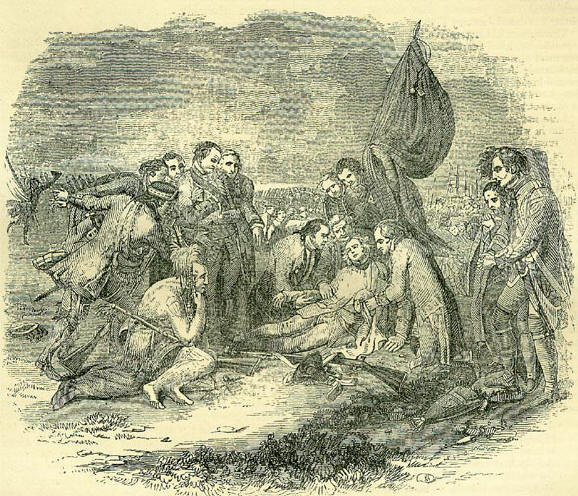

2nd JanuaryBorn: John, Marquis of Granby, 1721; General Wolfe, Westerham, Kent, 1727. Died: Publius Ovidius Naso, the Roman poet, 18; Titus Livius, the Roman historian, 18, Padua; Alexander, Earl of Rosslyn, Lord Chancellor of England, 1805; Dr. John Mason Good, 1827; Dr. Andrew We, chemist, 1857. Feast Day: St. Macarins of Alexandria, anchoret. St. Concordius, martyr. St. Adelard, abbot. [It is not possible in this work to give special notices of all the saints of the Romish calendar; nor is it desirable that such should be done. There are, however, several of them who make a prominent figure in history; some have been remarkable as active and self-devoted missionaries of civilization; while others supply curious examples of the singularities of which men are capable under what are now very generally regarded as morbid views of religion. Of such persons it does not seem improper that notices of a dispassionate nature should be given, among other memorable matters connected with the days of the year.] St. MACARIUSSt. Macarius was a notable example of those early Christians who, for the sake of heavenly meditation, forsook the world and retired to live in savage wildernesses. Originally a confectioner in Alexandria, he withdrew, about the year 325, into the The bais in Upper Egypt, and devoted Himself wholly to religious thoughts. Afterwards, he took up his abode in still remoter deserts, bordering on Lybia, where there were indeed other hermits, but all out of sight of each other he exceeded his neighbours in the practice of those austerities which were then thought the highest qualification for the blessed abodes of the future. 'For seven years together,' says Alban Butler, 'he lived only on raw herbs and pulse, and for the three following years contented himself with four or five ounces of bread a day;' not a fifth part of the diet required to keep the inmates of modern gaols in good health. Hearing great things of the self-denial of the monks of Tabenna, he went there in disguise, and astonished them all by passing through Lent on the aliment furnished by a few green cabbage leaves eaten on Sundays. He it was of whom the striking story is told, that, having once killed a gnat which bit him, he immediately hastened in a penitent and self-mortifying humour to the marshes of Scet'e, which abound with great flies, a torment even to the wild boar, and exposed himself to these ravaging insects for six months; at the end of which time his body was a mass of putrid sores, and he only could be recognised by his voice. The self-devoting, self-denying, self-tormenting anchoret is an eccentricity of human nature now much out of fashion; which, however, we may still contemplate with some degree of interest, for the basis of the character is connected with both true religion and true virtue. We are told of Macarius that he was exposed to many temptations. 'One,' says Butler, 'was a suggestion to quit his desert and go to Rome, to serve the sick in the hospitals; which, by due reflection, he discovered to be a secret artifice of vain-glory inciting him to attract the eyes and esteem of the world. True humility alone could discover the snare which lurked under the specious gloss of holy charity. Finding this enemy extremely importunate, he threw himself on the ground in his cell, and cried out to the fiends, 'Drag me hence, if you can, by force, for I will not stir.' Thus he lay till night, and by this vigorous resistance they were quite disarmed. As soon as he arose they renewed the assault; and he, to stand firm against them, filled two great baskets with sand, and laying them on his shoulders, travelled along the wilderness. A person of his acquaintance meeting him, asked him what he meant, and made an offer of casing him of his burden; but the saint made no other reply than this: 'I am tormenting my tormentor.' He returned home in the evening, much fatigued in body, but freed from the temptation. St. Macarius once saw in a vision, devils closing the eyes of the monks to drowsiness, and tempting them by diverse methods to distractions, during the time of public prayer. Some, as often as they approached, chased them away by a secret supernatural force, whilst others were in dalliance with their suggestions. The saint burst into sighs and tears; and, when prayer was ended, admonished every one of his distractions, and of the snares of the enemy, with an earnest exhortation to employ, in that sacred duty, a more than ordinary watchfulness against his attacks. St. Jerom and others relate, that, a certain anchoret in Nitria having left one hundred crowns at his death, which he had acquired by weaving cloth, the monks of that desert met to deliberate what should be clone with the money. Some were for having it given to the poor, others