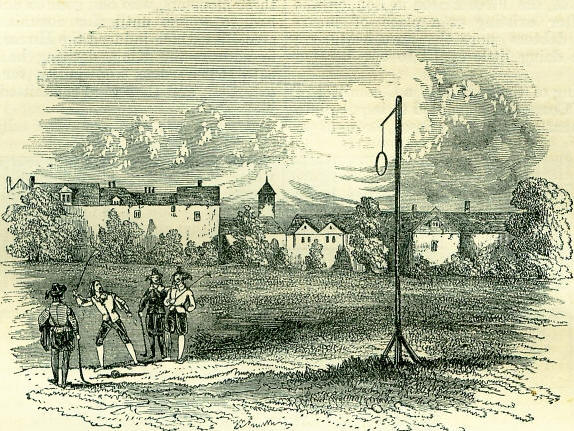

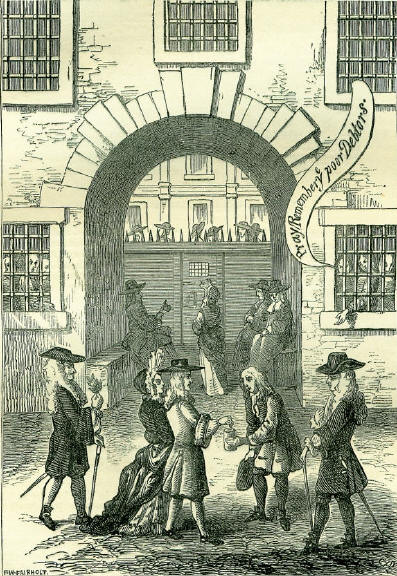

2nd AprilBorn: C. N. Oudinot, Marshal of France, Duke of Reggio, 1767, Bar-sur-Ornain (sometimes the 25th is given as the date). Died: Arthur, Prince of Wales, 1502, Ludlow; Jean Barth, French naval commander, 1702; Thomas Carte, historian, 1754, Yattendon; Comte de Mirabeau, 1791, Paris; Dr. James Gregory, professor of medicine, author of 'Conspectus Medicinae,' 1821, Edinburgh; John Le Keux, architectural engraver, 1846. Feast Day: St. Apian, of Lycia, martyr, 306. St. Theodosia, of Caesarea, martyr, 308. St. Nicetius, archbishop of Lyons, 577. St. Ebba, or Abba, abbess, martyr, 874. B. Constantine, King of Scotland, 874. St. Bronacha, of Ireland. St. Francis of Paula, founder of the order of Minims, 1508. ARTHUR, PRINCE OF WALESKing Henry VII, the first of our Tudor monarchs, had three sons, Arthur, Henry, and Edmond, the last of whom died in his childhood. Arthur was born on the 20th of September 1486, at Winchester. His birth was the subject of universal joy throughout the kingdom, as in him were united the claims of the rival houses of York and Lancaster, and the general satisfaction was soon increased by the early display of precocious talents, and of a gentle and amiable disposition. In 1489, Arthur was created Prince of Wales. This title, as given to the king's eldest son, had been created originally as a measure of conciliation towards the Welsh, and it would be still more gratifying to that people when the House of Tudor came to the throne. The House of York had also, before its attainment of royalty, had close relations with Wales; and Edward IV, as a stroke of wise policy, had sent his eldest son to reside in his great castle of Ludlow, on the border, and had established there a court of government for Wales and the Marches, which had now become permanent. Henry VII, in continuation of this policy, sent his son, Prince Arthur, to Ludlow, to reside there under the governance of a distant relative of the Tudor family, named Sir Rhys ap Thomas, and Ludlow Castle became Arthur's home. Little is said of the actions of the youthful prince, except that his good qualities became more and more developed, until the year 1501, when, in the month of November, Arthur, who had just completed his fifteenth year, was married with great ceremony to Catherine of Arragon, a Spanish princess, then in her eighteenth year. The young prince and his bride repaired to Ludlow immediately after the marriage, which he survived but a short time, dying in Ludlow Castle, on the 2nd of April 1502. His corpse was conveyed in solemn procession to Worcester, and was there buried in the cathedral, and a rich shrine, which still remains, raised over the tomb. The untimely death of this amiable prince was the subject of sincere and universal grief, but indirectly it led to that great revolution which gave to England her present religious and ecclesiastical forms. Henry VII, for political reasons, and on the plea that the marriage had never been consummated, married the widow of Arthur to his younger brother Henry, who became afterwards King Henry VIII. Henry, who subsequently declared that the marriage was forced upon him, divorced his wife, and the dispute, as every one knows, was, under the direction of Providence, the cause of the separation of the English church from Rome. In a somewhat similar manner the untimely death of Henry, Prince of Wales, the son of James I, led perhaps indirectly to that great convulsion in the middle of the following century, to which we owe the establishment of the freedom of the English political constitution. A GROUP OF OLD LADIESDied at Edinburgh, on the 2nd of April 1856, Miss Elizabeth Gray, at the age of 108, having been born in May 1748. That cases of extra-ordinary longevity are seldom supported by clear documentary evidence has been very justly alleged; it has indeed been set forth that we scarcely have complete evidence for a single example of the centenarian. In this case, however, there was certainly no room for doubt. Miss Gray had been known all her life as a member of the upper circle of society in the Scottish metropolis, and her identity with the individual Elizabeth Gray, the daughter of William Gray, of Newholm, writer in Edinburgh, whose birth is chronicled in the register of her father's parish of Dolphington, in Lanarkshire, as having occurred in May 1748, is beyond dispute in the society to which the venerable lady belonged. It may be remarked that she