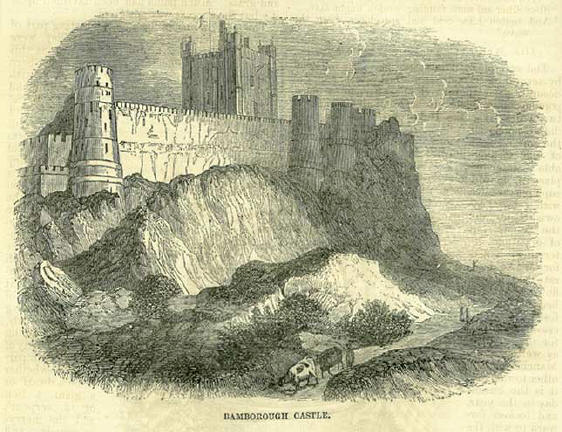

24th JuneBorn: Theodore Beza, reforming divine, 1519, Vezelai, in Burgundy; John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough, 1650, Ache, Devonshire; Dr. Alexander Adam, eminent classical teacher, 1741, Rafford, near Forres; Deodatus de Dolomieu, mineralogist, 1750, Grenoble; Josephine, Empress of the French, 1763, Martinico; General Hoche, 1768, Montreuil; Rear-Admiral Sir John Ross, Arctic navigator, 1777; Alexander Dumas, French novelist, 1803. Died: Vespasian, Emperor of Rome, 79, Cutilia; Nicolas Claude Pierese, 1637, Aix, Provence; John Hampden, illustrious patriot, 1643, Thame; Bishop Isaac Barrow, 1680, St. Asaph; Nicolas Harrison, historian, 1720; Dr. Thomas Amory, English Presbyterian divine, miscellaneous writer, 1774. Feast Day: Nativity of St. John the Baptist. The Martyrs of Rome under Nero, 1st century. St. Bartholomew of Dunelm. MIDSUMMER DAY - THE NATIVITY OF JOHN THE BAPTISTConsidering the part borne by the Baptist in the transactions on which Christianity is founded, it is not wonderful that the day set apart for the observance of his nativity should be, in all ages and most parts of Europe, one of the most popular of religious festivals. It enjoys the greater distinction that it is considered as Midsummer Day, and therefore has inherited a number of observances from heathen times. These are now curiously mixed with those springing from Christian feelings, insomuch that it is not easy to distinguish them from the other. It is only clear, from their superstitious character, that they have been originally pagan. To use the quaint phrase of an old translator of Scaliger, they 'form the footesteps of auncient gentility;' that is, gentilism or heathenism. The observances connected with the Nativity of St. John commenced on the previous evening, called, as usual, the eve or vigil of the festival, or Midsummer eve. On that evening the people were accustomed to go into the woods and break down branches of trees, which they brought to their homes, and planted over their doors, amidst great demonstrations of joy, to make good the Scripture prophecy respecting the Baptist, that many should rejoice in his birth. This custom was universal in England till the recent change in manners. In Oxford there was a specialty in the observance, of a curious nature. Within the first court of Magdalen College, from a stone pulpit at one corner, a sermon was always preached on St. John's Day; at the same time the court was embowered with green boughs, 'that the preaching might resemble that of the Baptist in the wilderness.' Towards night, materials for a fire were collected in a public place and kindled. To this the name of bonfire was given, a term of which the most rational explanation seems to be, that it was composed of contributions collected as boons, or gifts of social and charitable feeling. Around this fire the people danced with almost frantic mirth, the men and boys occasionally jumping through it, not to show their agility, but as a compliance with ancient custom. There can be no doubt that this leaping through the fire is one of the most ancient of all known superstitions, and is identical with that followed by Manasseh. We learn that, till a late period, the practice was followed in Ireland on St. John's Eve. It was customary in towns to keep a watch walking about during the Midsummer Night, although no such practice might prevail at the place from motives of precaution. This was done at Nottingham till the reign of Charles I. Every citizen either went himself, or sent a substitute; and an oath for the preservation of peace was duly administered to the company at their first 'meeting at sunset. They paraded the town in parties during the night, every person wearing a garland of flowers upon his head, additionally embellished in some instances with ribbons and jewels. In London, during the middle ages, this watch, consisting of not less than two thousand men, paraded both on this night and on the eves of St. Paul's and St. Peter's days. The watchmen were provided with cressets, or torches, carried in barred pots on the tops of long poles, which, added to the bonfires on the streets, must have given the town a striking appearance in an age when there was no regular street-lighting. The great came to give their countenance to this marching watch, and made it quite a pageant. A London poet, looking back from 1616, thus alludes to the scene: The goodly buildings that till then did hide Their rich array, open'd their windows wide, Where kings, great peers, and many a noble dame, Whose bright pearl-glittering robes did mock the flame Of the night's burning lights, did sit to see How every senator in his degree, Adorn'd with shining gold and purple weeds, And stately mounted on rich-trapped steeds, Their guard attending, through the streets did ride, Before their foot-bands, graced with glittering pride Of rich-gilt arms, whose glory did present A sunshine to the eye, as if it meant, Among the cresset lights shot up on high, To chase dark night for over from the sky; While in the streets the sticklers to and fro, To keep decorum, still did come and go, Where tables set were plentifully spread, And at each door