to the church; but Macarius, Pambo, Isidore, and others, who were called the fathers, ordained that the one hundred crowns should be thrown into the grave and buried with the corpse of the deceased, and that at the same time the following words should be pronounced: May thy money be with thee to perdition. This example struck such a terror into all the monks, that no one durst lay up any money by him.' Butler quotes the definition of an anchoret given by the Abbot Ranee de la Trappe, as a lively portraiture of the great Macarins: 'When,' says he, 'a soul relishes God in solitude, she thinks no more of anything but heaven, and forgets the earth, which has nothing in it that can now please her; she burns with the fire of divine love, and sighs only after God, regarding death as her greatest advantage: nevertheless they will find themselves much mistaken, who, leaving the world, imagine they shall go to God by straight paths, by roads sown with lilies and roses, in which they will have no difficulties to conquer, but that the hand of God will turn aside whatever could raise any in their way, or disturb the tranquillity of their retreat: on the contrary, they must be persuaded that temptations will everywhere follow them, that there is neither state nor place in which they can be exempt, that the peace which God promises is procured amidst tribulations, as the rose buds amidst thorns; God has not promised his servants that they shall not meet with trials, but that with the temptation he will give them grace to be able to hear it: heaven is offered to us on no other conditions; it is a kingdom of conquest ... the prize of victory but, 0 God, what a prize!' GENERAL WOLFEWhen in 1759, Pitt entrusted General Wolfe the expedition against Quebec, on the day preceding his embarkation, Pitt, desirous of giving his last verbal instructions, invited him to dinner at Hayes, Lord Temple being the only other guest. As the evening advanced, Wolfe, healed, perhaps by his own aspiring thoughts, and the unwonted society of statesmen, broke forth in a strain of gasconade and bravado. He drew his sword and rapped the table with it, he Flourished it round the room, and he talked of the mighty things winch that sword was to achieve. The two Ministers sat aghast at an exhibition so unusual from any man of real sense and spirit. And when, at last, Wolfe had taken his leave, and his carriage was heard to roll from the door, Pitt seemed for the moment shaken in the right opinion which his deliberate judgment had formed of Wolfe: he lifted up his eyes and arms, and exclaimed to Lord Temple: 'God God! that, I should have entrusted the fate of the country and of the administration to such hands!' This story as told by Lord Temple himself to the Rt. Hon. Thomas Grenville the friend of Lord Mahon, who has inserted the anecdote in his History of Ragland, vol. iv. Lord Temple also told Mr. Grenville, that on the evening in question, Wolfe had partaken most sparingly of wine, so that this ebullition could not have been the effect of any excess. The incident affords a striking proof how much a fault of manner may obscure and disparage high excellence of mind. Lord Mahon adds: 'It confirms Wolfe's own avowal, that he was not seen to advantage in the common occurrences of life, and shows how shyness may, at intervals, rush, as it were, for refuge, into the opposite extreme; but it should also lead us to view such defects of manner with indulgence, as proving that they may co-exist with the highest ability and the purest virtue.'  The death of General Wolfe was a kind of military martyrdom. He had failed in several attempts against the French power in Canada, dreaded a court martial, and resolved by a bold and original stroke to justify the confidence of Pitt, or die. Thence the singularity of his movement to get upon the plain of Abram behind Quebec. The French came out of their fortress, fought him, and were beaten; but a stray shot brought down the young hero in the moment of victory: The genius of West has depicted very successfully a scene which remains engraved in the national heart. Wolfe died on the 13th of September 1759, in the 33rd year of his age. His body was brought to England, and interred at Greenwich. The want of a life of General Wolfe, a strange want, considering the glory which rests on the name, has caused some points regarding him to remain in doubt. It is doubtful, for example, if he was in service in the campaign of the Duke of Cumberland in the north of Scotland in 1746. In Jacobite Memoirs of the Rebellion of 1745-6, a collection of original papers edited by Mr. Robert Chambers in 1834, there are evidences of a gentleman's house at Aberdeen having been forcibly taken possession of by the Duke of Cumberland and General Hawley; who, not content with leaving no requital behind them, took away many articles of value, which are afterwards found to have been sold in London. In this unpleasant story, a 'Major Wolfe,' described as aide-de-camp to Hawley, figures as a bearer of rough messages. A painful question arises, 'Could this be the future hero of Quebec? 