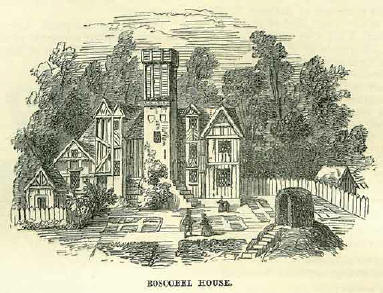

29th MayBorn: Charles II of England, 1630, London; Sarah Duchess of Marlborough, 1660; Louis Daubenton, 1716, Montbard; Patrick Henry, American patriot and orator, 1736, Virginia; Joseph Fouche, police minister of Napoleon I, 1763, Nantes. Died: Cardinal Beaton, assassinated at St. Andrew's, 1546; Stephen des Courcelles, learned Protestant divine, 1658, Amsterdam; Dr. Andrew Ducarel, English antiquary, 1785, South Lambeth; Empress Josephine, 1814, Malmaison; W. H. Pyne, miscellaneous writer, 1843, Paddington; Sir Thomas Dick Lauder, Bart., miscellaneous writer, 1848, Edinburgh. Feast Day: St. Cyril, martyr (3rd century?); St. Conon and his son, martyrs, of Iconia in Asia (about 275); St. Maximinus, Bishop of Tiers, 349; Saints Sisinnius, Martyrius, and Alexander, martyrs, in the territory of Trent, 397. CHARLES II's RESTORATIONIt is a great pity that Charles II was so dissolute, and so reckless of the duties of his high station, for his life was an interesting one in many respects; and, after all, the national joy attending his restoration, and his cheerfulness, wit, and good-nature, give him a rather pleasant association with English history. His parents, Charles I and Henrietta Maria (daughter of Henry IV of France), who had been married in 1626, had a child named Charles James born to them in March 1629, but who did not live above a day. Their second infant, who was destined to live and to reign, saw the light on the 29th of May 1630, his birth being distinguished by the appearance, it was said, of a star at midday. It was on his thirtieth birthday, the 29th of May 1660, that the distresses and vicissitudes of his early life were closed by his triumphal entry as king into London. His restoration might properly be dated from the 8th of May, when he was proclaimed as sovereign of the three kingdoms in London: but the day of his entry into the metropolis, being also his birthday, was adopted as the date of that happy event. Never had England known a day of greater happiness. Defend the Commonwealth who may-make a hero of Protector Oliver with highest eloquence and deftest literary art-the intoxicated delight of the people in getting quit of them, and all connected with them, is their sufficient condemnation. The truth is, it had all along been a government of great difficulty, and a government of difficulty must needs be tyrannical. The old monarchy, ill-conducted as it had been under Charles I, shone white by comparison. It was happiness overmuch for the nation to get back under it, with or without guarantees for its better behaviour in future. An army lately in rebellion joyfully marshalled the king along from Dover to London. Thousands of mounted gentleman joined the escort, brandishing their swords, and shouting with inexpressible joy.' Evelyn saw the king arrive, and set down a note of it in his diary. He speaks of the way strewed with flowers; the streets hung with tapestry; the bells madly ringing; the fountains running with wine; the magistrates and the companies all out in their ceremonial dresses-chains of gold, and banners; nobles in cloth of silver and gold; the windows and balconies full of ladies; 'trumpets, music, and myriads of people flocking even so far as from Rochester, so as they were seven hours in passing the city, even from two in the afternoon till nine at night.' 'It was the Lord's doing,' he piously adds; unable to account for so happy a revolution as coming about by the ordinary chain of causes and effects. It belongs more particularly to the purpose of this work to state, that among the acts passed by parliament immediately after, was one enacting 'That in all succeeding ages the 29th of May be celebrated in every church and chapel in England, and the dominions thereof, by rendering thanks to God for the king's peaceable restoration to actual possession and exercise of his legal authority over his subjects,' &c. The service for the Restoration, like that for the preservation from the Gunpowder Treason, and the death of Charles I, was kept up till the year 1859. THE ROYAL OAKThe restoration of the king, after a twelve years' interregnum from the death of his father, naturally brought into public view some of the remarkable events of his intermediate life. None took a more prominent place than what had happened in September 1651, immediately after his Scottish army had been overthrown by Cromwell at Worcester. It was heretofore obscurely, but now became clearly known, that the royal person had for a day been concealed in a bushy oak in a Shropshire forest, while the Commonwealth's troopers were ranging about in search of the fugitives from the late battle. The incident was romantic and striking in itself, and, in proportion to the joy in having the king once more in his legal place, was the interest felt in the tree by which he had been to all appearance providentially preserved. The ROYAL OAK accordingly became one of the familiar domestic ideas of the English people. A spray of oak in the hat was the badge of a loyalist on the recurrence of the Restoration-day. A picture of an oak tree, with a crowned figure sitting amidst the branches, and a few dragoons scouring about the neighbouring ground, was assumed as a sign upon many a tavern in town and country. Some taverns still bear at least the name-one in Paddington, near London). And 'Oak Apple-day' became a convertible term for the Restoration-day among the rustic