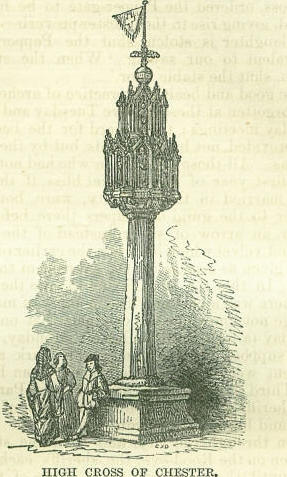

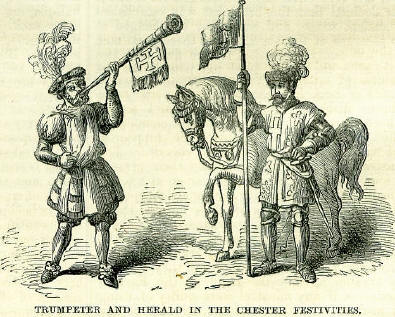

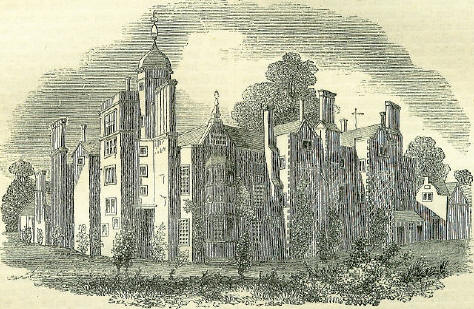

28th MarchBorn: Sir Thomas Smith, author of The English Commonwealth, 1514-15, Saffron Walden; Dr. Andrew Kippis, Nonconformist divine, editor of Biographia Britannica, 1725, Nottingham. Died: Pope Martin IV, 1285; Lord Fitzwalter, and Lord John de Clifford, killed at Feraybridge, 1461; Sanzio Raffaelle, painter, 1520, Rome; Jacques Callot, eminent engraver, 1636, Nanci; Wentzel Hollar, celebrated engraver, 1677, Westminster; Margaret Woffington, celebrated actress, 1760; Dr. James Tunstall, vicar of Rochdale, 1772; Marquis de Condorcet, philosophical writer, 1794; General Sir Ralph Abercrombie, battle of Alexandria, 1801; Henry Hase, Bank of England, 1829; Rev. Dr. Valpy, classical scholar, Reading, 1836; Thomas Morton, dramatist, 1838. Feast Day: Saints Priscus, Malchus, and Alexander, of Caesarea, in Palestine, martyrs, 280. St. Sixtus III, Pope, 440. St. Gontran, King of Burgundy, 593. EASTER FESTIVITIES IN CHESTERMost people are aware how much of a mediaeval character still pertains to the city of Chester, -how its gable-fronted houses, its 'Rows' (covered walks over the groundfloors), and its castellated town walls, combine to give it an antique character wholly unique in England. It is also well known how, in the age succeeding the Conquest, this city was the seat of the despotic military government of Hugh d'Avranches, commonly called, from his savage character, Hugo Lupus, whose sword is still preserved in the British Museum. Chester was endowed by Hugo with two yearly fairs, at Midsummer and Michaelmas, on which occasions criminals had free shelter in it for a month, as indicated by a glove hung out at St. Peter's Church,-for gloves were a manufacture at Chester. It was on these occasions that the celebrated Chester mysteries, or scriptural plays, were performed.  As the tourist walks from the Watergate along the ancient walls towards the Cathedral, he cannot fail to notice the beautiful meadow lying between him and the river; it is the Rood-eye, or as formerly written, the Roodee; the scene of the sports for which Chester was so long famous, eye being a term used for a waterside meadow; and the legend of the rood or cross was the following:--A cross was erected at Hawarden, by which a man was unfortunately killed; and in accordance with the superstition of those days, the cross was made to bear the blame of the accident, and was thrown into the river; for which sacrilegious act the men received the name of Hárden Jews. Floated down the stream, it was taken up at the Rood-eye, and became very celebrated for the number of miracles it wrought. Sad to relate, after the Reformation it again became the subject of scorn and contempt; for the master of the grammar-school converted it into a block on which to chastise his refractory pupils, and it was finally burnt, perhaps by the very scholars who had suffered on it. We need not wonder that in so ancient and thriving a city old customs and games were well kept up; and to begin with those of the great festival of Easter. Then might be seen the mayor and corporation, with the twenty guilds established in Chester, with their wardens at their heads, setting forth in all their pageantry to the Rood-eye to play at football. The mayor, with his mace, sword, and cap of maintenance, stood before the cross, whilst the guild of Shoe-makers, to whom the right had belonged from time immemorial, presented him with the ball of the value of ' three and four pence or above,' and all set to work right merrily. But, as too often falls out in this game, 'greate strife did arise among the younge persons of the same cittie,' and hence, in the time of Henry the Eighth, this piece of homage to the mayor was converted into a present from the shoemakers to the drapers of six gleaves or hand-darts of silver, to be given for the best foot-race; whilst the saddlers, who went in procession on horseback, attired in all their bravery, each carrying a spear with a wooden ball, decorated with flowers and arms, exchanged their offering for a silver bell, which should be a 'rewarde for that horse which with speedy runninge should run before all others.' It would appear that the women were not banished from a share in the sports, but had their own football match in a quiet sort of way; for as the mayor's daughter was engaged with other maidens in the Pepper-gate at this game, her lover, knowing well that the father was too busy on the Rood-eye