'One fact is gratifying by contradiction, that this hero was not a major till 1749. Could it be his father? This is equally or more unlikely, for he was then a brigadier-general. It is to be observed that James Wolfe, though. only nineteen at this time, was a captain in Barrell's regiment (having received that commission in June 1744), and Barrell's regiment, we know, stood in the left of the front line of the royal army at Culloden: a mistake of major for captain is easily conceivable. In the hope of getting conclusive evidence that the admired Wolfe was not involved in the personal barbarisms of Cumberland and Hawley, the editor of the Jacobite Memoirs wrote to Mr. Southey, who, he understood, was prepared to compile a memoir of General Wolfe from original materials; and he received the following answer: 'Keswick, 11th August, 1833. Sir, Immediately upon receiving your obliging letter, I referred to my own notes and extracts from the correspondence of Wolfe with his family, the whole of which has been in my possession. 'There I find that his father was with the Duke of Cumberland's army in 1745, and that he himself was at Newcastle in the November of that year. His father was a general at that time; and Wolfe, I think, was not yet a major (though I cannot immediately ascertain this), for he only received his lieutenant's commission in June 1744. My present impression is that he was not in the Scotch campaign, and that the Major Wolfe of whom your papers speak must have been some other person. His earliest letter from Scotland is dated January 1749. 'Throughout his letters Wolfe appears to have been a considerate, kind-hearted man, as much distinguished from most of his contemporary officers by humane and gentlemanly feeling as by the zeal with which he devoted himself to his profession. All that has hitherto been known of him tends to confirm this view of his character. 'I am much obliged to you for your offer of the volume in which the paper is printed, and shall thankfully receive it when it is published. Meantime, Sir, I have the honour to remain, &c.' If, after all, there is nothing but character to plead against the conclusion that Wolfe was the harsh message bearer of the brutal Hawley, it is to be feared that the defense is a weak one. In the army which marched into Scotland in 1746, and put down the rebellion, there was a general indignation and contempt for the Scottish nation, disposing men otherwise humane to take very harsh measures. The ordinary laws were trampled on; worthy friends of the government who pleaded for mercy to the vanquished, were treated with contumely; some of the English officers were guilty of extreme cruelty towards the highland peasantry. No one is remembered with more horror for his savage doings than a certain Captain Caroline Scott; and yet this is the same man whom Mallet introduces in his poem of the Wedding Days as a paragon of amiableness. The verses are as follows: A second see! of special note, Phomp Comus in a Colonel's coat; Whom we this day expect from far, A jolly first-rate mean of war; On whom. we boldly dare repose, To meet our friends, or meet our foes. To which the poet appends a prose note: 'The late Col. Caroline Scott, who, though extremely corpulent, was uncommonly active; and who, to much skill, spirit, and bravery, as an officer, joined the greatest gentleness of manners as a companion and friend. He died a sacrifice to the public, in the service of the East India Company, at Bengal, in the year 1755.' If the Caroline Scott who tortured the poor highlanders was really this gentle-natured man, the future hero of Quebec can be imagined as carrying rough messages to the lady at Aberdeen. In the National Portrait Gallery, Westminster, there is a bust portrait of General Wolfe, representing him in profile, and with a boyish cast of countenance. OVIDOvid died at about the age of sixty-one. We have only imperfect accounts of the Roman bards; but we know pretty clearly that Ovid lived as a gay and luxurious gentleman in Rome through the greater part of the reign of Augustus, and when past fifty was banished by that emperor, probably in consequence of his concern in some scandalous amour of a female member of the imperial family. Let us think of what; it would be for a darling of London society like the late Thomas Moore to have been condemned to spend his days at a fishing-village in Friesland or Lapland, and we shall have some idea of the pangs of the unforunate Naso on taking up his forced abode at Tomi on the Black Sea. His