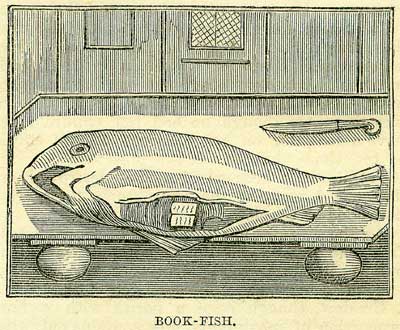

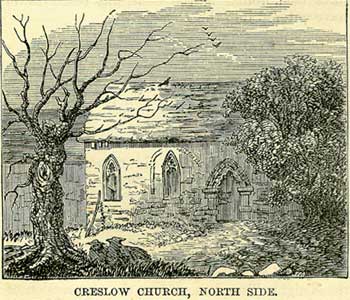

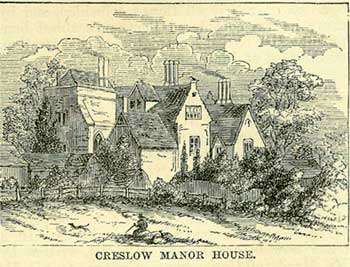

23rd JuneBorn: Bishop John Fell, 1625, Longworth; Gottfreid Wilhelm Leibnitz, historian, philosopher, 1646, Leipsic. 809 Died: Caius Flaminius, killed at the battle of Thrasimene, B. C. 217; Louis I of France (Le D'ebonnaire), 840; Mary Tudor, Duchess of Suffolk, 1533; Mark Akenside, poet, 1770; Catherine Macaulay (Mrs. Graham), historian, 1791, Binfaeld; James Mill, author of the History of India, &c., 1836, Kensington; Lady Hester Stanhope, 1839, Lebanon; Jolla Lord Campbell, Lord Chancellor of England, 1861. Feast Day: St. Etheldreda, or Audry, virgin and abbess of Ely, 679. St. Mary of Oignies, 1213. MRS. MACAULAYThere was a Macaulay's History of England long before Lord Macaulay's was heard of; and in its day a famous history it was. The first volume appeared in 1763 and the fifth in 1771, and the five quartos sold rapidly, and were replaced by two or three editions in octavo. It was entitled: The History of England from the Accession of James I to the Elevation of the House of Hanover, and the author was Mrs. Catharine Macaulay. The historian was the daughter of John Sawbridge, a gentleman resident at Ollantigh, near Wye, Kent, where she was born in 1733. From her girlhood she was an eager and promiscuous reader, her favourite books being, as she herself tells us, 'the histories which exhibit liberty in its most exalted state in the annals of the Roman and Greek Republics.' 'Liberty,' she says, 'became the object of a secondary worship in my delighted imagination.' She was married when in her twenth-seventh year to Dr. George Macaulay, a London physician, and excited by the conflict her enthusiastic republican opinions encountered in society, she set about writing her History, in which all characters and events were viewed through democratic spectacles. Female authorship was then more of a singularity than it is now, and her theme and her politics quickly raised her name into notoriety, and she was flattered and abused with equal vehemence. Her adversaries said she was horribly ugly (which she was not), and that in despair of admiration as a woman she was aspiring after glory as a man. Dr. Wilson, a son of the Bishop of Seder and Man, made her the present of a house and library in Bath worth £1,500, and, to the scandal of sober people, placed her statue in the chancel of St. Stephen's, Walbrook, London, of which he was rector. One of her heartiest admirers was John Wilkes, and in the popular furor for 'Wilkes and Liberty' her History greatly profited. She made a trip to Paris in 1777, and there received most grateful attentions from Franklin, Turgot, Marmontel, and other Liberals. Madame Roland in her Memoires says: 'It was my ambition to be for France what Mrs. Macaulay was for England.' In a dispute with Mrs. Macaulay, Dr. Johnson observed, 'You are to recollect, madam, that there is a monarchy in heaven;' to which she replied, 'If I thought so, sir, I should never wish to go there.' One day at her house he put on a grave face, and said, 'Madam, I am now become a convert to your way of thinking. I am convinced that all mankind are upon an equal footing; and, to give you an unquestionable proof, madam, that I am in earnest, here is a very sensible, civil, well-behaved fellow-citizen, your footman; I desire that he may be allowed to it down and dine with us.' 'I thus,' relates the doctor, 'shewed her the absurdity of the levelling doctrine. She has never liked me since. Your levellers wish to level down as far as them-selves; but they cannot bear levelling up to themselves.' Dr. Macaulay died in 1778, and shortly after Mrs. Macaulay married Mr. Graham, a young Scotchman, a brother of the noted quack of the same name. The disparity of their years exposed her to much ridicule, and so offended Dr. Wilson, that he removed her statue from St. Stephen's, to the great satisfaction of his parishioners, who contemplated raising a motion in the ecclesiastical courts concerning it. She had corresponded for some years with Washington, and in 1785, accompanied by Mr. Graham, she made a voyage to America, and spent three weeks in his society at Mount Vernon. On her return, she retired to a country-house in Leicestershire, where she died in 1791, aged 58. In addition to her History, Mrs. Macaulay was an active pamphleteer on politics, morals, and metaphysics, and always commanded a fair share of public attention. The History is sometimes met with at this day on the second-hand