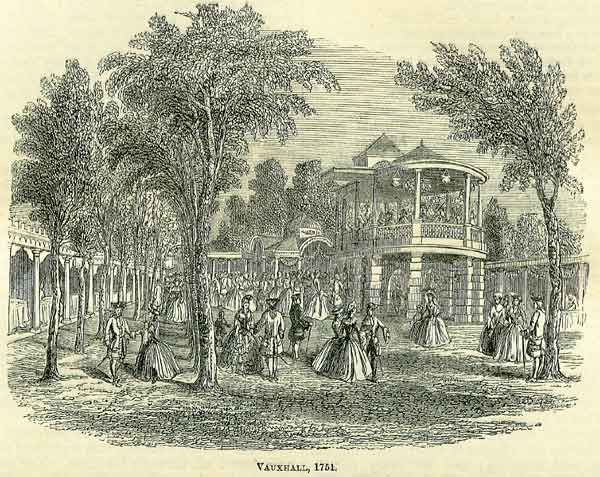

28th MayBorn: James Sforza, the Great, 1639, Cotignola; George I of England, 1660; John Smeaton, engineer, 1724, Ansthorpe; William Pitt, minister of George III, 1759, Hayes, Kent; Thomas Moore, poet, 1780, Dublin. Died: St. Bernard of Savoy, 1008; Thomas Howard, Earl of Suffolk, 1626, Walden; Admiral de Tourville, 1701, Paris; Madame de Montespan, mistress of Louis XIV, 1708; Electress Sophia of Hanover, 1714; George Earl Mareschal, 1778, Potsdam; Bishop Richard Hurd, 1808, Hartlebury; William Eden, Lord Auckland, 1814; Sir Humphry Davy, chemist, 1829, Geneva; William Erskine (Memoirs of Emperor Baber, &c.), 1852, Edinburgh. Feast Day: St. Caraunus (Cheron), martyr, 5th century. St. Germanus, Bishop of Paris, 576. THOMAS MOOREThe public is well aware of Moore's life in outline: that he was the son of a grocer in Aungier Street, in Dublin; that he migrated at an early period of life to London, and there, and at his rural retreat near Devizes, produced a brilliant succession of poems, marked by a manner entirely his own,-also several prose works, chiefly in biography; that he was the friend of Byron, Rogers, Scott, and Lord John Russell, and a favourite visitor of Bowood, Holland House, and other aristocratic mansions;-a bright little man, of the most amiable manners and the pleasantest accomplishments. whom everybody liked, whom Ireland viewed with pride, and whom all. Britain mourned. In 1835, Moore visited his native city, and, led by his usual kindly feelings, sought out the house in Aungier Street in which he had boon born, and where he spent the first twenty years of his life. The account he gives of this visit in his Diary is, to our apprehension, a poem, and one of the finest he ever wrote. 'Drove about a little,' he says, 'in Mrs. Meara's car, accompanied by Hume, and put in practice what I had long been contemplating-a visit to No. 12, Aungier Street, the house in which I was born. On accosting the man who stood at the door, and asking whether he was the owner of the house, he looked rather gruffly and suspiciously at me, and answered, 'Yes; 'but the moment I mentioned who I was, adding that it was the house I was born in, and that I wished to be permitted to look through the rooms, his countenance brightened up with the most cordial feeling, and seizing me by the hand, he pulled me along to the small room behind the shop (where we used to break-fast in old times), exclaiming to his wife (who was sitting there), with a voice tremulous with feeling, 'Here's Sir Thomas Moore, who was born in this house, come to ask us to let him see the rooms; and it's proud I am to have him under the old roof.' He then without delay, and entering at once into my feelings, led me through every part of the house, beginning with the small old yard and its appurtenances, then the little dark kitchen where I used to have my bread and milk in the morning before I went to school; from thence to the front and back drawing-rooms, the former looking more large and respectable than I could have expected, and the latter, with its little closet, where I remember such gay supper-parties, both room and closet fuller than they could well hold, and Joe Kelly and Wesley Doyle singing away together so sweetly. The bedrooms and garrets were next visited, and the only material alteration I observed in them was the removal of the wooden partition by which a little corner was separated off from the back bedroom (in which the two apprentices slept) to form a bedroom for me. The many thoughts that came rushing upon me in thus visiting, for the first time since our family left it, the house in which I passed the first nineteen or twenty years of my life, may he more easily conceived than told; and I must say, that if a man had been got up specially to conduct me through such a scene, it could not have been done with more tact, sympathy, and intelligent feeling than it was by this plain, honest grocer; for, as I re-marked to Hume, as we entered the shop, 'Only think, a grocer's still! ' When we returned to the drawing-room, there was the wife with a decanter of port and glasses on the table, begging us to take some refreshment; and 1 with great pleasure drank her and her good husband's health. When I say that the shop is still a grocer's, I must add, for the honour of old