epistles thence are full of complaints of the severity of the climate, the wildness of the scenery, and the savage nature of the surrounding people. How much we find expressed in that well-known line addressed to a book which he sent from Tomi to be published in Rome:--' Sine me, liber, ibis in urbem!' Yet it appears that the inhabitants appreciated his literary reputation, and treated him with due respect; also that he tried to accommodate himself to his new circumstances by learning their language. Death brought the only true relief which he could experience, after he had endured this exile at least eight years. It is an interesting instance of the respect which brilliant talents extort even from the rudest, that a local monument was reared to Ovid, and that Tomi is now called Ovidiopol, or Ovid's City. 'I have a veneration for Virgil,' says Dr. King; I admire Horace; but I love Ovid. . . Neither of these great poets knew how to move the passions so well as Ovid; witness some of the tales of his Metamorphoses, particularly the story of Ceyx and Haleyone, which I never read without weeping. No judicious critic: hath ever yet denied that Ovid has more wit than any other poet of the Augustan age. That the has too much, and that his fancy is too luxuriant, is time fault generally imputed to him. All the imperfection of Ovid are really pleasing. But who would not excuse all his faults on account of his many excellencies, particularly his descriptions, which have never been equaled.' LORD CHANCELLOR ROSSLYNAlexander Wedderburn, Earl of Rosslyn, Lord Chancellor of England from 1793 to 1801, entered in his youth at the Scottish bar, but had from the first an inclination to try the English, as a higher field of ambition. After going through the usual drudgeries of a young Scotch counsel for three years, he was determined into that career which ended in the English chancellorship by an accident. There flourished at that time at the northern bar a veteran advocate named Lockhart, the Dean of the body, realizing the highest income that had ever been known there, namely, a thousand a year, and only prevented from attaining the bench through the mean spite of the government, in consequence of his having gallantly gone to defend the otherwise helpless Scotch rebels at Carlisle in 1746. Lockhart, with many merits, wanted that of a pleasant temper. He was habitually harsh and overbearing towards his juniors, four of whom (including Wedderburn) at length agreed that, on the first occasion of his shewing any insolence towards one of them, he should publicly insult him, for which object it was highly convenient that the Dean had been once threatened with a caning, and that his wife did not bear a perfectly pure character. In the summer of 1757, Wedderburn chanced to be opposed to Lockhart, who, nettled probably by the cogency of his arguments, hesitated not to apply to him the appellation of 'a presumptuous boy.' The young advocate, rising afterwards to reply, poured out upon Lockhart a torrent of invective such as no one in that place had ever heard before. 'The learned Dean,' said he, has confined himself on this occasion to vituperation; I do not say that he is capable of reasoning, but if tears would have answered his purpose, I am sure tears would not have been wanting.' Lockhart started up and threatened him with vengeance. 'I care little, my lords,' said Wedderburn, 'for what may be said or done by a man who has been disgraced in his person and dishonoured in his bed.' The judges felt their flesh creep at the words, and Lord President Craigie could with difficulty summon energy to tell the young pleader that this was language unbecoming an advocate and unbecoming a gentleman. According to Lord Campbell, 'Wedderburn, now in a state of such excitement as to have lost all sense of decorum and propriety, exclaimed that 'his lordship had said as a judge what he could not justify as a gentleman.' The President appealed to his brethren as to what was fit to be clone, who unanimously resolved that Mr. Wedderburn should retract his words and make an humble apology, on pain of deprivation. All of a sudden Wedderburn seemed to have subdued his passion, and put on an air of deliberate coolness; when, instead of the expected retractation and apology, he stripped off his gown, and holding it in his hands before the judges, he said: 'My lords, I neither retract nor apologise, but I will save you the trouble of deprivation; there is my gown, and I will never wear it more; virtute me involvo.' He then coolly laid his gown upon the bar, made a low bow to the judges, and, before they had recovered from their amazement, he left the court, which he never again entered.' It is said that he started that very day for London, where, thirty-six years afterwards, he attained the highest place which