neighbour with neighbour fed. King Henry VIII, hearing of the marching watch, came privately, in 1510, to see it; and was so much pleased with what he saw, that he came with Queen Catherine and a noble train to attend openly that of St. Peter's Eve, a few nights after. But this king, in the latter part of his reign, thought proper to abolish the ancient custom, probably from a dread of so great a muster of armed citizens. Some of the superstitious notions connected with St. John's Eve are of a highly fanciful nature. The Irish believe that the souls of all people on this night leave their bodies, and wander to the place, by land or sea, where death shall finally separate them from the tenement of day. It is not improbable that this notion was originally universal, and was the cause of the widespread custom of watching or sitting up awake on St. John's night, for we may well believe that there would be a general wish to prevent the soul from going upon that somewhat dismal ramble. In England, and perhaps in other countries also, it was believed that, if any one sat up fasting all night in the church porch, he would see the spirits of those who were to die in the parish during the ensuing twelvemonths come and knock at the church door, in the order and succession in which they were to die. We can easily perceive a possible connexion between this dreary fancy and that of the soul's midnight ramble. The civic vigils just described were no doubt a result, though. a more remote one, of the same idea. There is a Low Dutch proverb used by those who have been kept awake all night by troubles of any kind: We have passed St. John Baptist's night.' In a book written in the seventeenth century for the instruction of a young nobleman, the author warns his pupil against certain 'fearful superstitions, as to watch upon St. John's evening, and the first Tuesday in the month of March, to conjure the moon, to lie upon your back, having your ears stopped with laurel leaves, and to fall asleep not thinking of God, and such like follies, all forged by the infernal Cyclops and Pluto's servants. A circumstance mentioned by Grose supports our conjecture-that to sleep on St. John's Eve was thought to ensure a wandering of the spirit, while watching was regarded as conferring the power of seeing the vagrant spirits of those who slept. Amongst a company who sat up in a church porch, one fell so deeply asleep that he could not be waked. His companions after-wards averred that, whilst he was in this state, they beheld his spirit go and knock at the church door. The same notion of a temporary liberation of the soul is perhaps at the bottom of a number of superstitious practices resembling those appropriate to Hallow-eve. It was supposed, for example, that if an unmarried woman, fasting, laid a cloth at midnight with bread and cheese, and sat down as if to eat, leaving the street-door open, the person whom she was to marry would come into the room and drink to her by bowing, after which, setting down the glass, with another bow he would retire. It was customary on this eve to gather certain plants which were supposed to have a supernatural character. The fern is one of those herbs which have their seed on the back of the leaf, so small as to escape the sight. It was concluded, according to the strange irrelative reasoning of former times, that to possess this seed, not easily visible, was a means of rendering one's self invisible. Young men would go out at midnight of St. John's Eve, and endeavour to catch. some in a plate, but without touching the plant-an attempt rather trying to patience, and which often failed. Our Elizabethan dramatists and poets, including Shakspeare and Jonson, have many allusions to the invisibility-conferring powers of fern seed. The people also gathered on this night the rose, St. John's wort, vervain, trefoil, and rue, all of which were thought to have magical properties. They set the orpine in clay upon pieces of slate or potsherd in their houses, calling it a Midsummer Man. As the stalk was found next morning to incline to the right or left, the anxious maiden knew whether her lover would prove true to her or not. Young women likewise sought for what they called pieces of coal, but in reality, certain hard, black, dead roots, often found under the living mugwort, designing to place these under their pillows, that they might dream of their lovers. Some of these foolish fancies are pleasantly strung together in the Connoisseur, a periodical paper of the middle of the last century. 