with the important part he had to play at these festivities, entered by the gate and carried off the fair girl,-nothing loth, we may suppose. The angry father, when he discovered the loss, ordered the Pepper-gate to be for ever closed, giving rise to the Chester proverb-' When the daughter is stolen, shut the Pepper-gate;' equivalent to our saying, ' When the steed is stolen, shut the stable door.' The good and healthful practice of archery was not forgotten at these Shrove Tuesday and Easter Monday meetings; the reward for the best shot was provided, not by the guilds, but by the bride-grooms. All those happy men who had not closed their first year of matrimonial bliss, if they had been married in the said city, were bound to deliver to the guild of drapers there before the mayor, an arrow of silver, instead of the ball of silk and velvet which had been the earlier offering, to be given as a prize for the exercise of the long-bow. In this the sheriffs had to take their part, for there was a custom, 'the memory of man now livinge not knowinge the original,' that on Black Monday (a term used for Easter Monday, owing, it is supposed, to the remarkably dark and in-clement weather which happened when Edward the Third lay with his army before Paris) the two sheriffs should shoot for a breakfast of calves' head and bacon. The drum sounded the proclamation through the city, and from the stalwart yeomen on the Rood-eye, the sheriffs each chose one, until they had got the number of twelve-score; the shooting began on one side and then on the other, until the winners were declared; they then walked first, holding their arrows in their hands, whilst the losers followed with their bows only, and marching to the Town Hall took their breakfast together in much loving jollity, 'it being a commendable exercise, a good recreation, and a lovinge assembly;' a remark of the old writer with which our readers will not disagree. But time, which changes all things, led the sheriffs in 1640 to offer a piece of plate to be run for instead of the calves' head breakfast; we may be sure there were some Puritans at work here, but with the Englishman's natural love of good fare, this resolution was rescinded in 1674, and it was decided that the breakfast was established by ancient usage, and could not be changed at the pleasure of the sheriffs; yet these great men were not easily persuaded, for we find that two years after they were fined ten pounds for not keeping the calves' head feast. When the last of these festivities came off; we know not: it is now kept as an annual dinner, but not on any fixed day. The shooting has, alas! disappeared; the care with which they trained their children in this vigorous exercise may be traced from a curious order we find in the common council book, that, 'For the avoiding of idleness, all children of six years old and upwards, shall, on week days, be set to school, or some virtuous labour, whereby they may hereafter get an honest living; and on Sundays and holy days they shall resort to their parish churches and there abide during the time of divine service, and in the afternoon all the said male children shall be exercised in shooting with bows and arrows, for pins and points only; and that their parents furnish them with bows and arrows, pins and points, for that purpose, according to the statute lately made for maintenance of shooting in long bows and artillery, being the ancient defence of the kingdom.' If we walk through the streets of the city on this festive Easter Monday, we shall probably see a crowd of young and gay gallants carrying about a chair, lined with rich white silk, from which garlands of flowers and streamers of ribbon depend; as they meet each fair damsel, she is requested to seat herself in the chair, no opposition being allowed, nor may we suppose, in those times of free and easy manners, that any would he offered. The chair is then lifted as high as the young men can poise it in the air, and on its descent a kiss is demanded by each, and a fee must be also paid. It would seem that this custom called 'lifting' still prevails in the counties of Cheshire, Lancashire, Shropshire, and Warwickshire, but is confined to the streets; formerly they entered the houses, and made every inmate undergo the lifting. The late Mr. Lysons, keeper of the records of the Tower of London, gave an extract from one of the rolls in his custody to the Society of Antiquaries, which mentioned a payment to certain ladies and maids of honour for taking King Edward the First in