times, that it has a good deal gone down in the world since then, and is of a much inferior grade of grocery to that of my poor father-who, by the way, was himself one of nature's gentlemen, having all the repose and good breeding of manner by which the true gentleman in all classes is distinguished. Went, with all my recollections of the old shop about me, to the grand dinner at the Park [the Lord-Lieutenant's palace]; company forty in number, and the whole force of the kitchen put in requisition. Sat at the head of the table, next to the carving aide-de-camp, and amused myself with reading over the menu, and tasting all the things with the most learned names.' SIR HUMPHRY DAVYDr. John Davy, in his interesting Memoirs of the Life of [his brother] Sir Humphry Davy, relates with much feeling the latter days of the great philosopher. A short while before his death, being at Rome, he mended a little, and as this process went on, 'the sentiment of gratitude to Divine Providence was overflowing, and he was most amiable and affectionate in manner. He often inculcated the propriety, in regard to happiness, of the subjugation of self, as the very bane of comfort, and the most active cause of the dereliction of social duties, and the destruction of good and friendly feelings; and he expressed frequently the intention, if his life were spared, of devoting it to purposes of utility (seeming to think lightly of what he had done already), and to the service of his friends, rather than to the pursuits of ambition, pleasure, or happiness, with himself for their main object.' A BISHOP'S GHOSTHenry Burgwash, who became Bishop of Lincoln on the 28th of May 1320, is chiefly memorable on account of a curious ghost story recorded of him in connexion with the manor of Fingest, in Bucks. Until the year 1845, Buckinghamshire was in the diocese of Lincoln, and formerly the bishops of that see possessed considerable estates and two places of residence in the county. They had the palace of Wooburn, near Marlow, and a manorial residence at Fingest, a small secluded village near Wycomb. Their manor-house of Fingest, the ruins of which still exist, stood near the church, and was but a plain mansion, of no great size or pretensions. And why those princely prelates, who possessed three or four baronial palaces, and scores of manor-houses superior to this, chose so often to reside here, is unknown. Perhaps it was on account of its sheltered situation, or from its suitableness for meditation, or because the surrounding country was thickly wooded and well stocked with deer; for in the 'merrie days of Old England,' bishops thought no harm in heading a hunting party. Be this as it may, certain it is that many of the early prelates of Lincoln, although their palace of Wooburn was near at hand, often preferred to reside at their humble manor-house of Fingest. One of these was Henry Burgwash, who has left reminiscences of his residence here more amusing to posterity than creditable to himself. 'He was,' says Fuller, 'neither good for church nor state, sovereign nor subjects; but was covetous, ambitious, rebellious, injurious. Yet he was twice lord treasurer, once chancellor, and once sent ambassador to Bavaria. He died A.D. 1340. Such as wish to be merry,' continues Fuller, 'may read the pleasant story of his apparition being condemned after death to be viridis viridarius - a green forester.' In his Church History, Fuller gives this pleasant story: This Burgwash was he who, by mere might, against all right and reason, took in the common land of many poor people (without making the least reparation), therewith to complete his park at Tinghurst (Fingest). These wronged persons, though seeing their own bread, beef, and mutton turned into the bishop's venison, durst not contest with him who was Chancellor of England, though he had neither law nor equity in his proceeding. He persisted in this cruel act of injustice even to the day of his death; but having brought on himself the hatred and maledictions of the poor, he could not rest quietly in his grave; for his spirit was doomed to wander about that land which he had, while living, so unjustly appropriated to himself. It so happened, however, as we are gravely informed by his biographer, that on a certain night he appeared to one of his former familiar friends, apparelled