population. We thus find it necessary to introduce-first, a brief account of the king's connexion with the oak; and, second, a notice of the popular observance still remembered, if not practised, in memory of its preservation of a king. THE KING AT BASCOBLEAfter the defeat of the royal army at Worcester, (September 3rd, 1651,) the king and his principal officers determined on seeking safety by returning along the west of England to Scotland. As they proceeded, however, the king bethought him that the party was too large to make a safe retreat, and if he could get to London before the news of the battle, he might obtain a passage incognito in a vessel for France or Holland. On Kinver Heath they were brought to a stand-still by the failure of their guide to find the way. In the midst of the dismay which prevailed, the Earl of Derby stated to the king that he had lately, when in similar difficulty, been beholden for his life to a place of concealment on the borders of Staffordshire-a place called Boscobel. Another voice, that of Charles Giffard, the proprietor of this very place, broke the silence- 'I will undertake to guide his majesty to Boscobel before daybreak.' It was immediately determined that the king, with a very small party of associates, should proceed under Giffard's care to the promised shelter. By daybreak, Charles had reached White Ladies, a house taking its name from a ruined monastery hard by, and in the possession of Giffard family, who were all Catholics. Here he was kindly received, put into a peasant's dress, and sent off to the neighbouring house of Boscobel, under the care of a dependent of the family, named Richard Penderel. His friends took leave of him, and pursued their journey to the North. Boscobel was a small mansion which had been not long before built by Mr. Giffard, and called so from a fancy of the builder, as being situated in Bosco-bello -Italian for a fair wood. The king knew how suitable it was as a place of concealment, not only from its remote and obscure situation, but because the Catholics always had hiding-holes in their houses for priests. At this time the house was occupied by a family of peasants, named Penderel, whose employment it was to cut and sell the wood, having 'some cows' grass to live upon.' They were simple, upright people, devoted to their master; and, probably from habit as Catholics, accustomed to assist in concealing proscribed persons. Certain it is, the house contains two 'priests' holes,'' one entered by a trap in the floor of a small closet though it does not appear that Charles took any advantage of such a retreat while living at the place. Charles, in his anxiety to make toward London, determined to set out on foot, 'in a country fellow's habit, with a pair of ordinary grey cloth breeches, a leathern doublet, and green jerkin,' taking no one with him but 'trusty Dick Penderel,' as one of the brethren was called; they had, however, scarcely reached the edge of the wood, when a troop of the rebel soldiery obliged them to lie close all day there, in a drenching rain. During this time the king altered his mind and determined to go towards the Severn, and so to France, from some Welsh seaport. At midnight they started on their journey; but after some hair-breadth escapes, finding the journey difficult and dangerous, they returned to Boscobel. Here they found Colonel William Careless, who had seen the last man killed in the Worcester fight, and whom the king at once took into his confidence. Being Sunday, the king kept in the house, or amused himself by reading in the close arbour in the little garden; and the next day he took the colonel's advice, 'to get up into a great oak, in a pretty plain place, where we might see round about us.' This tree was about a bowshot distance from the house. Charles describes it as 'a great oak, that had been lopped some three or four years before, and being grown out again very bushy and thick, could not be seen through.' There Charles and the colonel stayed the whole day, having taken up with them some bread and cheese and small beer, the colonel having a pillow placed on his knees, that the king might rest his head on it as he sat among the branches. While there, they saw many soldiers beating the woods for persons escaped. After an uneasy day, the king left the friendly shelter of Boscobel at midnight, for Mr. Whitgrave's house at Mosely; the day after, he went to Colonel Lane's, at Bently; from whence, disguised as a serving-man, he rode with Lane's sister toward Bristol, intending to take ship there; but after many misadventures and much uncertain rambling, he at last succeeded in obtaining a vessel at Shoreham, in Sussex, which carried him across to Fecamp, in Normandy. The appearance of the lonely house in the wood, that gave such important shelter to the king, has been preserved in a contemporary engraving here copied. It was a roomy, half-timbered building, with a central turret of brick-work and timber, forming the entrance stair. A small portion of the wood was cleared around it for a little enclosed garden, having a few flower-beds, in front of the house; and an artificial 'mount,' with a summer-house upon it, reached by a flight of steps. Here Charles sat during the only Sunday he passed at Boscobel. Blount says: His majesty spent some part of this Lord's-day in reading, in a pretty arbour in Boscobel garden, which grew upon a mount, and wherein there was a stone table, and seats about it; and commended the place for its retiredness.  