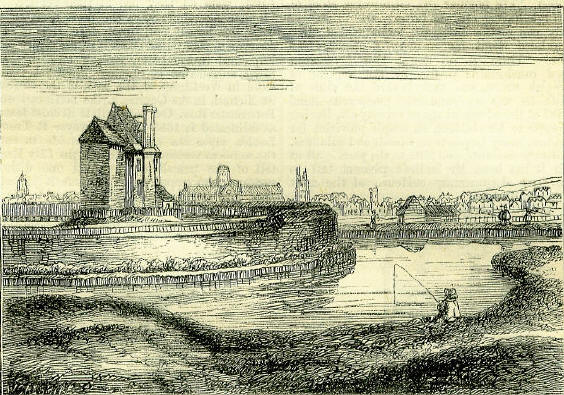

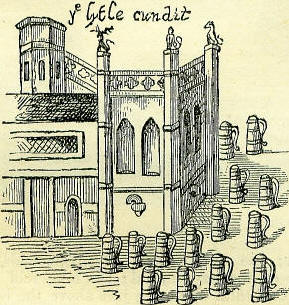

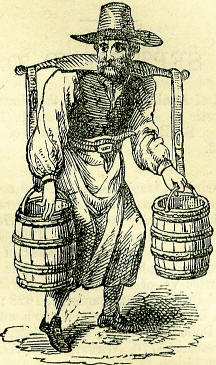

29th SeptemberBorn: John Tillotson, archbishop of Canterbury, 1630, Sowerby, Yorkshire; Thomas Chubb, freethinking author, 1679, East Harnham, Wilts; Robert, Lord Clive, founder of the British empire in India, 1725, Styche, Shropshire; William Julius Mickle, translator of Camaens's Lusiad, 1734, Langholm, Scotland; Admiral Horatio Nelson, naval hero, 1758, Burnham-Thorpe, Norfolk. Died: Pompey the Great, killed in Egypt 48 B. c.; Gustavus Vasa, king of Sweden, 1560, Stockholm; Conrad Vorstins, German divine, 1622, Toningen, Holstein; Lady Rachel Russell, heroic wife of William, Lord Russell, 1723, Southampton House; Charles Franqois Dupuis, astronomer and author, 1809, Is-sur-Til Feast Day: St. Michael and all the Holy Angels. St. Theodota, martyr, 642. MICHAELMAS DAYMichaelmas Day, the 29th of September, properly named the day of St. Michael and All Angels, is a great festival of the Church of Rome, and also observed as a feast by the Church of England. In England, it is one of the four quarterly terms, or quarter-days, on which rents are paid, and in that and other divisions of the United Kingdom, as well as perhaps in other countries, it is the day on which burgal magistracies and councils are re-elected. The only other remarkable thing connected with the day is a widely prevalent custom of marking it with a goose at dinner. Michael is regarded in the Christian world as the chief of angels, or archangel. His history is obscure. In Scripture, he is mentioned five times, and always in a warlike character; namely, thrice by Daniel as fighting for the Jewish church against Persia; once by St. Jude as fighting With the devil about the body of Moses; and once by St. John as fighting at the head of his angelic troops against the dragon and his host. Probably, on the hint thus given by St. John the Romish church taught at an early period that Michael was employed, in command of the loyal angels of God, to overthrow and consign to the pit of perdition Lucifer and his rebellious associates-a legend which was at length embalmed in the sublimest poetry by Milton. Sometimes Michael is represented as the sole arch-angel, sometimes as only the head of a fraternity of archangels, which includes likewise Gabriel, Raphael, and some others. He is usually represented in coat-armour, with a glory round his head, and a dart in his hand, trampling on the fallen Lucifer. He has even been furnished, like the human warriors of the middle ages, with a heraldic ensign-namely, a banner hanging from a cross. We obtain a curious idea of the religious notions of those ages, when we learn that the red velvet-covered buckler worn by Michael in his war with Lucifer used to be shewn in a church in Normandy down to 1607, when the bishop of Avranches at length forbade its being any longer exhibited. Angels are held by the Church of Rome as capable of interceding for men; wherefore it is that prayers are addressed to them and a festival appointed in their honour. Wheatley, an expositor of the Book of Common Prayer, probably expresses the limited view of the subject which is entertained in the Church of England, when he says, that 'I the feast of St. Michael and All Angels is observed that the people may know what blessings are derived from the ministry of angels.' Amongst Catholics, Michael, or, as he has been named, St. Michael, is invoked as 'a most glorious and warlike prince,' chief officer of paradise,' I captain of God's hosts,' receiver of souls,' 'the vanquisher of evil spirits,' and 'the admirable general.' It may also be remarked, that in the Sarum missal, there is a mass to St. Raphael, as the protector of pilgrims and travellers, and a skilful worker with medicine; likewise an office for the continual intercession of St. Gabriel and all the heavenly militia. Protestant writers trace a connection between the ancient notion of tutelar genii and the Catholic doctrine respecting angels, the one being, they say, ingrafted on the other. As to the soundness of this view we do not give any opinion, but it seems certain that in early ages there was a prevalent notion that the affairs of men were much under the direction of angels, good and bad, and men prayed to angels both to obtain good and to avoid evil. Every human being was