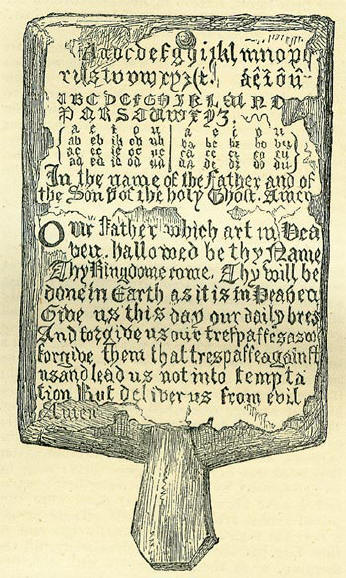

3rd JanuaryBorn: Marcus Tullius Cicero, B.C. 107; Douglas Jerrold, 1803. Died: Jeremiah Horrox, mathematician, 1641; George Monk, Duke of Albemarle, 1670; Josiah Wedgwood, 1795; Charles Robert Maturin, novelist, 1842; Eliot Warburton, historical novelist, 1852. Feast Day: St. Peter Balsam martyr, 311; St. Anterus, pope, 235 St. Gordius, martyr; St. Geneviève, virgin. ST. GENEVIÈVESainte Geneviève, who has occupied, from the time of her death to the present day, the distinguished position of Patroness Saint of the city of Paris, lived in the fifth century, when Christianity, under corrupted forms, was contending with paganism for domination over the minds of rude and warlike races of men. Credible facts of this early period are few, obscure, and not easily separated from the fictions with which they have been combined; but the following principal events of the life of St. Geneviève may be taken as probably authentic: She was born in the year 422, at Nanterre, a village about four miles from Paris. At the early age of seven years she was consecrated to the service of religion by St. Germanus, bishop of Auxerre, who happened to pass through the village, and was struck with her devotional manners. At the age of fifteen years she received the veil from the hands of the Archbishop of Paris, in which city she afterwards resided. By strict observance of the services of the Church, and by the practice of those austerities which were then regarded as the surest means of obtaining the blessedness of a future state, she acquired a reputation for sanctity which gave her considerable influence over the rulers and leaders of the people. When the Franks under Clovis had subdued the city of Paris, her solicitations are said to have moved the conqueror to acts of clemency and generosity. The miracles ascribed to St. Geneviève may be passed over as hardly likely to obtain much credence in the present age. The date of her death has been fixed on January 3rd, 512, five months after the decease of king Clovis. She was buried near him in the church of St, Peter and St. Paul, since named the church of Sainte Genevieve. The present handsome structure was completed in 1764. During the revolutionary period it was withdrawn from the services of religion, and named the Pantheon, but has since been restored to ecclesiastical uses and to its former name of Sainte Genevieve. Details of her life are given in Bollandus's 'Acta Sanctorum,' and in Butler's 'Lives of the Saints.' MARCUS TULLIUS CICEROCicero, like nearly every other great man, gives in his life a testimony to the value and necessity of diligent culture of the mind for the attainment of eminence. His education for oratory was most laborious. He himself declared that no man ought to pretend to the character of an orator without being previously acquainted with everything worth knowing in nature and art, as eloquence unbased upon knowledge is no better than the prattle of a child. He was six-and-twenty before e considered himself properly accomplished for his profession. ' He had learned the rudiments of grammar and languages from the ablest teachers; gone through the studies of humanity and the politer letters with the poet Archias; been instructed in philosophy by the principal professors of each sect-Phaedrus the Epicurean, Philo the Academic, and Diodotus the Stoic; acquired a perfect knowledge of the law from the greatest lawyers as well as the greatest statesmen of Rome, the two Scaevolas; all which accomplishments were but ministerial and subservient to that on which his hopes and ambition were singly placed, the reputation of an orator. To qualify himself therefore for this, he attended the pleadings of all the speakers of his time; heard the daily lectures of the most eminent orators of Greece, and was perpetually composing somewhat at home, and declaiming under their correction; and, that he might neglect nothing which might in any degree help to improve and polish his style, he spent the intervals of his leisure in the company of the ladies; especially of those who were remarkable for a politeness of language, and whose fathers had been distinguished by a fame and reputation for eloquence. While he studied the law, therefore, under Scaevola the augur, he frequently conversed with his wife Laelia, whose discourse, he says, was tinctured with all the elegance of her father Laelius, the politest speaker of his age: he was acquainted politest with her daughter Mucia, who married the great orator Lucius Crassus; and with her granddaughters the two Liciniae, who all excelled in that delicacy of the Latin tongue which was peculiar to their families, and valued themselves on preserving and propagating it to their posterity.'