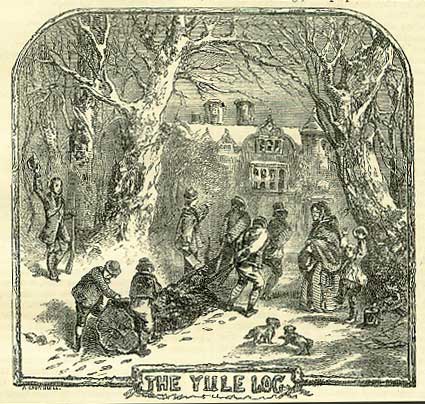

24th December (part 1)Born: Galba, Roman emperor, 3 B. C.; John, King of England, 1166, Oxford; William Warburton, bishop of Gloucester, 1698, Newark; George Crabbe, poet, 1754, Aldborough; Eugene Scribe, French dramatist, 1791, Paris. Died: George of Cappadocia, noted Archbishop, slain at Alexandria, 361 A.D.; Thomas Beaufort, Duke of Exeter, 1426, Bury St. Edmunds; Vases de Gama, celebrated Portuguese navigator, 1525, Cochin, in Malabar; Madame de Geniis, popular authoress, 1830, Paris; Davies Gilbert, antiquarian and man of science, 1839, Eastbourne, Sussex; Archdeacon Henry John Todd, editor of Johnson's Dictionary, &c., 1845, Settrington, Yorkshire; Dr. John Ayrton Paris, chemist, 1856, London; Hugh Miller, geologist, 1856, Portobello. Feast Day: St. Gregory of Spoleto, martyr, 304. Saints Thrasilla and Emiliana, virgins. Christmas EveThe eves or vigils of the different ecclesiastical festivals throughout the year are, according to the strict letter of canonical rule, times of fasting and penance; but in several instances, custom has appropriated them to very different purposes, and made them, seasons of mirth and jollity. Such is the case with All-Saints'Eve, and perhaps even more so with Christmas Eve, or the evening before Christmas Day. Under the latter head, or 25th of December, will be found a special history of the great Christian festival; though the observances of both days are so intertwined together, that it becomes almost impossible to state, with precision, the ceremonies which are peculiar to each. We shall, however, do the best we can in the circumstances, and endeavor, under the 24th of December, to restrict ourselves to an account of the popular celebrations and customs which characterize more especially the eve of the Nativity. With Christmas Eve, the Christmas holidays may practically be said to commence, though, according to ecclesiastical computation, the festival really begins on the 16th of December, or the day which is distinguished in the calendar as O. Sapientia, from the name of an anthem, sung during Advent. It is proper, however, to state that there seems to be a discrepancy of opinion on this point, and that, in the judgment of some, the true Christmas festival does not commence till the evening before Christmas Day. The season is held to terminate on 1st of February, or the evening before the Purification of the Virgin (Candlemas Day), by which date, according to the ecclesiastical canons, all the Christmas decorations must be removed from the churches. In common parlance, certainly, the Christmas holidays comprehend a period of nearly a fortnight, commencing on Christmas Eve, and ending on Twelfth Day. The whole of this season is still a jovial one, abounding in entertainments and merry-makings of all sorts, but is very much changed from what it used to be with our ancestors in feudal times, when it was an almost unintermitted round of feasting and jollity. For a picture of Christmas Eve, in the olden time, we can desire none more graphic than that furnished by Sir Walter Scott in Marmion: On Christmas Eve the bells were rung; On Christmas Eve the mass was sung; That only night, in all the year, Saw the stoled priest the chalice rear. The damsel donned her kirtle sheen; The hall was dressed with holly green; Forth to the wood did merry-men go, To gather in the mistletoe. Then opened wide the baron's hall To vassal, tenant, serf, and all; Power laid his rod of rule aside, And Ceremony doffed his pride. The heir, with roses in his shoes, That night might village partner choose. The lord, underogating, share The vulgar game of ' post and pair. All hailed, with uncontrolled delight, And general voice, the happy night, That to the cottage, as the crown, Brought tidings of salvation down! The fire, with well-dried logs supplied, Went roaring up the chimney wide; The huge hall-table's oaken face, Scrubbed till it shone, the day to grace, Bore then upon its massive board No mark to part the squire and lord. Then was brought in the lusty brawn, By old blue-coated serving-man; Then the grim boar's-head frowned on high, Crested with bays and rosemary. Well can the green-garbed ranger tell, How, when, and where the monster fell What dogs before his death he tore, And all the baiting of the boar. The wassail round in good brown bowls, Garnished with ribbons, blithely trowls. There the huge sirloin reeked: hard by Plum-porridge stood, and Christmas-eye; Nor failed old Scotland to produce, At such high-tide, her savoury goose. Then came the merry masquers in, And carols roared with blithesome din If unmelodious was the song, It was a hearty note, and strong. Who lists may in their mumming see Traces of ancient mystery; White shirts supplied the masquerade, And smutted cheeks the visors made; But, oh! what masquers, richly dight, Can boast of bosoms half so light! England was merry England, when Old Christmas brought his sports again. 