supposed to have one of these spiritual existences watching over him, aiming at his good, and ready to hear his call when he was in affliction. And, however we may judge this to be a delusion, we must certainly own that, as establishing a connection between the children of earth and something above and beyond the earth, as leading men's minds away from the grossness of worldly pursuits and feelings into the regions of the beautiful and the infinite, it is one of by no means the worst tendency. We must be prepared, however, to find simplicity amidst all the more aspiring ideas of our forefathers. In time, the sainted spirits of pious persons came to stand in the place of the generally name-less angels, and each place and person had one of these as a special guardian and protector. Not only had each country its particular patron or tutelar saint, but there was one for almost every town and church. Even trades and corporations had their special saints. And there was one more specially to be invoked for each particular ail that could afflict humanity. It will be curious here to descend a little into particulars. First, as to countries, England had St. George; Scotland, St. Andrew; Ireland, St. Patrick; Wales, St. David; France, St. Dennis and (in a less degree) St. Michael; Spain, St. James (Jago); Portugal, St. Sebastian; Italy, St. Anthony; Sardinia, St. Mary; Switzerland, St. Gall and the Virgin Mary; Germany, St. Martin, St. Boniface, and St. George Cataphractus; Hungary, St. Mary of Aquisgrana and St. Lewis; Bohemia, St. Winceslaus; Austria, St. Colman and St. Leopold; Flanders, St. Peter; Holland, St. Mary; Denmark, St. Anscharius and St. Canute; Sweden, St. Anscharius, St. Eric, and St. John; Norway, St. Olaus and St. Anscharius; Poland, St. Stanislaus and St. Hederiga; Prussia, St. Andrew and St. Albert; Russia, St. Nicholas, St. Mary, and St. Andrew. Then as to cities, Edinburgh had St. Giles, Aberdeen St. Nicholas, and Glasgow St. Mungo; Oxford had St. Frideswide; Paris, St. Genevieve; Rome, Feast Day: St. Peter and St. Paul; Venice, St. Mark; Naples, St. Januarius and St. Thomas Aquinas; Lisbon, St. Vincent; Brussels, St. Mary and St. Gudula; Vienna, St. Stephen; Cologne, the three kings, with St. Ursula and the eleven thousand virgins. St. Agatha presides over nurses. St. Catherine and St. Gregory are the patrons of literati and studious persons; St. Catherine also presides over the arts. St. Christopher and St. Nicholas preside over mariners. St. Cecilia is the patroness of musicians. St. Cosmas and St. Damian are the patrons of physicians and surgeons, also of philosophers. St. Dismas and St. Nicholas preside over thieves; St. Eustace and St. Hubert over hunters; St. Felicitas over young children. St. Julian is the patron of pilgrims. St. Leonard and St. Barbara protect captives. St. Luke is the patron of painters. St. Martin and St. Urban preside over tipsy people, to save them from falling into the kennel. Fools have a tutelar saint in St. Mathurin, archers in St. Sebastian, divines in St. Thomas, and lovers in St. Valentine. St. Thomas Becket presided over blind men, eunuchs, and sinners, St. Winifred over virgins, and St. Yves over lawyers and civilians. St. Æthelbert and St. Elian were invoked against thieves. Generally, the connection of these saints with the classes of persons enumerated took its rise in some incident of their lives, and in the manner of their deaths; for instance, St. Nicholas was once in danger at sea, and St. Sebastian was killed by arrows. Probably, for like reasons, St. Agatha presided over valleys, St. Anne over riches, St. Barbara over hills, and St. Florian over fire; while St. Silvester protected wood, St. Urban wine and vineyards, and St. Osyth was invoked by women to guard their keys, and St. Anne as the restorer of lost things. Generally, the patron-saints of trades were, on similar grounds, persons who had themselves exercised them, or were supposed to have done so. Thus, St. Joseph naturally presided over carpenters, St. Peter over fishmongers, and St. Crispin over shoemakers. St. Arnold was the patron of millers, St. Clement of tanners, St. Eloy of smiths, St. Goodman of tailors, St. Florian of mercers, St. John Port-Latin of booksellers, St. Louis of periwig-makers, St. Severus of fullers, St. Wilfred of bakers, St. William of hatters, and St. Windeline of shepherds. The name