-Melmoth's Life of Cicero. GENERAL MONKThe most curious portion of Monk's private history is his marriage to Anne, daughter of John Clarges, a farrier in the Savoy in the Strand. She was first married to Thomas Radford, late farrier: they lived at the Three Spanish Gipsies in the New Exchange, Strand, and sold wash-balls, powder, gloves, &c., and she taught plain work to girls. In 1647 she became seamstress to Monk, and used to carry him linen. In 1649 she and her husband fell out and parted; but no certificate of any parish-register appears recording his burial. In 1652 she was married at the Church of St. George, Southwark, to General Monk, though it is said her first husband was living at the time. In the following year she was delivered of a son, Christopher, who 'was suckled by Honour Mills, who sold apples, herbs, oysters, &c.' The father of 'Nan Clarges,' according to Aubrey's Lives (written about 1680), had his forge upon the site of No. 317, on the north side of the Strand. 'The shop is still of that trade,' says Aubrey; 'the corner shop, the first turning, on y° right hand, as you come out the Strand into Drury Lane: the house is now built of brick.' The house alluded to is believed to be that at the right-hand corner of Drury Court, now a butcher's. The adjoining house, in the court, is now a whitesmith's, with a forge, &c. Nan's mother was one of Five Women Barbers, celebrated in her time. Nan is described by Clarendon as a person ' of the lowest extraction, without either wit or beauty; 'and Aubrey says 'she was not at all handsome nor cleanly,' and that she was seamstress to Monk, when he was imprisoned in the Tower. She is known to have had great control and authority over him. Upon his being raised to a dukedom, and her becoming Duchess of Albemarle, her father, the farrier, is said to have raised a Maypole in the Strand, nearly opposite his forge, to commemorate his daughter's good fortune. She died a few days after the Duke, and is interred by his side in Henry the Seventh's Chapel, Westminster Abbey. The Duke was succeeded by his son, Christopher, who married Lady Elizabeth Cavendish, grand-daughter of the Duke of Newcastle, and died childless. The Duchess' brother, Thomas Clarges, was a physician of note; was created a baronet in 1674, and was ancestor to the baronets; whence is named Clarges Street, Piccadilly. JOSIAH WEDGWOOD Josiah Wedgwood, celebrated for his valuable improvements in the manufacture of earthenware, was born July 12th 1730, at Burslem, in Stafford-shire, where his father and others of the family had for many years been employed in the potteries. At the early age of eleven years, his father being then dead, he worked as a thrower in a pottery belonging to his elder brother; and he continued to be thus employed till disease in his right leg compelled him to relinquish the potter's wheel, and ultimately to have the limb cut off below the knee. He then began to occupy himself in making imitations of agates, jaspers, and other coloured stones, by combining metallic oxides with different clays, which he formed into knife-handles, small boxes, and ornaments for the mantelpiece. After various movements in business, he finally settled in a pottery of his own, at Burslem, where he continued for a time to make the small ornamental articles which had first brought him into notice, but by degrees began to manufacture fine earthenware for the table. He was successful, and took a second manufactory, where he made white stoneware; and then a third, where he produced a delicate cream-coloured ware, of which he presented some articles to Queen Charlotte, who was so well pleased with them and with a complete service which he executed by order, that she appointed him her potter. The new kind of earthenware, under the name of Queen's ware, became fashionable, and orders from the nobility and gentry flowed in upon him. He took into partnership Mr. Bentley, son of the celebrated Dr. Bentley, and opened a warehouse in London, where the goods were exhibited and sold. Mr. Bentley, who was a man of learning and taste, and had a large circle of acquaintance among men of rank and science, superintended the business in the metropolis. Wedgwood's operations in earthenware and stoneware included the production of various articles of ornament for the cabinet, the drawing-room, and the boudoir. To facilitate the conveyance of his goods, as well as of materials required for the manufacture, he contributed a large sum towards the formation of the Trent and Mersey Canal, which was completed in 1770. On the bank of this canal, while it was in progress, he erected, near Stoke, a large manufactory and a handsome mansion for his own residence, and there he built the village of Etruria, consisting chiefly of the habitations of his workmen. He died there on the 3rd of January 1795, in the 65th year of his age. He was married, and had several children. To Wedgwood originally, and to him almost exclusively during a period of more than thirty years, Great Britain was indebted for the rapid improvement and vast extension of the earthen-ware manufacture. During the early part of his life England produced only brown pottery and