage agent, who receives so much from the dowry at the completion of the affair. On bidding adieu to my host at the conclusion of the feast, he begged me to be careful during my journey, as we were in the time of omer. This is the interval between the Passover and Pentecost, the seven weeks elapsing from the departure from Egypt and the giving of the law, marked in former days by the offering of an omer of barley daily at the temple. Now there is no offering, but all the villagers after the evening prayer count the days, and look forward to its close with a sort of impatience; it is considered a fearful time, during which. a thousand extraordinary events take place, and when every Jew is particularly exposed to the influence of evil spirits. There is something dangerous and fatal in the air; every one should be on the watch, and not tempt the schedim (demons) in any way; the smallest and most insignificant things require attention. These are some of the recommendations given by Jewish mothers to their children: 'Do not whistle during the time of omer, or your mouth will be deformed; if you go out in your shirt sleeves, you will certainly come in with a lame arm; if you throw stones in the air, they will fall back upon you.' Let not men of any age ride on horseback, or in a carriage, or sail in a boat; the first will run away with you, the wheels of the second will break, the last will take in water. Have a strict eye upon your cattle, for the sorcerers will get into your stables, mount your cows and goats, bring diseases upon them, and turn their milk sour. In the latter case, try to lay your hand upon the suspected person, shut her up in a room with a basin of the sour milk, and beat the milk with a hazel wand, pronouncing God's name three times. Whilst you are doing this, the sorceress will make great lamentation, for the blows are falling upon her. Only stop when you see blue flames dancing on the surface of the milk, for then the charm is broken. If at nightfall a beggar comes to ask for a little charcoal to light his fire, be very careful not to give it, and do not let him go without drawing him three times by his coat tail, and without losing time, throw some large handfuls of salt on the fire. This beggar is, probably, a sorcerer, for they seize upon every pretext, and take all disguises to enter into your houses. Such are the dangers of omer. PRETENDED MURDERS OF CHRISTIAN CHILDREN BY THE JEWSThe Christians of the middle ages, especially in the west of Europe, regarded the Jews with bitter hatred, and assailed them with horrible calumnies, which served as the excuses for persecution and plunder. One of the most frequent of these calumnies was the charge of stealing Christian children, whom, on Good Friday, or on Easter day, they tormented and crucified in the same way that Christ was crucified, in despite of the Saviour and of all true believers. Rumours of such barbarous atrocities were most frequent during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle informs us, under the year 1137, how, 'in his (King Stephen's) time, the Jews of Norwich bought a Christian child before Easter, and tortured him with all the same torture with which our Lord was tortured; and on Long Friday (the name among the Anglo-Saxons and Scandinavians for Good Friday) hanged him on a rood for hatred of our Lord, and afterwards buried him. They imagined it would be concealed, but our Lord shewed that he was a holy martyr. And the monks took him and buried him honourably in the monastery; and through our Lord he makes wonderful and manifold miracles, and he is called St. William.' The writer of this was contemporary with the event, and, although his testimony is no proof that the child was murdered by the Jews, it leaves no doubt of the fact of their being accused of it, or of the advantage which the English clergy took of it. The later chroniclers, John of Bromton, and Matthew of Westminster, repeat the story, and represent it as occurring in the year 1145. The Roman Catholic Church made a saint of Hugh, who, they say, was twelve years of age, and had been apprenticed to a tanner, and his martyrdom is commemorated in the calendar on the 24th of March. The words of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle would seem to shew that the old practice of selling children for slaves continued to exist at Norwich in the time of Stephen. St. William's shrine at Norwich was long an object of pilgrimage; and the people of that city built and dedicated a chapel to him in ThorpWood, near Norwich, where his body is said to have been found. A child is said to have been put to death in the same manner by the Jews of Gloucester, in the year 1160; and again, in the year 1181, the Jews of Bury St. Edmunds are accused of having crucified a child named Robert, on Easter day, at whose shrine in the church there numerous miracles were believed to be performed. Two years afterwards, Philippe Auguste, King of France, banished the Jews from his kingdom on a similar charge, which was again brought against the Jews of Norwich in 1235 and 1240, on which charge several Jews were punished. Matthew of Westminster states that the Jews of Lincoln circumcised and crucified a Christian child in 1250, at whose tomb miracles were performed; but this is perhaps only a mistake of date for the more celebrated child martyr, whose story we will now relate. As the story is related by Matthew Paris,-who also, it must be remarked, lived at the time of the event: The Jews of Lincoln, about the feast of Peter and Paul (June 29), stole a Christian child eight years of age, whose name was Hugh, and kept him secretly till