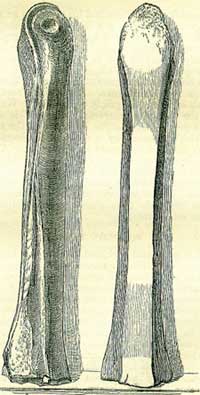

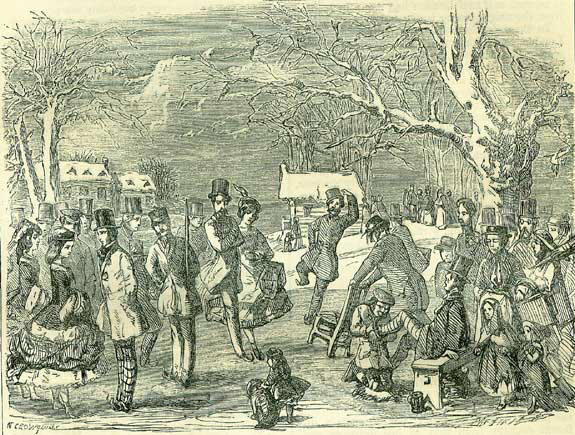

20th JanuaryBorn: Frederick, Prince of Wales, 1707, Hanover; Jean Jacques Barthelemy, 1716, Cassis. Died: Cardinal Bembo, 1547; Rodolph II, emperor, 1612; Charles, first Duke of Manchester, 1722; Charles VII, emperor, 1745; Sir James Fergusson, 1759; Lord Chancellor Yorke, 1770; David Garrick, 1779; John Howard, 1790. Feast Day: St. Fabian, pope, 250. St. Sebastian, 288. St. Euthymius, 473. St. Fechin, abbot in Ireland, 664: St. Fabian is a saint of the English calendar. ANNE OF AUSTRIAThis extraordinary woman, daughter of Philip II of Spain and queen of Louis XIII, exercised great influence upon the fortunes of France, at a critical period of its history; thus in part making good the witty saying,-that when queens reign, men govern; and that when kings govern, women eventually decide the course of events. Soon after the marriage of Anne, the administration fell into the hands of Cardinal Richelieu, who took advantage of the coldness and gravity of the queen's demeanour to inspire Louis with dislike and jealousy. Induced by him to believe that the queen was at the head of a conspiracy to get rid of him, Louis compelled her to answer the charge at the council table, when her dignity of character came to her aid; and she observed contemptuously, that 'too little was to be gained by the change to render such a design on her part probable.' Alienated from the king's affection and council, the queen remained without influence till death took away monarch and minister and left to Anne, as mother of the infant monarch (Louis XIV), the undisputed reins of power. With great discernment, she chose for her minister, Mazarin, who was entirely dependent upon her, and whose abilities she made use of without being in danger from his ambition. But the minister became unpopular: a successful insurrection ensued, and Anne and the court were detained for a time prisoners in the Palais Royal, by the mob. The Spanish pride of the queen was compelled to submit, and the people had their will. But a civil war soon commenced between Anne, her ministers and their adherents, on one side; and the noblesse, the citizens and people of Paris, on the other. The former triumphed, and hostilities were suspended; but the war again broke out: the court had secured a defender in Turenne, who triumphed over the young noblesse headed by the great Condé! The nobles and middle classes were never afterwards able to raise their heads, or offer resistance to the royal power up to the period of the great Revolution; so that Anne of Austria may be said to have founded absolute monarchy in France, and, not the subsequent imperiousness of Louis XIV. Anne's portrait in the Vienna gallery shows her to have been of pleasing exterior. Her Spanish haughtiness and love of ceremonial were impressed by education upon the mind of her son, Louis XIV', who bears the blame and the credit of much that was his mother's. She died at the age of sixty-four. DEATH OF GARRICKGarrick, who 'never had his equal as an actor, and will never have a rival,' at Christmas 1778, while on a visit to Lord Spencer, at Althorpe, had a severe fit, from which he only recovered sufficiently to enable him to return to town, where he expired on the 20th of January 1779, in his own house, in the centre of the Adelphi Terrace, in his sixty-third year. Dr. Johnson said: 'his death eclipsed the gaiety of nations.' Walpole, in the opposite extreme: 'Garrick is dead; not a public loss; for he had quitted the stage.' Garrick's remains lay in state at his house previous to their interment in Westminster Abbey, with great pomp: there were not at Lord Chatham's funeral half the noble coaches that attended Garrick's, which is attributable to a political cause. Burke was one of the mourners, and came expressly from Portsmouth to follow the great actor's remains. SIR JOHN SOANEThis successful architect died at his house in Lincoln's Inn Fields, surrounded by the collection of antiquities and artistic treasures which he bequeathed to the British nation, as 'the Soanean Museum.' He was a man of exquisite taste, but of most irritable temperament, and the tardy settlement of the above bequest to the country was to him a matter of much annoyance. His remains rest in the burial-ground of St. Giles's-in-the-Fields, St. Pancras, where two tall cypresses overshadow his tomb. At his death, the trustees appointed by parliament took charge of the Museum, library, books, prints, manuscripts, have cost £300. Garrick died in the back drawing-room, drawings, maps, models, plans and works of art. and the house and offices; providing for the admission of amateurs and students in painting, sculpture, and architecture; and general visitors. The entire collection cost Scone upwards of £50,000. THE FIRST PARLIAMENTIt was a great date for England, that of the First Parliament. There had been a Council of the great landholders, secular and ecclesiastic, from Anglo-Saxon times; and it is believed by some that the Commons were at least occasionally and to some extent represented in it. But it was during a civil war, which took place in the middle of the thirteenth century, marvelously like that which marked the middle of the seventeenth, being for law against arbitrary royal power, that the first parliaments, properly so called, were assembled. Matthew of Paris, in his Chronicle, first