common articles of white earthenware for domestic use. The finer wares for the opulent classes of society, as well as porcelain, were imported from Holland, Germany, and France. He did not extend his operations to the manufacture of porcelain-the kaolin, or china-clay, not having been discovered in Cornwall till he was far advanced in life; but his earthenware were of such excellence in quality, in form, and in beauty of ornamentation, as in a great degree to supersede the foreign china-wares, not only in this country, but in the markets of the civilized world. Wedgwood's success was the result of experiments and trials, conducted with persevering industry on scientific principles. He studied the chemistry of the aluminous, silicious, and alkaline earths, colouring substances, and glazes, which he employed. He engaged the most skilful artisans and artists, and superintended assiduously the operations of the work-shop and the kiln. In order to ascertain and regulate the heat of his furnaces, he invented a pyrometer, by which the higher degrees of temperature might he accurately measured: it consisted of small cylinders of pure white clay, with an apparatus which showed the degrees of diminution in length which the cylinders underwent from the action of the fire. Besides the manufacture of the superior kinds of earthenware for the table and domestic purposes, he produced a great variety of works of fine art, such as imitations of cameos, intaglios, and other antique gems, vases, urns, busts, medallions, and other objects of curiosity and beauty. His imitations of the Etruscan vases gained him great celebrity, and were purchased largely. He also executed fifty copies of the Portland vase, which were sold for fifty guineas each. DOUGLAS JERROLD No one that has seen Douglas Jerrold can ever forget him-a tiny round-shouldered man, with a pale aquiline visage, keen bright grey eyes, and a profusion of iron-brown hair; usually rather taciturn (though with a never-ceasing play of eye and lips) till an opportunity occurred for shooting forth one of those flashes of wit which made him the conversational chief of his day. The son of a poor manager haunting Sheerness, Jerrold owed little to education or early connection. He entered life as a midshipman, but early gravitated into a London literary career. His first productions were plays, whereof one, based on the ballad of 'Black-eyed Susan' (written when the author was scarce twenty), obtained such success as redeemed theatres and made theatrical reputations, and yet Jerrold never realised from it above seventy pounds. He also wrote novels, but his chief productions were contributions to periodicals. In this walk he had for a long course of years no superior. His 'Caudle Lectures', contributed to Punch, were perhaps the most attractive series of articles that ever appeared in any periodical work. The drollery of his writings, though acknowledged to be great, would not perhaps have made Douglas Jerrold the remarkable power he was, if he had not also possessed such a singular strain of colloquial repartee. In his day, no man in the metropolis was one half so noted for the brilliancy and originality of his sayings. Jerrold's wit proved itself to be, unlike Sheridan's, unpremeditated, for his best sayings were answers to remarks of others; often, indeed, they consisted of clauses or single words deriving their significancy from their connection with what another person had said. Seldom or never did it consist of a pun or quibble. Generally, it derived its value from the sense lying under it. Always sharp, often caustic, it was never morose or truly ill-natured. Jerrold was, in reality, a kind-hearted man, full of feeling and tenderness; and of true goodness and worth, talent and accomplishment, he was ever the hearty admirer. Specimens of conversational wit apart from the circumstances which produced them, are manifestly placed at a great disadvantage; yet some of Jerrold's good things bear repetition in print. His definition of dogmatism as 'puppyism come to maturity,' might be printed by itself in large type and put upon a church-door, without suffering any loss of point. What he said on passing the flamingly uxorious epitaph put up by a famous cook on his wife's tomb-'Mock Turtle!' -might equally have been placed on the tomb itself with perfect preservation of its poignancy. Similarly independent of all external aid is the keenness of his answer to a fussy clergyman, who was ex-pressing opinions very revolting to Jerrold,--to the effect that the real evil of modern times was the surplus population- 'Yes, the surplice population.' It is related that a prosy old gentleman, meeting him as he was passing at his usual quick pace along Regent Street, poised himself into an attitude, and began: 'Well, Jerrold, my dear boy. what is going on?' 