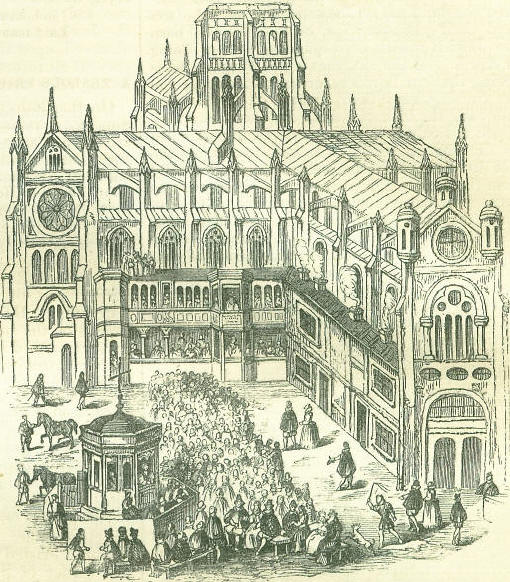

26th MarchBorn: Conrad Gesner, eminent scholar and naturalist, 1516, Zurich; William Wollaston, author of The Religion of Nature Delineated, 1659, Coton Clanford, Staffordshire; George Joseph Bell, writer on law and jurisprudence, 1770, Fountainbridge, Edinburgh. Died: Bishop Brian Duppa, 1662, Richmond; William Courten, traveller and virtuoso, 1702, Kensington; Sir John Vanbrugh, architect and dramatist, 1726, Whitehall; C. P. Duclos, French romance writer, 1772, Paris; John Mitchell Kemble, Anglo-Saxon scholar and historian, 1857; John Seaward, engineer, 1858. Feast Day: St. Braulio, Bishop of Saragossa, 646. St. Ludger, Bishop of Munster, Apostle of Saxony, 809. HOLY SATURDAY IN ROMEOn the reading of a particular passage in the service of the Sistine Chapel, which takes place about half-past eleven o'clock, the bells of St. Peter's are rung, the guns of St. Angelo are fired, and all the bells in the city immediately break forth, as if rejoicing in their renewed liberty of ringing. This day, at St. Peter's, the only ceremony that need be noticed is the blessing of the fire and the paschal candle. For this purpose, new fire, as it is called, is employed. At the beginning of mass, a light, from which the candles and the charcoal for the incense is enkindled, is struck from a flint in the sacristy, where the chief sacristan privately blesses the water, the fire, and the five grains of incense which are to be fixed in the paschal candle. Formerly, all the fires in Rome were lighted anew from this holy fire, but this is no longer the case. After the service, the cardinal vicar proceeds to the baptistry of St. Peter's; there having blessed and exorcised the water for baptism, and dipped into the paschal candle, concludes by sprinkling some of the water on the people. Catechumens are afterwards baptized, and deacons and priests are ordained, and the tonsure is given. DEATH OF SIR JOHN VANBRUGILIn a diminutive house, which he had built for himself at Whitehall with the ruins of the old palace, died Sir John Vanbrugh, 'a man of wit and man of honour,' leaving a widow many years younger than himself, but no children, his only son having been killed at the battle of Tournay. Vanbrugh was of Dutch descent, and the son of a sugar-baker at Chester, where he was born in 1666. We have no account of his being educated for the profession of an architect: he is believed to have been sent to France at the age of nineteen, and there studied architecture; and being detected in making drawings of some fortifications, he was imprisoned in the Bastile. He became a dramatic writer and a herald; in the first he excelled, but his wit and vivacity were of a loose kind: hence Pope says, 'Van wants grace,' &c. Still he borrowed little, and when he translated, he enriched his author. He built, as a speculation of his own, a theatre in the Haymarket, which afterwards became the original Opera-house, on the site of the present building. In this scheme he had Congreve for his dramatic coadjutor, and Betterton for manager, by whom the house was opened in 1706; and here Vanbrugh's admirable comedy of The Confederacy was first brought out. Many years before this, Vanbrugh had acquired some reputation for architectural skill; for in 1695 he was appointed one of the commissioners for completing the palace at Greenwich, when it was about to be converted into an hospital. In 1702, he produced the palace of Castle Howard for his patron, the Earl of Carlisle, who being then Earl Marshal of England, bestowed upon Vaubrugh the not unprofitable appointment of Clarencieux, King-at-Arms. His work of Castle Howard recommended him as architect to many noble and wealthy employers, and to the appointment to build a palace to be named after the victory at Blenheim. This brought the architect vexation as well as fame; for Duchess Sarah, 'that wicked woman of Marlborough,' as Vanbrugh calls her, discharged him from his post of architect, and refused to pay what was due to him as salary. Sir Joshua Reynolds declared Vaubrugh to have been defrauded of the due reward of his merit, by the wits of the time, who knew not the rules of architecture. 