was a very cheerful person, and kept up her old love of whist till past the five score. Her mother attained ninety-six, and two of her sisters died at ninety-four and ninety-six respectively. She had, however, survived her father upwards of a hundred years, for he died in 1755; nay, a more remarkable thing than even this was to be told of Betty Gray-a brother of hers (strictly a half-brother) had died so long ago as 1728. A faded marble slab in the wall of Dolphington Kirk, which records the decease of this child-for such he was-must have been viewed with strange feelings, when, a hundred and twenty-eight years later, the age-worn sister was laid in the same spot. Little more than two years after the death of Miss Gray, there died in Scotland another centenarian lady, about whose age there could be no ground for doubt, as she had lived in the eye of intelligent society all her days. This person was the Hon. Mrs. Hay Mackenzie, of Cromartie. She died in October 1858, at the age of 103; she was grandmother to the present Duchess of Sutherland; her father was the sixth Lord Elibank, brother and successor of Lord Patrick, who entertained Johnson in Edinburgh; her maternal grandfather was that unfortunate Earl of Cromartie who so narrowly escaped accompanying Kilmarnock and Balmerino to the scaffold in 1746. She was a most benevolent woman-a large giver-and enjoyed universal esteem. Her conversation made the events of the first half of the eighteenth century pass as vividly before the mind as those of the present day. It was remarked as a curious circumstance, that of Dunrobin Castle, the place where her grandfather was taken prisoner as a rebel, her granddaughter became mistress. It is well known that female life is considerably more enduring than male; so that, although boys are born in the proportion of 105 to 100 of girls -a fact that holds good all over Europe-there are always more women in existence than men. It really is surprising how enduring women some-times become, and how healthily enduring too, after passing the more trying crises of female existence. Mrs. Piozzi, who herself thought it a person's own fault if they got old, gives us in one of her letters a remarkable case of vigorous old-ladyism. I must tell you,' says she, 'a story of a Cornish gentlewoman hard by here [Penzance], Zenobia Stevens, who held a lease under the Duke of Bolton by her own life only ninety-nine years-and going at the term's end ten miles to give it up, she obtained permission to continue in the house as long as she lived, and was asked of course to drink a glass of wine. She did take one, but declined the second, saying she had to ride home in the twilight upon a young colt, and was afraid to make herself giddy-headed.' The well known Countess Dowager of Cork, who died in May 1840, had not reached a hundred -she had but just completed her ninety-fourth year-but she realized the typical character of a veteran lady who, to appearance, was little affected by age. Till within a few days of her death she was healthy and cheerful as in those youthful days when she charmed Johnson and Boswell, the latter of whom was only six years her senior. She was in the custom to the last of dining out every day when she had not company at home. As to death, she always said she was ready for him, come when he might; but she did not like to see him coming. Lady Cork was daughter of the first Lord Galway, and she lived to see the sixth, her great grand-nephew. Mr. Francis Brokesby, who writes a letter on antiquities and natural curiosities from Shottesbrooke in 1711. (published by Hearne in connection with Leland's Itinerary, vi. 104), mentions several instances of extremely protracted female life. He tells of a woman then living near the Tower in London, aged about 130, and who remembered Queen Elizabeth. Hearne himself subsequently states that this woman was Jane Scrimshaw, who had lived for four score years in the Merchant Tailors' alms-houses, near Little Tower-hill. She was, he says, born in the parish of Mary-le-Bow, London, on the 3rd of April 1584, so that she was then in the 127th year of her age, 'and likely to live much longer.' She, however, died on the 26th of December 1711. It is stated that even at the last there was scarcely a grey hair on her head, and she never lost memory or judgment. Mr. Brokesby reported another venerable person as having died about sixty years before-that is, about 1650--who attained the age of a hundred and forty. She had been the wife of a labouring man