it is in the power of a barrister to reach. It is generally stated that he never revisited his native country till near the close of his life, after his resignation of the chancellorship. There is something spirited, and which one admires and sympathises with, in the fact of a retort and reproof administered by a young barrister to an elderly one presuming upon his acquired reputation to be insolent and oppressive; but the violence of Wedderburn's language cannot be justified, and such merit as there was in the case one would have wished to see in connection with a name more noted for the social virtues, and less for a selfish ambition, than that of Alexander Wedderburn. CAPTURE OF GRANADA, 1492The long resistance of the Moors to the Spanish troops of King Ferdinand and Isabella being at length overcome, arrangements were made for the surrender of their capital to the Spaniards. As the Bishop of Avila passed in to take possession of the Alhambra the magnificent palace of the Moorish king its former master mournfully passed out, saying only, 'Go in, and occupy the fortress which Allah has bestowed upon your powerful land, in punishment of the sins of the Moors!' The Catholic sovereigns meanwhile waited in the vega below, to see the silver cross mounted on the tower of the Alhambra, the appointed symbol of possession. As it appeared, a shout of joy rose from the assembled troops, and the choristers of the royal chapel broke forth with the anthem, Te Deum laudamus. Boabdil, king of the Moors, accompanied by about fifty horsemen, here met the Spanish sovereigns, who generously refused to allow him to pay any outward homage to them, and delivered up to him, with expressions of kindness, his son who had been for some time in their hands as a hostage. Boabdil handed them the keys of the city, saying, 'Thine, 0 king, are our trophies, our kingdom, and our person; such is the will of God!' After some further conversation, the Moorish king passed on in gloomy silence, to avoid witnessing the entrance of the Spaniards into the city. Coming at about two leagues' distance to an elevated point, from which the last view of Granada was to be obtained, he could not restrain himself from turning round to take a parting look of that beautiful city which was lost to him and his for ever. 'God is great!' was all he could say; but a flood of tears burst from his eyes. His mother upbraided him for his softness; but his vizier endeavored to console him by remarking that even great misfortunes served to confer a certain distinction. 'Allah Achbar!' said He; 'when did misfortunes ever equal mine?' 'From this circumstance,' says Mr. Irving, in his Chronicle of the Conquest of Granada, 'the hill, which is not far from Padul, took the name of Fez Allah Achbar; but the point of view commanding the last prospect of Granada is known among Spaniards by the name of El ultimo suspiro del Moro, or the Last Sigh of the Moor.' EXECUTION OF JOHN OF LEYDEN, 'THE PROPHET' 1536It was in 1523 that the sect of the Anabaptists rose in Germany, so named because they wished that people should re-baptize their children, so as to imitate Jesus Christ, who had been baptized when grown up. Two fanatics named Storck and Muncer were the leaders of this sect, the most horrible that had ever desolated Germany. As Luther had raised princes, lords, and magistrates against the Pope and the bishops, Muncer raised the peasants against the princes, lords, and magistrates. He and his disciples addressed themselves to the inhabitants of Swabia, Misnia, Thuringia, and Franconia, preaching to them the doctrine of an equality of conditions among men. Germany became the theatre of bloody doings. The peasantry rose in Saxony, even as far as Alsace; they massacred all the gentlemen they met, including in the slaughter a daughter of the Emperor Maximilian I; they ravaged every district to which they penetrated; and it was not till after they had carried on these frightful proceedings for three years, that the regular troops got the better of them. Muncer, who had aimed at being a second Mahomet, perished on the scaffold at Mulhausen. The chiefs, however, did not perish with him. The peasants were raised anew, and acquiring additional strength in Westphalia, they made themselves masters of the city of Munster, the bishop of which fled at their approach. They here endeavoured to establish a theocracy like that of the Jews, to be governed by God alone; but one named Matthew their principal prophet being killed, a tailor lad, called John of Leyden, assured them that God had appeared to him and named him king; and what he said the people believed. The pomp of his coronation was magnificent. One can yet see the money which he struck; he took as his armorial bearings two swords placed the same way as the keys of the Pope. Monarch and