his bed, and lifting him; so it appears that no rank was exempt. The sum the King paid was no trifle, being equal to about £400 in the present day. The women take their revenge on Easter Tuesday, and go about in the same manner: three times must the luckless Wight be elevated; his escape is in vain, if seen and pursued. Strange to say, the custom is one in memory of the Resurrection, a vulgar and childish absurdity into which so many of the Romish ceremonies denerated. We may be sure that the Pace, Pask, or Easter eggs were not forgotten by the Chester children. Eggs were in such demand at that season that they always rose considerably in price; they were boiled very hard in water coloured with red, blue, or violet dyes, with inscriptions or landscapes traced upon them; these were offered as presents among the 'valentines' of the year, but more frequently played with by the boys as balls, for ball-playing on Easter Monday was universal in every rank. Even the clergy could not forego its delights, and made this game a part of their service. Bishops and deans took the ball into the church, and at the commencement of the anti-phone began to dance, throwing the ball to the choristers, who handed it to each other during the time of the dancing and antiphone. All then retired for refreshment: a gammon of bacon eaten in abhorrence of the Jews was a standard dish; with a tansy pudding, symbolical of the bitter herbs commanded at the paschal feast. An old verse commemorates these customs: At stool-ball, Lucia, let as play, For sugar, cakes, or wine; Or for a tansy let us pay, The loss be thine or mine. If thou, my dear, a winner be At trundling of the ball, The wager thou shalt have, and me, And my misfortunes all. The churches were adorned at this season like theatres, and crowds poured in to see the sepulchres which were erected, representing the whole scene of our Saviour's entombment. A general belief prevailed in those days that our Lord's second coming would be on Easter Eve; hence the sepulchres were watched through the night, until three in the morning, when two of the oldest monks would enter and take out a beautiful image of the Resurrection, which was elevated before the adoring worshippers during the singing of the anthem, 'Christus resurgens.' It was then carried to the high altar, and a procession being formed, a canopy of velvet was borne over it by ancient gentlemen: they proceeded round the exterior of the church by the light of torches, all singing, rejoicing, and praying, until coming again to the high altar it was there placed to remain until Ascension-day. In many places the monks personated all the characters connected with the event they celebrated, and thus rendered the scene still more theatrical.  Another peculiar ceremony belonging to Chester refers to the minstrels being obliged to appear yearly before the Lord of Dutton. In those days when the monasteries, convents, and castles were but dull abodes, the insecurity of the country and the badness of the roads making locomotion next to impossible, the minstrels were most accept-able company 'to drive dull care away,' and were equally welcomed by burgher and noble. They generally travelled in bands, sometimes as Saxon gleemen, sometimes having instrumentalists joined to the party, as a tabourer, a bagpiper, dancers, and jugglers. At every fair, feast, or wedding, the minstrels were sure to be; arrayed in the fanciful dress prevailing during the reigns of the earls Norman kings-mantles and tunics, the latter having tight sleeves to the wrist, but terminating in a long depending streamer which hung as low as the knees; a hood or flat sort of Scotch cap was the general head-dress, and the legs were enveloped in tight bandages, called chausses, with the most absurd peak-toed boots and shoes, some being intended to imitate a ram's horn or a scorpion's tail. In all the old books of household expenses, we meet with the largesses which were given to the minstrels, varying, of course, according to the riches and liberality of the donor: thus when the Queen of Edward I was confined of the first Prince of Wales in Carnarvon Castle, the sum of £10 was given to the minstrels (Welsh harpers, we may suppose them to have been) on the day of her churching. In another old record of the brotherhood feasts at Abingdon, we find them much more richly rewarded than the priests themselves; for whilst twelve of the latter got fourpence each for singing a dirge, twelve minstrels had two-and-threepence each, food for themselves and their horses, to