uses the word in reference to a council of the barons in 1246. At length, in December 1261, when that extraordinary man, Simon de Montfort Earl of Leicester-a mediaeval Cromwell-held the weak King Henry III in his power, and was really the head of the state, a parliament was summoned, in which there should be two knights for each county, and two citizens for every borough; the first clear acknowledgment of the Commons' clement in the state. This parliament met on the 20th of January 1265, in that magnificent hall at Westminster which still survives, so interesting a monument of many of the most memorable events of English history. The representatives of the Commons sat in the same place with their noble associates, probably at the bottom of the hall, little disposed to assert a controlling voice, not joining indeed in any vote, for we hear of no such thing at first, and far of course from having any adequate sense of the important results that were to flow from their appearing there that day. There, however, they were-an admitted Power, entitled to be consulted in all great national movements, and, above all, to have a say in the matter of taxation. The summer months saw Leicester overpowered, and himself and nearly all his associates slaughtered; many changes afterwards took place in the constitutional system of the country; but the Commons, once allowed to play a part in these great councils, were never again left out. Strange that other European states of high civilization and intelligence should be scarcely yet arrived at a principle of popular representation, which England, in comparative barbarism, realised for herself six centuries ago! THE COLDEST DAY IN THE CENTURY, JAN. 20, 1838Notwithstanding the dictum of M. Arago, that 'whatever may be the progress of the sciences, never will observers who are trustworthy and careful of their reputation, venture to foretell the state of the weather,'-this pretension received a singular support in the winter of 1838. This was the first year in which. the noted Mr. Murphy published his Weather Almanac; wherein his indication for the 20th day of January is 'Fair. Prob. lowest deg. of Winter temp.' By a happy chance for him, this proved to be a remarkably cold day. At sunrise, the thermometer stood at 4 below zero; at 9 a.m., +6; at 12 (noon), +14; at 2 p.m., 162; and then increased to 17, the highest in the day; the wind veering from the east to the south. The popular sensation of course reported that the lowest degree of temperature for the season appeared to have been reached. The supposition was proved by other signal circumstances, and particularly the effects seen in the vegetable kingdom. In all the nursery-grounds about London, the half-hardy, shrubby plants were more or less injured. Herbaceous plants alone seemed little affected, in consequence, perhaps, of the protection they received from the snowy covering of the ground. Two things may be here remarked, as being almost unprecedented in the annals of meteorology in this country: first, the thermometer below zero for some hours; and secondly, a rapid change of nearly fifty-six degrees. - Correspondent of the Philosophical Magazine, 1838. Still, there was nothing very remarkable in Murphy's indication, as the coldest day in the year is generally about this time (January 20). Nevertheless, it was a fortunate hit for the weather prophet, who is said to have cleared £3000 by that year's almanac! In Haydn's Dictionary of Dates it is recorded: 'Perhaps the coldest day ever known in London was December 25, 1796, when the thermometer was 16 below zero;' but contemporary authority for this statement is not given. SKATINGThis seems a fair opportunity of adverting to the winter amusement of skating, which is not only an animated and cheerful exercise, but susceptible of many demonstrations which may be called elegant. Holland, which with its extensive water surfaces affords such peculiar facilities for it, is usually looked to as the home and birthplace of skating; and we do not hear of it in England till the thirteenth century. In the former country, as has been remarked in an early page of this volume, the use of skates is in great favour; and it is even taken advantage of as a means of travelling, market-women having been known, for a prize, to go in this manner thirty miles in two hours. Opportunities for the exercise are, in Britain, more limited. Nevertheless, wherever a piece of smooth water exists, the due freezing of its surface never fails to bring forth hordes of enterprising youth to enjoy this truly inviting sport.  Skating has had its bone age before its iron one. Fitzstephen, in his History of London, tells us that it was customary in the twelfth century for the young men to fasten the leg-bones of animals under their feet by means of thongs, and slide along the ice, pushing themselves by means of an iron-shod pole. Imitating the chivalric fashion of the tournament, they would start in a career against each other, meet, use their poles for a push or a blow, when one or other was pretty sure to be hurled down, and to slide a long way in a prostrate condition, probably with some considerable hurt to his person, which we may hope was generally borne with good humour. In Moorfields and about Finsbury, specimens of these primitive skates have from time to time been exhumed, recalling the time when these were marshy fields, which in