named. Humphry Broadhurst, who resided at Hedgerow, in Cheshire, on the property of the Leighs of Lyme. The familiar name she bore, The Cricket in the hedge, bore witness to her cheerful character; a peculiarity to which, along with great temperance and plainness of living, her great age was chiefly to be attributed. A hardly credible circumstance was alleged of this woman, that she had borne her youngest child at four score. Latterly, having been reduced by gradual decay to great bodily weakness, she used to be carried in the arms of this daughter, who was herself sixty. She was buried in the parish church of Prestbury. It was said of this woman that she remembered Bosworth Field; but here there must be some error, for to do so in 1650, she would have needed to be considerably more than 140 years old, the battle being fought in 1485. It is not unlikely, however, that her death took place earlier than 1650, as the time was only stated from memory. THE GAME OF PALL MALLApril 2nd, 1661, Pepys enters in his Diary, 'To St. James's Park, where I saw the Duke of York playing at Pelemele, the first time that I over saw the sport.' The Duke's brother, King Charles II, had recently formed what is called the Mall in St. James's-park for the playing of this game, which, however, was not new in England, as there had previously existed a walk for the purpose (lined with trees) on the ground now occupied by the street called Pall Mall. It was introduced from France, probably about the beginning of the seventeenth century; but the derivation of the name appears to be from the Italian, Palamaglio, i. e., palla, a ball, and maglio, a mallet; though we derived the term directly from the French Palemaille. The game answers to this name, the object being by a mallet to drive a ball along a straight alley and through an elevated ring at the end: victory being to him who effects this object at the smallest number of strokes. Thus pall-mall may be said in some degree to resemble golf, being, however, less rustic, and more suitable for the man of courts. King Charles II would appear to have been a good player. In Waller's poem on St. James's Park, there is a well-known passage descriptive of the Merry Monarch engaged in the sport: Here a well-polished mall gives us the joy, To see our Prince his matchless force employ; His manly posture and his graceful mien, Vigour and youth in all his motions seen; No sooner has he touched the flying ball, But 'tis already more than half the mall. And such a fury from his arm has got, As from a smoking culverin 'twere shot.'  The phrase 'well polished' leads to the remark that the alley for pall-mall was hardened and strewn with pounded shells, so as to present a perfectly smooth surface. The sides of the alley appear to have been boarded, to prevent the ball from going off the straight line. We do not learn anywhere whether, as in golf, mallets of different shapes and weights were used for a variety of strokes,-a light and short one, for instance, for the final effort to ring the ball. There is, however, an example of a mallet and ball preserved in London from the days when they were employed in Pall Mall; and they are here represented. The game was one of a commendable kind, as it provoked to exercise in the open air, and was of a social nature. It is rather surprising that it should have so entirely gone out, there being no trace of it after the Revolution. The original alley or avenue for the game in London began, even in the time of the Commonwealth, to be converted into a street-called, from the game, Pall Mall-where, if the reader will pardon a very gentle pun, clubs now take the place of mallets. THE FLEET PRISON OF OLDApril 2nd, 1844, the Fleet Prison in London was abolished, after existing as a place of incarceration for debtors more than two centuries; all that time doing little credit to our boasted civilization. In the spring of the year 1727 a Committee of the House of Commons, appointed to inquire into the management of Debtors' prisons, brought to light a series of extortions and cruelties practiced by the jailers towards the unfortunate debtors in their charge, which now appear scarcely credible, but which were not only true, but had been practised continually for more than a century by these monsters, who had gone on unchecked from bad to worse, until this commission disclosed atrocities which induced the House of Commons to address the King, desiring he would prosecute the wardens and jailers for cruelty and extortion, and they were committed prisoners to Newgate.  