'I and my two sisters tried the dumb cake together; you must know two must make it, two bake it, two break it, and the third put it under each of their pillows (but you must not speak a word all the time), and then you will dream of the man you are to have. This we did; and, to be sure, I did nothing all night but dream of Mr. Blossom. The same night, exactly at twelve o'clock, I sowed hemp-seed in our backyard, and said to myself-'Hemp-seed I sow, hemp-seed I hoe, and he that is my true love come after me and mow.' Will you believe me? I looked back and saw him as plain as eyes could see him. After that I took a clean shift and wetted it, and turned it wrong side out, and hung it to the fire upon the back of a chair; and very likely my sweetheart would have come and turned it right again (for I heard his step), but I was frightened, and could not help speaking, which broke the charm. I likewise stuck up two Mid-summer Men, one for myself and one for him. Now, if his had died away, we should never have come together; but I assure you his bowed and turned to mine. Our maid Betty tells me, if I go backwards, without speaking a word, into the garden upon Midsummer Eve, and gather a rose, and keep it in a clean sheet of paper, without looking at it till Christmas Day, it will be as fresh as in June; and if I then stick it in my bosom, he that is to be my husband will come and take it out.' So also, in a poem entitled the Cottage Girl, published in 1786: The moss rose that, at fall of dew, Ere eve its duskier curtain drew, Was freshly gather'd from its stem, She values as the ruby gem; And, guarded from the piercing air, With all an anxious lover's care, She bids it, for her shepherd's sake, Await the new-year's frolic wake, When, faded in its alter'd hue, She reads-the rustic is untrue! But if its leaves the crimson paint, Her sickening hopes no longer faint; The rose upon her bosom worn, She meets him at the peep of morn, And lo! her lips with kisses prest, He plucks it from her panting breast. We may suppose, from the following version of a German poem, entitled The St. John's Wort, that precisely the same notions prevail amongst the peasant youth of that country: The young maid stole through the cottage door, And blushed as she sought the plant of power: 'Thou silver glow-worm, oh, lend me thy light, I must gather the mystic St. John's wort tonight- The wonderful herb, whose leaf will decide If the coining year shall make me a bride.' And the glow-worm came With its silvery flame, And sparkled and shone Through the night of St. John. And soon has the young maid her love-knot tied. With noiseless tread, To her chamber she sped, Where the spectral moon her white beams shed: 'Bloom here, bloom here, thou plant of power, To deck the young bride in her bridal hour! But it droop'd its head, that plant of power, And died the mute death of the voiceless flower; And a wither'd wreath on the ground it lay, More meet for a burial than bridal day. And when a year was past away, All pale on her bier the young maid lay; And the glow-worm came With its silvery flame, And sparkled and shone Through the Eight of St. John, As they closed the cold grave o'er the maid's cold day. Some years ago there was exhibited before the Society of Antiquaries a ring which had been found in a ploughed field near Cawood in Yorkshire, and which appeared, from the style of its inscriptions, to be of the fifteenth century. It bore for a device two orpine plants joined by a true love knot, with this motto above, Alec fiancee velt, that is, My sweetheart wills, or is desirous. The stalks of the plants were bent towards each other, in token, no doubt, that the parties represented by them were to come together in marriage. The motto under the ring was Joye l'amour feu. So universal, in time as in place, are these popular notions. The observance of St. John's Day seems to have been, by a practical bull, confined mainly to the previous evening. On the day itself, we only find that the people kept their doors and beds embowered in the branches set up the night before, upon the understanding that these had a virtue in averting thunder, tempest, and all kinds of noxious physical agencies. The Eve of St. John is a great day among the mason-lodges of Scotland. What happens with them at Melrose may be considered as a fair example of the whole. 'Immediately after the election of office-bearers for the year ensuing, the brethren walk in procession three times round the Cross, and afterwards dine together, under the presidency of the newly-elected Grand Master. About six in the evening, the members again turn out and form into line two abreast, each bearing a lighted flambeau, and decorated with their peculiar emblems and insignia. Headed by the heraldic banners of the lodge, the pro-cession follows the same route, three times round the Cross, and then proceeds to the Abbey. On these occasions, the crowded streets present a scene of the most animated description. The joyous strains of a well-conducted band, the waving torches, and incessant showers of fire-works, make the scene a carnival. But at this time the venerable Abbey is the chief point of attraction and resort, and as the mystic torch-bearers thread their way through its mouldering aisles, and round its massive pillars, the outlines of its gorgeous ruins become singularly illuminated and brought into bold and striking relief. The whole extent of the Abbey is with 'measured step and slow ' gone three times round. But when near the finale, the whole masonic body gather to the chancel, and forming one grand semicircle around it, where the heart of King Robert Bruce lies deposited near the high altar, and the band strikes up the patriotic air, ' Scots wha ha'e wi' Wallace bled,' the effect produced is overpowering. Midst showers of rockets and the glare of blue lights the scene closes, the whole reminding one of some popular saturnalia held in a monkish town during the middle ages.'