At the back of this arbour was the gate leading toward the wood where the friendly oak of shelter stood. Dr. Stukely, who visited the place in the early part of the last century, speaks of the oak, as 'not far from Boscobel House, just by a horse track passing through the wood.' The celebrity of the tree led to its partial destruction; Blount tells us, 'Since his majesty's happy restoration, hundreds of people for many miles round have flocked to see the famous Boscobel, which had once the honour to be the palace of his sacred majesty, but chiefly to behold the Royal Oak, which has been deprived of all its young boughs by the numerous visitors, who keep them in memory of his majesty's happy preservation; insomuch, that Mr. Fitzherbert, who was afterwards proprietor, was forced in a due season of the year to crop part of it for its preservation, and put himself to the charge of fencing it about with a high pale, the better to transmit the happy memory of it to posterity.' Stukely, half a century later, says: The tree is now enclosed with a brick wall, the inside whereof is covered with laurel. Close by its side grows a young thriving plant from one of its acorns. Over the door of the enclosure, I took this inscription in marble: 'Felicissimamarborem, quam in asylum potentissimi Regis Caroli IL Deus. 0. M., per quem reges regnant, hic crescere voluit, tam in perpetuam rei tantae memoriam, quam specimen firmae in reges fidei, muro cinctam posteris commendarunt Basilius et Jana Fitzherbert. Quercus amica Jovi. The enclosure has long since disappeared; but the inscription is still preserved in the farmhouse at Boscobel. Burgess, in his Eidodendron, speaking of this tree, says: It succumbed at length to the reiterated attentions of its votaries; and a huge bulk of timber, consisting of many loads, was taken away by handfuls. Several saplings were raised in different parts of' the country from its acorns, one of which grew near St. James's palace, where Marlborough House now stands; and there was another in the Botanic Gardens, Chelsea; the former has long since been felled, and of the latter the recollection seems almost to be lost. On the north side of the Serpentine in Hyde Park, near the powder magazine, flourished two old trees, said to have been planted by Charles II from acorns of the Boscobel oak. They were both blighted in a severe frost a few years ago; one has been entirely removed, but the stem and a few branches of the other still remain, covered with ivy, and protected by an iron fence. In the Bodleian library is preserved a fragment of the original tree, turned into the form of a salver, or stand for a tankard; the inscription upon it records it as the gift of Mrs. Letitia Lane, a member of the family who aided Charles in his escape. It was the intention of the king to institute a new order, into which those only were to be admitted who were eminently distinguished for their loyalty-they were to be styled 'Knights of the Royal Oak;' but these knights were soon abolished, ' it being wisely judged,' says Noble, in his Memoirs of the Cromwell Family, 'that the order was calculated only to keep awake animosities which it was the part of wisdom to lull to sleep.' He adds, that the names of the intended knights are to be seen in the Baronetage, published in 5 vols. 8 vo, 1741, and that Henry Cromwell, 'first cousin, one remove, to Oliver, Lord Protector,' was among the number. This gentleman was a zealous royalist, instrumental in the restoration of the royal family; 'and as he knew the name of Cromwell would not be very grateful in the court of Charles the Second, he disused it, and styled himself only plain Henry Williams, Esq., by which name he was set down in the list of such persons as were to be made Knights of the Royal Oak.' It may be here remarked that the Cromwell family derived its origin from Wales, and that they bore the name of Williams before they assumed that of Cromwell, on the marriage of Richard Williams with the sister of Cromwell Earl of Essex, prime minister of Henry VIII; by which he became much enriched, all grants of dissolved religious houses, &c., passing to him by the names of Richard Williams, otherwise Cromwell. He was great-great-grandfather to Oliver, Lord Protector. At the coronation of Charles II, the first triumphal arch erected in Leadenhall Street, near Lime Street, for the king to pass under on his way from the Tower to Westminster, is described in Ogilby's contemporary account of the ceremony as having in its centre a figure of Charles, royally attired, behind whom, 'on a large table, is deciphered the Royal Oak bearing crowns and sceptres instead of acorns; amongst the leaves, in a label ----------- Miraturque novas Frondes et non sua poma. (----------- Leaves unknown Admiring, and strange apples not her own.) As designing its reward for the shelter afforded his majesty after the battle of Worcester.' In the Lord Mayor's show of the same year, a pageant was placed near the Nag's Head tavern, in Cheapside, 'like a wood, in the vacant part thereof several persons in the habit of woodmen and wood-nymphs disport themselves, dancing about the Royal Oak;' while the rural god Sylvanus indulged in a long and laudatory speech in honour of the celebrated tree. Colonel Careless, the companion of Charles in the oak, was especially honoured at the Restoration, by the change of his name to Carlos, at the king's express desire, that it might thus assimilate with his own; and the grant of 'this very honourable coat of arms, which is thus described in the letters patent, 'upon an oak proper, in a field or, a foss gules, charged with three royal crowns of the second, by the name of Carlos. And for his crest a civic crown, or oak garland, with a sword and sceptre crossed through it saltier-wise.'' The Penderels were also honoured by court notice and a government pension. 