make the guests merry: wise people were they, and knew the value of a good laugh during the process of digestion. It was customary for the minstrels of certain districts to be under the protection of some noble lord, from whom they received a license at the holding of an annual court; thus the Earls of Lancaster had one at Tutbury, on the 16th of August, when a king of the minstrels and four stewards were chosen: any offenders against the rules of the society were tried, and all complaints brought before a regular jury. This jurisdiction belonged in Chester to the very ancient family of the Duttons, who took their name from a small townsPeterhip near Frodshaw, which was purchased for a coat of mail and a charger, a palfrey and a sparrowhawk, by Hugh the grandson of Odard, son of Ivron, Viscount of Constantine, one of William the Conqueror's Norman knights. Nor did the Duttons soon lose the warlike character of their race, for we find them long after joining in any rebellion or foray that the licentious character of the times permitted. Harry Hotspur inveigled , the eleventh knight, to join him in his ill-fated expedition; happily, however, the king pardoned him. Much more unfortunate were they at Bloreheath; at that battle Sir Peter's grandson, Sir Thomas, was killed, with his brother and eldest son. The way in which they gained the jurisdiction over the Cheshire minstrels was characteristic. We have previously mentioned the extraordinary privilege granted of exemption from punishment during the Chester fairs, a privilege which could not fail in those days to draw together a large concourse of lawless and ruffianly people. During one of these fairs, Ranulph de Blundeville, Earl of Chester, was besieged in his Castle of Rhuddlan, by the yet unsubdued Welsh; when the news of this reached the ears of John Lacy, constable of Chester, he called together the minstrels who were present at the fair, and with their assistance collected a large number of disorderly people, armed but indifferently with whatever might be at hand, and sent them off under the command of Hugh Dutton, in the hope of effecting some relief for the Earl. When they arrived in sight of the castle their numbers had a highly imposing appearance; and the Welsh, taking them for the regular army, and not waiting to try their discipline, or discover their lack of arms, immediately raised the siege, and marched back to their own fastnesses, leaving the Earl full of gratitude to his deliverers; as a token of which, he gave to their captain jurisdiction over the minstrels for ever. This, then, was the origin of the grand procession which took place yearly on St. John the Baptist's day, and was continued for centuries, being only laid aside in the year 1756. In the fine old Eastgate Street, the minstrels assembled, the lord of Dutton or his heir giving them the meeting. His banner or pennon waved from the window of the hostelry where he took up his abode, and where the court was to be held; a drummer being sent round the town to collect the people, and inform them at what time he would meet them. At eleven o'clock a procession was formed: a chosen number of their instrumentalists formed themselves into a band and walked first; two trumpeters in their gorgeous attire followed, blowing their martial strains; the remainder of the minstrels succeeded, white napkins hung across their shoulders, and the principal man carried their banner. After these came the higher ranks, the Lord of Dutton's steward bearing his token of office, a white wand; the tabarder, or herald, his short gown, from which he derived his name, being emblazoned with the Dutton arms; then the Lord of Dutton himself, the object of all this homage, accompanied by many of the gentry of the city and neighbourhood-and Cheshire can number more ancient families than any other county in England; of whom old Fuller tells us: They are remarkable on a fourfold account: their numerousness, not to be paralleled in England in the like extent of round; their antiquity, many of their ancestors being fixed here before the Norman conquest; their loyalty; and their hospitality.' Thus they moved forward to the church of St. John the Baptist, the which having entered, the musicians fell upon their knees, and played several pieces of sacred music in this reverent attitude; the canons and vicars choral then performed divine service, and a proclamation was made, 'God save the King, the Queen, the Prince, and all the Royal family; and the honourable Sir Peter Dutton, long may he live