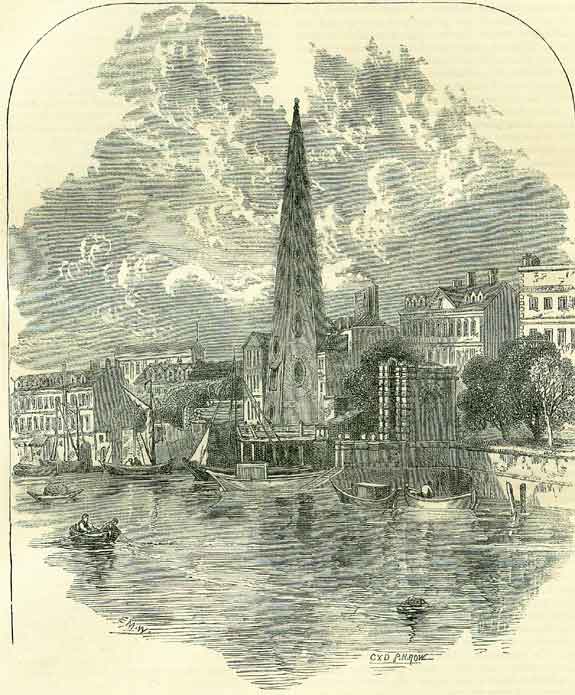

26th MayBorn: Charles Duke of Orleans, 1391; Dr. Michael Ettmuller, eminent German physician, 1644, Leipsig; John Gale, 1680, London; Shute Barrington, Bishop of Durham, 1734. Died: The Venerable Bede, historian, 725, Jarrow, Durham; Samuel Pepys, 1703, Clapham; Thomas Southern, dramatist, 1746; James Burnet, Lord Monboddo, 1799, Edinburgh; Francis Joseph Haydn, musical composer, 1809, Grumpendorff Vienna; Cape Loin, miscellaneous writer, 1821, Moncallier, near Turin; Admiral Sir Sidney Smith, G.C.B., 1840; Jacques Lafitte, eminent French banker and political character, 1844, Paris. Feast Day: St. Quadrates, Bishop of Athens, 2nd century; St. Eleutherius, pope, martyr, 192; St. Augustine, apostle of the English (605?); St. Oduvald, abbot of Melrose, 698; St. Philip Neri, 1595. ST. AUGUSTINEClose upon thirteen hundred years ago, a monk named Gregory belonged to the great convent of St. Andrew, situated on the Coelian Mount, which, rising immediately behind the Colisseum, is so well known to all travellers at Home. Whatever may have been the good or evil of this remarkable man's character is not a fit subject for discussion here. Let it suffice to say, both his panegyrists and detractors agree in stating that he was distinguished among his contemporaries for Christian charity, and a deep interest in the bodily and spiritual welfare of children. One day, as Gregory happened to pass through the slave market at Home, his attention was attracted by an unusual spectacle. Among the crowd of slaves brought from many parts to be sold in the great mart of Italy, there were the ebony-coloured, simple-looking negroes of Africa, the dark, cunning-eyed Greeks, the tawny Syrians and Egyptians-these were the usual sights of the place. But on this eventful occasion Gregory perceived three boys, whose fair, red and white complexions, blue eyes, and flaxen hair, contrasted favourably with the dusky races by whom they were surrounded. Attracted by feelings of benevolent curiosity, the monk asked the slave-dealer from whence had those beautiful but strange-looking children been brought. 'From Britain, where all the people are of a similar complexion,' was the reply. To his next question, respecting their religion, he was told that they were pagans. 'Alas!' rejoined Gregory, with a profound sigh, 'more is the pity that faces so full of light and brightness should be in the hands of the Prince of Darkness; that such grace of outward appearance should accompany minds without the grace of God within.' Asking what was the name of their nation, he was told that they were called Angles, or English. 'Well said,' replied the monk, 'rightly are they called Angles, for they have the faces of angels, and they ought to be fellow-heirs of heaven.' Pursuing his inquiries, he was informed that they were 'Deirans,' from the land of Deira (the land of wild deer), the name then given to the tract of country lying between the rivers Tyne and Humber. 'Well said again,' answered Gregory, 'rightly are they called Deirans, plucked as they are from God's ire (de Ira Dei), and called to the mercy of heaven.' Once more he asked, ' What is the name of the king of that country?' The reply was, 'Ella.' Then said Gregory, 'Allelujah! the praise of God their Creator shall be sung in those parts.' Thus ended the memorable conversation, strangely exhibiting to us the character of Gregory and his age. The mixture of the playful and the serious, the curious distortions of words, which seem to us little more than childish punning, was to him and his contemporaries the most emphatic mode of expressing their own feelings, and instructing others. Nor was it a mere passing interest that the three English slaves had awakened in the mind of the monk; he went at once from the market-place to the Pope, and obtained permission to preach the Gospel to the English people. So, soon after, Gregory, with a small but chosen band of followers, set out from Rome for the far-distant shores of Britain. But on the third day of their journey, as they rested during the noontide heat, a locust leaped upon the book that Gregory was reading; and he then commenced to draw a moral from the act and name of the insect. 