'Trusty Dick' came to London, and died in his majesty's service. He was buried in 1671, under an altar tomb in the churchyard of St. Giles's-in-the-Fields, then a suburban parish, and a fitting residence for the honest country woodman. The tomb still preserves its characteristic features, and an epitaph remarkable for a high-flown confusion of ideas and much grandiloquent verbosity. The Barber-Surgeons' Company of London possess a curious memorial of the celebrated tree which sheltered Charles at Boscobel. It is a cup of silver, partially gilt, the stem and body representing an oak tree, from which hang acorns, fashioned as little bells; they ring as the cup passes from hand to hand round the festive board of the Company on great occasions. The cover represents the Royal Crown of England. Though curious in itself as a quaint and characteristic piece of plate, it derives an additional interest from the fact of its having been made by order of Charles the Second, and presented by him to the Company, the Master at that time being Sir Charles Scarborough, who was chief physician to the king. OAKS-APPLES DAYThere are still a few dreamy old towns and villages in rural England where almost every ruin that Time has unroofed, and every mouldering wall his silent teeth have gnawed through, are attributed to the cannon of Cromwell and his grim Ironsides; though, in many instances, history has left no record that either the stern Protector or his dreaded troopers were ever near the spot. In many of these old-fashioned and out-of-the-way places, the 29th of May is still celebrated, in memory of King Charles's preservation in the oak of Boscobel, and his Restoration. The Royal Oak is also a common alehouse sign in these localities, on which the Merry Monarch is pictured peeping through the branches at the Roundheads below, looking not unlike some boy caught stealing apples, who dare not descend for fear of the owners of the fruit. Oak Apple-day is the name generally given to this rural holiday, which has taken the place of the old May-day games of our more remote ancestors; though the Maypoles are still decorated and danced around on the 29th of this month, as they were in the more memorable May-days of the olden time. But Oak Apple-day is not the merry old May-day which our forefathers delighted to honour. Sweet May, as they loved to call her, is dead; for although they still decorate the May-pole with flowers, and place a garish figure in the centre of the largest garland, it is but the emblem of a dead king now, instead of the beautiful nymph which our ancestors typified, wreathed with May-buds, and scattering flowers on the earth, and which our grave Milton pictured as the flowery May, that came 'dancing from the East,' and throwing from her green lap The yellow cowslip and the pale primrose! On the 29th of May-one of the bright holidays of our boyish years-we were up and away at the first peep of dawn to the woods, to gather branches of oak and hawthorn, so that we might bring home the foliage and the May-buds as green and white and fresh as when the boughs were unbroken, and the blossoms ungathered. Many an old man and woman, awakened out of their sleep as we went sounding our bullock-horns through the streets at that early hour, must have wished our breath as hushed as that of Cromwell or King Charles, as the horrible noise we made rang through their chambers. Some, perhaps, would awaken with a sigh, and, recalling the past, he half dreaming of the old years that had departed, when they were also young, and rose with the dawn as we did, and went out with merry hearts a-Maying. We were generally accompanied by a few happy girls-our sisters, or the children of our neighbours-whose mothers had gone out to bring home May-blossoms when they were girls and their husbands boys, as we then were. The girls brought home sprays of hawthorn, sheeted over with moonlight-coloured May-blossoms, which, along with wild and garden flowers, they wove into the garlands they made to hang in the oak branches, across the streets, and on the May-pole; and great rivalry there was as to which girl could make the handsomest May-garland. If it were a dewy morning, the girls always bathed their faces in May-dew, to make them fair. It was our part to cut down and drag, or carry home huge branches of oak, with which, as Her-rick says, we made ' each street a park- green, and trimmed with trees.' Beautiful did the old woods look in the golden dawn, while the dewy mist still hung about the trees, and nothing seemed awake but the early birds in all that silent land of trees. We almost recall the past with regret, as we remember how we stopped the singing of ' those little angels of the trees,' by blowing our unmelodious horns; and marvel that neither Faun nor Dryad arose to drive us from their affrighted haunts. We climbed the huge oaks like the Druids of old, and, although we had no golden pruning-hooks, we were well supplied with saws, axes, and knives, with which we