and support the honour of the minstrel court.' The procession returned as it came, and then entered upon the important business of satisfying the appetite with the fine rounds of beef, haunches of venison, and more delicate dishes of peacock, swan, and fowls; followed by those wondrous sweet compounds called `subtleties,' with stout, ale, hippocras, and wine, to make every heart cheerful. The minstrels did not forget to make their present of four flagons of wine, and a lance, as a token of fealty to their lord, with the sum of fourpencehalfpenny for the licence which he granted them, and in which they were commanded 'to behave themselves lively as a licensed minstrel of the court ought to do.' The jury were empannelled during the afternoon, to inquire if they knew of any treason against the King or the Earl of Chester, or if any minstrel were guilty of using his instrument without licence, or had in any way misdemeaned himself; the verdicts were pronounced, the oaths administered, and all separated, looking forward to their next merry meeting. EASTER SINGERS IN THE VORARLBERGIf there be any country which has hitherto escaped the invasion of civilization and a revolution in manners, it is assuredly the Vorarlberg in the Tyrol. This primitive region begins where the ordinary traveller stops, wearied with the beauties of Switzerland and hesitating whether he should abandon the high roads to rough it in the difficult passes of these mountains. At Rochach the steamer leaves Switzerland and five times changes its flag on Lake Constance before reaching Bregentz, where the two-headed eagle announces to the traveller that he has set foot in Austrian territory. There he disembarks, and after passing through the formalities of the custom-house and passport office, he can go about, act, and talk with the greatest freedom, delivered from the fear of any espionage even on the part of the gens-d'armes of his Apostolic Majesty, the Emperor Francis Joseph. It is only for the last twelve years that the inhabitants have had to submit to a police, who are looked upon with an evil eye by these free mountaineers; they say that it is not required by reason of the tranquillity of the country, no robbery or assassination having ever been committed.  About a league from Lake Constance the mountains assume a wild and savage character; a narrow defile leads to a high hill which must be crossed to reach the valley of Schwartzenberg. I gained the summit of the peak at sunset; the rosy vapour which surrounded it hid the line of the horizon, and gave to the lake the appearance of a sea; the Rhine flowed through the bottom of the valley and emptied itself into the lake, to recommence its course twelve leagues farther on. On one side were the Swiss mountains; opposite was Landau, built on an island; on the other side the dark forests of Wurtemberg, and over the side of the hill the chain of the Vorarlberg mountains. The last rays of the setting sun gilded the crests of the glaciers, whilst the valleys were already bathed in the soft moonlight. From this high point the sounds of the bells ringing in the numerous villages scattered over the mountains were distinctly heard, the flocks were being brought home to be housed for the night, and everywhere were sounds of rejoicing. 'It is the evening of Holy Saturday,' said our guide; 'the Tyrolese keep the festival of Easter with every ceremony.' And so it was; civilization has passed that land by and not left a trace of its unbelieving touch; the resurrection of Christ is still for them the tangible proof of revelation, and they honour the season accordingly. Bands of musicians, for which the Tyrolese have always been noted, traverse every valley, singing the beautiful Easter hymns to their guitars; calling out the people to their doors, who join them in the choruses and together rejoice on this glad anniversary. Their wide-brimmed Spanish hats are decorated with bouquets of flowers; crowds of children accompany them, and when the darkness of night comes on, bear lighted torches of the pine wood, which throw grotesque wooden huts. The Pasch or Paschal eggs, which shadows over the spectators and picturesque have formed a necessary part of all Easter offerings for centuries past, are not forgotten: some are dyed in the brightest colours and boiled hard; others have suitable mottoes written on the shells, and made ineffaceable by a rustic process of chemistry. The good wife has these ready prepared, and when the children bring their baskets they are freely given: at the higher