like a forester, all in green, with a bow and quiver, and a bugle-horn hanging by his side. To this gentleman he made known his miserable case. He said, that on account of the injuries he had done the poor while living, he was now compelled to be the park-keeper of that place which he had so wrongfully enclosed. He therefore entreated his friend to repair to the canons of Lincoln, and in his name to request them to have the bishop's park reduced to its former extent, and to restore to the poor the land which he had taken from them. His friend duly carried his message to the canons, who, with equal readiness, complied with their dead bishop's ghostly request, and deputed one of their prebendaries, 'William Bachelor, to see the restoration properly effected. The bishop's park was reduced, and the common restored to its former dimensions; and the ghostly parkkeeper was no more seen. VAUXHALLThe public garden of London, in the reigns of James I and Charles I, was a royal one, or what had been so, between Charing Cross and St. James's Park. From a playfully contrived water-work, which, on being unguardedly pressed by the foot, sprinkled the bystanders, it was called Spring Garden. There was bowling there, promenading, eating and drinking, and, in consequence of the last, occasional quarrelling and fighting; so at last the permission for the public to use Spring Garden was withdrawn. During the Commonwealth, Mulberry Garden, where Buckingham Palace is now situated, was for a time a similar resort. Immediately after the Restoration, a piece of ground in Lambeth, opposite Millbank, was appropriated as a public garden for amusements and recreation; which character it was destined to support for nearly two centuries. From a manor called Fulke's Hall, the residence of Fulke de Breaute, the mercenary follower of King John, came the name so long familiarized to the ears of Londoners-Vauxhall. Pepys, writing on the 28th of May 1667, says - 'By water to Fox-hall, and there walked in the Spring Gardens [the name of the old garden had been transferred to this new one]. A great deal of company, and the weather and garden pleasant; and it is very cheap going thither, for a man may spend what he will or nothing, all as one. But to hear the nightingale and the birds, and here fiddles and there a harp, and here a jew's trump and there laughing, and there fine people walking, is mighty divertising.' The repeated references to Vauxhall, in the writings of the comic dramatists of the ensuing age, fully show how well these divertisements continued to be appreciated.  Through a large part of the eighteenth century, Vauxhall was in the management of a man who necessarily on that account became very noted, Jonathan Tyers. On the 29th of May 1786, a jubilee night celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of his management, being after all somewhat within the truth, as in reality he had opened the gardens in 1732. On that occasion, there was an entertainment called a Ridotto al fresco, at which two-thirds of the company appeared in masks and dominoes, a hundred soldiers standing on guard at the gates to maintain order. Tyers went to a great expense in decorating the gardens with paintings by Hogarth, Hayman, and other eminent artists; and having, by a judicious outlay, succeeded in realizing a large fortune, he retired to a country seat known as Denbighs, in the beautiful valley of the Mole. Here he amused himself by constructing a very extraordinary garden, for his own recreation. The peculiarly eccentric tastes-as regards house and garden decorations-of retired caterers for public amusements, such as showmen and exhibitors of various kinds, are pretty well known; but few ever designed a garden like that of Tyers. One of its ornaments was a representation of the Valley of the Shadow of Death, thus described by Mr. Hughson: 'Awful and tremendous the view, on a descent into this gloomy vale! There was a large alcove, divided into two compartments, in one of which the unbeliever was represented dying in great agony. Near him were his books, which had encouraged him in his libertine course, such as Hobbes, Tindal, &c. In the other was the Christian, represented in a placid and serene state, prepared for the mansions of the blest!' After the death of Jonathan Tyers, his son succeeded to the