hacked and hewed at the great branches, until they came down with a loud crash, sometimes before we were aware, when we now and then came down with the boughs we had been bestriding. Very often the branches were so large, we were compelled to make a rude hurdle, on which we dragged them home; a dozen of us hauling with all our strength at the high pile of oak-boughs, careful to keep upon the road-side grass, lest the dust should soil the beautiful foliage. Yet with all our care there was the tramp of the feet of our companions beside us along the dusty highway; and though the sun soon dried up the dew which had hung on the fresh-gathered leaves, it was no longer the sweet green oak that decorated the woods-no longer the maiden May, with the dew upon her bloom-but a dusty and tattered Doll Tear-sheet, that dragged her bemired green skirt along the street, compared with the vernal boughs and sheeted blossoms we had gathered in the golden dawn. Many a wreck of over-reaching ambition strewed the roadway from the woods, in the shape of huge oaken branches which the spoilers had cast aside, after toiling under the too weighty load until their strength was exhausted. Publicans, and others who could afford it, would purchase the biggest branches that could be bought of poor countrymen, or others whom they sent out-for there was great rivalry as to who should have the largest bough at his door; and wherever the monster branch was placed, that we made our head-quarters for the day, and there was heard the loudest sounding of horns. Neither the owners of the woods, gamekeepers, nor woodmen interfered with us, beyond a caution not to touch the young trees; for lopping a few branches off the large oaks was never considered to do them any harm, nor do we remember that ever a summons was issued for trespassing on the 29th of May. Beautiful did these old towns and villages look, with their long lines of green boughs projecting from every house, while huge gaudy garlands of every colour hung suspended across the middle of the streets, which, as you looked at them in the far distance, seemed to touch one another, like lighted lamps at the bottom of a long road, forming to appearance one continuous streak of fire. Then there were flags hung out here and there, which were used at the club-feasts and Whitsuntide holidays-red, blue, yellow, purple, and white blending harmoniously with the green of the branches and their gilded oak-apples, and the garlands that were formed of every flower in season, and rainbow-coloured ribbons that went streaming out and fluttering in the wind, which set all the banners in motion, and gave a look of life to the quiet streets of these sleepy old towns. But as all is not gold that glitters, so were those gaudy-looking garlands not altogether what they appeared-for ribbons were expensive, and we were poor; so we hoarded up our blue sugar-paper, and saved clean sheets of our pink blotting-paper, with other sheets of varied colour-and these, when made up into bows, and shaped like flowers, and hung too high over head for the cheat to be discovered, might be taken for silk, as the gilded oak-apples might pass for gold; and many a real star or ribbon, which. the ambitious wearers had wasted a life to obtain, were never worn nor gazed upon with greater pleasure than that afforded us by the cunning of our own hands. And in these garlands were hung the strings of birds' eggs we had collected from hundreds of nests--some of us contributing above a hundred eggs-which were strung like pearls. Those of the great hawks, carrion crows, rooks, magpies, and such like, in the centre, and dwindling Fine by degrees, and beautifully less, to the eggs of the tiny wren, which are not larger than a good-sized pea. No doubt it is as cruel to rob birds'-nests as it is to sack cities; but as generals must have spoil for their soldiers, so we believed we could not have garlands with-out plundering the homes of our sweet singing-birds, to celebrate the 29th of May. Tired enough at night we were, through having risen so early, and pacing about all day long; and sore and swollen were our lips, through blowing our horns so many hours; and yet these rural holidays bring back pleasant memories -for time might be worse misspent than in thus celebrating the 29th of May. T. M. CAVALIER CLAIMSThe dispensers of patronage under the Restoration had no enviable office. The entry of Charles II into his kingdom was no sooner known, than all who had any claim, however slight, upon royal consideration, hastened to exercise the right of petition. Ignoring the Convention of Breda, by which the king bound himself to respect the status quo as far as possible, the nobility and gentry sought to recover their alienated estates, clergymen prayed to be rein-stated in the pulpits from which they had been ejected, and old placeholders demanded the removal of those who had pushed them from their official stools. Secretary Nicholas was overwhelmed with claims on account of risks run, sufferings endured, goods supplied, and money advanced on behalf of the good cause; petitions which might have been endorsed, like that of the captain who entreated the wherewithal to supply his wants and pay his debts, 'The king says he cannot grant anything in this kind till his own estates be better settled.' The Calendar of State Papers for the year 1660 is little else than a list of royalist grievances, for the bulk of documents to which it forms an