prophet in one, he sent forth twelve apostles to announce his reign throughout all Low Germany. After the example of the Hebrew sovereigns, he wished to have a number of wives, and he espoused twelve at one time. One having spoken disrespectfully of him, he cut off her head in the presence of the rest, who, whether from fear or fanaticism, danced with him round the dead body of their companion. This prophet-king had one virtue courage. He defended Munster against its bishop with unfaltering resolution during a whole year. Notwithstanding the extremities to which he was reduced, he refused all offers of accommodation. At length he was taken, with arms in his hands, through treason among his own people; and the bishop, after causing him to be carried about for some time from place to place as a monster, consigned him to the death reserved for all kings of his order. EXTRAORDINARY LIGHTOn the 2nd of January 1756, at four in the afternoon, at Tuam, in Ireland, an unusual light, far above that of the brightest day, struck all the beholders with amazement. It then faded away by invisible degrees; but at seven, from west to east, 'a sun of streamers' appeared across the sky, undulating like the waters of a rippling stream. A general feeling of alarm was excited by this singular phenomenon. The streamers gradually became discoloured, and flashed away to the north, attended by a shock, which all felt, but which did no damage. Gentleman's Magazine, xxvi. 39. The affair seems to have been an example of the aurora borealis, only singular in its being bright enough to tell upon the daylight. UNFOUNDED BUT DESERVING POPULAR NOTIONSUnder this head may be ranked a belief amongst book-collectors, that certain books of uncommon elegance were, by a peculiar dilettanteism of the typographer, printed from silver types. In reality, types of silver would not print a book more elegantly than types of the usual composite metal. The absurdity of the idea is also shewn by the circumstances under which books are for the most part composed; some one has asked, very pertinently, if a set of thirsty compositors would not have quickly discovered 'how many ems, long primer, would purchase a gallon of beer.' It is surmised that the notion took its rise in a mistake of silver for Elzevir type, such being the term applied early in the last century to types of a small size, similar to those which had been used in the celebrated miniature editions of the Amsterdam printers, the Elzevirs. Another of these popular notions has a respectability about it, because, though not true, it proceeds on a conception of what is just and fitting. It represents all persons who have ever had anything to do with the invention or improvement of instruments of death, as suffering by them, generally as the first to suffer by them. Many cases are cited, but on strict examination scarcely one would be found to be true. It has been asserted, for example, that Dr. Guillotine of Paris, who caused the introduction into France of the instrument bearing his name, was himself the first of its many victims; whereas he in reality outlived the Revolution, and died peaceably in 1814. Nor is it irrelevant to keep in mind regarding Guillotine, that he was a man of gentle and amiable character, and proposed this instrument for execution as calculated to lessen the sufferings of criminals. So has it been said that the Regent Morton of Scotland introduced the similar instrument called the Maiden into his country, having adopted it from an instrument for beheading which long stood in terror of the wicked at one of the gates of the town of Halifax in Yorkshire. But it is ascertained that, whether Morton introduced it or not and there is no proof that he did--it was in operation at Edinburgh some years before his death; first under the name of the Maiden, and afterwards under that of the Widow a change of appellation to which it would be entitled after the death of its first bridegroom. It has likewise been represented that the drop used in hanging was an improvement effected by an eminent joiner and town-councillor of Edinburgh, the famous Deacon Brodie, and that when he was hanged in October 1788 for housebreaking, he was the first to put the utility of the plan to the proof. But it is quite certain that, whether Brodie made this improvement or not, he was not the first person to test its serviceableness, as it appears to have been in operation at least three years before his death. Even his title to the improvement must be denied, except, perhaps, as far as regards the introduction of it into practice in Edinburgh, as some such contrivance was used at the execution of Earl Ferrers in 1760, being part of a scaffold which the family of the unfortunate nobleman caused their under-taker to prepare on that occasion, that his lord-ship might not swing off from a cart like a plebeian culprit. 