-Wade's Hist. Melrose, 1861, p. 146. FOUNDATION OF THE ORDER OF THE GARTERIt is concluded by the best modern authorities that the celebrated Order of the Garter, which European sovereigns are glad to accept from the British monarch, was instituted some time between the 24th of June and the 6th of August 1348. The founder, Edward III, was, as is well known, addicted to the exercises of chivalry, and was frequently holding jousts and tournaments, at some of which he himself did not disdain to wield a spear. Some years before this date, he had gone some way in forming an order of the Round Table, in commemoration of the legend of King Arthur, and, in January 1341, he had caused an actual round table of two hundred feet diameter to be constructed in Windsor Castle, where the knights were entertained at his expense, the effect being that he thus gathered around him a host of ardent spirits, highly suitable to assist in his contemplated wars against France. Before the date above mentioned, a turn had been given to the views of the king, leading him to adopt a totally different idea for the basis of the order. 'The popular account is, that, during a festival at court, a lady happened to drop her garter, which was taken up by King Edward, who, observing a significant smile among the bystanders, exclaimed, with some displeasure, 'Honi soit qui mal y pense' - 'Shame to him who thinks ill of it.' In the spirit of gallantry, which belonged no less to the age than to his own disposition, conformably with the custom of wearing a lady's favour, and perhaps to prevent any further impertinence, the king is said to have placed the garter round his own knee.'-Tighe and Davis's Annals of Windsor. It is commonly said that the fair owner of the garter was the Countess of Salisbury; but this is a point of as much doubt as delicacy, and there have not been wanting those who consider the whole story fabulous. Scepticism, however, rests mainly on the ridiculous character of the incident above described, a most fallacious basis, we must say in all humility, and rather indeed a support to the popular story, considering how outrageously foolish are many of the authenticated practices of chivalry. It is to be remarked that the tale is far from being modern. It is related by Polydore Virgil so early as the reign of Henry VII. Although the order is believed to have been not founded before June 24th, 1348, it is certain that the garter itself was become an object of some note at court in the autumn of the preceding year, when at a great tournament held in honour of the king's return from France, 'garters with the motto of the order embroidered there-on, and robes and other habiliments, as well as banners and couches, ornamented with the same ensign, were issued from the great wardrobe at the charge of the sovereign.'* The royal mind was evidently by this time deeply interested in the garter. A surcoat furnished to him in 1348, for a spear play or hastilude at Canterbury, was covered with garters. At the same time, the youthful Prince of Wales presented twenty-four garters to the knights of the society. RELIEF OF SHIPWRECKED MARINERS AT BAMBOROUGH CASTLEBy his will of this date, in 1720, Lord Crewe, Bishop of Durham, left Bamborough Castle, and extensive manors in its neighbourhood, for various charitable and other purposes, including the improvement of certain church livings. The annual proceeds amounted a few years ago to £8126,8s. 8d., being much more than was necessary for the purposes originally contemplated. The trustees have accordingly for many years devoted a part of the funds to the support of an establishment in the castle of Bamborough, directed to the benefit of distressed vessels and shipwrecked seamen.  This castle crowns the summit of a basalt rock, a hundred and fifty feet high, starting up from a sandy tract on a dangerous part of the coast of Northumberland. The buildings are most picturesque, and they derive a moral interest from the purpose to which they are devoted. 'The trustees have ready in the castle such implements as are required to give assistance to stranded vessels; a nine-pounder is placed at the bottom of the great tower, which gives signals to ships in distress, and, in case of wreck, announces the same to the custom-house officers and their servants, who hasten to prevent the wreck being plundered. A constant watch is kept at the top of the great tower, whence signals are also made to the fishermen of Holy Island, as soon as any vessel is discovered to be in distress, when the fishermen immediately put off to its assistance, and the signals are so regulated as to point out the particular direction in which the vessel lies; and this is partly indicated by flags by day, and rockets at night. Owing to the size and fury of the breakers, it is generally impossible for boats to put off from the main land in a severe storm, but such difficulty occurs but rarely in putting off from Holy Island. In addition to these arrangements for mariners in distress, men on horseback constantly patrol the coast, a distance of eight miles, from sunset to sunrise, every stormy night. Whenever a case of shipwreck occurs, it is their duty to forward intelligence