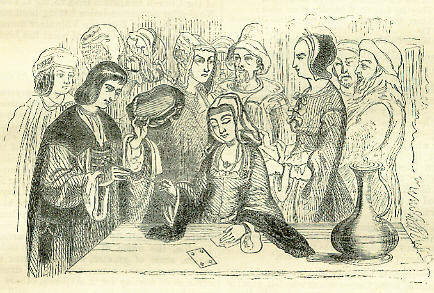

21st FebruaryBorn: Pierre du Bose, 1623, Bayeux; Mrs. Anne Grant, author of Letters from the Mountains, 1755, Glasgow. Died: Caius Caesar Agrippa, A.D. 4: James I (of Scotland), murdered, 1437, Perth; Pope Julius I, 1513; Henry Grey, duke of Suffolk, beheaded, 1555: Robert Southwell, poet, executed at Tyburn, 1595: Secretary John Thurloc, 1668, Lincoln's-inn; Benedict de Spinoza, philosopher, 1677; Pope Benedict XIII, 1730; Eugène de Beauharnois, Duke of Leuchtenberg, 1824, Munich; Rev. Robert Hall, Baptist preacher, 1831, Bristol; Charles Rossi, R.A., sculptor, 1839. Feast Day: Saints Daniel, priest, and Verde, virgin, martyrs, 344. St. Severianus, bishop of Scythopolis, martyr, about 452. Blessed Pepin of Landen, mayor of the palace, 640. Saints German, abbot, and Randaut, martyrs, about 666. POPE JULIUS IIJulius de la Rovere, who ascended the papal throne in 1503, under the title of Julius II, is one of the most famous of all the Popes. He was the founder of the church of St. Peter at Rome: but his most remarkable acts were of a warlike character. During his papacy of ten years, he was continually engaged in war, first, against the Venetians, to recover the Romagna, in which affair he was assisted by the French and Germans: afterwards with the Germans against the French, in order to get these dangerous friends driven out of Italy. It was not till he had formed what he called 'a holy league,' in which he united to himself Spain, England, Venice, and the Swiss, that he succeeded in his object. In this war, he assumed all the characters and duties of a military commander, and few have exceeded him in spirit and resolution. As examples of the far-reaching policy of the man, he sent a splendid sword of state to the King of Scotland (James IV): it still exists among the Scottish regalia, exhibiting the armorial bearings of Pope Julius. In the great chest at Reikiavik cathedral in Iceland, are robes which he sent to the bishop of that remote island. Julius struck a medal to commemorate the great events of his reign; it represented him in pontificals, with the tiara on his head, and a whip in his hand, chasing the French, and trampling the shield of France under his feet. When Michael Angelo was making a statue of the pope, he said to him, 'Holy Father, shall I place a book in your hand?' 'No,' answered his Holiness, 'a sword rather-I know better how to handle it.' He was indeed much more of a soldier than an ecclesiastic, in any recognized sense of the term. He was the first pope who allowed his beard to grow, in order to inspire the greater respect among the faithful: a fashion in which he was followed by Charles V and other kings, and which spread through the courtiers to the people. THE CAMERONIANS-EPIGRAM BY BURNSIn the churchyard of the parish of Balmaghie, in the stewartry of Kirkcudbright, are the grave-stones of three persons who fell victims to the boot-and-saddle mission sent into Scotland under the last Stuarts. One of these rude monuments bears the following inscription: 'Here lyes David Halliday, portioner of Maifield, who was shot upon the 21st of February 1685, and David Halliday, once in Glengape, who was likewise shot upon the 11th of July 1685, for their adherence to the principles of Scotland's Covenanted Reformation. Beneath This Stone Two David Hallidays Do Lie, Whose Souls Now Sing Their Master's praise. To know If Curious Passengers desire, For What, By Whom, And Flow They Did Expire: They Did Oppose This Nation's Perjury, Nor Could 'they Join With Lordly Prelacy. Indulging Favours From Christ's Enemies Quenched Not Their Zeal. This Monument Then cries, These Were The Causes, Not To Be Forgot, Why They By Lag So Wickedly Were Shot: One Name, One Cause, One Grave, One Heaven, Do Tie Their Souls To That One God Eternally. The reverend gentleman who first printed this epitaph in his parochial contribution to the Statistical Account of Scotland (1794), made upon it the unlucky remark-'The author of which no doubt supposed himself to have been writing poetry'- unlucky when we consider the respect due to the earnestness of these men in a frame of religious opinion -which they thought right, and for which they had surrendered life. Burns, -who got the Statistical Account out of the subscription library of Dumfries, experienced the just feeling of the occasion, and rebuked the writer for his levity in a quatrain, which he inscribed on the margin, where it is still clearly to be traced: The Solemn League and Covenant Now brings a smile-now brings a tear- But sacred Freedom too was theirs: If thou'rt a slave, indulge thy sneer. It will perhaps he learned with some surprise that a remnant of those Cameronians who felt unsatisfied with the Presbyterian settlement at the Revolution, still exists in Scotland. Numbering about seven hundred persons, scattered chiefly throughout the south-west provinces of