proprietorship of Vauxhall; he was the friend of Johnson, and is frequently mentioned by Boswell under the familiar designation of Tom Tyers. In a Description of Vauxhall, many times published during the last century, we read the following account of what was called the Dark Walk: 'It is very agreeable to all whose minds are adapted to contemplation and scenes devoted to solitude, and the votaries that court her shrine; and it must be confessed that there is something in the amiable simplicity of unadorned nature, that spreads over the mind a more noble sort of tranquillity, and a greater sensation of pleasure, than can be received from the nicer scenes of art. How simple nature's hand, with noble grace, Diffuses artless beauties o'er the place. 'This walk in the evening is dark, which renders it more agreeable to those minds who love to enjoy the full scope of imagination, to listen to the orchestra, and view the lamps glittering through the trees.' This is all very fine and flowery, but the medal has its reverse; and the newspapers of 1759 speak of the loose persons of both sexes who frequented the Dark Walk, yelling 'in sounds fully as terrific as the imagined horrors of Cavalcanti's bloodhounds;' they further state that ladies were sometimes forcibly driven from their friends into those dark recesses, where dangerous terrors were wantonly inflicted upon them. In 1763, the licensing magistrates bound the proprietors to do away with the dark walks, and to provide a sufficient number of watchmen to keep the peace. The following extract, from a poem published in 1773, does not speak favourably of the company that used to visit the gardens at that time. Such is Vauxhall- For certain every knave that's willing, May get admittance for a shilling; And since Dan Tyers doth none prohibit, But rather seems to strip each gibbet, His clean-swept, dirty, boxing place, There is no wonder that the thief Comes here to steal a handkerchief; For had you, Tyers, each jail ransacked, Or issued an insolvent act, Inviting debtors, lords, and thieves, To sup beneath your smoke-dried leaves,- And then each knave to kindly cram With fusty chickens, tarts, and ham,- You had not made such a collection, For your disgrace and my selection. Horace Walpole, writing in 1750, gives a lively account of the frolics of a fashionable party at these gardens in the June of that year. I had a card from Lady Caroline Petersham, to go with her to Vauxhall. I went accordingly to her house, and found her and the little Ashe, or the Pollard Ashe, as they call her; they had just finished their last layer of red, and looked as handsome as crimson could make them. . . We marched to our barge, with a boat of French horns attending, and little Ashe singing. We paraded some time up the river, and at last debarked at Vauxhall. . . Here we picked up Lord Granby, arrived very drunk from Jenny's Whim [a tavern]. . . At last we assembled in our booth, Lady Caroline in the front, with the visor of her hat erect, and looking gloriously handsome. She had fetched my brother Orford from the next box, where he was enjoying himself with his petite partie, to help us to mince chickens. We minced seven chickens into a china dish, which Lady Caroline stewed over a lamp, with three pats of butter and a flagon of water-stirring, and rattling, and laughing; and we every minute expecting the dish to fly about our ears. She had brought Betty the fruitgirl, with hampers of strawberries and cherries, from Rogers's; and made her wait upon us, and then made her sup by herself at a little table. . . In short, the air of our party was sufficient, as you will easily imagine, to take up the whole attention of the gardens; so much so, that from eleven o'clock to half an hour after one, we had the whole concourse round our booth; at last they came into the little gardens of each booth on the sides of ours, till Harry Vane took up a bumper and drank their healths, and was proceeding to treat them with still greater freedoms. It was three o'clock before we got home. Innumerable jokes used to be passed on the smallness of the chickens, and the exceeding thinness of the slices of ham, supplied to the company at Vauxhall. It has been said that the person who cut the meat was so dexterous from long practice, that he could cover the whole eleven acres of the gardens with slices from one ham. However that may be, the writer well remembers the peculiar manner in which the waiters carried the plates, to prevent the thin shavings of ham from being blown away! The Connoisseur, in 1755, gives the following amusing account of a penurious citizen's reflections on a dish of ham at Vauxhall: 'When it was brought, our honest friend twirled the dish about three or four times, and surveyed it with a settled countenance. Then, taking up a slice of the ham on the point of his fork, and dangling it to and fro, he asked the waiter how much there was of it. 