'Rightly is it called locusta,' he said, 'because it seems to say to us loco sta - stay in your place. I see that we shall not be able to finish our journey.' And as he spoke couriers arrived, commanding his instant return to Rome, a furious popular tumult having broken out on account of his absence. Years passed away. Gregory became Pope; still affairs of state and politics did not cause him to forget the pagan Angles. At length, learning that one of the Saxon kings had married a Christian princess, he saw that the favourable moment had arrived to put his long-cherished project into execution. Remembering his old convent on the Coelian Mount, he selected Augustine, its prior, and forty of the monks, as missionaries to England. The convent of St Andrew still exists, and in one of its chapels there is yet shown an ancient painting representing the departure of Augustine and his followers. Let us now turn our attention to England. The Saxon Ethelbert, one of the dynasty of the Ashings, or sons of the Ashtree, was then king of Kent, and had also acquired a kind of imperial sway over the other Saxon kings, as far north as the banks of the Humber. To consolidate his power, he had married Bertha, daughter of Caribert, King of Paris. Like all his race, Ethelbert was a heathen; while Bertha, as a descendant of Clovis, was a Christian; and one of the clauses in their marriage contract stipulated that she should enjoy the free exercise of her religion. Accordingly, she brought with her to England one Luidhard, a French bishop, as her chaplain; and she, and a few of her attendants, worshipped in a small building outside of Canterbury, on the site of which now stands the venerable church dedicated to St. Martin. Of all the great saints of the period, the most famous was St. Martin of Tours; and, in every probability, the name, as applied to this church, or the one which preceded it on the same site, was a memorial of the recollections the French princess cherished of her native country and religion while in a land of heathen strangers. Augustine and his companions landed at a place called Ebbe's Fleet, in the island of Thanet. The exact date of this important event is unknown, but the old monkish chroniclers delight in recording that it took place on the very day the great impostor, Mahomet, was born. The actual spot of their landing is still traditionally pointed out, and a farm-house near it still bears the name of Ebbe's Fleet. It must be remembered that Thanet was at that period really an island, being divided from the mainland by an arm of the sea. Augustine selected this spot, thinking he would be safer there than in a closer contiguity to the savage Saxons; and Ethelbert, on his part, wished the Christians to remain for some time in Thanet, lest they might practise magical arts upon him. At length a day was appointed for an interview between the missionary and king. The meeting took place under an ancient oak, that grew on the high land in the centre of Thanet. On one side sat the Saxon son of the Ashtree, surrounded by his fierce pagan warriors; on the other the Italian prior, attended by his peaceful Christian monks and white - robed choristers. Neither understood the language of the other, but Augustine had provided interpreters in France, who spoke both Latin and Saxon, and thus the conversation was carried on. Augustine spoke first; the king listened with attention, and then replied to the following effect: Your words and promises are fair; but as they are new and doubtful, I cannot give my assent to them, and leave the customs I have so long observed with all my race. But as you have come hither strangers from a long distance, and as I seem to myself to have seen clearly that what you yourselves believed to be good you wish to impart to us, we do not wish to molest you; nay, rather we are anxious to receive you hospitably, and to give you all that is needed for your support; nor do we hinder you from joining all whom you can to the faith of your religion.' Augustine and his followers, being then allowed to reside in Canterbury, walked thither in solemn procession, headed by a large silver cross, and a banner on which was painted - rudely enough, no doubt - a representation of the Saviour. And as they marched the choristers sang one of the still famous Gregorian chants, a litany which Gregory had composed when Rome was threatened by the plague, commencing thus: We beseech thee, 0 Lord, in all thy mercy, that thy wrath and thine anger may be removed from this city, and from thy holy house, Allelujah! And thus Gregory's grand wish was fulfilled; the Allelujah was heard in the wild country of Ella, among the pagan people of the Angles, who (as Gregory said, in his punning style) are situated in the extreme angle of the world. On the following Whit Sunday, June 2nd, A.D. 597, Ethelbert was baptized-with the exception of that of Clovis, the most important baptism the world had seen since the conversion of Constantine. The lesser chiefs and common people soon followed the example of their king, and it is said, on the authority of Gregory, that on the following Christmas ten thousand Saxons were baptized in the waters of the Swale, near Sheerness. When Gregory sent Augustine to the conversion of England, the politic pope gave certain directions for the missionary's guidance. One referred to the delicate question of how the pagan customs which already existed among the Anglo-Saxons should be dealt with. Were they to be entirely abrogated, or were they to be tolerated as far as was not absolutely incompatible with the religion of the Gospel? Gregory said that he had thought much on this important subject, and finally had come to the conclusion that the heathen temples were not to be destroyed, but turned into Christian churches; that the oxen, which used to be killed in sacrifice, should still be killed with rejoicing, but their bodies given to the poor; and that the refreshment booths round the heathen temples should be allowed to remain as places of jollity and amusement for the people on Christian festivals. 