Hogarth has chosen for the subject of one of his most striking pictures the examination of the acting warden of the Fleet-Thomas Bambridge -before a Committee of the House of Commons. In the foreground of the picture a wretched prisoner explains the mode by which his hands and neck were fastened together by metal clamps. Some of the Committee are examining other instruments of torture, in which the heads and necks of prisoners were screwed, and which seem rather to belong to the dungeons of the Inquisition than to a debtors' prison in the heart of London. Bainbridge and his satellites had used these tortures to extort fees or bribes from the unfortunate debtors; at the same time allowing full impunity to the dishonest, whose cash he shared. At the conclusion of the investigation, the House unanimously came to the conclusion that he had willfully permitted several debtors to escape; had been guilty of the most notorious breaches of trust, great extortions, and the highest crimes and misdemeanors in the execution of his office; that he had arbitrarily and unlawfully loaded with irons, put into dungeons, and destroyed, prisoners for debt under his charge, treating them in the most barbarous and cruel manner, in high violation and contempt of the laws of the kingdom. Yet this wretch, probably by means of the cash he had accumulated in his cruel extortions, managed to escape justice, dying a few years afterwards, not as he might and ought to have done, at Tyburn, but by his own hands. When the Commissioners paid their first and unexpected visit to the Fleet prison, they found an unfortunate baronet, Sir William Rich, confined in a loathsome dungeon, and loaded with irons, because he had given some slight offence to Bambridge. Such was the fear this man's cruelty excited, that a poor Portuguese, who had been manacled and shackled in a filthy dungeon for months, on being examined before the Commissioners, and surmising wrongly, from something said, that Bambridge might return to his post, 'fainted, and the blood started out of his mouth and nose.' Thirty-six years before this Committee gave the death-blow to the cruel persecution which awaited an unfortunate debtor, the state of this and other prisons was fully exposed in a little volume, 'illustrated with copper plates,' and termed The Cries of the Oppressed. The frontispiece gives the curious view of the interior of the Prison, here produced on a larger scale. It is a unique view in old London, and gives the general aspect of the place, its denizens and its visitors, in 1691, when the plate was engraved. In the foreground, some persons of the better class, who may have come to visit friends, are walking; and one male exquisite, in a wig of fashionable proportions, carries some flowers, and perhaps a few scented herbs, to prevent 'noisome smells ' (which we learn were very prevalent in the jail) from injuring his health. A charitable gentleman places in the begging-box some cash for the benefit of the destitute prisoners, who are seen at grated windows clamouring for charity. In the archway which connects the forecourt with the prisoners' yard, are seated some visitors waiting their turn; a female is about to leave the jail, and walks towards the jailer, seated on the opposite bench, who bears the key of the gate in his hand; the gate is provided with a grated opening, through which to examine and question applicants for admission; the wall is surmounted by a formidable row of spikes; and over these (by aid of a violent use of perspective) we see the hats of those who walk Farringdon Street, or Fleet Market, as it was then called, the view being bounded by the old brick houses opposite the prison. Moses Pitt, who published this, now rare little volume, was at one time an opulent man. He rented from Dr. Fell, Bishop of Oxford, 'the printing house called the Theatre' in the time of Charles the Second, where he commenced an Atlas in 12 vols. folio, and, as he says, 'did in the latter end of King Charles's time print great quantities of Bibles, Testaments, Common-prayers, &c., whereby I brought down the price of Bibles more than half, which did great good at that time, popery being then likely to overflow us.' His troubles began in building speculations at Westminster, in King Street, Duke Street, and elsewhere. He tells that he 'also took care to fill up all low grounds in that part of St. James's Park between the bird-cages and that range of buildings in Duke Street, whose back front is toward