of St. Cloud obviously made him the patron-saint of nailsmiths; St. Sebastian became that of pinmakers, from his having been stuck over with arrows; and St. Anthony necessarily was adopted by swine-herds, in consequence of the legend about his pigs. It is not easy, however, to see how St. Nicholas came to be the presiding genius of parish-clerks, or how the innocent and useful fraternity of potters obtained so alarming a saint as 'St. Gore with a pot in his hand, and the devil on his shoulder.' The medicating saints are enumerated in the following passage from a whimsical satire of the sixteenth century: To every saint they also do his office here assign, And fourteen do they count, of whom thou may'st have aid divine; Among the which Our Lady still cloth hold the chiefest place, And of her gentle nature helps in every kind of case. St. Barbara looks that none without the body of Christ oth die; St. Cath'rine favours learned men and gives them wisdom high, And teacheth to resolve the doubts, and always giveth aid Unto the scolding sophister, to make his reason staid. St. Apolin the rotten teeth doth help when sore they ache; Otilia from the bleared eyes the cause and grief cloth take; Rooke healeth scabs and mangins, with pocks, and scurf, and scall, And cooleth raging carbuncles, and boils, and botches all. There is a saint, whose name in verse cannot declared be, He serves against the plague and each infective malady. St. Valentine, beside, to such as do his power despise The falling-sickness sends, and helps the man that to him cries. The raging mind of furious folk oth Vitus pacify, And oth restore them to their wit, being called on speedily. Erasmus heals the colic and the griping of the guts, And Laurence from the back and from the shoulder sickness puts. Blaise drives away the quinsy quite with water sanctified, From every Christian creature here, and every beast beside. But Leonard of the prisoners oth the bands asunder pull, And breaks the prison-doors and chains, wherewith his church is full. The quartan ague, and the rest cloth Pernel take away, And John preserves the worshippers from prison every day; Which force to Bennet eke they give, that help enough may be, By saints in every place. What dost thou omitted see? From dreadful unprovided death oth Mark deliver his, Who of more force than death himself, and more of value is. St. Anne gives wealth and living great to such as love her most, And is a perfect finder out of things that have been lost; Which virtue likewise they ascribe unto another man, St. Vincent; what he is I cannot tell, nor whence he came. Against reproach and infamy on Susan do they call; Romanus driveth sprites away and wicked devils all. The bishop Wolfgang heals the gout, St. Wendlin keeps the sheep, With shepherds and the oxen fat, as he was wont to keep. The bristled hogs cloth Anthony preserve and cherish well, Who in his lifetime always did in woods and forests dwell. St. Gertrude rids the house of mice, and killeth all the rats; And like doth Bishop Huldrick with his two earth-passing cats. St. Gregory looks to little boys, to teach their a, b, c, And makes them for to love their books, and scholars good to be. St. Nicholas keeps the mariners from dangers and disease, That beaten are with boisterous waves, and toss'd in dreadful seas. Great Christopher that painted is with body big and tall, Doth even the same, who doth preserve and keep his servants all From fearful terrors of the night, and makes them well to most, By whom they also all their life with diverse joys are blest. St. Agatha defends the house from fire and fearful flame, But when it burns, in armour all doth Florian quench the same. It will be learned, with some surprise, that these notions of presiding angels and saints are what have led to the custom of choosing magistracies on the 29th of September. The history of the middle ages is full of curious illogical relations, and this is one of them. Local rulers were esteemed as in some respects analogous to tutelar angels, in as far as they presided over and protected the people. It was therefore thought proper to choose them on the day of St. Michael and All Angels. The idea must have been extensively prevalent, for the custom of electing magistrates on this day is very extensive, September, when by custom (right divine) Geese are ordained to bleed at Michael's shrine