'For,' he says, 'it is impossible to cut away abruptly from hard and rough minds all their old habits and customs. He who wishes to roach the highest place must rise by steps, and not by jumps.' And it would be inexcusable not to mention in The Book of Days, that it is through this judicious policy of Gregory that we still term the days of the week by their ancient Saxon appellations, derived in every instance from heathen deities. Christianity succeeded to Paganism, Norman followed Saxon, Rome has had to give way to Canterbury; yet the names of Odin, Thor, Tuisco, Saeter, and Friga are indelibly impressed upon our calendar. Colonists in distant climes delight to give the familiar names of places in their loved native land to newly - established settlements in the wilderness. Something of this very natural feeling may be seen in Augustine. The first heathen temple he consecrated for Christian worship in England he dedicated to St. Pancras. According to the legend, Pancras was a noble Roman youth, who, being martyred under Dioclesian at the early age of fourteen years, was subsequently regarded as the patron saint of children. There was a certain fitness, then, in dedicating the first church to him, in a country that owed its conversion to three children. But there was another and closer link connecting the first church founded in England by Augustine with St. Pancras. The much-loved monastery of St. Andrew, on the Coelian Mount, which Gregory had founded, and of which Augustine was prior, had been erected on the very estate that had anciently belonged to the family of Pancras. Nor was the monastery without its own more particular memorial. When Augustine founded a cathedral on the banks of the Medway, he dedicated it to St. Andrew, to perpetuate in barbarian Britain the old name so dear in civilized Italy; and subsequently St Paul's in London, and St Peter's in Westminster, represented on the banks of the Thames the great churches erected over the tombs of the two apostles of Rome beside the banks of the yellow Tiber. Little is known of Augustine's subsequent career in England; he is said to have visited the Welsh, and journeyed into Yorkshire. He died on the 26th of May, but the year is uncertain. FACSIMILES OF INEDITED AUTOGRAPHS CHARLES DUKE OF ORLEANSThe following is the signature of a remarkable and ill-fated man-the poet Duke of Orleans, father of Louis XII of France. He was the son of the elegant, gentlemanly, and most unprincipled Duke Louis, murdered in the streets of Paris in 1407. His mother, Valentina of Milan, 'that gracious rose of Milan's thorny stem,' died of a broken heart for the loss of her much-loved and unloving lord. Charles, the eldest of their four children, was born May 26, 1391. He was married in 1409, to his cousin, Princess Isabelle, the little widow of Richard II of England. She died in the following year, leaving one daughter. Charles exerted himself earnestly to procure the banishment of the Duke of Burgundy, suspected of inciting the murder of his father; but he was after some time most reluctantly persuaded to make peace with him. In 1415 he was taken prisoner at Agincourt, and confined in various English castles for the long term of twenty-five years. During his captivity he cultivated his poetical talent. In 1440 he was ransomed, and returned to France. His second wife, Bonne of Armagnac, having died without issue, Charles married, thirdly, Marie of Cleve, a lady with a fair face and fickle heart, by whom he had three children, Louis XII, and two daughters. He died on the 4th of June, 1465. One of his poems has been translated by Longfellow, and the English version of another, an elegy on his first wife, will be found in her memoir, in the Lives of the Queens of England. PEPYS AND HIS DIARYThe publication of the Diary of Samuel Pepys, in 1825, has given us an interest in the man which no consideration of his place in society, his services to the state, or any other of his acts, could ever have excited. It is little to us that Pepys was clerk to the Admiralty through a great part of the reign of Charles II, sat in several parliaments, and died in honour and wealth at a good age. What we appreciate him for