'Twas Christmas broached the mightiest ale; 'Twas Christmas told the merriest tale A Christmas gambol oft could cheer The poor man's heart through half the year. To investigate the origin of many of our Christmas customs, it becomes necessary to wander far back into the regions of past time, long ere Julius Caesar had set his foot on our shores, or St. Augustine preached the doctrines of Christianity to the men of Kent. We have frequently, in the course of this work, had occasion to remark on the numerous traces still visible in popular customs of the old pagan rites and ceremonies. These, it is needless here to repeat, were extensively retained after the conversion of Britain to Christianity, partly because the Christian teachers found it impossible to wean their converts from their cherished superstitions and observances, and partly because they themselves, as a matter of expediency, ingrafted the rites of the Christian religion on the old heathen ceremonies, believing that thereby the cause of the Cross would be rendered more acceptable to the generality of the populace, and thus be more effectually promoted. By such an amalgamation, no festival of the Christian year was more thoroughly characterized than Christmas; the festivities of which, originally derived from the Roman Saturnalia, had afterwards been intermingled with the ceremonies observed by the British Druids at the period of the winter-solstice, and at a subsequent period became incorporated with the grim mythology of the ancient Saxons. Two popular observances belonging to Christmas are more especially derived from the worship of our pagan ancestors-the hanging up of the mistletoe, and the burning of the Yule log. As regards the former of these practices, it is well known that, in the religion of the Druids, the mistletoe was regarded with the utmost veneration, though the reverence which they paid to it seems to have been restricted to the plant when found growing on the oak-the favorite tree of their divinity Tutanes-who appears to have been the same as the Phenician god Baal, or the sun, worshiped under so many different names by the various pagan nations of antiquity. At the period of the winter-solstice, a great festival was celebrated in his honour, as will be found more largely commented on under our notice of Christmas Day. When the sacred anniversary arrived, the ancient Britons, accompanied by their priests, the Druids, sallied forth with great pomp and rejoicings to gather the mystic parasite, which, in addition to the religious reverence with which it was regarded, was believed to possess wondrous curative powers. When the oak was reached on which the mistletoe grew, two white bulls were bound to the tree, and the chief Druid, clothed in white (the emblem of purity), ascended, and, with a golden knife, cut the sacred plant, which was caught by another priest in the folds of his robe. The bulls, and often also human victims, were then sacrificed, and various festivities followed. The mistletoe thus gathered, was divided into small portions, and distributed among the people, who hung up the sprays over the entrances to their dwellings, as a propitiation and shelter to the sylvan deities during the season of frost and cold. These rites in connection with the mistletoe, were retained throughout the Roman dominion in Britain, and also for a long period under the sovereignty of the Jutes, Saxons, and Angles. The following legend regarding the mistletoe, from the Scandinavian mythology, may here be introduced: Balder, the god of poetry and eloquence, and second son of Odin and Friga, communicated one day to his mother a dream which he had had, intimating that he should die. She (Friga), to protect her son from such a contingency, invoked all the powers of nature-fire, air, earth, and water, as well as animals and plants-and obtained an oath from them that they should do Balder no hurt. The latter then went and took his place amid the combats of the gods, and fought without fear in the midst of showers of arrows. Loake, his enemy, resolved to discover the secret of Balder's invulnerability, and, accordingly, disguising himself as an old woman, he addressed himself to Friga with complimentary remarks on the valour and good-fortune of her son. The goddess replied that no substance could injure him, as all the productions of nature had bound themselves by an oath to refrain from doing him any harm. She added, however, with that awkward simplicity which appears so often to characterise mythical personages, that there was one plant which, from its insignificance, she did not think of conjuring, as it was impossible that it could inflict any hurt on her son. Loake inquired the name of the plant in question, and was informed that it was a feeble little shoot, growing on the bark of the oak, with scarcely any soil. Then the treacherous Loake ran and procured the mistletoe, and, having entered the assembly of the gods, said to the blind Heda: 'Why do you not contend with the arrows of Balder? 