book-stalls, selling at little more than the price of waste paper. It is written in a vivacious style, but embodies no original thought or research, and is neither better nor worse than a series of republican harangues, in which the facts of English history under the Stuarts are wrought up from books which may be found in every gentle-man's library. JAMES MILLThough in a high degree romantic and wonderful, about no portion of their history do Englishmen shew less interest than in that which relates their struggles and conquests in India. On scarcely any matter is the attention of the House of Commons yielded less willingly than on Indian affairs. The reasons for this apathy may perhaps be traced to the complete division existing between the Hindoo and Englishman in race, mind, religion, and manners; and to the multitude of diverse tribes and nations who crowd Hindostan, turning India into a mere geographical expression, and complicating its history in a way to which even German history affords but a faint resemblance. We may imagine how all this might have been changed had the peninsula of Hindostan, like China, been ruled by one emperor, whose power Britain had sapped and overthrown. Instead of this the great drama is diffused in a myriad of episodes, and that unity is lost by which alone popular interest can be enthralled. Until James Mill published his History of British India, in 1818, any one who wished to attain the truth concerning most parts of that history had to seek for it in a chaos of books and documents. It was Mill's merit out of that chaos to evolve order. Many who have opened Mill's history for amusement, have closed it in weariness; but Mill made no attempt at brilliancy, and was only careful to describe events accurately and clearly. From the first openings of intercourse with India to the establishment of the East India Company, in the reign of Queen Anne, down to the end of the Mahratta war in 1805, he ran a straight, broad, and firm road through what had before been a jungle of hear-say, and voluminous and confused authorities. Mill was no mere compiler. He was a hard thinker and a philosopher; he thoroughly absorbed his matter, and reproduced it from his brain in a masterly digest, which has won the praise of all whose business it has been to consult him with serious purpose. James Mill was the son of a shoemaker and small farmer, and was born at Montrose, on the 6th of April 1773. He was a thoughtful lad, and Sir John Stuart, of Fettercairn, unwilling that his talents should be hidden, sent him to Edinburgh University, with the purpose of educating him for a minister in the Scottish Church. Mill, however, had little inclination for the pulpit, and Dugald Stewart's lectures confirmed his taste for literature and philosophy in preference to theology. Long afterwards, in writing to a friend, he said, 'The taste for the studies which have formed my favourite pursuits, and which will be so to the end of my life, I owe to Dugald Stewart.' For some years he acted as a tutor or teacher, and in 1800, when in London, he accepted the editorship of The Literary Journal. This paper was a failure, but he soon secured other work, and for twenty years supported himself by writing for magazines and newspapers. Shortly after coming to London he married. In 1806 was born his celebrated son, John Stuart Mill, whose education, as well as that of eight other sons and daughters, he conducted. About 1806 he commenced the History of British India in the hours he could rescue from business, and in twelve years completed and gave it to the world in three quarto volumes. In the course of the history, he had meted out censure freely and honestly to the East India Company; but so highly were the directors impressed with the merits of the work, that in the spring of 1819 they appointed Mill to manage their finances, and subsequently their entire correspondence with India. In possession of affluence, Mill's pen was active as ever, his favourite themes being political economy and metaphysics. He was the intimate friend and constant visitor of Jeremy Bentham; their opinions on nearly all things coincided, and by many he was considered Bentham's ablest lieutenant. Mill died at Kensington, of consumption, on the 23rd of June 1836. THE BOOK-FISH On the 23rd of June 1626, a cod-fish was brought to Cambridge market, which, upon being opened, was found to contain a book in its maw or stomach. The book was much soiled, and covered with slime, though it had been wrapped in a piece of sail-cloth. It was a