is, that he left us a chronicle of his daily life, written in a strain of such frank unreserve as to appear like thinking aloud; and which preserves for us a vast number of traits of the era of the Restoration which in no other way could we have obtained. Mr. Pepys's Diary was written in short-hand, and though it was left amongst his other papers at his death, it may be doubted if he ever entertained the least expectation that it would be perused by a single human being besides himself. Commencing in 1659, and closing in 1669, it comprises the important public affairs connected with the Restoration, the first Dutch war, the plague and fire of London. It exhibits the author as a zealous and faithful officer, a moderate loyalist, a churchman of Presbyterian leanings-on the whole, a respectably conducted man; yet also a great gossip, a gadder after amusements, fond of a pretty female face besides that of his wife, vain and showy in his clothing, and greatly studious of appearances before the world. The charm of his Diary, however, lies mainly in its deliberate registration of so many of those little thoughts and reflections on matters of self which pass through every one's mind at nearly all times and seasons, but which hardly any one would think proper to acknowledge, much less to put into a historical form. The diarist's official duties necessarily brought him into contact with the court and the principal persons entrusted with the administration of affairs. Day by day he commits to paper his most secret thoughts on the condition of the state, on the management of affairs, on the silliness of' the king, the incompetency of the king's advisers, and the shamelessness of the king's mistresses. He tells us of a child 'being dropped at a ball at court, and that the king had it in his closet a week after, and did dissect it;' of a dinner given to the king by the Dutch ambassador, where, 'among the rest of the king's company there was that worthy fellow my Lord of Rochester, and Tom Killigrew, whose mirth and raillery offended the former so much that he did give Tom Killigrew a box on the ear in the king's presence;' and of a score more such scandalous events. He also gives us an insight into church matters at the time of the Restoration, and into the difficulties attending a reimposition of Episcopacy. Under date 4th November 1660, for instance, he observes: In the morn to our own church, where Mr Mills did begin to nibble at the Common Prayer, by saying, ' Glory be to the Father, &c.,' but the people had been so little used to it, that they could not tell what to answer. Pepys was an admirer and a good judge of painting, music, and architecture, and frequent allusions to these arts and their professors occur throughout the work; with respect to theatrical affairs he is very explicit. We are furnished with the names of the plays he witnessed, the names of their authors, the manner in which they were acted, and the favour with. which. they were received. His opinion of some well-known plays does not coincide with the judgment of more modern critics. For instance, of Midsummer Night's Dream he says: It is the most insipid, ridiculous play that ever I saw in my life;' and, again, of another of Shakspeare's he thus writes: ' To Deptford by water, reading Othello, Moor of Venice, which I ever heretofore esteemed a mighty good play; but having so lately react the Adventures of Five Houres, it seems a mean thing. His notices of literary works are frequently interesting; of Butler's Hudibras he thought little: It is so silly an abuse of the Presbyter Knight going to the warrs, that I am ashamed of it;' of Hobbes's Leviathan, he tells us that 30s. was the price of it, although it was heretofore sold for 8s., 'it being a book the bishops will not let be printed again. From 1684, Pepys occupied a handsome mansion at the bottom of Buckingham Street, Strand, the last on the west side, looking upon the Thames. Here, while president of the Royal Society, in 1684, he used to entertain the members. Another handsome house on the opposite side of the street, where Peter, the Czar of Russia, afterwards lived for some time, combines with Pepys's house, and the water-work tower of the York Buildings Company, to make this a rather striking piece of city scenery; and a picture of it, as it was early in the last century, is presented on next page. Pepys's house no longer exists.  Pepys, as has been remarked, was a church-man inclined to favour the Presbyterians; he was no zealot, but he never failed to have prayers daily in his house, and he rarely missed a Sunday at church. We learn from his Diary how an average Christian comported himself with respect to religion in that giddy time. Usually, before setting out for church, Pepys paid a due regard to the decoration of his person. 