'Heda replied: I am blind, and have no arms.' Loake then presented him with an arrow formed from the mistletoe, and said: 'Balder is before thee.' Heda shot, and Balder fell pierced and slain. The mistletoe, which has thus so many mystic associations connected with it, is believed to be propagated in its natural state by the misselthrush, which feeds upon its berries. It was long thought impossible to propagate it artificially, but this object has been attained by bruising the berries, and by means of their viscidity, causing them to adhere to the bark of fruit-trees, where they readily germinate and take root. The growth of the mistletoe on the oak is now of extremely rare occurrence, but in the orchards of the west-midland counties of England, such as the shires of Gloucester and Worcester, the plant flourishes in great frequency and luxuriance on the apple-trees. Large quantities are annually cut at the Christmas season, and dispatched to London and other places, where they are extensively used for the decoration of houses and shops. The special custom connected with the mistletoe on Christmas Eve, and an h indubitable relic of the days of Druidism, handed down through a long course of centuries, must he familiar to all our readers. A branch of the mystic plant is suspended from the wall or ceiling, and any one of the fair sex, who, either from inadvertence, or, as possibly may be insinuated, on purpose, passes beneath the sacred spray, incurs the penalty of being then and there kissed by any lord of the creation who chooses to avail himself of the privilege.  The burning of the Yule log is an ancient Christmas ceremony, transmitted to us from our Scandinavian ancestors, who, at their feast of Juul, at the winter-solstice, used to kindle huge bonfires in honour of their god Thor. The custom, though sadly shorn of the 'pomp and circumstance' which formerly attended it, is still maintained in various parts of the country. The bringing in and placing of the ponderous block on the hearth of the wide chimney in the baronial hall was the most joyous of the ceremonies observed on Christmas Eve in feudal times. The venerable log, destined to crackle a welcome to all-comers, was drawn in triumph from its resting-place at the feet of its living brethren of the woods. Each wayfarer raised his hat as it passed, for he well knew that it was full of good promises, and that its flame would burn out old wrongs and hearthurnings, and cause the liquor to bubble in the wassail-bowl, that was quaffed to the drowning of ancient feuds and animosities. So the Yule-log was worthily honoured, and the ancient bards welcomed its entrance with their minstrelsy. The following ditty, appropriate to such an occasion, appears in the Sloane Manuscripts. It is supposed to be of the time of Henry VI: WELCOME YULE Welcome be thou, heavenly King, Welcome born on this morning, Welcome for whom we shall sing, Welcome Yule, Welcome be ye Stephen and John, Welcome Innocents every one, Welcome Thomas Martyr one, Welcome Yule. Welcome be ye, good New Year, Welcome Twelfth Day, both in fere, Welcome saints, loved and dear, Welcome Yule. Welcome be ye, Candlemas, Welcome be ye, Queen of Bliss, Welcome both to more and less, Welcome Yule. Welcome be ye that are here, Welcome all, and make good cheer, Welcome all, another year, Welcome Yule. And here, in connection with the festivities on Christmas Eve, we may quote Herrick's inspiriting stanzas: Come bring with a noise, My merry, merry boys, The Christmas log to the firing, While my good dame she Bids ye all be free, And drink to your heart's desiring. With the last year's brand Light the new block, and, For good success in his spending, On your psalteries play That sweet luck may Come while the log is a teending. Drink now the strong beer, Cut the white loaf here, The while the meat is a shredding; For the rare mince-pie, And the plums stand by, To fill the paste that's a kneading. The allusion at the commencement of the second stanza, is to the practice of laying aside the half-consumed block after having served its purpose on Christmas Eve, preserving it carefully