duodecimo work written by one John Frith, comprising several treatises on religious subjects. In a letter now in the British Museum, written by Mr. Mead, of Christchurch College, to Sir M. Stuteville, the writer says: I saw all with mine own eyes, the fish, the maw, the piece of sail-cloth, the book, and observed all I have written; only I saw not the opening of the fish, which not many did, being upon the fish-woman's stall in the market, who first cut off his head, to which the maw hanging, and seeming much stuffed with somewhat, it was searched, and all found as aforesaid. He that had had his nose as near as I yester morning, would have been persuaded there was no imposture here without witness. The fish came from Lynn. The treatises contained in this book were written by Frith when in prison. Strange to say, he had been long confined in a fish cellar at Oxford, where many of his fellow-prisoners died from the impure exhalations of unsound salt fish. He was removed from thence to the Tower, and in 1533 was burned at the stake for his adherence to the reformed religion. The authorities at Cambridge reprinted the work, which had been completely forgotten, till it turned up in this strange manner. The reprint is entitled VoxPiscis, or the Book-Fish, and is adorned with a woodcut representing the stall in Cambridge market, with the fish, book, and knife. It also contains a few very feeble undergraduate jokes on the occasion; one is quite enough as a specimen of Cambridge wit at the period. 'A young scholar, who had, in a stationer's shop, peeped into the title of the Civil Law, then viewing this unconcocted book in the cod-fish, made a quibble thereupon; saying that it might have been found in the Code, but could never have entered into the Digest.' CRESLOW PASTURES. A GHOST STORYThe ancient manor of Creslow, which lies about half way between Aylesbury and Winslow, was granted by Charles II to Thomas, first Lord Clifford of Chudleigh, on the 23rd of June 1673, and has continued ever since the property of his successors. From possessing a fine old manor-house and the remains of an ancient church, as well as from historic associations, Creslow is not undeserving of notice. In the reign of Edward the Confessor, this manor was held by Aluren, a female, from whom it passed at the Conquest to Edward Sarisberi, a Norman lord. 'About the year 1120,' says Browne Willis, 'it was given to the Knights Templars, and on the suppression of that community, it passed to the Knights Hospitallers, from whom, at the dissolution of monasteries, it passed to the Crown. From this time till it passed to Lord Clifford, Creslow Manor was used as feeding ground for cattle for the royal household; and it is remarkable that nearly the whole of this manor, containing more than 850 acres, has been pasture land from the time of the Domesday survey, and the cattle now fed here are among the finest in the kingdom. While Creslow pastures continued in possession of the Crown, they were committed to the custody of a keeper. In 1596, James Quarles, Esq. Chief Clerk of the Royal Kitchen, was keeper of Creslow pastures. He was succeeded by Benett Mayne, a relative of the regicide, who was succeeded in 1634 by the regicide Cornelius Holland. This Cornelius Holland, whose father died insolvent in the Fleet, was 'a Poore boy in court waiting on Sir Henry Vane,' by whose interest he was appointed by Charles I keeper of Creslow pastures. He subsequently deserted the cause of his royal patron, and was rewarded by the Parliament with many lucrative posts. He entered the House of Commons in 1642, and after taking a very prominent part against the king, signed his death-warrant. He became so wealthy that, though he had ten children, he gave a daughter on her marriage £5,000, equal to ten times that sum at the present day. He is traditionally accused of having destroyed or dismantled many of the churches in the neighbourhood of Creslow. At the Restoration, being absolutely excepted from the royal amnesty, he escaped execution only by flying to Lausanne, where, says Noble, 'he ended his days in universal contempt.'  