'The barber having done with me,' he says, 'I went to church.' We may presume that the operation was tedious. In November 1663, he began to wear a peruke, which was then a new fashion, and he seems to have been nervous about appearing in it at public worship. 'To church, where I found that my coming in a periwig did not prove so strange as I was afraid it would, for I thought that all the church would presently cast their eyes upon me, but I found no such thing.' A day or two before, he had been equally anxious on presenting himself in this guise before his patron and principal, the Earl of Sandwich. The earl 'wondered to see me in my perukuque, and I am glad it is over.' Pepys had a church to which he considered himself as attached; but he often-indeed, for the most part-went to others. One day, after attending his own church in the forenoon, and dining, he tells us, 'I went and ranged and ranged about to many churches, among the rest to the Temple, where I heard Dr. Wilkins a little.' It was something like a man of fashion looking in at a succession of parties in an evening of the London season. Very generally, Pepys makes no attempt to conceal how far secular feelings intruded both on his motives for going to church, and his thoughts while there. On the 11th August 1601, ' To our own church in the forenoon, and in the afternoon to Clerkenwell Church, only to see the two fair Botelers.' He got into a pew from which 'I had my full view of them both; but I am out of conceit now with them.' His general conduct at church was not good. In the first place, he allows his eyes to wander. He takes note of a variety of things: By coach to Greenwich Church, where a good sermon, a fine church, and a great company of handsome women.' On another occasion, attending a strange church, we are told, 'There was also my pretty black girl. Then, if anything ludicrous occurs, he has not a proper command of his countenance: 'Before sermon, I laughed at the reader, who, in his prayer, desired of God that he would imprint his Word on the thumbs of our right hands and on the right great toes of our right feet.' He even talks in church somewhat shamelessly, without excuse, or attempt at making excuse: 'In the pew both Sir Williams and I had much talk; about the death of Sir Robert.' Again, there was one more sad trick he had-he occasionally went to sleep: After dinner, to church again, my wife and I, where we had a dull sermon of a stranger, which made me sleep. Here he satisfies his conscience with excuses. But sometimes he is without excuse, and then is sorry: Sermon again, at which I slept; God forgive me! At church he has a habit of criticizing alike service and parson; and undeniably strange specimens of both seem to have come under his notice. First, the prayers. He goes to White Hall Chapel, 'with my lord,' but 'the ceremonies,' he says 'did not please me, they do so overdo them.' la fact, the singing takes his fancy much more. He is not without some skill himself: To the Abbey, and there meeting with Mr. Hooper, he took me in among the quire, and there I sang with them their service. It was very well for him he had this taste; for on one occasion, he tells us, a psalm was set which lasted an hour, while some collection or other was being made. He criticizes the congregation also, instead of bestowing his whole attention on what is going on. He observes, 'The three sisters of the Thornburys, very fine, and the most zealous people that ever I saw in my life, even to admiration, if it were true zeal.' He has his personal observations to make of the parson, with little show of reverence sometimes: 'Went to the red-faced parson's church.' There, however, 'I heard a good sermon of him, better than I looked for.' The sermon itself never escapes from his criticism. It is 'an excellent sermon,' or 'a dull sermon,' or 'a very good sermon,' or 'a lazy, poor sermon,' or 'a good, honest, and painful sermon.' He evidently expects the parson to take pains and be judicious: on one occasion ' an Oxford man gave us a most impertinent sermon,' and on another, 'a stranger preached like a fool.' But he does not seem to have minded these gentle-men availing themselves of the services of each other, or repeating their own discourses; he seems to have been quite used to it: I heard a good sermon of Dr Bucks, one I never heard before. He goes home to dinner; and, although he makes a point of remembering the text, he can seldom retain the exact words. It is generally after this fashion he has to enter it in the Diary: 'Heard a good sermon upon 'teach us the right way,' or something like it.' But, as a proof that he listened, he often favours us with a little abstract of how the subject was treated. Pepys's Sunday dinner is generally a good one -he is particular about it: 'My wife and I alone to a leg of mutton, the sauce of which being made sweet, I was angry at it, and ate none:' not that he went without dinner,-he 'dined on the marrow-bone, that we had beside.' Fasting did not suit him. He began, one first day of Lent, and says, 'I do intend to try whether I can keep it or no;' but presently we read, 'Notwithstanding my resolution, yet, for want of other victuals, I did eat flesh this Lent.' Now, how long would the reader fancy from that passage that he stood it?