in a cellar or other secure place till the next anniversary of Christmas, and then lighting the new log with the charred remains of its predecessor. The due observance of this custom was considered of the highest importance, and it was believed that the preservation of last year's Christmas log was a most effectual security to the house against fire. We are further informed, that it was regarded as a sign of very bad-luck if a squinting person entered the hall when the log was burning, and a similarly evil omen was exhibited in the arrival of a bare-footed person, and, above all, of a flat-footed woman! As an accompaniment to the Yule log, a candle of monstrous size, called the Yule Candle, or Christmas Candle, shed its light on the festive-board during the evening. Brand, in his Popular Antiquities, states that, in the buttery of St. John's College, Oxford, an ancient candle socket of stone still remains, ornamented with the figure of the Holy Lamb. It was formerly used for holding the Christmas Candle, which, during the twelve nights of the Christmas festival, was burned on the high-table at supper. In Devonshire, the Yule log takes the form of the ashton fagot, and is brought in and burned with great glee and merriment. The fagot is composed of a bundle of ash-sticks bound or hooped round with bands of the same tree, and the number of these last ought, it is said, to be nine. The rods having been cut a few days previous, the farm-labourers, on Christmas Eve, sally forth joyously, bind them together, and then, by the aid of one or two horses, drag the fagot, with great rejoicings, to their master's house, where it is deposited on the spacious hearth which serves as the fireplace in old-fashioned kitchens. Fun and jollity of all sorts now commence, the members of the household-master, family, and servants-seat themselves on the settles beside the fire, and all meet on terms of equality, the ordinary restraint characterizing the intercourse of master and servant being, for the occasion, wholly laid aside. Sports of various kinds take place, such as jumping in sacks, diving in a tub of water for apples, and jumping for cakes and treacle; that is to say, endeavoring, by springs (the hands being tied behind the back), to catch with the mouth a cake, thickly spread with treacle, and suspended from the ceiling. Liberal libations of cider, or egg-hot, that is, cider heated and mixed with eggs and spices, somewhat after the manner of the Scottish het-pint, are supplied to the assembled revellers, it being an acknowledged and time-honoured custom that for every crack which the bands of the ashton fagot make in bursting when charred through, the master of the house is bound to furnish a fresh bowl of liquor. To the credit of such gatherings it must be stated that they are characterized, for the most part, by thorough decorum, and scenes of inebriation and disorder are seldom witnessed. One significant circumstance connected with the vigorous blaze which roars up the chimney on Christmas Eve ought not to be forgotten. We refer to the practice of most of the careful Devonshire housewives, at this season, to have the kitchen-chimney swept a few days previously, so as to guard against accidents from its taking fire. In Cornwall, as we are informed by a contributor to Notes and Queries, the Yule log is called 'the mock,' and great festivities attend the burning of it, including the old ceremony of lighting the block with a brand preserved from the fire of last year. We are informed also that, in the same locality, Christmas Eve is a special holiday with children, who, on this occasion, are allowed to sit up till midnight and' drink to the mock.' Another custom in Devonshire, still practiced, we believe, in one or two localities on Christmas Eve, is for the farmer with his family and friends, after partaking together of hot cakes and cider (the cake being dipped in the liquor previous to being eaten), to proceed to the orchard, one of the party bearing hot cake and cider as an offering to the principal apple-tree. The cake is formally deposited on the fork of the tree, and the cider thrown over the latter, the men firing off guns and pistols, and the women and girls shouting: Bear blue, apples and pears enow, Barn fulls, bag fulls, sack fulls. Hurrah! hurrah! hurrah! A similar libation of spiced-ale used to be sprinkled on the orchards and meadows in Norfolk; and the author of a very ingenious little work, The Christmas Book: Christmas in the Olden Time: Its Customs and their Origin (London, 1859) published some years ago, states that he has witnessed a ceremony of the same sort, in the neighborhood of the New Forest in Hampshire, where the chorus sung was - Apples and pears with right good corn, Come in plenty to every one, Eat and drink good cake and not ale, Give Earth to drink and she'll not fail. From a contributor to Notes and Queries, we learn that on Christmas Eve, in the town of Chester and surrounding villages, numerous parties of singers parade the streets, and are hospitably entertained with meat and drink at the different houses where they call. The farmers of Cheshire pass rather an uncomfortable season at Christmas, seeing that they are obliged, for the most part, during this period, to dispense with the assistance of servants. According to an old custom in the county, the servants engage themselves to their employers from New-Year's Eve to Christmas Day, and then for six or seven days, they leave their masters to shift for themselves, while they (the servants) resort to the towns to spend their holidays. On the morning after Christmas Day hundreds of farm-servants (male and female) dressed in holiday attire, in which all the hues of the rainbow strive for the mastery, throng the streets of Chester, considerably to the benefit of the tavern-keepers and shop-keepers. Having just received their year's wages, extensive investments are made by them in smock frocks, cotton dresses, plush-waistcoats, and woolen shawls. Dancing is merrily carried on at various public-houses in the evening. In the whole of this custom, a more vivid realization is probably presented than in any other popular celebration at Christmas, of the precursor of these modern jovialities-the ancient Roman Saturnalia, in which the relations of master and servant were for a time reversed, and universal license prevailed. Among Roman Catholics, a mass is always celebrated at midnight on Christmas Eve, another at daybreak on Christmas Day, and a third at a subsequent hour in the morning. A beautiful phase in popular superstition, is that which represents a thorough prostration of the Powers of Darkness as taking place at this season, and that no evil influence can then be exerted by them on mankind. The cock is then supposed to crow all night long, and by his vigilance to scare away all malignant spirits. The idea is beautifully expressed by Shakespeare, who puts it in the mouth of Marcellus, in Hamlet: It faded on the crowing of the cock. Some say, that ever 'gainst that season comes Wherein our Saviour's birth is celebrated, The bird of dawning singeth all night long: And then, they say, no spirit can walk abroad; The nights are wholesome; then no planets strike, No fairy takes, nor witch hath power to charm; So hallow'd and so gracious is the time. A belief was long current in Devon and Cornwall, and perhaps still lingers both there and in other remote parts of the country, that at mid-night, on Christmas Eve, the cattle in their stalls fall down on their knees in adoration of the infant Saviour, in the same manner as the legend reports them to have done in the stable at Bethlehem. Bees were also said to sing in their hives at the same time, and bread baked on Christmas Eve, it was averred, never became mouldy. All nature was thus supposed to unite in celebrating the birth of Christ, and partake in the general joy which the anniversary of the Nativity inspired. THE CHRISTMAS-TREE: CHRISTMAS EVE IN GERMANY AND AMERICAIn Germany, Christmas Eve is for children the most joyous night in the year, as they then feast their eyes on the magnificence of the Christmas-tree, and rejoice in the presents which have been provided for them on its branches by their parents and friends. The tree is arranged by the senior members of the family, in the principal room of the house, and with the arrival of evening the children are assembled in an adjoining apartment. At a given signal, the door of the great room is thrown open, and in rush the juveniles eager and happy. There, on a long table in the center of the room, stands the Christmas-tree, every branch glittering with little lighted tapers, while all sorts of gifts and ornaments are suspended from the branches, and possibly also numerous other presents are deposited separately on the table, all properly labeled with the names of the respective recipients. The Christmas-tree seems to be a very ancient custom in Germany, and is probably a remnant of the splendid and fanciful pageants of the middle ages. Within the last twenty years, and apparently since the marriage of Queen Victoria with Prince Albert, previous to which time it was almost unknown in this country, the custom has been introduced into England with the greatest success, and must be familiar to most of our readers. Though thoroughly an innovation on our old Christmas customs, and partaking, indeed, some-what of a prosaic