Creslow, though once a parish with a fair proportion of inhabitants, now contains only the manor-house, and the remains of an ancient church. Originally the church consisted of a chancel, nave, and tower; but the present building, which is used as a coach-house, constituted apparently only the nave. It is forty-four feet long, and twenty-four feet wide, and built of hewn stone, though most other churches in the county are composed of rubble. The south wall, which contains the entrance to the coach-house, has been sadly mutilated. The north wall remains in tolerable preservation, and presents many features of interest. The door-way, which is of the Norman, or very early English period, is decorated with the billet and zigzag ornaments. The present windows, which have evidently superseded others of an earlier date, belong to the decorated style, and consisted each of two trefoil-headed lights divided by a chamfered mullion. The boundary of the churchyard is not known, but the ground all round the church has been used for sepulture. A stone coffin, which is said to have been taken from the floor of the church, is now used, turned upside down and cracked through the middle, as a paving stone near the west door of the mansion. From the quantity of human remains found about the church, it is evident that the interments here have been unusually numerous for a village cemetery. But this is accounted for by the fact that the Hospitallers, for their valiant exploits at the siege of Ascalon, were rewarded by Pope Adrian IV with the privilege of exemption from all public interdicts and excommunications, so that in times of any national interdict, when all other churches were closed, the noble and wealthy would seek, at any cost or inconvenience, interment for their friends where the rites of sepulture could be duly celebrated. Here, then, in this privileged little cemetery, not only were interred many a puissant knight of St. John, and their dependents, but some of the proudest and wealthiest barons of the land. I do love these ancient ruins; We never tread upon them but we set Our foot upon some reverend history; And questionless here in this open court, Which now lies naked to the injuries Of stormy weather, some men lie interred Loved the church so well, and gave so largely to 't, They thought it should have canopied their bones Till Doomsday. But all things have an end: Churches and cities, which have diseases like to men, Must have like death that we have.  The mansion, though diminished in size and beauty, is still a spacious and handsome edifice. It is a picturesque and venerable looking building with numerous gables and ornamental chimneys, some ancient mullioned windows, and a square tower with octagonal turret. The walls of the tower are of stone, six feet thick; the turret is forty-three feet high, with a newal staircase and loopholes. Some of the more interesting objects within the house are the ground room in the tower, a large chamber called the banqueting room, with vaulted timber roof; a large oak door with massive hinges, and locks and bolts of a peculiar construction; and various remains of sculpture and carving in different parts of the house. Two ancient cellars, called 'the crypt' and 'the dungeon,' deserve special attention. The crypt, which is excavated in the solid limestone rock, is entered by a flight of stone steps, and has but one small window to admit light and air. It is about twelve feet square, and its roof, which is a good specimen of light Gothic vaulting, is supported by arches springing from four columns, groined at their intersections, and ornamented with carved flowers and bosses, the central one being about ten feet from the floor. The 'dungeon,' which is near the crypt, is entered by a separate flight of stone steps, and is a plain rectangular building, eighteen feet long, eight and a half wide, and six in height. The roof, which is but slightly vaulted, is formed of exceedingly massive stones. There is no window, or external opening into this cellar, and, for whatever purpose intended, it must have always been a gloomy, darksome vault, of extreme security. It now contains several skulls and other human bones-some of the thigh-bones, measuring more than nineteen inches, must have belonged to persons of gigantic stature. This dungeon had formerly a subterranean communication with the crypt, from which there was a newal staircase to a chamber above, which still retains the Gothic doorway, with hood-moulding resting on two well sculptured human heads, with grotesque faces. This chamber, which is supposed to have been the preceptor's private room, has also a good Gothic window of two lights, with head tracery of the decorated period. This is the haunted chamber. For Creslow, like all old manor-houses, has its ghost story. But the ghost is not a knight-templar or knight of St. John, but a lady. Seldom, indeed, has she been seen, but often has she been heard, only too plainly, by those who have