class of farmers' houses wine is brought out as well as eggs, and the singers are refreshed and regaled in return for their Easter carols. WENTZEL HOLLARWentzel Hollar, an eminent engraver, and scion of an ancient Bohemian family, was born at Prague in 1607. His parents destined him for the profession of the law, but his family being ruined and driven into exile by the siege and capture of Prague, he was compelled to support himself by a taste and ability, which he had very early exhibited, in the use of the pen and pencil. In 1636, Thomas Earl of Arundel, an accomplished connoisseur, when passing through Frankfort, on his way to Vienna, as Ambassador to the Emperor Frederick II, met Hollar, and was so pleased with the unassuming manner and talent of the young engraver, that he attached him to the suit of the embassy. On his return to England, the earl introduced Hollar to Charles the First, and procured him the appointment of drawing-master to the young prince, subsequently Charles the Second. For a short period all went well with Hollar, for he now enjoyed the one fitful gleam of sunshine which illumined his toil-worn life. He resided in apartments in Arundel House, and was constantly employed by his noble patron, in engraving those treasures of ancient art still known as the Arundelian Marbles. But soon the great civil war broke forth; Lord Arundel was compelled to seek a refuge on the Continent, while Hollar, with two other artists, Peake and Faithorne, accepted commissions in the King's service. All three, under the command of the heroic Marquis of Winchester, sustained the memorable protracted siege in Basing House, and though most of the survivors were put to the sword by the parliamentary party, yet, through some means now unknown, the lives of the artists were spared. When he regained his liberty, Hollar followed his patron to Antwerp, and resumed his usual employment; but the early death of Lord Arundel compelled him to return to England, and earn a precarious subsistence by working for print-dealers. His patient industry anticipated a certain reward at the Restoration; but when that event occurred, he found himself as much neglected as the generality of the expectant Royalists were. A fallacious prospect of advantage was opened to him in 1669. He was appointed by the Court to proceed to Tangier, and make plans and drawings of the fortifications and principal buildings there. On his return, the vessel in which he sailed was attacked by seven Algerine pirates, and after a most desperate conflict, the pirates, ship succeeded in gaining the protection of the port of Cadiz, with a loss of eleven killed and seventeen wounded. Hollar, during the engagement, coolly employed himself in sketching the exciting scene, an engraving of which he afterwards published. For a year's hard work, under an African sun, poor Hollar received no more than one hundred pounds and the barren title of the King's Iconographer. His life now became a mere struggle for bread. The price he received for his work was so utterly inadequate to the extraordinary care and labour he bestowed upon it, that he could scarcely earn a bare subsistence. He worked for fourpence an hour, with an hour-glass always before him, and was so scrupulously exact with respect to his employer's time, that at the least interruption, he used to turn the glass on its side to prevent the sand from running. Hollar was not what may be termed a great artist. His works, though characterised by a truthful air of exactness, are deficient in picturesque effect; but he is the engraver whose memory is ever faithfully cherished by all persons of antiquarian predilections. Hundreds of ancient monuments, buildings, costumes, ceremonies, are preserved in his works, that, had they not been engraved by his skilful hand, would have been irretrievably lost in oblivion. He died as poor as he had lived. An execution was put into his house as he lay dying. With characteristic meekness, he begged the bailiff's forbearance, praying that his bed might be left for him to die on; and that he might not be re-moved to any other prison than the grave. And thus died Hollar, a man possessed of a singular ability, which he exercised with an industry that permitted neither interval nor repose for more than fifty years. He is said to have engraved no less than 24,000 plates. Of a strictly moral character, unblemished by the failings of many men of genius, and of unceasing industry, he passed a long life in adversity, and ended it in destitution of common comfort. Yet