'I am,' said the wit, instantly shooting off. Such is an example of the brief fragmentary character of the wit of Jerrold. On another occasion it consisted of but a mono-syllable. It was at a dinner of artists, that a barrister present, having his health drunk in connection with the law, began an embarrassed answer by saying he did not see how the law could be considered as one of the arts, when Jerrold jerked in the word ' black,' and threw the company into convulsions. A bore in company remarking how charmed he was with the Prodigue, and that there was one particular song which always quite carried him away,-' Would that I could sing it!' ejaculated the wit. What a profound rebuke to the inner consciousness school of modern poets there is in a little occurrence of Jerrold's life connected with a volume of the writings of Robert Browning! When recovering from a violent fit of sickness, he had been ordered to refrain from all reading and writing, which he had obeyed wonderfully well, although he found the monotony of a seaside life very trying to his active mind. One morning he had been left by Mrs. Jerrold alone, while she had gone shopping, and during her absence a parcel of books from London arrived. Among them was Browning's 'Sordello,' which he commenced to read. Line after line, and page after page was devoured by the convalescent wit, but not a consecutive idea could he get from that mystic production. The thought then struck him that he had lost his reason during his illness, and that he was so imbecile that he did not know it. A perspiration burst from his brow, and he sat silent and thoughtful. When his wife returned, he thrust the mysterious volume into her hands, crying out, 'Read this, my dear!' After several attempts to make any sense out of the first page or so, she returned it, saying, 'Bother the gibberish! I don't understand a word of it!' 'Thank Heaven,' cried the delighted wit; 'then I am not an idiot! His winding up a review of Wordsworth's poems was equally good. 'He reminds me,' said Jerrold,' of the Beadle of Parnassus, strutting about in a cocked hat, or, to be more poetical, of a modern Moses, who sits on Pisgah with his back obstinately turned to that promised land the Future; he is only fit for those old maid tabbies, the Muses! His Pegasus is a broken-winded hack, with a grammatical bridle, and a monosyllabic; bit between his teeth!' Mr. Blanchard Jerrold, in his Life of his father, groups a few additional good things which will not here be considered superfluous. 'A dinner is discussed. Douglas Jerrold listens quietly, possibly tired of dinners, and declining pressing invitations to be present. In a few minutes he will chime in, 'If an earthquake were to engulf England tomorrow, the English would manage to meet and dine somewhere among the rubbish, just to celebrate the event.' A friend drops in, and walks across the smoking-room to Douglas Jerrold's chair. The friend wants to rouse Mr. Jerrold's sympathies in behalf of a mutual acquaintance who is in want of a round sum of money. But this mutual friend has already sent his hat about among his literary brethren on more than one occasion. Mr. ---'s hat is becoming an institution, and friends were grieved at the indelicacy of the proceeding. On the occasion to which I now refer the bearer of the hat was received by my father with evident dissatisfaction. 'Well,' said Douglas Jerrold, 'how much does - want this time?' 'Why, just a four and two noughts will, I think, put him straight,' the bearer of the hat replied. Jerrold-'Well, put me down for one of the noughts.' 'The Chain of Events,' playing at the Lyceum Theatre, is mentioned. 'Humph!' says Douglas Jerrold. 'I'm afraid the manager will find it a door chain, strong enough to keep everybody out of the house.' Then some somewhat lackadaisical young members drop in. They assume that the Club is not sufficiently west; they hint at something near Pall-Mall, and a little more style. Douglas Jerrold rebukes them. ' No, no, gentlemen; not near Pall-Mall: we might catch coronets.' A stormy discussion ensues, during which a, gentleman rises to settle the matter in dispute. Waving his hands majestically over the excited disputants, he begins: 'Gentlemen, all I want is common sense.' 'Exactly,' says Douglas Jerrold, 'that is precisely what you do want.' The discussion is lost in a burst of laughter. The talk lightly passes to the writings of a certain Scot. A member holds that the Scot's name should be handed down to a grateful posterity. Douglas Jerrold- 'I quite agree with you that he should have an itch in the Temple of Fame.' Brown drops in. Brown is said by all his friends to be the toady of Jones. The assurance of Jones in a room is the proof that Brown is in the passage. When Jones has the influenza, Brown dutifully catches a cold in the head. Douglas Jerrold to Brown-' Have you heard the rumour that's flying about town?' 'No.' 