ventured to sleep in this room, or enter after midnight. She appears to come from the crypt or dungeon, and always enters this room by the Gothic door. After entering, she is heard to walk about, sometimes in a gentle, stately manner, apparently with a long silk train sweeping the floor-sometimes her motion is quick and hurried, her silk dress rustling violently, as if she were engaged in a desperate struggle. As these mysterious visitations had anything but a somniferous effect on wearied mortals, this chamber, though furnished as a bedroom, was seldom so used, and was never entered by servants without trepidation and awe. Occasionally, however, someone was found bold enough to dare the harmless noises of the mysterious intruder, and many are the stories respecting such adventures. The following will suffice as a specimen, and may be depended on as authentic. About the year 1850, a gentleman who resided some miles distant, rode over to a dinner-party, and as the night became exceedingly dark and rainy, he was urged to stay over the night, if he had no objection to sleep in a haunted chamber. The offer of a bed in such a room, so far from deterring him, induced him at once to accept the invitation. He was a strong-minded man, of a powerful frame, and undaunted courage, and entertained a sovereign contempt for all ghost stories. The room was prepared for him. He would neither have a fire nor a burning candle, but requested a box of lucifers, that he might light a candle if he wished. Arming himself, in jest, with a cutlass and a brace of pistols, he took a serio-comic farewell of the family, and entered his formidable dormitory. Morning came, and ushered in one of those glorious autumnal days which often succeed a night of soaking rain. The sun shone brilliantly on the old manor-house. Every loop-hole and cranny in the tower was so penetrated by his rays, that the venerable owls, that had long inherited its roof, could scarcely find a dark corner to doze in, after their nocturnal labours. The family and their guests assembled in the breakfast room, and every countenance seemed cheered and brightened by the loveliness of the morning. They drew round the table, when lo! the host remarked that the tenant of the haunted chamber was absent. A servant was sent to summon him to breakfast, but he soon returned, saying he had knocked loudly at his door but received no answer, and that a jug of hot water left at his door was still standing there unused. On hearing this, two or three gentlemen ran up to his room, and after knocking at his door, and receiving no answer, they opened it, and entered the room. It was empty. The sword and the pistols were lying on a chair near the bed, which had been used, but its occupant was gone. The ghost had put him to flight. Inquiry was made of the servants: they had neither seen nor heard anything of him, but on first coming down in the morning they found an outer door unfastened. As he was a county magistrate, it was now supposed that he was gone to attend the board which met that morning at an early hour. The gentlemen proceeded to the stable, and found his horse was still there. This by no means diminished the mystery. The party sat down to breakfast, not without feelings of perplexity, mingled with no little curiosity. Many strong conjectures were discussed; and just as a lady suggested dragging the fish-ponds, in walked the knight-errant! Had the ghost herself appeared at that moment, she could scarcely have caused more consternation. Such was the general eagerness for an account of the knight's adventures, that, before beginning his breakfast, he promised to relate fully and candidly all the particulars of the case. Having entered my room,' said he, 'I locked and bolted both doors, carefully examined the whole room, and satisfied myself that there was no living creature in it but myself, nor any entrance but those I had secured. I got into bed, and, with. the conviction I should sleep as usual till six in the morning, I was soon lost in a comfortable slumber. Suddenly I was aroused, and on raising my head to listen, I heard a sound certainly resembling the light, soft tread of a lady's footstep, accompanied with the rustling as of a silk gown. I sprang out of bed and lighted a candle. There was nothing to be seen, and nothing now to be heard. I carefully examined the whole room. I looked under the bed, into the fire-place, up the chimney, and at both the doors, which were fastened as I had left them. I looked at my watch, and found it was a few minutes past