of no en-graver of his age is the fame now greater, or the value of his works enhanced to so high a degree. TRIAL OF FATHER GARNETOn the 28th of March 1606, took place the trial of Father Garnet, chief of the Jesuits in England, for his alleged concern in the Gun-powder Treason. He was a man of distinguished ability and zeal for the interests of the Romish Church, and had been consulted by the conspirators Greenway and Catesby regarding the plot, on an evident understanding that he was favourable to it. Being found guilty, he was condemned to be hanged, which sentence was put in execution on the ensuing 3rd of May, in St. Paul's-churchyard. There has ever since raged a controversy about his criminality; but an impartial person of our day can scarcely but admit that Garnet was all but actively engaged in forwarding the conspiracy. He himself acknowledged that he was consulted by two of the plotters, and that he ought to have revealed what he knew. At the same time, one must acknowledge that the severities then practised towards the professors of the Catholic faith were calculated in no small measure to confound the sense of right and wrong in matters between them and their Protestant brethren. PRIESTS' HIDING CHAMBERSDuring a hundred and fifty years following the Reformation, Catholicism, as is well known, was generally treated by the law with great severity, insomuch that a trafficking priest found in England was liable to capital punishment for merely performing the rites of his religion. Nevertheless, even in the most rigorous times, there was always a number of priests concealed in the houses of the Catholic nobility and gentry, daring everything for the sake of what they thought their duty. The country-houses of the wealthy Catholics were in many instances provided with secret chambers, in which the priests lived concealed probably from all but the lord and lady of the mansion, and at the utmost one or two confidential domestics. It is to be presumed that a priest was rarely a permanent tenant of the Patmos provided for him, because usually these concealed apartments were so straitened and inconvenient that not even religious enthusiasm could reconcile any one long to occupy them. Yet we are made aware of an instance of a priest named Father Blackhall residing for a long series of years in the reign of Charles I concealed in the house of the Viscountess Melgum, in the valley of the Dee, in Scotland. As an example of the style of accommodation, two small chambers in the roof formed the priest's retreat in the old half-timber house of liar-borough Hall, midway between Hegley and Kidderminster. At Watcomb, in Berks, there is an old manor-house, in which the priest's chamber is accessible by lifting a board on the staircase. A similar arrangement existed at Dinton Nall, near Aylesbury, the seat of Judge Mayne, one of the Regicides, to whom it gave temporary shelter at the crisis of the Restoration. It was at the top of the mansion, under the beams of the roof, and was reached by a narrow passage lined with cloth. Not till three of the steps of an ordinary stair were lifted up, could one discover the entrance to this passage, along which Mayne could crawl or pull himself in order to reach his den. Captain Duthy, in his Sketches of Hampshire, notices an example which existed in that part of England, In the old mansion of Woodcotc, he says, 'behind a stack of chimneys, accessible only by removing the floor boards, was an apartment which contained a concealed closet . . . a priest's hole.' The arrangements thus indicated give a striking idea of the dangers which beset the ministers of the Romish faith in times when England lived in continual apprehension of changes which they might bring about, and when they were accordingly treated with all the severity due to public enemies.  One of the houses most remarkable for its means of concealing proscribed priests was Hendlip Hall, a spacious mansion situated about four miles from Worcester, supposed to have been built late in Elizabeth's reign by John Abingdon, the queen's cofferer, a zealous partisan of Mary Queen of Scots. It is believed that Thomas Abingdon, the son of the builder of the mansion, was the person who took the chief trouble in so fitting it up. The result of his labours was that there was scarcely an apartment which had not secret ways of going in and out. Some had back staircases concealed in the walls; others had places of retreat in their chimneys; some had trap-doors, descending into hidden recesses. All,' in the