says Churchill. This is also an ancient practice, and still generally kept up, as the appearance of the stage-coaches on their way to large towns at this season of the year amply testifies. In Blount's Tenures, it is noted in the tenth year of Edward IV, that John de la Hay was bound to pay to William Barnaby, Lord of Lastres, in the county of Hereford, for a parcel of the demesne lands, one goose fit for the lord's dinner, on the feast of St. Michael the archangel. Queen Elizabeth is said to have been eating her Michaelmas goose when she received the joyful tidings of the defeat of the Spanish Armada. The custom appears to have originated in a practice among the rural tenantry of bringing a good stubble goose at Michaelmas to the landlord, when paying their rent, with a view to making him lenient. In the poems of George Gascoigne, 1575, is the following passage: And when the tenants come to pay their quarter's rent, They bring some fowl at Midsummer, a dish of fish in Lent, At Christmas a capon, at Michaelmas a goose, And somewhat else at New-year's tide, for fear their lease fly loose. We may suppose that the selection of a goose for a present to the landlord at Michaelmas would be ruled by the bird being then at its perfection, in consequence of the benefit derived from stubble-feeding. It is easy to see how a general custom of having a goose for dinner on Michaelmas Day might arise from the multitude of these presents, as land-lords would of course, in most cases, have a few to spare for their friends. It seems at length to have become a superstition, that eating of goose at Michaelmas insured easy circumstances for the ensuing year. In the British Apollo, 1709, the following piece of dialogue occurs: Q: Yet my wife would persuade me (as I am a sinner) To have a fat goose on St. Michael for dinner: And then all the year round, I pray you would mind it, I shall not want money-oh, grant I may find it! Now several there are that believe this is true, Yet the reason of this is desired from you. A: We think you're so far from the having of more, That the price of the goose you have less than before: The custom came up from the tenants presenting Their landlords with geese, to incline their relenting On following payments, &c. Michaelmas Day, 1613, is remarkable in the annals of London, as the day when the citizens assembled to witness, and celebrate by a public pageant, the entrance of the New River waters to the metropolis. SIR HUGH MYDDELTON AND THE WATER SUPPLY OF OLD LONDONThere were present Sir John Swinnerton the lord mayor, Sir Henry Montague the recorder, and many of the aldermen and citizens; and a speech was written by Thomas Middleton the dramatist, who had before been employed by the citizens to design pageants and write speeches for their Lord Mayors' Shows, and other public celebrations. On this occasion, as we are told in the pamphlet descriptive of the day's proceedings, 'warlike music of drums and trumpets liberally beat the air' at the approach of the civic magnates; then 'a troop of labourers, to the number of threescore or up-wards, all in green caps alike, bearing in their hands the symbols of their several employments in so great a business, with drums before them, marching twice or thrice about the cistern, orderly present themselves before the mount, and after their obeisance, the speech is pronounced.' It thus commences: Long have we labour'd, long desir'd, and pray'd For this great work's perfection; and by the aid Of heaven and good men's wishes, 'tis at length Happily conquer'd, by cost, art, and strength: After five years' dear expense in days, Travail, and pains, beside the infinite ways Of malice, envy, false suggestions, Able to daunt the spirit of mighty ones In wealth and courage, this, a work so rare, Only by one man's industry, cost, and care, Is brought to blest effect, so much withstood, His only aim the city's general good. A similar series of mere rhymes details the construction of the works, and enumerates the labourers, concluding thus: Now for the fruits then: flow forth, precious spring, So long and dearly sought for, and now bring Comfort to all that love thee: loudly sing, And with thy crystal murmur struck together, Bid all thy true well-wishers welcome hither! 