index are cavalier petitions. As might be expected, it is rather monotonous reading; still, some interesting and curious details may be gathered from its pages. The first petition preserved therein is that of twenty officers of the Marquis of Hertford's Sherborne troop, who seek to be made partakers of the universal joy by receiving some provision for the remainder of their days; 'the late king' having promised that they should have the same pay as long as they lived.' The gallant twenty seem to have thought, with Macbeth, that if a thing was to be done, it were well it were done quickly, for their petition is dated the 29th of May. It is true the numeral is supplied by Mrs. Green, but even giving them the benefit of the doubt, it is evident that the appeal must have been presented within three days of Charles II's ascension to the throne. If that monarch had endorsed all the promises of his father, he would have made some curious appointments; a quartermaster of artillery actually applies for the office of king's painter, the patron of Vandyke ' having promised him the office on seeing a cannon painted by him when he came with the artillery after the taking of Hawksby House.' Another artillery officer, Colonel Dudley, puts forth somewhat stronger claims for reward, having lost £2000 and an estate of £200 a-year, had his sick wife turned out of doors, his men taken, 'one of them, Major Harcourt, being miserably burned with matches, and himself stripped and carried in scorn to Worcester, which he had fortified as general of artillery, where he was kept under double guard; but escaped, and being pursued, he took to the trees in the daytime, and travelled in the night till he got to London; was retaken, brought before the Committee of Insurrection, sent to the gate-house, and sentenced to be shot; but escaped with Sir H. Bates and ten others during sermon-time; lived three weeks in an enemy's haymow, went on crutches to Bristol, and escaped.' George Paterick asks a place in his majesty's barge, having served the late king sixteen years by sea and land; been often imprisoned, twice tried for his life, and three times banished the river, and forbidden to ply as a waterman. One soldier solicits compensation for fifteen wounds received at Edgehill, and another for his sufferings after Worcester fight, when 'the barbarous soldiers of the grand rebel, Cromwell, hung him on a tree till they thought him dead.' The Cromwellian system of colonization is aptly illustrated by the petition of Lieut. Col. Hunt, praying his majesty to order the return of thirty soldiers taken prisoners at Salisbury, 'who were sold as slaves in Barbadoes;' and by that of John Fowler, captain of pioneers at Worcester, 'sent by the rebels to the West Indies as a present to the barbarous people there, which, penalty he under-went with, satisfaction and content.' The evil case to which the exiled king had been reduced is exemplified by the complaint of 'his majesty's regiment of guards in Flanders,' that they had not received a penny for six months, and were compelled to leave officers in prison for their debts, before they could march to their winter quarters at Namur, where their credit was so bad, that the officers had to sell their clothes, ' some even to their last shirt,' to procure necessaries. The brief abstracts of the memorials of less active partisans speak even more eloquently of the misery wrought by civil strife. Thomas Freebody solicits admission among the poor knights of Windsor, having been imprisoned seven times, banished twice, and compelled on three occasions to find sureties for a thousand pounds. James Towers was forced, on account of his loyalty, to throw dice for his life; and, winning the cast, was banished. Thomas Holyoke, a clergyman, saw his aged father forced from his habitation, his mother beaten so that her death was hastened, his servant killed, while he was deprived of property bringing in £300 a-year, and obliged to live on the charity of commiserating friends. Another clergyman recounts how he suffered imprisonment for three years, and was twice corporally punished for preaching against rebellion and using the Common Prayer-book. Sir Edward Pierce, advocate at Doctors' Commons, followed Charles I to York as judge marshal of the army, which he augmented by a regiment of horse. He lost thereby his property, his profession, and his books; 'was decimated and imprisoned, yet wrote and published at much danger and expense many things very serviceable to king and church.' Abraham Dowcett supplied the late king with pen and ink, at hazard of his life conveyed letters between him and his queen, and afterwards plotted his escape from Carisbrook Castle, for which he was imprisoned and his property sequestrated. The brothers Samburne seem to have earned the commissionership of excise, for which they petition. After being exiled for executing several commissions on behalf of both the king and his father, and spent £25,000 in supplying war material to their armies, they transmitted letters for the members of the royal family, 'when no one else would sail;' and when Charles II arrived at Rouen, after the battle of Worcester, James Samburne was the only person to whom he made himself known, or whom he would entrust with dispatches to the queen-mother. The Samburnes further assisted Charles by prevailing upon a Mr. Scott to advance him 'money for Paris,' and religiously preserved a portion of his majesty's