they had given information to all the Jews throughout England, who sent deputies to be present at the ceremony of crucifying him. This was alleged to have been done with all the particularities which attended the passion of our Saviour. The mother of the child, meanwhile, was in great distress, went about the city inquiring for it, and, informed that it had been last seen playing with some Jewish children and entering a certain Jew's house there, she suddenly entered the Jew's house, and discovered the body of her child thrown into a well. The alarm was given to the citizens, who forced the house, and carried, away the body of the murdered child. In the middle of this tumult, King Henry's Justiciary, John de Lexington, was in Lincoln, and he caused the Jew who lived in this house, and was called Copin, to be seized and strictly examined. Copin, on a pardon for his life and limbs, made a confession of all the circumstances of the murder, and declared that it was the custom of the Jews thus to sacrifice Christian children every year. The canons of Lincoln obtained the body of the child, and buried it under a shrine in their cathedral, and for ages, according to the belief of the Catholic Church, miracles continued to be performed at the tomb of St. Hugh. That the public circumstances of this story took place,-namely, that the Jews of Lincoln were accused of murdering a child under these circumstances, that many of them were imprisoned and brought to punishment on this charge, and that the body of the child was buried honourably in Lincoln Cathedral, there is no room for doubt. In the Chronicle of London, known as the Liber de Antiquis Legibus, it is stated that on St. Cecilia's day (Nov. 22), then a Monday, ninety-two Jews were brought from Lincoln to Westminster, accused of having slain a male Christian child, and were all committed to the Tower of London. There is a peculiar interest attached to this event, from the circumstance that it appears to be the first instance we know in which the right of a foreigner to be tried by a mixed jury was insisted upon, in this case unsuccessfully. The London Chronicle, by a contemporary writer, adds, 'of which number eighteen, who refused to submit to the verdict of Christians without Jews, when the king was at Lincoln, and when they were indicted for that murder before the king, were the same day drawn, and after dinner in the evening hanged. The rest were sent back to the Tower.' Official documents relating to these Jews in the Tower are also printed in Rymer's Faedera. A ballad in Anglo-Norman has been preserved in the National Library in a contemporary manuscript, and has been printed by M. Francisque Michel in a little volume entitled Hugues de Lincoln, which gives an account of the pretended martyrdom of the child ' St. Hugh,' resembling generally the narrative of Matthew Paris, except that it gives considerably more details of the manner in which the child was treated. But the most remarkable proof of the firm hold which this story had taken upon men's minds in the middle ages is the existence of a ballad, more romantic in its details, which has been preserved orally down to our own time, and is still recited from time to time in Scotland and the north of England. Several copies of it have been printed from oral recitation, among our principal collections of old ballads, of which perhaps the best is that given by Jamieson. HUGH OF LINCOLN Four and twenty bonny boys Were playing at the ba'; And by it came him, sweet sir Hugh, And he play'd o'er them a'. He kick'd the ha' with his right foot, And catch'd it wi' his knee; And throuch-and-thro' the Jew's window, He gar'd the bonny ha' flee. He's done him to the Jew's castell, And walk'd it round about; And there he saw the Jew's daughter At the window looking out. Throw down the ha', ye Jew's daughter, Throw down the ba' to me! Never a bit,' says the Jew's daughter, Till up to me come ye.' How will I come up? How can I come up? How can I come to thee? For as ye did to my auld father, The same ye'll do to me.' She's game till her father's garden, And pu'd an apple, red and green; 'Twas a' to wyle him, sweet sir Hugh, And to entice him in. She's led him in through ac dark door, And sae has she thro' nine; She's laid him on a dressing table, And stickit him like a swine. And first came out the thick thick blood, And syne came out the thin; And syne came out the bonny heart's blood; There was nae mair within. She's row'd him in a cake o' lead, Bade him lie still and sleep; She's thrown him in Our Lady's draw-well, Was fifty fathom deep. When bells were rung, and mass was sung, And a' the bairns came hame, When every lady gat hame her son, The Lady Maisry gat nano. She's ta'en her mantle her about, Her coffer by the hand; And she's game out to seek her son, And wander'd o'er the land. She's done her to the Jew's castell, Where a' were fast asleep; 'Gin ye be there, my sweet sir Hugh, I pray you to me speak.' She's done her to the Jew's garden, Thought he had been gathering fruit; 'Gin ye be there, my sweet sir Hugh, I pray you to me speak.' She near'd Our Lady's deep draw-well, Was fifty fathom deep; Where'er ye be, my sweet sir Hugh, I pray you to me speak.' Gae hame, gae hame, my mither dear; Prepare my winding sheet; And, at the back o' merry Lincoln, The morn I will you meet.' Now lady Maisry is gane hame; Made him a winding sheet; And, at the back o' merry Lincoln, The dead corpse did her meet. And a' the bells o' merry Lincoln, Without men's hands, were rung; And a' the books o' merry Lincoln, Were read without man's tongue; And ne'er was such a burial Sin Adam's days begun. THE