'At which words,' we are told, 'the flood-gate opens, the stream let into the cistern, drums and trumpets giving it triumphant welcomes,' a peal of small cannon concluding all. This important work, of the utmost sanitary value to London, was commenced and completed by the indomitable energy of one individual, after it had been declined by the corporate body, and opposed by many upholders of 'good old usages,' the bane of all improvements. The bold man, who came prominently forward, when all others had timidly retired, was a simple London tradesman, a goldsmith, dwelling in Basinghall Street, named Hugh Myddelton. He was of Welsh parentage, the sixth son of Richard Myddelton, who had been governor of Denbigh Castle during the reigns of Edward VI, Mary, and Elizabeth. He was horn on his father's estate at Galch Hill, close to Denbigh, 'probably about 1555,' says his latest biographer, Mr. Smiles, for 'the precise date of his birth is unknown.' At the proper age, he was sent to London, where his elder brother, Thomas, was established as a grocer and merchant-adventurer, and under that brother's care he commenced his career as a citizen by being entered an apprentice of the Goldsmith's Company. In clue time he took to business on his own account, and, like his brother, joined the thriving merchant-adventurers. In 1597, he represented his native town of Denbigh in parliament, for which he obtained a charter of incorporation, desiring further to serve it by a scheme of mining for coal, which proved both unsuccessful and a great loss to himself. His losses were, however, well covered by his London business profits, to which he had now added cloth manufacturing. On the accession of James I, he was appointed one of the royal jewellers, being thus one of the most prosperous and active of citizens. The due supply of pure spring water to the metropolis, had often been canvassed by the corporation. At times it was inconveniently scanty; at all times it was scarcely adequate to the demand, which increased with London's increase. Many projects had been brought before the citizens to convey a stream toward London, but the expense and difficulty had deterred them from using the powers with which they had been invested by the legislature; when Myddelton declared himself ready to carry out the great work, and in May 1609 'the dauntless Welshman' began his work at Chadwell, near Ware. The engineering difficulties of the work and its great expense were by no means the chief cares of Myddelton; he had scarcely began his most patriotic and useful labours, ere he was assailed by an outcry on all sides from land-owners, who declared that his river would cut up the country, bring water through arable land, that would consequently be overflowed in rainy weather, and converted into quagmires; that nothing short of ruin awaited land, cattle, and men, who mightbe in its course; and that the king's highway between London and Ware would be made impassable! All this mischief was to befall the country-folks of Hertfordshire and Middlesex for Mr. Myddelton's 'own private benefit,' as was boldly asserted, with a due disregard of its great public utility; and ultimately parliamentary opposition was strongly invoked. Worried by this senseless but powerful party, with a vast and expensive labour only half completed, and the probability of want of funds, most men would have broken down in despair and bankruptcy; Myddelton merely sought new strength, and found it effectually in the king. James I joined the spirited contractor, agreed to pay one-half of the expenses in consideration of one-half share in its ultimate profits, and to repay Myddelton one-half of what he had already disbursed. This spirited act of the king silenced all opposition, the work went steadily forward, and in about fifteen months after this new contract, the assembly took place at the New River Head, in the fields between Islington and London, to witness the completion of the great work, as we have already described it.  