-alas! the register is made on the second day only! Then, after dinner, what does Mr. Pepys do? To put it simply, he enjoys himself. Often, indeed, he goes out to dinner (his wife going also), or has guests (with their wives) at his own house; but always, by some means or other, he contrives to get through a large amount of drinking before evening. 'At dinner and supper I drank, I know not how, of my own accord, so much wine, that I was even almost foxed, and my head aired all night.' Yet let us, in fairness, quote the rest: 'So home, and to bed, without prayers, which I never did yet, since I came to the house, of a Sunday night: I being now so out of order, that I durst not read prayers, for fear of being perceived by my servants in what case I was.' But this is not Mr. Pepys's only Sabbath amusement. He is musical: 'Mr. Childe and I spent some time at the lute.' Or he takes a very sober walk, to which the strictest will not object. In the evening (July), my father and I walked round past home, and viewed all the fields, which was pleasant.' Sometimes he treats himself to a more doubtful indulgence: 'Mr. Edward and I into Greye's Inn walks, and saw many beauties.' Nor was this an exceptional instance, or at a friend's instigation: 'I to Greye's Inn walk all alone, and with great pleasure, seeing the fine ladies walk there.' On some part of the day, unless he was in very bad condition,-as, for instance, that night when there were no prayers,-Mr. Pepys cast up his accounts. We read, 'Casting up my accounts, I do find myself to be worth ₤40 more, which I did not think.' Or, 'Stayed at home the whole afternoon, looking over my accounts.' And some-times he so far hurts his conscience by this proceeding as to be fain to make excuses and apologies: 'All the morning at home, making up my accounts (God forgive me!) to give up to my lord this afternoon.' SHUTE BARRINGTONThe venerable Shute Barrington, Bishop of Durham, died on the 25th of March 1826, at the great age of ninety-two, having exercised episcopal functions for fifty-seven years. It was remarkable that there should have been living to so late a period one whose father had been the friend of Locke, and the confidential agent of Lord Somers in bringing about the union between Scotland and England. While the revenues of his see were large, so also were his charities; one gentleman stated that fully a hundred thousand pounds of the bishop's money had come through his hands alone for the relief of cases of distress and woe. A military friend of Mrs. Barrington, being in want of an income, applied to the bishop, with a view to becoming a clergyman, thinking that his lordship might be enabled to provide for him. The worthy prelate asked how much income he required; to which the gentleman replied, that 'five hundred a year would make him a happy man.' 'You shall have it,' said the bishop; but not out of the patrimony of the church. I will not deprive a worthy and regular divine to provide for a necessitous relation. You shall have the sum you mention yearly out of my own pocket.' A curious circumstance connected with money occurred at the bishop's death. This event happening after 12 o'clock of the morning of the 25th, being quarter-day, gave his representatives the emoluments of a half-year, which would not have fallen to them had the event occurred before that hour. DUEL BETWEEN THE DUKE OF YORK AND COLONEL LENOXThe political excitement caused by the mental alienation of George the Third, and the desire of the Prince of Wales, aided by the Whig party, to be appointed Regent, was increased rather than allayed by the unexpected recovery of the king, early in 1789, and the consequent public rejoicings thereon. At that time the Duke of York was colonel of the Coldstream Guards, and Charles Lenox, nephew and heir to the Duke of Richmond, was lieutenant-colonel of the same regiment. Colonel Lenox being of Tory predilections, and having proposed the health of Mr. Pitt at a dinner-party, the Duke of York, who agreed with his brother in politics, determined to express his resentment against his lieutenant, which he did in the following manner: At a masquerade given by the Duchess of Ancaster, a gentleman was walking with the Duchess of Gordon, whom the duke, suspecting him to be Colonel Lenox, went up to and addressed, saying that Colonel Lenox had heard words spoken to him at D'Aubigny's club to which