to the castle without delay; and, as a further inducement to this, premiums are often given for the earliest notice of such distress. During the continuance of fogs, which are frequent and sudden, a gun is fired at short intervals. By these means many lives are saved, and an asylum is offered to ship-wrecked persons in the castle. The trustees also covenant with the tenants of the estate, that they shall furnish carts, horses, and men, in proportion to their respective farms, to protect and bring away whatever can be saved from the wrecks. There are likewise the necessary tackle and instruments kept for raising vessels which have sunk, and whatever goods may be saved are deposited in the castle. The bodies of those who are lost are decently interred at the expense of this charity-in fact, to sailors on that perilous coast, Bamborough Castle is what the convent of St. Bernard is to travellers in the Alps.' The Rev. Mr. Bowles thus addresses Bainborough Castle with reference to its charitable purpose: Ye holy towers, that shade the wave-worn steep, Long may ye rear your aged brows sublime, Though, hurrying silent by, relentless Time Assail you, and the winter whirlwinds sweep! For far from blazing Grandeur's crowded halls, Here Charity hath fix'd her chosen seat; Oft list'ning tearful when the wild winds beat With hollow bodings round your ancient walls! And Pity, at the dark and stormy hour Of midnight, when the moon is hid on high, Keeps her lone watch upon the topmost tower, And turns her car to each expiring cry! Blest if her aid some fainting wretch might save, And snatch him, cold and speechless, from the wave. THE WELL-FLOWERING AT BUXTONThe example of Tissington has been followed by several of the towns of Derbyshire, and the decoration of their wells has become a most popular amusement. It is (1862) about twenty-two years since the Duke of Devonshire, who did so much for the improvement of the fashionable watering-place of Buxton, supplied the town with water at his own expense, and the people, out of gratitude, determined hence-forward to decorate the taps with flowers; this has become such a festival from the crowds arriving for miles round, as well as from Manchester and other towns, that it is the busiest day in the year, and looked for-ward to with the utmost pleasure by young and old. Vehicles of all kinds, and sadly overloaded, pour in at an early hour; the streets are filled with admiring groups, and bands of music parade the town.  The crescent walks are planted with small firs, and the pinnacles of the bath-house have each a little flag-alternately pink, white, blue, and yellow -the effect of which is extremely good, connected as they are by festoons of laurel. But the grand centres of attraction are the two wells. On an occasion when we visited the place, that of St. Anne's was arched over; the whole groundwork covered with flowers stuck into plaster, and on a ground of buttercups were inscribed, in red daisies, the words 'Life, Love, Liberty, and Truth.' Ferns and rockwork were gracefully arranged at the foot, and amidst them a swan made of the white rocket, extremely well modelled; an oak branch supported two pretty white doves, and pillars wreathed with rhododendrons completed the design, which was on the whole very pretty. We can scarcely say so much for the well in the higher town, which was a most ambitious attempt to depict 'Samson slaying the lion,' in ferns, mosses, fir cones, blue bells, buttercups, peonies, and daisies-a structure twenty feet high, the foreground being occupied with miniature fountains, rockwork, and grass. Much pains had been lavished upon it; but the success was not great. The morris-dancers form an interesting part of the day's amusements. Formerly they were little girls dressed in white muslin; but as this was considered objectionable, they have been replaced by young men gaily decorated with ribbons, who come dancing down the hill, and when they reach the pole in the centre of the crescent fasten the long ribbons to it, and in mystic evolutions plait them into a variety of forms, as they execute what is called the Ribbon Dance. In the meantime the children are de-lighting themselves in the shows, of which there are abundance, the men at the entrance of each clashing their cymbals, and proclaiming the superiority of their own in particular-whether it be a dwarf or a giant, a lion or a serpent; and the merry-go-rounds and swing-boats find plenty of customers. Altogether, it must be allowed that there is a genial and kindly influence in the well-flowering which we should be sorry to see abolished in these days, when holidays, and the right use of them, is a question occupying so many minds. The tap-dressing at Wirksworth is too similar to those at Tissington and Buxton to require any further description. This curious little town, surrounded by hills, looks gay indeed every Whitsuntide, which is the season at which the wakes are held and the taps dressed; the mills around are emptied of their workers, and friends assemble from all the neighbourhood. This custom has been established about a hundred and seven years, in gratitude for the supply of water which was procured for the town when the present pipes were laid down. |