Scotland, they continue to decline taking the oath of allegiance to the reigning monarch, or to accept of any public office, holding that monarch and people have broken their pledge or covenant, by which they were bound in 1614 to extirpate popery, prelacy, and other errors. Holding out their testimony on this subject, they abstain from even exercising the elective franchise, alleging that to do so would be to sanction the aforesaid breach of covenant, to which they trace all the evils that befall the land. In May 1861, when this Reformed Presbytery met in Edinburgh, a trying question came before then: there were young men in their body who felt anxious to join in the volunteer movement: some had even done it. There were also some members who had exercised the elective franchise. To pursue a contemporary record: 'A lengthened discussion took place as to what should be done, and numerous reverend members urged the modification of the testimony, as regards the assumed identity of the representative and the voter, and as regards the interpretation of the oath of allegiance. Highly patriotic and almost loyal views were expressed on the Volunteer question, and warm expressions of admiration and love for Her Majesty were uttered, and of willingness to defend her person and protect the soil from invasion, so far as their service could be given apart from rendering fealty to the constitution. Another party in the Synod denounced the proposal to modify the testimony, as a backsliding and defection from the testimony. It was ultimately resolved, by 30 to 11, to appoint a committee to inquire into the soundness of the views contained in the testimony on the points mooted, and to relieve kirk sessions from the obligation to expel members who entertained doubts and difficulties on these matters, but meantime to recommend members of the Church to abstain from voting at elections. No similar recommendation having been made as to holding aloof from the Volunteer movement, it may be presumed that that point has been conceded.' THE FOLKLORE OF PLAYING CARDSThe long disputed questions respecting the period of the invention of playing-cards, and whether they were first used for purposes of divination or gambling, do not fall within the prescribed limits of this paper. Its object is simply to disclose-probably for the first time in print-the method or system of divination by playing-cards, constantly employed and implicitly depended upon, by many thousands of our fellow-countrymen and women at the present day. The smallest village in England contains at least one 'card-cutter,' a person who pretends to presage future events by studying the accidental combinations of a pack of cards. In London, the name of these fortune-tellers is legion, some of greater, some of lesser repute and pretensions: some willing to draw the curtains of destiny for a sixpence, others unapproachable except by a previously paid fee of from one to three guineas. And it must not be supposed that all of those persons are deliberate cheats: the majority of them 'believe in the cards' as firmly as the silly simpletons who employ and pay them. Moreover, besides those who make their livelihood by 'card-cutting,' there are numbers of others, who, possessing a smattering of the art, daily refer to the paste-board oracles, to learn their fate and guide their conduct. And when a ticklish point arises, one of those crones will consult another, and then, if the two cannot pierce the mysterious combination, they will call in a professed mistress of the art, to throw a gleam of light on the darkness of the future. In short, there are very few individuals among the lower classes in England who do not know something respecting the cards in their divinatory aspect, even if it be no more than to distinguish the lucky from the unlucky ones: and it is quite common to hear a person's complexion described as being of a heart, or club colour. For these reasons, the writer-for the first time as he believes-has applied the well-known term folklore to this system of divination by playing cards, so extensively known and so continually practised in the British dominions.  The Archduke of Austria Consulting a Fortune-Teller The art of cartomancy, or divination by playing-cards, dates from an early period of their obscure history. In the museum of Nantes there is a painting, said to be by Van Eyck, representing Philippe le Bon, Archduke of Austria, and subsequently King of Spain, consulting a fortune-teller by cards. This picture, of which a transcript is here given, cannot be of a later date than the fifteenth century. When the art was introduced into England is unknown: probably, however, the earliest printed notice of it in this country is the following curious story, extracted from Rowland's Judicial Astrology Condemned: 'Cuffe, an excellent Grecian, and secretary to the Earl of Essex, was told, twenty years before his