The pencil of the honest and indefatigable Hollar has preserved to us the features of this interesting locality, and we copy his view above. Mr. Smiles observes that 'the site of the New River Head had always been a pond, 'an open idell poole,' says Hawes, 'commonly called the Ducking-pond; being now by the master of this work reduced into a comley pleasant shape, and many ways adorned with buildings.' The house adjoining it, belonging to the company, was erected in 1613.' Hollar's view indicates the formal, solid, aspect of the place, and is further valuable for the curious view of Old London in the back-ground; the eye passing over Spa-fields, and resting on the city beyond; the long roof of St. Paul's Cathedral appearing just above the boundary-wall of the New River Head; and the steeple of Bow Church to the extreme left. This view was fortunately sketched the year before the great fire, and is consequently unique in topographical value. James I seems to have been fully aware, at all times, of Myddelton's merit, and anxious to help and honour it. Some years afterwards, when he had temporarily reclaimed Brading Harbour, Isle of Wight, from the sea, the king raised him to the dignity of baronet without the payment of the customary fees, amounting to £1095, a very large sum of money in those days. A few words must suffice to narrate Myddelton's later career. He sold twenty-eight of his thirty-six shares in the New River soon after its completion. With the large amount of capital this gave him to command, he carried out the work at Eroding, just alluded to. He then directed his attention to mining in North Wales, and continued to work the mines with profit for a period of about sixteen years. The lead of these mines contained much silver, and a contemporary declares that he obtained of puer silver 100 poundes weekly,' and that his total profits amounted to at least £2000 a month. 'The popular and oft-repeated story of Sir Hugh having died in poverty and obscurity, is only one of the numerous fables which have accumulated about his memory,' observes Mr. Smiles. 'There is no doubt that Myddelton realised considerable profits, by the working of his Welsh mines, and that toward the close of his life he was an eminently prosperous man.' He died at the advanced age of seventy-six, leaving large sums to his children, an ample provision for his widow, many bequests to friends and relatives, annuities to servants, and gifts to the poor. All of which it has been Mr. Smiles's pleasant task to prove from documentary evidence of the most unimpeachable kind.  In order to fully comprehend the value of Myddelton's New River to the men of London, we must take a retrospective glance at the older water supply. Two or three conduits in the principal streets, some others in the northern suburbs, and the springs in the neighbourhood of the Fleet River, were all they had at their service. The Cheapside conduits were the most used, as they were the largest and most decorative of these structures. The Great Conduit in the centre of this important thoroughfare, was an erection like a tower, surrounded by statuary; the Little Conduit stood in Westcheap, at the back of the church of St. Michael, in the Querne, at the north-east end of Paternoster Row. Our cut exhibits its chief features, as delineated in 1585 by the surveyor R. Treswell. Leaden pipes ran all along Cheapside, to convey the water to various points; and the City Records tell of the punishment awarded one dishonest resident, who tapped the pipe where it passed his door, and secretly conveyed the water to his own well. Except where conveyed to some public building, water had to be fetched for domestic use from these ever-flowing reservoirs. Large tankards, holding from two to three gallons, were constructed for this use; and may be seen ranged round the conduit in the cut above given.  Many poor men lived by supplying water to the householders; 'a tankard-bearer' was hence a well-known London character, and appears in a curious pictorial series of the cries of London, executed in the reign of James I, and preserved in the British Museum. It will be seen from our copy, that he presents some peculiar professional features. His dress is protected by coarse aprons hung from his neck, and the weight of his large tankard when empty, partially relieved from the left shoulder, by the aid of the staff in his right hand.. He wears the 'city fiat-cap,' his dress altogether of the old fashion, such as belonged to the time of 'bluff King Hal.' When water was required in smaller quantities, apprentices and servant-girls were sent to the conduits. Hence they were not only gossiping-places, but spots where quarrels constantly arose. A curious print in the British Museum-published about the time of Elizabeth-entitled Tittle Tattle, is a satire on these customs, and tells us in homely rhyme: At