no gentleman ought to have submitted. The person thus addressed was not Colonel Lenox, as the duke supposed, but Lord Paget, who informed the former of the circumstance, adding that, from the voice and manner, he was certain the speaker was no other than the Duke of York. At a field day which happened soon after, the duke was present at the parade of his regiment, when Colonel Lenox took the opportunity of publicly asking him what were the words he (Lenox) had submitted to hear, and by whom were they spoken. The duke replied by ordering the colonel to his post. After parade, the conversation was renewed in the orderly room. The duke declined to give his authority for the alleged words at D'Aubigny's, but expressed his readiness to answer for what he had said, observing that he wished to derive no protection from his rank; when not on duty he wore a brown coat, and hoped that Colonel Lenox would consider him merely as an officer of the regiment. To which the colonel replied that he could not consider his royal highness as any other than the son of his king. Colonel Lenox then wrote a circular to every member of D'Aubigny's club, requesting to know whether such words had been used to him, begging an answer within the space of seven days; and adding that no reply would be considered equivalent to a declaration that no such words could be recollected. The seven days having expired, and no member of the club recollecting to have heard such words, Colonel Lenox felt justified in concluding that they had never been spoken; so he formally called upon the duke, through the Earl of Winchelsea, either to give up the name of his false informant, or afford the satisfaction usual among gentlemen. Accordingly, the duke, attended by Lord Rawdon, and Colonel Lenox, accompanied by the Earl of Winchelsea, met at Wimbledon Common (May 26th 1789). The ground was measured at twelve paces; and both parties were to fire at a signal agreed upon. The signal being given, Lenox fired, and the ball grazed his royal highness's side curl: the Duke of York did not fire. Lord Rawdon then interfered, and said he thought enough had been done. Lenox observed that his royal highness had not fired. Lord Rawdon said it was not the duke's intention to fire; his royal highness had come out, upon Colonel Lenox's desire, to give him satisfaction, and had no animosity against him. Lenox pressed that the duke should fire, which was declined, with a repetition of the reason. Lord Winchelsea then went up to the Duke of York, and expressed his hope that his royal highness could have no objection to say he considered. Colonel Lenox a man of honour and courage. His royal highness replied, that he should say nothing: he had come out to give Colonel Lenox satisfaction, and did not mean to fire at him; if Colonel Lenox was not satisfied, he might fire again. Lenox said he could not possibly fire again at the duke, as his royal highness did not mean to fire at him. On this, both parties left the ground. Three days afterwards, a meeting of the officers of the Coldstream Guards took place on the requisition of Colonel Lenox, to deliberate on a question which he submitted.; namely, whether he had behaved in the late dispute as became an officer and a gentleman. After considerable discussion and an adjournment, the officers came to the following resolution: 'It is the opinion of the Coldstream regiment, that subsequent to the 15th of May, the day of the meeting at the orderly room, Lieut. Col. Lenox has behaved with courage, but, from the peculiar difficulty of his case, not with judgment.' The 4th of June being the king's birthday, a grand ball was held at St. James's Palace, which came to an abrupt conclusion, as thus described in a magazine of the period: 'There was but one dance, occasioned, it is said, by the following circumstance. Colonel Lenox, who had not danced a minuet, stood up with Lady Catherine Barnard. The Prince of Wales did not see this until he and his partner, the princess royal, came to Colonel Lenox's place in the dance, when, struck with the incongruity, he took the princess's hand, just as she was about to be turned by Colonel Lenox, and led her to the bottom of the dance. The Duke of York and the Princess Augusta came next, and they turned the colonel without the least particularity or exception. The Duke of Clarence, with the Princess Elizabeth, came next, and his highness followed the example of the Prince of Wales. The dance proceeded, however, and Lenox and his partner danced down. When they came to the prince and princess, his royal highness took his sister, and led her to her chair by the queen. Her majesty, addressing herself to the Prince of Wales, said-'You seem heated, sir, and tired!' 'I am heated and tired, madam,' said the prince, 'not with the dance, but with dancing in such company.' 