'Well, they say Jones pays the dog tax for you.' Douglas Jerrold is seriously disappointed with a certain book written by one of his friends, and has expressed his disappointment. Friend-'I have heard you said - was the worst book I ever wrote.' Jerrold-' No, I didn't. I said it was the worst book anybody ever wrote.' A supper of sheep's-heads is proposed, and presently served. One gentleman present is particularly enthusiastic on the excellence of the dish, and, as he throws down his knife and fork, exclaims, 'Well, sheep's-head for over, say I!' Jerrold-'There's egotism!' It is worth while to note the succession of the prime jokers of London before jerrold. The series begins with King Charles II, to whom succeeded the Earl of Dorset, after whom came the Earl of Chesterfield, who left his mantle to George Selwyn, whose successor was a man he detested, Richard Brimisley Sheridan; after whom was Jekyl, then Theodore Hook, whose successor was Jerrold: eight in all during a term of nearly two hundred years. INTRODUCTION OF FEMALE ACTORSPepys relates, in that singular chronicle of gossip, his Diary, under January 3. 1661, that he went to the theatre and saw the Beggar's Bush well performed; 'the first time,' says he, 'that over I saw women come upon the stage.' This was a theatre in Gibbon's Tennis Court, Vere Street, Clare Market, which had been opened at the recent restoration of the monarchy, after the long theatrical blank under the reign of the Puritans. It had heretofore been customary for young men to act the female parts. All Shakespeare's heroines were thus awkwardly enacted for the first sixty years. At length, on the restoration of the stage, it was thought that the public might perhaps endure the indecorum of female acting, and the venture is believed to have been first made at this theatre on the 8th of December 1660, when a lady acted Desdemona for the first time. Colley Cibber gives a comic traditional story regarding the time when this fashion was coming in. 'Though women,' says he, 'were not admitted to the stage till the return of King Charles, yet it could not be so suddenly supplied with them, but that there was still a, necessity, for some time, to put the handsomest young men into petticoats. which Kynaston was said to have then worn with success; particularly in the part of Evadne in the Maid's Tragedy, which I have heard him speak of, and which calls to any mind a ridiculous distress that arose from that sort of shifts which the stage was then put to. The king, coming before his usual time to a tragedy, found the actors not ready to begin; when his Majesty, not choosing to have as much patience as his good subjects, sent to them to know the meaning of it; upon which the master of the company came to the box, and rightly judging that the best excuse for their default would be the true one, fairly told his Majesty that the queen was not shaved yet. The king, whose good humour loved to laugh at a jest as well as make one, accepted the excuse, which served to divert him till the male queen could be efteminated Kynaston was at that time so beautiful a youth, that the ladies of quality prided them-selves in taking him with them in their coaches to Hyde Park in his theatrical habit, after the play, which in those days they might have sufficient time to do, because plays then were used to begin at four o'clock.' THE HORN BOOK In the manuscript account books of the Archer family, quoted by - Mr. Halliwell in his elaborate notes on Shakespeare, occurs this entry: 'Jan.:3, 1715-16, one horn-book for Mr. Eyres, 00: 00: 02.' The article referred to as thus purchased at two-pence was one once most familiar, but now known only as a piece of antiquity, and that rather obscurely. The remark has been very justly made, that many books, at one time enjoying a more than usually great circulation, are precisely those likely to become the scarcest in a succeeding age; for example, nearly all school-books, and, above all, a Horn-Book. Down to the time of George II, there was perhaps no kind of book so largely and universally diffused as this said horn-book; at present, there is perhaps no book of that reign, of which it would be more difficult to procure a copy. The annexed representation is copied from one given by Mr. Halliwell, as taken from a black-letter example which was found some years ago in pulling down an old farm-house at Middleton, in Derbyshire. A portrait of King Charles I in armour on horseback was upon the reverse, affording us an approximation to the date. The horn-book was the Primer of our ancestors -their established means of learning the elements of English literature. It consisted of a single leaf, containing on one side the alphabet large and small-in black-letter or in Roman-with perhaps a small regiment of monosyllables, and a copy of the Lord's Prayer; and this leaf was usually set in a frame of wood, with a slice of diaphanous horn in front - hence the name horn-book. Generally there was a handle to hold it by, and this handle had usually a hole for a string, whereby the apparatus was slung to the girdle of the scholar. In a View of the Beau Monde, 1731, p. 52, a lady is