death, that he should come to an untimely end, at which Cuffe laughed, and in a scornful manner intreated the soothsayer to shew him in what manner he should come to his end, who condescended to him, and calling for cards, intreated Cuffe to draw out of the pack any three which pleased him. He did so, and drew three knaves, and laid them on the table by the wizard's direction, who then told him, if he desired to see the sum of his bad fortune, to take up those cards. Cuffe, as he was prescribed, took up the first card, and looking on it, he saw the portraiture of himself cap-à-pie, having men encompassing him with bills and halberds. Then he took up the second, and there he saw the judge that sat upon him; and taking up the last card, he saw Tyburn, the place of his execution, and the hangman, at which he laughed heartily. But many years after, being condemned, he remembered and declared this prediction.' The earliest work on cartomancy was written or compiled by one Francesco Marcolini, and printed at Venice in 1540. There are many modern French, Italian, and German works on the subject: but, as far as the writer's knowledge extends, there is not an English one. The system of cartomancy, as laid down in those works, is very different from that used in England, both as regards the individual interpretations of the cards, and the general method of reading or deciphering their combinations. The English system, however, is used in all British settlements over the globe, and has no doubt been carried thither by soldiers' wives, who, as is well known to the initiated, have ever been considered peculiarly skilful practitioners of the art. Indeed, it is to a soldier's wife that this present exposition of the art is to be attributed. Many years ago the exigencies of a military life, and the ravages of a pestilential epidemic, caused the writer, then a puny but not very young child, to be left for many months in charge of a private soldier's wife, at an out-station in a distant land. The poor woman, though childless herself, proved worthy of the confidence that was placed in her. She was too ignorant to teach her charge to read, yet she taught him the only accomplishment she possessed,-the art of 'cutting cards,' as she termed it: the word cartomancy, in all probability, she had never heard. And though it has not fallen to the writer's lot to practice the art professionally, yet he has not forgotten it, as the following interpretations of the cards will testify. DIAMONDS

HEARTS

SPADES

CLUBS

The foregoing is merely the alphabet of the art: the letters, as it were, of the sentences formed by the various combinations of the cards. A general idea only can be given here of the manner in which those prophetic sentences are formed. The person who desires to explore the hidden mysteries of fate is represented, if a male by the king, if a female by the queen, of the suit which accords with his or her complexion. If a married woman consults the cards, the king of her own suit, or complexion, represents her husband: but with single women, the lover, either in esse or posse, is represented by his own colour: and all cards, when representing persons, lose their own normal significations. There are exceptions, however, to these general rules. A man, no matter what his complexion, if he wear uniform, even if he be the negro cymbal-player in a regimental band, can be represented by the king of diamonds:-note, the dress of policemen and volunteers is not considered as uniform. On the other hand, a widow, even if she be an albiness, can be represented only by the queen of spades. The ace of hearts always denoting the house of the person consulting the decrees of fate, some general rules are applicable to it. Thus the ace of clubs signifying a letter, its position, either before or after the ace of hearts, shows whether the letter is to be sent to or from the house. The ace of diamonds, when close to the ace of hearts, foretells a wedding in the house: but the ace of spades betokens sickness and death. The knaves represent the thoughts of their respective kings and queens, and consequently the thoughts of the persons whom those kings and queens represent, in accordance with their complexions. For instance, a young lady of a rather but not decidedly dark complexion, represented by the queen of clubs, when consulting the cards, may be shocked to find her fair lover (the king of diamonds) flirting with a wealthy widow (the queen of spades, attended by the ten of diamonds), but will be reassured by finding his thoughts (the knave of diamonds) in combination with a letter (ace of clubs), a wedding ring (ace of diamonds), and her house (the ace of' hearts): clearly signifying that, though he is actually flirting with the rich widow, he is, nevertheless, thinking of sending a letter, with an offer of marriage, to the young lady herself. And look, where are her own thoughts, represented