language of a writer who examined the house, 'presented a picture of gloom, insecurity, and suspicion.' Standing, moreover, on elevated ground, the house afforded the means of keeping a watchful look-out for the approach of the emissaries of the law, or of persons by whom it might have been dangerous for any skulking priest to be seen, supposing his reverence to have gone forth for an hour to take the air. Father Garnet, who suffered for his guilty knowledge of the Gunpowder Treason, was concealed in Hendlip, under care of Mr. and Mrs. Abingdon, for several weeks, in the winter of 1605-6. Suspicion did not light upon his name at first, but the confession of Catesby's servant, Bates, at length made the government aware of his guilt. He was by this time living at Hendlip, along with a lady named Anne Vaux, who devoted herself to him through a purely religious feeling, and another Jesuit, named Hall. Just as we have surmised regarding the general life of the skulking priesthood, these persons spent most of their hours in the apartments occupied by the family, only resorting to places of strict concealment when strangers visited the house. When Father Garnet came to be inquired after, the government, suspecting Hendlip to be his place of retreat, sent Sir Henry Bromley thither, with instructions which reveal to us much of the character of the arrangements for the concealment of priests in England. 'In the search,' says this document, 'first observe the parlour where they use to dine and sup; in the east part of that parlour it is conceived there is some vault, which to discover you must take care to draw down the wainscot, whereby the entry into the vault may be discovered. The lower parts of the house must be tried with a broach, by putting the same into the ground some foot or two, to try whether there may be perceived some timber, which, if there be, there must be some vault underneath it. For the upper rooms, you must observe whether they be more in breadth than the lower rooms, and look in which places the rooms be enlarged; by pulling up some boards, you may discover some vaults. Also, if it appear that there be some corners to the chimneys, and the same boarded, if the boards be taken away there will appear some. If the walls seem to be thick, and covered with wainscot, being tried with a gimlet, if it strike not the wall, but go through, some suspicion is to be had thereof. If there be any double loft, some two or three feet, one above another, in such places any may be harboured privately. Also, if there be a loft towards the roof of the house, in which there appears no entrance out of any other place or lodging, it must of necessity be opened and looked into, for these be ordinary places of hovering [hiding].' Sir Henry invested the house, and searched it from garret to cellar, without discovering anything suspicious but some books, such as scholarly men might have been supposed to use. Mrs. Abingdon-who, by the way, is thought to have been the person who wrote the letter to Lord Monteagle, warning him of the plot-denied all knowledge of the person searched for. So did her husband when he came home. 'I did never hear so impudent liars as I find here,' says Sir Henry in his report to the Earl of Salisbury, forgetting how the power and the habit of mendacity was acquired by this persecuted body of Christians. After four days of search, two men came forth half dead with hunger, and proved to be servants. Sir Henry occupied the house for several days more, almost in despair of further discoveries, when the confession of a conspirator condemned at Worcester put him on the scent for Father Hall, as for certain lying at Hendlip. It was only after a search protracted to ten days in all, that he was gratified by the voluntary surrender of both Hall and Garnet. They came forth from their concealment, pressed by the need for air rather than food, for marmalade and other sweetmeats were found in their den, and they had had warm and nutritive drinks passed to them by a reed 'through a little hole in a chimney that backed another chimney, into a gentlewoman's chamber.' They had suffered extremely by the smallness of their place of concealment, being scarcely able to enjoy in it any movement for their limbs, which accordingly became much swollen. Garnet expressed his belief that, if they could have had relief from the blockade for but half a day, so as to allow of their sending away books and furniture by which the place was hampered, they might have baffled inquiry for a quarter of a year. |