described as 'dressed like a child, in a bodice coat and leading-strings, with a horn-book tied to her side.' A various kind of horn-book gave the leaf simply pasted against a slice of horn; but the one more generally in use was that above described. It is to it that Shenstone alludes in his beautiful cabinet picture-poem, The Schoolmistress, where he tells of the children, how: Their books of stature small they take in hand, Which with pellucid horn secured are, To save from fingers wet the letters fair.' It ought not to be forgotten that the alphabet on the horn-book was invariably prefaced with a Cross: whence it came to be called the Christ Cross Row, or by corruption the Criss Cross Row, a term which was often used instead of horn-book. In earlier times, it is thought that a cast-leaden plate, containing the alphabet in raised letters, was used for the instruction of the youth of England, as Sir George Musgrave of Eden-hall possesses two carved stones which appear to have been moulds for such a production. MIGRATORY BOGSOn a bitter winter's night, when rain had softened the ground, and loosened such soil as was deficient in cohesiveness, a whole mass of Irish bog or peat-moss shifted from its place. It was on the 3rd of January 1853; and the spot was in a wild region called Enagh Monmore. The mass was nearly a mile in circumference, and several feet deep. On it moved, urged apparently by the force of gravity, over sloping ground, and continuing its strange march for twenty-four hours, when a change in the contour of the ground brought it to rest. Its extent of movement averaged about a quarter of a mile. Such phenomena as these, although not frequent in occurrence, are sufficiently numerous to deserve notice. There are in many, if not most countries, patches of ground covered with soft boggy masses, too insecure to build upon, and not very useful in any other way. Bogs, mosses, quagmires, marshes, fens-all have certain points of resemblance: they are all masses of vegetable matter, more or less mixed with earth, and moistened with streams running through them, springs rising beneath them, or rains falling upon them. Some are masses almost as solid as wood, fibrous, and nearly dry; some are liquid black mud; others are soft, green, vegetable, spongy accumulations; while the rest present intermediate characters. Peat-bogs of the hardest kind are believed to be the result of decayed forests, acted upon by long-continued heat, moisture, and pressure; mosses and marshes are probably of more recent formation, and are more thoroughly saturated with water. In most cases they fill hollows in the ground; and if the edges of those hollows are not well-defined and sufficiently elevated, we are very likely to hear of the occurrence of quaking bogs and flow-mosses. In the year 1697, at Charleville, near Limerick, a peat-bog burst its bounds. There was heard for some time underground a noise like thunder at a great distance or when nearly spent. Soon afterwards, the partially-dried crust of a large bog began to move; the convexity of the upper surface began to sink; and boggy matter flowed out at the edges. Not only did the substance of the bog move, but it carried with it the adjacent pasture-grounds, though separated by a large and deep ditch. The motion continued a considerable time, and the surface rose into undulations, but without bursting up or breaking. The pasture-land rose very high, and was urged on with the same motion, till it rested upon a neighbouring meadow, the whole surface of which it covered to a depth of sixteen feet. The site which the bog had occupied was left full of unsightly holes, containing foul water giving forth stinking vapours. It was pretty well ascertained that this catastrophe was occasioned by long-continued rain-not by softening the bog on which it fell, but by getting under it, and so causing it to slide away. England, though it has abundance of fenny or marshy land in the counties lying west and south of the Wash, has very few such bogs as those which cover nearly three million acres of land in Ireland. There are some spots, however, such as Chat moss in Lancashire, which belong to this character. Leland, who wrote in the time of Henry the Eighth, described, in his quaint way, an outflow of this moss: 'Chat Moss brast up within a mile of Mosley Haul, and destroied much grounde with mosse thereabout, and destroyed much fresh-water fishche thereabout, first corrupting with stinkinge water Glasebrooke, and so Glasebrooke carried stinkinge water and mosse into Mersey water, and Mersey corrupted carried the roulling mosse, part to the shores of Wales, part to the isle of Man, and some unto Ireland. And in the very top of Chateley More, where the mosse was hyest and brake, is now a fair plaine valley as ever in tymes paste, and a rylle runnith int, and peaces of small trees be found in the bottom.' Let it be remembered that this is the same Chat Moss over which the daring but yet