'A shilling's worth, sir,' said the fellow. 'Prithee,' said the cit, 'how much dost think it weighs? ' 'An ounce, sir.' 'Ah! a shilling an ounce, that is sixteen shillings per pound; a reasonable profit, truly! Let me see. Suppose, now, the whole ham weighs thirty pounds: at a shilling per ounce, that is sixteen shillings per pound. Why, your master makes exactly twenty-four pounds off every ham; and if he buys them at the best hand, and salts and cures them himself, they don't stand him in ten shillings a-piece!'' In the British Magazine for August 1782, there is a description of what may be termed a royal scene at Vauxhall. It states: The Prince of Wales was at Vauxhall, and spent a considerable part of the evening in comfort with a set of gay friends; but when the music was over, being discovered by the company, he was so surrounded, crushed, pursued, and overcome, that he was under the necessity of making a hasty retreat. The ladies followed the prince-the gentlemen pursued the ladies-the curious ran to see what was the matter-the mischievous ran to increase the tumult-and in two minutes the boxes were deserted; the lame were overthrown-the well-dressed were demolished-and for half an hour the whole company were contracted in one narrow channel, and borne along with the rapidity of a torrent, to the infinite danger of powdered locks, painted cheeks, and crazy constitutions. Mainly owing to the constant patronage of the Prince of Wales, Vauxhall was a place of fashionable resort all through his time. Nor were the proprietors ungrateful to the prince. In 1791, they built a new gallery in his honour, and deco-rated it with a transparency of an allegorical and most extraordinary character. It represented the prince in armour, leaning against a horse, which was held by Britannia. Minerva held his helmet, while Providence was engaged in fixing on his spurs. Fame, above, blowing a trumpet, and crowning him with laurels! AN ARTIFICIAL MEMORYJohn Bruen, of Stapleford, in Cheshire, who died in 1625, was a man of considerable fortune, who had received his education at Alban Hall, in the University of Oxford. Though he was of Puritan principles, he was no slave to the narrow bigotry of a sect. Hospitable, generous, and charitable, he was beloved and admired by men of all persuasions. He was conscientiously punctual in all the public and private duties of religion, and divinity was his constant study and delight. He was a great frequenter of the public sermons of his times, called prophecyings; and it was his invariable practice to commit the substance of all that he heard to writing. The old adage of 'like master, like man,' was fully verified in the instance of Bruen's servant, one Robert Pasfield, who was equally as fond of sermons as his master, but though 'mighty in the Scriptures,' could neither read nor write. So, for the help of his memory, he invented and framed a girdle of leather, long and large, which went twice about him. This he divided into several parts, allotting each book in the Bible, in its order, to one of these divisions; then, for the chapters, he affixed points or thongs of leather to the several divisions, and made knots by fives and tens thereupon to distinguish the chapters of each book; and by other points he divided the chapters into their particular contents or verses. This he used, instead of pen and ink, to take notes of sermons; and made so good use of it, that when he came home from the conventicle, he could repeat the sermon through all its several heads, and quote the various texts mentioned in it, to his own great comfort, and the benefit of others. This girdle Mr. Bruen kept, after Pasfield's decease, in his study, and would often merrily call it the Girdle of Verity. |