twelve. As all was now perfectly quiet, I extinguished the candle, and entered my bed, and soon fell asleep. I was again aroused. The noise was now louder than before. It appeared like the violent rustling of a stiff silk dress. I sprang out of bed, darted to the spot where the noise was, and tried to grasp the intruder in my arms. My arms met together, but enclosed nothing. The noise passed to another part of the room, and I followed it, groping near the floor, to prevent anything passing under my arms. It was in vain, I could feel nothing-the noise had passed away through the Gothic door, and all was still as death! I lighted a candle, and examined the Gothic door, and there I saw-the old monks' faces grinning at my perplexity; but the door was shut and fastened, just as I had left it. I again examined the whole room, but could find nothing to account for the noise. I now left the candle burning, though I never sleep comfortably with a light in my room. I got into bed, but felt, it must be acknowledged, not a little perplexed at not being able to detect the cause of the noise, nor to account for its cessation when the candle was lighted. While ruminating on these things, I fell asleep, and began to dream about murders, and secret burials, and all sorts of horrible things; and just as I fancied myself knocked down by a knight-templar I awoke, and found the sun shining so brightly, that I thought a walk would be far more refreshing than another disturbed sleep; so I dressed and went out before the servants were down. Such, then, is a full, true, and particular account of my night's adventure, and, though I cannot account for the noises in the haunted chamber, I am still no believer in ghosts. Doubtless there are no ghosts; Yet somehow it is better not to move, Lest cold hands seize upon us from behind. DOBELL - THE FIRST ENGLISH REGATTALady Montague's description of a regatta, or fete held on the water, which she witnessed at Venice, stimulated the English people of fashion to have something of a similar kind on the Thames, and after much preparation and several disappointments, caused by unfavourable weather, the long expected show took place on the 23rd of June 1775. The programme, which was submitted to the public a month before, requested ladies and gentlemen to arrange their own parties, except those who should apply to the managers of the Regatta for seats in the barges lent by the several City Companies for the occasion. The rowers were to be uniformly dressed in accordance with the three marine colours-white, red, and blue. The white division was directed to take position at the two arches on each side of the centre arch of Westminster Bridge. The red division at the four arches next the Surrey shore; and the blue at the four on the Middlesex side of the river. The company were to embark between five and six o'clock in the evening, and at seven all the boats were to move up the river to Ranelagh in procession. The marshal of the white, in a twelve-oared barge, leading his division; the marshals of the red and blue, with their respective divisions, following at intervals of three minutes between each. Early in the afternoon, the river, from London Bridge to Millbank, was crowded with pleasure boats, and scaffolds, gaily decorated with flags, were erected wherever a view of the Thames could be obtained. Half-a-guinea was asked for a seat in a coal-barge; and vessels fitted for the purpose drove a brisk trade in refreshments of various kinds. The avenues to Westminster Bridge were covered with gaming-tables, and constables guarded every passage to the water, taking from half-a-crown to one penny for liberty to pass. Soon after six o'clock, concerts were held under the arches of Westminster Bridge; and a salute of twenty-one cannons announced the arrival of the Lord Mayor. A race of wager-boats followed, and then the procession moved in a picturesque irregularity to Ranelagh. The ladies were dressed in white, the gentlemen in undress frocks of all colours; about 200,000 persons were supposed to be on the river at one time. The company arrived at Ranelagh at nine o'clock, where they joined those who came by land in a new building, called the Temple of Neptune. This was a temporary octagon, lined with stripes of white, red, and blue cloth, and having lustres hanging between each pillar. Supper and dancing followed, and the entertainment did not conclude till the next morning. Many accidents occurred when the boats were returning after the fete, and seven persons were unfortunately drowned. |