'There was,' says Horace Walpole, 'a new contrivance for sinking the stage under him, which did not play well; and he suffered a little by the delay, but was dead in four minutes.' It is much to be feared that there is no belief of any kind more extensively diffused in England, or more heartily entertained, than that which represents a Queen Anne's farthing as the greatest and most valuable of rarities. The story everywhere told and accepted is, that only three far-things were struck in her reign: that two are in public keeping; and that the third is still going about, and if it could be recovered would bring a prodigious price. In point of fact, there were eight comings of farthings in the reign of Queen Anne, besides a medal or token of similar size, and these coins are no greater rarities than any other precinct of the Mint issued a hundred and fifty years ago. Every now and then a poor person comes up from a remote place in the country to London, to sell the Queen Anne's farthing, of which he has become the fortunate possessor; and great, of course, is the disappointment when the numismatist offers him perhaps a shilling for the curiosity, justifying the lowness of the price by pulling out a drawer and shewing him eight or ten other examples of the same coin. On one occasion, a labourer and his wife came all the way from Yorkshire on foot to dispose of one of these provoking coins in the metropolis. It is related that a rural publican, having obtained one of the tokens, put it up in his window as a curiosity, and people came from far and near to see it, doubtless not a little to the alleviation of his beer barrels; nor did a statement of its real value by a numismatist, who happened to come to his house, induce him to put it away. About 1814, a confectioner's shopman in Dublin, having taken a Queen Anne's farthing, substituted an ordinary farthing for it in his master's till, and endeavoured to make a good thing for himself by selling it to the best advantage. The master, hearing of the transaction, had the man apprehended and tried in the Recorder's Court, when he was actually condemned to a twelvemonth's imprisonment for the offence. Numismatists have set forth, as a possible reason for the universal belief in the rarity of Queen Anne's farthings, that there are several pattern-pieces of farthings of her reign in silver, and of beautiful execution, by Croker, which are rare and in request. But it is very unlikely that the appreciation of such an article amongst men of virtue would ever impress the bulk of the people in such a manner or to such results. A more plausible story is, that a lady in the north of England, having lost a Queen Anne's farthing or pattern-piece, which she valued as a keepsake, advertised a reward for its recovery. In that case, the popular imagination would easily devise the remainder of the tale. UNLUCKY DAYSThat peculiar phase of superstition which has regard to lucky or unlucky, good or evil days, is to be found in all ages and climes, wherever the mystery-man of a tribe, or the sacerdotal caste of a nation, has acquired rule or authority over the minds of the people. All over the East, among the populations of antiquity, arc to be found traces of this almost universal worship of luck. It is one form of that culture of the beneficent and the maleficent principles, which marks the belief in good and evil, as an antagonistic duality of gods. From ancient Egypt the evil or unlucky days have received the name of 'Egyptian days.' Nor is it only in pagan, but in Christian times, that this superstition has held its potent sway. No season of year, no month, no week, is free from those untoward days on which it is dangerous, if not fatal, to begin any enterprise, work, or travel. They begin with New-Year's Day, and they only end with the last day of December. Passing over the heathen augurs, who predicted fortunate days for sacrifice or trade, wedding or war, let us see what our Anglo-Saxon forefathers believed in this matter of days. A Saxon MS. (Cott. MS. Vitell, C. viii. fo. 20) gives the following account of these Dies Mali - 'Three days there are in the year, which we call Egyptian days; that is, in our language, dangerous days, on any occasion whatever, to the blood of man or beast. In the month which we call April, the last Monday; and then is the second, at the coming in of the month we call August; then is the third, which is the first Monday of the going out of the month of December. He who on these three days reduces blood, be it of man, be it of beast, this we have heard say, that speedily on the first or seventh day, his life he will end. Or if his life be longer, so that he come not to the seventh day, or if he drink some time in these three days, he will end his life; and he that tastes of goose-flesh, within forty days' space his life he will end.' In the ancient Exeter Kalendar, a MS. said to be of the age of Henry II, the first or Kalends of January is set down as 'Dies Mala.' These Saxon Kalendars give us a total of about 24 evil days in the 365; or about one such in every fifteen. But the superstition 'lengthened its cords and strengthened its stakes; 'it seems to have been felt or feared that the black days had but too small a hold on their regarders; so they were multiplied. 