disguise as a precious relic. Lady petitioners muster strong, and for the most part show good cause why their prayers should be granted. Some of them afford remarkable proof of what women will do and suffer for a cause with which they sympathize. Katherine de Luke asks for the lease of certain waste lands near Yarmouth; she served Charles I by carrying letters when none else durst run the risk, for which she was sent to Bridewell, and whipped every other day, burnt with lighted matches, and otherwise tortured to make her betray her trust. Her husband died of his wounds, her son was sold to slavery, and she herself obliged to live abroad for sixteen years. Elizabeth Cary, an aged widow, was imprisoned in Windsor Castle, Newgate, Bridewell, the Bishop of London's house, and lastly in the Mews, at the time of the late king's martyrdom, for peculiar service in carrying his majesty's gracious proclamation and declaration from Oxford to London. She had her back broken at Henley-on-Thames, where a gibbet was erected for her execution. This extremity she escaped, and succeeded in finding shelter in her own county. Her loyalty was rewarded by a pension of £40 a-year. Elizabeth Pinckney, who buried her husband after Reading fight, seeks the continuation of an annuity of £20 he had earned by thirty-six years' service. She complains that since 1643 she had waited on all parliaments for justice, 'but they have imprisoned her, beaten her with whips, kicked, pulled, and torn her, till shame was cried upon them.' Ann Dartigueran says her father lost his life in the cause, leaving her nothing but sadness to inherit. Mrs. Mary Graves certainly deserved well of the restored monarch; for when he made his last attempt to recover his crown by force, she sent him twelve horses, ten furnished with men and money, and two empty, on one of which the king rode at Worcester, escaping from the field on the other. This service cost the loyal lady her liberty, an estate of £600 a-year, and two thousand pounds' worth of personal property. Nothing daunted, she prevailed upon her husband to let her send provisions from Ireland to Chester in aid of Sir George Booth's rising, for which she was again imprisoned, and her remaining property seized. In a second appeal, Mrs. Graves says she sent one Francis Yates to conduct his majesty out of Worcester to Whitehaven, for doing which he was hung; and she had been obliged to maintain his widow and five children ever since. To this petition is appended a paper, signed by Richard Penderel, certifying that Edward Martin was tenant of White Ladies, where Charles hid himself for a time, disguised in a suit of his host; and further, that Francis Yates's wife was the first person to give the fugitive prince any food after the defeat, which he ate in a wood, upon a blanket. Charles afterwards borrowed ten shillings of Yates himself, ' for a present necessity,' and ' was pleased to take his bill out of his hand and kept it in his own, the better to avoid suspicion;' Yates seeing his charge safe from Boscobel to Mosely, a service which, as is stated above, cost the faithful yeoman his life. After such stories of suffering and devotion, one has no sympathy to spare for Robert Thomas, whose principal claim upon royal consideration seems to be his having lost his mother, 'who was his majesty's seamstress from his birth;' or for one Maddox, who seeks a reappointment as tailor to the crown, excusing himself for not waiting upon his customer for twelve years by a vague assertion of being prevented by 'sufferings for his loyalty.' An old man of ninety-five asks to be restored to his post of cormorant-keeper, an office conferred on him by James I; and another claims favour for 'having served his majesty in his young days as keeper of his batoons, paumes, tennis-shoes, and ankle-socks.' E. Fawcett, too, who taught his majesty to shoot with the long-bow, 'an exercise honoured by kings and maintained by statutes,' solicits and obtains the office of keeper of the long-bows; having in anticipation provided four of the late king's bows, with all necessaries, for the use of his majesty and his brothers, when they shall be inclined to practise the ancient art. Edward Harrison, describing himself as 70 years old, and the father of twenty-one children, encloses a certificate from the Company of Embroiderers, to the effect that he is the ablest workman living. He wishes to be reappointed embroiderer to the king, having filled that situation under James, and having preserved the king's best cloth of state and his rich carpet embroidered in pearls from being cut in pieces and burnt, and restored them with other goods to is majesty. While Robert Chamberlain prays for a mark of favour before going to his grave, being 110 years of age, Walter Braems asks for a collectorship of customs, for 'being fetched out of his sick bed at fourteen years old and carried to Dover Castle, and there honoured by being the youngest prisoner in England for his majesty's service.' John Southcott, with an eye to the future, wants to be made clerk of the green cloth to his majesty's children, 'when he shall have issue; 'and Squire Beverton, Mayor of Canterbury, is encouraged to beg a receivership because his majesty was pleased to acknowledge his loyalty, on his entry into Canterbury, 'with gracious smiles and expressions.' To have satisfied the many claims put forward by those who had espoused the royal cause, Charles II needed to have