character, rather at variance with the beautiful poetry of many of our Christmas usages, he would be a cynic indeed, who could derive no pleasure from contemplating the group of young and happy faces who cluster round the Christmas-tree. S. T. Colridge, in a letter from Ratzeburg, in North Germany, published in the Friend, and quoted by Hone, mentions the following Christmas customs as observed in that locality. Part of them seems to be derived from those ceremonies proper to St. Nicholas's Day, already described under 6th December. There is a Christmas custom here which pleased and interested me. The children make little presents to their parents, and to each other, and the parents to their children. For three or four months before Christmas, the girls are all busy, and the boys save up their pocket-money to buy these presents. What the present is to be, is cautiously kept secret; and the girls have a world of contrivances to conceal it-such as working when they are out on visits, and the others are not with them; getting up in the morning before day-light, &c. Then, on the evening before Christmas-day, one of the parlors is lighted up by the children, into which the parents must not go; a great yew-bough is fastened on the table at a little distance from the wall, a multitude of little tapers are fixed in the bough, but not so as to burn it till they are nearly consumed, and coloured paper, &c., hangs and flutters from the twigs. Under this bough the children lay out, in great order, the presents they mean for their parents, still concealing in their pockets what they intend for each other. Then the parents are introduced, and each presents his little gift; they then bring out the remainder, one by one, from their pockets, and present them with kisses and embraces. Where I witnessed this scene, there were eight or nine children, and the eldest daughter and the mother wept aloud for joy and tenderness; and the tears ran down the face of the father, and he clasped all his children so tight to his breast, it seemed as if he did it to stifle the sob that was rising within it. I was very much affected. The shadow of the bough and its appendages on the wall, and arching over on the ceiling, made a pretty picture; and then the raptures of the very little ones, when at last the twigs and their needles began to take fire and snap O! it was a delight to them! On the next day (Christmas-day), in the great parlor, the parents lay out on the table the presents for the children; a scene of more sober joy succeeds; as on this day, after an old custom, the mother says privately to each of her daughters, and the father to his sons, that which he has observed most praiseworthy, and that which was most faulty, in their conduct. Formerly, and still in all the smaller towns and villages throughout North Germany, these presents were sent by all the parents to some one fellow, who, in high-buskins, a white robe, a mask, and an enormous flax-wig, personates Knecht Rupert-i. e., the servant Rupert. On Christmas-night, he goes round to every house, and says that Jesus Christ, his Master, sent him thither. The parents and elder children receive him with great pomp and reverence, while the little ones are most terribly frightened. He then inquires for the children, and, according to the character which he hears from the parents, he gives them the intended presents, as if they came out of heaven from Jesus Christ. Or, if they should have been bad children, he gives the parents a rod, and in the name of his Master recommends them to use it frequently. About seven or eight years old, the children are let into the secret, and it is curious how faithfully they keep it. In the state of Pennsylvania, in North America, where many of the settlers are of German descent, Christmas Eve is observed with many of the ceremonies practiced in the Fatherland of the Old World. The Christmas-tree branches forth in all its splendor, and before going to sleep, the children hang up their stockings at the foot of the bed, to be filled by a personage bearing the name of Krishkinkle (a corruption of Christ-kindlein, or the Infant Christ), who is supposed to descend the chimney with gifts for all good children. If, however, any one has been naughty, he finds a birch-rod instead of sweetmeats in the stocking. This implement of correction is believed to have been placed there by another personage, called Pelsnichol, or Nicholas with the fur, in allusion to the dress of skins which he is supposed to wear. In this notion, a connection is evidently to be traced with the well-known legendary attributes of St. Nicholas, previously described, though the benignant character of the saint is in this