'Astronomers say that six days of the year are perilous of death; and therefore they forbid men to let blood on them, or take any drink; that is to say, January 3rd, July 1st, October 2nd, the last of April, August 1st, the last day going out of December. These six days with great diligence ought to be kept, but namely [mainly?] the latter three, for all the veins are then full. For then, whether man or beast be knit in them within 7 days, or certainly within 14 days, he shall die. And if they take any drinks within 15 days, they shall die; and if they eat any goose in these 3 days, within 40 days they shall die; and if any child be born in these 3 latter days, they shall die a wicked death. Astronomers and astrologers say that in the beginning of March, the seventh night, or the fourteenth day, let the blood of the right arm; and iii the beginning of April, the 11th day, of the left arm; and in the end of May, 3rd or 5th (lay, on whether arm thou wilt; and thus, of all the year, thou shalt orderly be kept from the fever, the falling gout, the sister gout, and loss of thy sight.' Book of Knowledge, b. 1. p. 19. Those who may be inclined to pursue this subject more fully, will find an essay on 'Day-Fatality,' in John. Aubrey's Miscellanies, in which he notes the days lucky and unlucky, of the Jews, Greeks, Romans, and of various distinguished individuals of later times. In a comparatively modern MS. Kalendar, of the time of Henry VI, in the writer's possession, one page of vellum is filled with the following, of which we modernise the spelling: These underwritten be the perilous day's, for to take any sickness in, or to be hurt in, or to be wedded in, or to take any journey upon, or to begin any work on, that he would well speed. The number of these days be in the year 32; they be these: The copyist of this dread list of evil days, while apparently giving the superstition a qualified credence, manifests a higher and nobler faith, lifting his aspiration above days and seasons; for he has appended to the catalogue, in a bold firm hand of the time 'Sed tamen in Domino confide.' (But, notwithstanding, I will trust in the Lord.) Neither in this Kalendar, nor in another of the same owner, prefixed to a small MS. volume containing a copy of Magna Charta, &c., is there inserted in the body of the Kalendar anything to denote a 'Dies Mala.' After the Reformation, the old evil days appear to have abated much of the ancient malevolent influences, and to have left behind them only a general superstition against fishermen setting out to fish, or seamen to take a voyage, or landsmen a journey, or domestic servants to enter on a new place--on a Friday. In many country districts, especially in the north of England, no weddings take place on Friday, from this cause. According to a rhyming proverb, 'Friday's moon, come when it will, comes too soon.' Sir Thomas Overbury, in his charming sketch of a milkmaid, says. 'Her dreams are so chaste, that she dare tell them; only a Friday's dream is all her superstition; and she consents for fear of anger.' Erasmus dwells on the 'extraordinary inconsistency' of the English of his day, in eating flesh in Lent, yet holding it a heinous offence to eat any on a Friday out of Lent. The Friday superstitions cannot be wholly explained by the fact that it was ordained to be hold as a fast by the Christians of Rome. Some portion of its maleficent character is probably clue to the character of the Scandinavian Venus Freya, the wife of Odin, and goddess of fecundity But we are met on the other hand by the fact that amongst the Brahmins of India a like superstitious aversion to Friday prevails. They say that 'on this day no business must be commenced.' And herein is the fate foreshadowed of any antiquary who seeks to trace one of our still lingering superstitions to its source. Like the bewildered traveller at the cross roads, he knows not which to take. One leads him into the ancient Teuton forests; a second amongst the wilds of Scandinavia; a third to papal, and thence to pagan Rome; and a fourth carries him to the far east, and there he is left with the conviction that much of what is old and quaint and strange among its, of the superstitious relics of our fore-elders, has its root deep in the soil of one of the ancient homes of the race. |