possessed the wealth of a Lydian monarch and the patronage of an American president. As it was, he was compelled to turn a deaf ear to most suppliants, at the risk of their complaining, as one unsuccessful petitioner does, that 'those who are loyal have little encouragement, being deprived of the benefit of the law; destitute of all favours, countenances, and respect; and left as a scorn to those who have basely abused them.' INEDITED AUTOGRAPHS SARAH DUCHESS OF MARLBOROUGHSarah Jennings, the wife of the great general, John Duke of Marlborough, has been painted in terms far too black by Lord Macaulay, a fact easily to be accounted for by her coming into opposition to his lordship's hero, King William. Her worst fault was her imperious temper. It was her destiny to become the intimate friend of King James's second daughter, the Princess Anne, a gentle and timid woman of limited understanding, who, in her public career, felt the necessity of a strong-minded female friend to lean upon. There is something very conciliating in the account her grace gives of the commencement of her friendship with the princess. Anne justly deemed a feeling of equality necessary for friendship. 'She grew uneasy to be treated by me with the form and ceremony due to her rank; nor could she hear from me the sound of words which implied in them distance and superiority. It was this turn of mind that made her one day propose to me, that whenever I should happen to be absent from her, we might in all our letters write ourselves by feigned names, such as would import nothing of distinction of rank between us. Morley and Freeman were the names her fancy hit upon; and she left me to choose by which of them I would be called. My frank, open temper, naturally led me to pitch upon Freeman, and so the princess took the other; and from this time Mrs. Morley and Mrs. Freeman began to converse as equals, made so by affection and friendship.' Through the reign of her father, when in difficulties from his wish to make her embrace the Catholic faith-through that of William and Mary, when called upon by those sovereigns, her cousin and sister, to give up her friendship with the duchess, because of the duke having become odious to them-Anne maintained her love for Mrs. Freeman; but when she became queen, a series of unfortunate circumstances led her to withdraw her attachment. The queen now disliked the duke, and another and humbler confidante, Mrs. Masham, had engaged her affections. It was in vain that Sarah sought to replace herself on the old footing with Mrs. Morley. She had to drink to the dregs the bitter cup of the discarded favourite.- Her narrative of this distressing crisis, and particularly of her last interview with the queen-when with tears, but in vain, she entreated to be told of any fault she had committed-can scarcely be read without a feeling of sympathy. She could not help at last telling the queen that her majesty would yet suffer for such an instance of inhumanity; to which the only answer was, 'That will be to myself.' And then they parted, to meet no more. She quotes a letter of her husband on the subject: 'It has always,' he says, 'been my observation in disputes, especially in that of kindness and friendship, that all reproaches, though ever so just, serve to no end but making the breach wider. I cannot help being of opinion, that, however in-significant we are, there is a power above that puts a period to our happiness or unhappiness. If anybody had told me eight years ago, that after such great success, and after you had been a faithful servant twenty-seven years, we should be obliged to seek happiness in a private life, I could not have believed that possible.' LONG INTERMISSIONThere is a well-known anecdote of a silent man, who, riding over a bridge, turned about and asked his servant if he liked eggs, to which the servant answered, 'Yes;' whereupon nothing more passed till next year, when, riding over the same bridge, he turned about to his servant once more, and said, 'How?' to which. the instant answer was, 'Poached, sir.' Even this sinks, as an example of long intermission of discourse, beside an anecdote of a minister of Campsie, near Glasgow. It is stated that the worthy pastor, whose name was Archibald Denniston, was put out of his charge in 1655, and not replaced till after the Restoration. He had, before leaving his charge, begun a discourse, and finished the first head. At his return in 1661, he took up the second, calmly introducing it with the remark that 'the times were altered, but the doctrines of the gospel were always the same.' In the newspapers of July 1862, there appeared a paragraph which throws even the minister of Campsie's interrupted sermon into the shade. It was as follows: 'At the moment of the destruction of Pompeii by an eruption of Mount Vesuvius, A.D. 79, a theatrical representation was being given in the Amphitheatre. A speculator, named Langini, taking advantage of that historical reminiscence, has just constructed a theatre on the ruins of Pompeii; and the opening of which new theatre he announces in the following terms: -'After a lapse of 1800 years, the theatre of the city will be reopened with La Figlia del Reggimento. I solicit from the nobility and gentry a continuance of the favor constantly bestowed on my predecessor, Marcus Quintius Martius; and beg to assure them that I shall make every effort to equal the rare qualities he displayed during his management.'' |