BORROWED DAYSIt was on the 30th of March 1039, that the Scottish covenanting army, under the Marquis of Montrose, marched into Aberdeen, in order to put down a reactionary movement for the king and episcopacy which had been raised in that city. The day proved a fine one, and therefore favourable for the march of the troops, a fact which occasioned a thankful surprise in the friends of the Covenant, since it was one of the Borrowed Day's, which usually are ill. One of their clergy alluded to this in the pulpit, as a miraculous dispensation of Providence in favour of the good cause. The Borrowed Days are the three last of March. The popular notion is, that they were borrowed by March from April, with a view to the destruction of a parcel of unoffending young sheep-a purpose, however, in which March was not successful. The whole affair is conveyed in a rhyme thus given at the firesides of the Scottish peasantry: March said to Aperill, I see three hoggs'' upon a hill, And if you'll lend me dayes three, I'll find a way to make them dee. The first o' them was wind and weet, The second o' them was snaw and sleet, The third o' them was sic a freeze, It froze the birds' nebs to the trees: When the three days were past and gave, The three silly hoggs came hirpling' hame. Sir Thomas Browne, in his Vulgar Errors, alludes to this popular fiction, remarking, 'It is usual to ascribe unto March certain Borrowed Daies from April.' But it is of much greater antiquity than the time of Browne. In the curious book entitled the Complaynt of Scotland, printed in 1548, occurs the following passage: There eftir i entrit in ane grene forest, to contempill the tender yong frutes of grene treis, becaus the borial blastis of the thre borouing dais of March hed chaissit fragrant flureise of cvyrie frut-tree far athourt the fieldis.' Nor is this all, for there is an ancient calendar of the church of Rome often quoted by Brand, t in which allusion is made to 'the rustic fable concerning the nature of the month [March]; the rustic names of six days which shall follow in April, or may be lase in March. No one has yet pretended fully to explain the origin or meaning of this fable. Most probably, in our opinion, it has taken its rise in the observation of a certain character of weather prevailing about the close of March, somewhat different from what the season justifies; one of those many wintry relapses which belong to the nature of a British spring. This idea we deem to be supported by Mrs. Grant's account of a similar superstition in the Highlands: The Faoilleoch, or those first days of February, serve many poetical purposes in the Highlands. They are said to have been borrowed for some purpose by February from January, who was bribed by February with three young sheep. These three days, by Highland reckoning, occur between the 11th and 15th of February; and it is accounted a most favourable prognostic for the ensuing year that they should be as stormy as possible. If these days should be fair, then there is no more good weather to be expected through the spring. Hence the Faoilteaeh is used to signify the very ultimatum of bad weather. FANTOCCINIIn the simulative theatricals of the streets, the Fantoccini, when they existed, might be considered as the legitimate drama; Punch as sensational melodrama. The Punch puppets, as is well known-but what a pity it should be known!-are managed by an unseen performer below the stage, who has his fingers thrust up within their dresses, so as to move the head and arms only. In the case of the Fantoccini, all the figures have moveable joints, governed by a string, and managed by a man who stands behind the scene, passing his arms above the stage, and so regulating the action of his dramatis persona. The Fantoccini were in considerable vogue in the bye streets of London in the reign of George IV, on the limited scale represented by our artist. Turks, sailors, clowns, &c., dangled and danced through the scene with great propriety of demeanour, much to the delight of the young, and the gaping wonderment of strangers.  Few persons who gazed upon the grotesque movements of these figures imagined the profound age of their invention. The Fantoccini, introduced as a novelty within our own remembrance, in reality had its chief features developed in the days of the Pharaohs; for in the tombs of ancient Egypt, figures have been found whose limbs were made moveable for the delight of children before Moses was born. In the tombs of Etruria similar toys have been discovered; they were disseminated in the East; and in China and India are now made to act dramas, either as moveable figures, or as shadows behind a curtain. As 'ombres Chinoises' these figures made a novelty for London sightseers at the end of the last century; and may still be seen on winter nights in London performing a brief, grotesque, and not over-delicate drama, originally produced at Astley's Amphitheatre, and there known as The Broken Bridge.' It requires considerable dexterity to 'work' these figures well; and when several are grouped together, the labour is very great, requiring a quick hand and steady eye. The exhibition does not 'pay' now so well as Punch; because it is too purely mechanical, and lacks the bustle and fun, the rough practical joking and comicality of that great original creation. The proprietors of these shows complain of this degenerate taste; but it is as possible for the manager of a street show to be in advance of the taste of his audience, as for the manager of a Theatre Royal; and the sensation dramas' now demanded by the theatre-goers, are to better plays what Punch is to the Fantoccini. |