instance woefully belied. It is further to be remarked, that though the general understanding is that Krishkinkle and Pelsnichol are distinct personages-the one the rewarder of good children, the other the punisher of the bad they are also occasionally represented as the same individual under different characters, the prototype of which was doubtless the charitable St. Nicholas. CHRISTMAS GAMES: SNAPDRAGONSome interesting particulars relative to the indoor diversions of our ancestors at Christmas, occur in the following passage quoted by Brand from a tract, entitled Round about our Coal-fire, or Christmas Entertainments, which was published in the early part of the last century.' The time of the year being cold and frosty, the diversions are within doors, either in exercise or by the fireside. Dancing is one of the chief exercises; or else there is a match at Blindman's Buff, or Puss in the Corner. The next game is Questions and Commands, when the commander may oblige his subjects to answer any lawful question, and make the same obey him instantly, under the penalty of being smutted [having the face blackened], or paying such forfeit as may be laid on the aggressor. Most of the other diversions are cards and dice.' From the above we gather that the sports on Christmas evenings, a hundred and fifty years ago, were not greatly dissimilar to those in vogue at the; present day. The names of almost all the pastimes then mentioned must be familiar to every reader, who has probably also participated in them himself, at some period of his life. Let us only add charades, that favorite amusement of modern drawing-rooms (and of these only the name, not the sport itself, was unknown to our ancestors), together with a higher spirit of refinement and delicacy, and we shall discover little difference between the juvenile pastimes of a Christmas-party in the reign of Queen Victoria, and a similar assemblage in the reign of Queen Anne or the first Georges.  One favorite Christmas sport, very generally played on Christmas Eve, has been handed down to us from time immemorial under the name of 'Snapdragon.' To our English readers this amusement is perfectly familiar, but it is almost unknown in Scotland, and it seems therefore desirable here to give a description of the pastime. A quantity of raisins are deposited in a large dish or bowl (the broader and shallower this is, the better), and brandy or some other spirit is poured over the fruit and ignited. The bystanders now endeavour, by turns, to grasp a raisin, by plunging their hands through the flames; and as this is somewhat of an arduous feat, requiring both courage and rapidity of action, a considerable amount of laughter and merriment is evoked at the expense of the unsuccessful competitors. As an appropriate accompaniment we introduce here; The Story of Snapdragon Here he comes with flaming bowl, Don't he mean to take his toll, Snip! Snap! Dragon! Take care you don't take too much, Be not greedy in your clutch, Snip! Snap! Dragon! With his blue and lapping tongue Many of you will be stung, Snip! Snap! Dragon! For he snaps at all that comes Snatching at his feast of plums, Snip! Snap! Dragon! But Old Christmas makes him come, Though he looks so fee! fa! fum! Snip! Snap! Dragon! Don't 'ee fear him, be but bold-- Out he goes, his flames are cold, Snip! Snap! Dragon! Whilst the sport of Snapdragon is going on, it is usual to extinguish all the lights in the room, so that the lurid glare from the flaming spirits may exercise to the full its weird-like effect. There seems little doubt that in this amusement we retain a trace of the fiery ordeal of the middle ages, and also of the Druidical fire-worship of a still remoter epoch. A curious reference to it occurs in the quaint old play of Lingua, quoted by Mr. Sandys in his work on Christmas: Memory. Oh, I remember this dish well; it was first invented by Pluto to entertain Proserpine withal. Phantastes. I think not so, Memory; for when Hercules had killed the flaming dragon of Hesperia, with the apples of that orchard he made this fiery meat; in memory whereof he named it Snap-dragon. Snapdragon, to personify him, has a 'poor relation' or 'country cousin,' who bears the name of Flapdragon. This is a favorite amusement among the common people in the western counties of England, and consists in placing a lighted candle in a can of ale or cider, and drinking up the contents of the vessel. This act entails, of course, considerable risk of having the face singed, and herein lies the essence of the sport, which may be averred to be a somewhat more arduous proceeding in these days of moustaches and long whiskers than it was in the time of our close-shaved grandfathers. |