'Then, sir,' said the queen, 'it will be better for me to withdraw, and put an end to the ball,' 'It certainly will be so,' replied the prince, 'for I never will countenance insults given to my family, however they may be treated by others.' Accordingly, at the end of the dance, her majesty and the princesses withdrew, and the ball concluded. The Prince of Wales explained to Lady Catherine Barnard the reason of his conduct, and assured her that it gave him much pain that he had been under the necessity of acting in a manner that might subject a lady to a moment's embarrassment.' A person named Swift wrote a pamphlet on the affair, taking the duke's side of the question. This occasioned another duel, in which Swift was shot in the body by Colonel Lenox. The wound, however, was not mortal, for there is another pamphlet extant, written by Swift on his own duel. Colonel Lenox immediately after exchanged into the thirty-fifth regiment, then quartered at Edinburgh. On his joining this regiment, the officers gave a grand entertainment, the venerable castle of the Scottish metropolis was brilliantly illuminated, and twenty guineas were given to the men for a merry-making. Political feeling, the paltry conduct of the duke, the bold and straightforward bearing of the colonel, and probably a lurking feeling of Jacobitism-Lenox being a left-handed descendant of the Stuart race-made him the most popular man in Edinburgh at the time. The writer has frequently heard an old lady describe the clapping of hands, and other popular emanations of applause, with which Colonel Lenox was received in the streets of Edinburgh. MANDRINIt is a curious consideration regarding France, that she had a personage equivalent to the Robin Hood of England and the Rob Roy of the Scottish Highlands, after the middle of the eighteenth century. We must look mainly to bad government and absurd fiscal arrangements for an explanation of this fact. Louis Mandrin had served in the war of 1740, in one of the light corps which made it their business to undertake unusual dangers for the surprise of the enemy. The peace of 1748 left him idle and without resource; he had no other mode of supporting life than to be continually risking it. In these circumstances, he bethought him of assembling a corps of men like himself, and putting himself at their head; and began in the interior of France an open war against the farmers and receivers of the royal revenues. He made himself master of Autun, and of some other towns, and pillaged the public treasuries to pay his troops, whom he also employed in forcing the people to purchase contraband merchandise. He beat off many detachments of troops sent against him. The court, which was at Marly, began to be afraid. The royal troops showed a strong reluctance to operate against Mandrin, considering it derogatory to engage in such a war; and the people began to regard him as their protector against the oppressions of the revenue officers. At length, a regiment did attack and destroy Mandrin's corps. He escaped into Switzerland, whence for a time he continued to infest the borders of Dauphiny. By the baseness of a mistress, he was at length taken and conducted into France; his captors unscrupulously breaking the laws of Switzerland to effect their object, as Napoleon afterwards broke those of Baden for the seizure of the Duc d'Enghien. Conducted to Valence, he was there tried, and on his own confession condemned to the wheel. He was executed on the 26th of May 1755. CORPUS CHRISTI DAY (1864)This is a festival of the Roman Catholic Church held on the Thursday after Whit Sunday, being designed in honour of the doctrine of transubstantiation. It is a day of great show and rejoicing; was so in England before the Reformation, as it still is in all Catholic countries. The main feature of the festival is a procession, in which the pyx containing the consecrated bread is carried, both within the church and throughout the adjacent streets, by one who has a canopy held over him. Sundry figures follow, representing favorite saints in a characteristic manner-Ursula with her many maidens, St. George killing the dragon, Christopher wading the river with the infant Saviour upon his shoulders, Sebastian stuck full of arrows, Catherine with her wheel; these again succeeded by priests bearing each a piece of the sacred plate of the church. The streets are decorated with boughs, the pavement strewed with flowers, and a venerative multitude accompany the procession. As the pyx approaches, every one falls prostrate before it. The excitement is usually immense. After the procession there used to be mystery or miracle plays, a part of the ceremonial which in some districts of this island long survived the Reformation, the Protestant clergy vainly endeavoring to extinguish what was not merely religion, but amusement. |