'Vanbrugh's fate was that of the great Perault: both were objects of the petulant sarcasms of factious men of letters; and both have left some of the fairest monuments which, to this day, decorate their several countries,-the facades of the Louvre, Blenheim, and Castle Howard.' Reynolds was among the first to express his approbation of Vaubrugh's style, and to bear his testimony as an artist to the picturesque magnificence of Blenheim. The wits were very severe on Vanbrugh. Swift, speaking of his diminutive house at Whitehall, and the stupendous pile at Blenheim, says of the former: At length they in the corner spy A thing resembling a goose pye. Of the palace at Blenheim: That, if his Grace were no more skill'd in The art of battering walls than building, We might expect to see next year A mousetrap man chief engineer. This ridicule pursued Vanbrugh to his epitaph, for after his remains had been deposited in Wren's beautiful church of St. Stephen's, Walbrook, Dr. Evans, alluding to Vanbrugh's massive style, wrote: Lie heavy on him, earth, for he Laid many a heavy load on thee. A ZEALOUS FRIEND OF St. PAUL'S CATHEDRALOn the 26th of March 1620, being Midlent Sunday, a remarkable assemblage took place around St. Paul's Cross, London. St Paul's Cathedral had lain in a dilapidated state for above fifty years, having never quite recovered the effects of a fire which took place in 1561. At length, about 1612, an odd busy being, called Henry Farley-one of those people who are always going about poking the rear of the public to get them to do something-took up the piteous call of the fine old church, resolved never to rest till he had procured its thorough restoration. He issued a variety of printed appeals on the subject, beset state officers to get bills introduced into Parliament, and in 1616 had three pictures painted on panel; one representing a procession of grand personages, another the said personages seated at a sermon at St. Paul's Cross, both being incidents which he wished to see take place as a commencement to the desired work. The cut on next page is a reduction of the latter extraordinary picture, which Farley lived to see realized on the day cited at the head of this little article.  The picture [above] represents that curious antique structure, the Preaching Cross, which for centuries existed in the vacant space at the north-east corner of St. Paul's churchyard, till it was demolished by a Puritan lord mayor at the beginning of the Civil War. A gallery placed against the choir of the church contains, in several compartments, the King, Queen, and Prince of Wales, the Lord Mayor, &c., while a goodly corps of citizens sit in the area in front of the Cross. Most probably, when the King came in state with his family and court, to hear the sermon which was actually preached here on Midlent Sunday, 1620, the scene was very nearly what is here presented. One of Farley's last efforts for the promotion of the good work he had taken in hand, was the publication of a tract in twenty-one pages, in the year 1621. After some other matters, it gives a petition to the King, written in the name of the church, which introduces Farley to notice as' the poore man who hath been my voluntary servant these eight years, by books, petitions, and other devises, even to his owne dilapidations. It also contains a petition which Farley had prepared to be given to the King two days before the Midlent sermon, but which the Master of Bequests had taken away before the King could read it: as many had been so taken before, to the great hindrance and grief of the poore author. In this address, the church thus speaks: Whereas, to the exceeding great joy of all my deare friends, there is certaine intelligence that your Highnesse will visit me on Sunday next, and the rather I believe it, for that I have had more sweeping, brushing, and cleansing than I have had in forty years before. Then the author adds a recital of the various efforts he had to attract the royal attention to St. Paul's. He had assailed him with 'carols' on various occasions. He had published a' Dream,' prefiguring what he wished to see effected. Towards the last, he tells the church: I grew much dismayed .. . Many rubs I ran through; many scoffes and scornes I did undergo; forsaken by butterflie friends; laughed at and derided by your enemies; pursued after by wolves of Wood Street and foxes of the Poultrey, sometimes at the point of death and despaire. Instead of serving my Prince (which I humbly desired, though but as a doorkeeper in you), I was presst for the service of King Lud [put into Ludgate prison], when all the comfort I had was that I could see you, salute you, and condole with your miseries [the prison being in a tower crossing the street of Ludgate Hill; consequently commanding a view of the west front of the church]. My poore clothes and ragges I could not compare to anything better than to your west end, and my service to you nothing lesse than bond-age. In the midst of his troubles, when thinking of quitting all and going to Virginia, he heard of the King's intended visit, and was comforted. The tract ends with St. Paul's giving Mr. Farley a promise that, for his long and faithful services, he should have a final resting-place within her walls. |