calculating genius of George Stephenson carried a railway. It is amusing now to look back at the evidence given, thirty-five years ago, before the Parliamentary Committee on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. Engineers of some eminence vehemently denied the possibility of achieving the work. One of them said that no vehicle could stand on the Moss short of the bottom; that the whole must be scooped out, to the depth of thirty or forty feet, and an equivalent of hard earth filled in; and that even if a railway could be formed on the Moss, it would cost £200,000. Nevertheless Stephenson did it, and expended only £30,000; and there is the railway, sound to the present hour. The moss, over an area of nearly twelve square miles, is so soft as to yield to the foot; while some parts of it are a pulpy mass. Stephenson threw down thousands of cubic yards of firm earth, which gradually sank, and solidified sufficiently to form his railway upon; hurdles of heath and brushwood were laid upon the surface, and on these the wooden sleepers. There is still a gentle kind of undulation, as if the railway rested on a semi-fluid mass; nevertheless it is quite secure. Scotland has many more bogs and peat-mosses than England. They are found chiefly in low districts, but sometimes even on the tops of the mountains. Mr. Robert Chambers gives an account of an outburst which took place in 1629: 'In the fertile district between Falkirk and Stirling, there was a large moss with a little lake in the middle of it, occupying a piece of gradually-rising ground. A highly-cultivated district of wheat-land lay below. There had been a series of heavy rains, and the moss became overcharged with moisture. After some days, during which slight movements were visible on this quagmire, the whole mass began one night to leave its native situation, and slide gently down to the low grounds. The people who lived on these lands, receiving sufficient warning, fled and saved their lives; but in the morning light they beheld their little farms, sixteen in number, covered six feet deep with liquid moss, and hopelessly lost.' -Domestic Annals of Scotland, ii. 35. Somewhat akin to this was the flowing moss described by Pennant. It was on the Scottish border, near the shore of the Solway. When he passed the spot during his First Journey to Scotland in 1768, he saw it a smiling valley; on his Second Journey, four years afterwards, it was a dismal waste. The Solway Moss was an expanse of semi-liquid bog covering 1600 acres, and lying somewhat higher than a valley of fertile land near Netherby. So long as the moderately hard crust near the edge was preserved, the moss did not flow over: but on one occasion some peat-diggers imprudently tampered with this crust; and the moss, moistened with very heavy rain, overcame further control. It was on the night of the 17th of November 1771, that a farmer who lived near the Moss was suddenly alarmed by an unusual noise. The crust had given way, and the black deluge was rolling towards his house while he was searching with a lantern for the cause of the noise. When he he caught sight of a small dark stream, he thought it came from his own farm-yard dung hill, which by some strange cause had been set in motion. The truth soon flashed upon him, however. He gave notice to his neighbors with all expedition. Others,' said Pennant, 'received no other advice than what this Stygian tide gave them: some by its noise, many by its entrance into their houses; and I have been assured that some were surprised with it even in their beds. These passed a horrible night, remaining totally ignorant of their fate, and the cause of their calamity, till the morning, when their neighbors with difficulty got them out through the roof.' About 300 acres of bog flowed over 400 acres of land, utterly ruining and even burying the farms, overturning the buildings, filling some of the cottages up to the roof, and suffocating many cattle. The stuff flowed along like thick black paint, studded with lumps of more solid peat; and it filled every nook and crevice in its passage. 'The disaster of a cow was so singular as to deserve mention. She was the only one, out of eight in the same cow-house, that was saved, after having stood sixty hours up to the neck in mud and water. When she was relieved she did not refuse to eat, but would not touch water, nor would even look at it without manifest signs of horror.' The same things are going on around us at the present day. During the heavy rains of August 1861, there was a displacement of Auehingray Moss between Slamannan and Airdrie. A farmer, looking out one morning from his farm-door near the first-named town, saw, to his dismay, about twenty acres of the moss separate from its clay bottom, and float a distance of three quarters of a mile. The sight was wonderful, but the consequences were grievous; for a large surface of potato-ground and of arable land became covered with the offensive visitant. |