the said park.' He erected a great house in Duke Street, which he let to the famed Lord Chancellor Jefferies; but the Revolution prevented him from getting a clear title to all the ground, though Sir Christopher Wren, the King's Architect, had begun to negotiate the matter. Then creditors came on Pitt, and a succession of borrowings, and lawsuits consequent thereto, led rapidly to his incarceration in the Fleet Prison for debt. Pitt's book is the result of communications addressed to 65 debtors' prisons in England. It is, as he says, 'a small book as full of tragedies as pages; they are not acted in foreign nations among Turks and Infidels, Papists and Idolaters, but in this our own country, by our own country-men and relations to each other,-not acted time out of mind, by men many thousand or hundred years agone; but now at this very day by men now living in prosperity, wealth, and grandeur; they are such tragedies as no age or country can parallel.' He, among many others, narrates the case of Mr. Morgan, a surgeon of Liverpool, who, being put in prison there, was ultimately reduced so low by poverty, neglect, and hunger, as to catch by a cat mice for his sustenance. On his complaining of the barbarity of his jailer, instead of redress, he was beaten and put into irons. In the Castle of Lincoln, one unfortunate, because he had asked for a purse the jailers had taken from him, he being destitute thereby, was treated to 'a ride in the jailer's coach,' as they termed it; that is, he was placed in a hurdle, with his head on the stones, and so dragged about the prison yard, 'by which ill-usage he so became not altogether so well in his intellects as formerly.' From Appleby, in Westmoreland, an unfortunate debtor writes, 'Certainly no prisoners' abuses are like ours. Our jail is but eight yards long, and four and a half in breadth, without any chimney, or place of ease; several poor prisoners have been starved and poisoned in it; for whole years they cannot have the benefit of the air, or fires, or refreshment.' It was the custom of the jailers to charge high fees for bed or lodging; to force prisoners to purchase from them all they wanted for refreshment at extortionate charges, to continually demand gratuities, and to ill-treat and torture all who would not or could not gratify their rapacity. One wretched man at St. Edmundbury jail, for daring to send out of the prison for victuals, had thumbscrews put upon him, and was chained on tip-toe by the neck to the wall. All these cruelties resulted from the easy possibility of making money. The office of prime warden was let at a large price, and the money made by forced fees. The debtor was first taken to a sponging-house, charged enormously there; if too poor to pay, removed to the prison, but subjected to high charges for the commonest necessaries. Even if he lived 'within the rules,' as the privileged houses of the neighbourhood were termed, he was always subjected to visits from jailers, who would declare his right to that little liberty forfeit unless their memory was refreshed by a fee. The Commission already alluded to remedied much of this, but still gross injustice remained in many minor instances. The state of the prison in 1749 may be gathered from a poem, entitled 'The Humours of the Fleet,' written by a debtor, the son of Dance, the architect of old Buckingham House and of Guy's Hospital. It is 'adorned' with a frontispiece showing the prison yard and its denizens. A new-comer is treating the jailer, cook, and others to drink; others play at rackets against the high brick-wall, which is furnished with a formidable row of spikes at right angles with it, and above that a high wooden hoarding. A pump and a tree in one corner do not obliterate the unpleasant effect of the ravens who are feeding on garbage thrown about. The author describes the dwellers in this 'poor, but merry place,' the joviality consisting in ill-regulated, noisy companionship. Some, we are told, play at rackets, or wrestle; others stay indoors at billiards, backgammon, or whist. Some, of low taste, ring hand-bells, direful noise! And interrupt their fellows' harmless joys; Disputes more noisy now a quarrel breeds, And fools on both sides fall to loggerheads: Till wearied with persuasive thumps and blows. They drink to friends, as if they ne'er were foes. The prisoners had a mode of performing rough justice among themselves on disturbers of the general peace, by taking the offending parties to the common yard, and well drenching them beneath the pump! Such the amusement of this merry jail, Which you'll not reach, if friends or money fail: For ere its three-fold gates it will unfold, The destined captive must produce some gold; Four guineas at the least for different fees Completes your Habeas, and commands the keys; Which done and safely in, no more you're bled. If you have cash, you'll find a friend and bed; But that deficient, you'll but ill betide, Lie in the hall, perhaps, or common side. 