the conduit striving for their turn, The quarrel it grows great, That up in arias they are at last, And one another beat. Oliver Cob, the water-bearer, is one of the characters in Ben Jonson's play, Every Man in his Humour, and the sort of coarse repartee he indulges in, may be taken as a fair sample of that used at the London conduits. It was not till a consider-able time after the opening of the New River that their utility ceased. Much difficulty and expense awaited the conduct of water to London houses. The owners of the ground near the New River Head exacted heavy sums for permission to carry pipes through their land, and it was not till February 1626, that Bethlehem Hospital was thus supplied. The profits of the New River Company were seriously affected by these expenses, until they secured themselves from exaction by the purchase of the land. The pipes they used for the conveyance of their water were of the simplest construction, formed of the stems of small elm-trees, merely denuded of the bark, drilled through the centre, cut to lengths of about six feet; one end being tapered, so that it fitted into the orifice of the pipe laid down before it; and in this way wooden pipes passed through the streets to the extent of about 400 miles! The fields known as 'Spa-fields,' near the New River Head, were used as a depot for these pipes; and were popularly termed 'the pipe-fields' by the inhabitants of Clerkenwell.  As the conveyance of water by means of those pipes was expensive to the company, and charged highly in consequence, water-carriers still plied their trade. Lauren, an artist who has depicted the street-criers of the time of William III, has left us the figure of the water-carrier he saw about London, crying, 'Any New River water here!' A penny a pailfull was his charge for porterage, and he occasionally enforced the superiority of his mode of serving it by crying, 'Fresh and fair New River water! none of your pipe-sludge!' The wooden pipes leaked considerably, were liable to rapid decay, burst during frosts, and were always troublesome; cast-iron pipes have now entirely superseded them, but this is only within the last twenty-five years; and it may be worth noting herethe curious fact, that the rude old elm-tree water-pipes were taken up and removed from before the houses in Piccadilly, extending from the Duke of Devonshire's to Clarges Street, so recently as the year before last; and. that a similar series were exhumed from Pall Mall about five years ago. CEREMONIES FORMERLY CONNECTED WITH THE ELECTION OF THE MAYOR OF NOTTINGHAMOn the day the new mayor assumed office (September 29), he, the old mayor, the aldermen, and councillors, all marched in procession to St. Mary's Church, where divine service was said. After service the whole body went into the vestry, where the old mayor seated himself in an elbow-chair at a table covered with black cloth, in the middle of which lay the mace covered with rosemary and sprigs of bay. This was termed the burying of the mace, doubtless a symbolical act, denoting the official decease of its late holder. A form of electing the new mayor was then gone through, after which the one retiring from office took up the mace, kissed it, and delivered it into the hand of his successor with a suitable compliment. The new mayor then proposed two persons for sheriffs, and two for the office of chamberlains; and after these had also gone through the votes, the whole assemblage marched into the chancel, where the senior coroner administered the oath to the new mayor in the presence of the old one, and the town-clerk gave to the sheriffs and chamberlains their oath of office. These ceremonies being over, they marched in order to the New Hall, attended by such gentlemen and tradesmen as had been invited by the mayor and sheriffs, where the feasting took place. On their way, at the Weekday-Cross, over against the ancient Guild Hall, the town-clerk proclaimed the mayor and sheriffs; and at the next ensuing market-day they were again proclaimed in the face of the whole market at the Malt Cross. The entertainment given as a banquet on these occasions will perhaps astonish some of their successors in office. 'The mayor and sheriffs welcomed their guests with bread and cheese, fruit in season, and pipes and tobacco.' Imagine the present corporation and their friends sitting down to such a feast! |