by the knave of clubs: they are far away with the old lover, that dark man (king of spades) who, as is plainly shown by his being attended by the nine of diamonds, is prospering at the Australian diggings or elsewhere. Let us shuffle the cards once more, and see if the dark man, at the distant diggings, ever thinks of his old flame, the club-complexioned young lady in England. No! he does not. Here are his thoughts (the knave of spades) directed to this fair, but rather gay and coquettish woman (the queen of diamonds): they are separated but by a few hearts, one of them, the sixth (honourable courtship), shewing the excellent understanding that exists between them. Count, now, from the six of hearts to the ninth card from it, and lo! it is a wedding ring (the ace of diamonds): they will be married before the expiration of a twelvemonth. The general mode of manipulating the cards, when fortune-telling, is very simple. The person, who is desirous to know the future, after shuffling the cards ad libitum, cuts the pack into three parts. The seer, then, taking up these parts, lays the cards out, one by one, face upwards, upon the table, sometimes in a circular form, but oftener in rows consisting of nine cards in each row. Nine is the mystical number. Every nine consecutive cards form a separate combination, complete in itself: yet, like a word in a sentence, no more than a fractional part of the grand scroll of fate. Again, every card, something like the octaves in music, is en rapport with the ninth card from it: and these ninth cards form other complete combinations of nines, yet parts of the general whole. The nine of hearts is termed the 'wish-card.' After the general fortune has been told, a separate and different manipulation is performed, to learn if the pryer into futurity will obtain a particular wish; and, from the position of the wish-card in the pack, the required answer is deduced. In conclusion, a few words must be said on the professional fortune-tellers. That they are, genrally speaking, wilful impostors is perhaps true. Yet, paradoxical though it may appear, the writer feels bound to assert that those 'card-cutters ' whose practice lies among the lowest classes of society, really do a great deal of good. Few know what the lowest classes in our large towns suffer when assailed by mental affliction. They are, in most instances, utterly destitute of the consolations of religion, and incapable of sustained thought. Accustomed to live from hand to mouth, their whole existence is bound up in the present, and they have no idea of the healing effects of time. Their ill-regulated passions brook no self-denial, and a predominant clement of self rules their confused minds. They know of no future, they think no other human being ever suffered as they do. As they term it themselves, 'they are upset.' They perceive no resource, no other remedy than a leap from the nearest bridge, or a dose of arsenic from the first chemist's shop. Haply some friend or neighbour, one who has already suffered and been relieved, takes the wretched creature to a fortune-teller. The seeress at once perceives that her client is in distress, and, shrewdly guessing the cause, pretends that she sees it all in the cards. Having thus asserted her superior intelligence, she affords her sympathy and consolation, and points to hope and a happy future: blessed hope! though in the form of a greasy playing card. The sufferer, if not cured, is relieved. The lacerated wounds, if not healed, are at least dressed: and, in all probability, a suicide or a murder is prevented. Scenes of this character occur every day in the meaner parts of London. Unlike the witches of the olden time, the fortune-tellers are generally esteemed and respected in the districts in which they live and practise. And, besides that which has already been stated, it will not be difficult to discover sufficient reasons for this respect and esteem. The most ignorant and depraved have ever a lurking respect for morality and virtue; and the fortune-tellers are shrewd enough to know and act upon this feeling. They always take care to point out what they term 'the cards of caution,' and impressively warn their clients from falling into the dangers those cards foreshadow, but do not positively foretell, for the dangers may be avoided by prudence and circumspection. By referring to the preceding significations of the cards, it will be seen that there are cards of caution against dangers arising from drunkenness, covetousness, inconstancy, caprice, evil temper, illicit love, clandestine engagements, &c. Consequently the fortune-tellers are the moralists, as well as the consolers of the lower classes. They supply a want that society either cannot or will not do. If the great gulf which exists between rich and poor cannot be filled up, it would be well to try if, by any process of moral engineering, it could be bridged over. |