'The chamberlain' succeeded the jailers, and he expected a 'tip,' or gratuity, to shew proper lodgings; a ' master's fee,' consisting of the sum of £1 2s. 8d., had then to be paid for the privilege of choosing a decent room. This, however, secured nothing, as the wily chamberlain, When paid, puts on a most important face, And shows Mount-scoundrel as a charming place. This term was applied to wretched quarters on the common side at the top of the building, where no one stayed if he could avoid it; hence 'this place is first empty, and the chamberlain commonly shews this to raise his price upon you for a better.' A fee of another half-guinea induces him to shew better rooms, for which half-a-crown a-week rent has to be paid; unless 'a chum' or companion be taken who shares the charge, and sponges on the freshman; for generally 'the chum' was an old denizen, who made the most of new-comers. The one our author describes seems to have startled him by his appearance; but the chamberlain comforts him with the assurance: The man is now in dishabille and dirt, He shaves tomorrow though, and turns his shirt. The first night is spent over a heavy supper and drinking bout, ordered lavishly by the old stager and jailers, and paid for by the new-comer. One custom may be noted in the words of this author as a 'wind-up to a day in prison.' He tells us that 'Watchmen repeat Who goes out? from half an hour after nine, till St. Paul's clock strikes ten, to give visitors notice to depart; when the last stroke is given, they cry All told; at which time the gates are locked, and nobody suffered to go out upon any account.' The cruelties which had been repeatedly complained of from 1586 by the poor prisoners, who charged the wardens with murder and other misdemeanours, continued unchecked in the midst of London until 1727. The simpler, but still unwarrantable extortions, which we have described from Dance's poem, as existing in 1749, continued with very little modification until the suppression of the jail in 1844. The same may be said of other debtors' jails in the kingdom. All good rules were abandoned or made of no avail by winking at their breakage. Thus, spirituous liquors were not permitted to be brought in by visitors for prisoners' use, yet dram-shops were established in the prison itself, under the name of ' tape shops,' where liquor at an advanced charge might be bought, under the name of white or red tape, as gin, rum, or brandy was demanded. In the same way game, not allowed to be sold outside, was publicly sold inside the prison's walls. Any luxuries or extravagances might be obtained by a dishonest or rich prisoner. The rules for living outside were equally lax, and though the person who availed himself of the privilege was supposed to never go beyond their precincts, country trips were often taken, if paid for: one of the denizens of the rules of the King's Bench, a sporting character of the name of Hetherington, drove the coach from London to Birmingham for more than a month consecutively, during the illness of his friend the coach-man, for whom he often 'handled the ribbons.' On festival occasions, such as Easter Monday, the prisoners invited their friends, who came in shoals; and 'the mirth and fun grew fast and furious' during the day; hopping in sacks, foot-races, and other games were indulged in, and on one occasion a mock election was got up within the walls, which has been immortalized on canvas by the artist, B. R. Haydon, then in the King's Bench for debt. It was considered one of his best works, was purchased for £500 by King George the Fourth, and is now at Windsor Castle. DR. GREGORY AND THE MODERATE MANDr. James Gregory, Professor of the Practice of Physic in the University of Edinburgh, was a man of vigorous talents and great professional eminence. He was what is called a starving doctor, and, not long after his death, the following anecdote was put in print, equally illustrative of this part of the learned professor's character, and of the habits of life formerly attributed to a wealthy western city: |