winter were resorted to by the youth of London for the amusements which Fitzstephen describes. A pair preserved in the British Museum is here delineated. The iron age of skating-whenever it might come-was an immense stride in advance. A pair of iron skates, made in the best modern fashion, fitted exactly to the length of the foot, and, well fastened on, must be admitted to be an instrument satisfactorily adapted for its purpose. With unskilled skaters, who constitute the great multitude, even that simple onward movement in which they indulge, using the inner edge of the skates, is something to be not lightly appreciated, seeing that few movements are more exhilarating. But this is but the walk of the art. What may be called the dance is a very different thing. The highly trained skater aims at performing a series of movements of a graceful kind, which may be looked upon with the same pleasure as we experience from seeing a fine picture. Throwing himself on the outer edge of his instrument, poising himself out of the perpendicular line in attitudes which set off a handsome person to uncommon advantage, he performs a series of curves within a certain limited space, cuts the figure 8,the figure 3, or the circle, worms and screws back-wards and forwards, or with a group of companions goes through what he calls waltzes and quadrilles. The calmness and serenity of these movements, the perfect self-possession evinced, the artistic grace of the whole exhibition, are sure to attract bystanders of taste, including examples of the fair, 'whose bright eyes Rain influence.'  Most such performers belong to skating clubs,-fraternities constituted for the cultivation of the art as an art, and to enforce proper regulations. In Edinburgh, there is one such society of old standing, whose favourite ground is Duddingston Loch, under the august shadow of Arthur's Seat. The writer recalls with pleasure skating exhibitions which he saw there in the hard winters early in the present century, when Henry Cockburn and the philanthropist James Simpson were conspicuous amongst the most accomplished of the club for their handsome figures and great skill in the art. The scene of that loch 'in full bearing,' on a clear winter day, with its busy stirring multitude of sliders, skaters, and curlers, the snowy hills around glistening in the sun, the ring of the ice, the shouts of the careering youth, the rattle of the curling stones and the shouts of the players, once seen and heard, could never be forgotten. In London, the amusements of the ice are chiefly practised upon the artificial pieces of water in the parks. On Sunday the 6th of January 1861, during' an uncommonly severe frost, it was calculated that of sliders and skaters, mostly of the humbler grades of the population, there were about 6000 in St. James's Park, 4000 on the Round Pond in Kensington Gardens, 25,000 in the Regent's Park, and 30,000 on the Serpentine in Hyde Park. There was, of course, the usual proportion of heavy falls, awkward collisions, and occasional immersions, but all borne good-humouredly, and none attended with fatal consequences. During the ensuing week the same pieces of ice were crowded, not only all the day, but by night also, torches being used to illuminate the scene, which was one of the greatest animation and gaiety. On three occasions there were refreshment tents on the ice, with gay flags, variegated lamps, and occasional fireworks; and it seemed as if half London had come to look on from the neighbouring walks and drives. In these ice-festivals, as usually presented in London, there is not much elegant skating to be seen. The attraction of the scene consists mainly in the infinite appearances of mirth and enjoyment which meet the gaze of the observer. The same frost period occasioned a very remarkable affair of skating in Lincolnshire. Three companies of one of the Rifle Volunteer regiments of that county assembled on the Witham, below the Stamp End Loch (December 29, 1860), and had what might be called a skating parade of several hours on the river, performing various evolutions and movements in an orderly manner, and on some occasions attaining a speed of fourteen miles an hour. In that province, pervaded as it is by waters, it was thought possible that, on some special occasion, a rendezvous of the local troops might be effected with unusual expedition in this novel way. ST. AGNES EVEThe feast of St. Agnes was formerly held as in a special degree a holiday for women. It was thought possible for a girl, on the eve of St. Agnes, to obtain, by divination, a knowledge of her future husband. She might take a row of pins, and plucking them out one after another, stick them in her sleeve, singing the whilst a paternoster; and thus insure that her dreams would that night present the person in question. Or, passing into a different country from that of her ordinary residence, and taking her right-leg stocking, she might knit the left garter round it, repeating: I knit this knot, this knot I knit, To know the thing I know not yet, That I may see The man that shall my husband be, Not in his best or worst array, But what he weareth every day; That I tomorrow may him ken From among all other men. They told her how, upon St. Agnes's Eve, Young virgins might have visions of delight, And soft adorings from their loves receive Upon the honey'd middle of the night, If ceremonies due they did aright; As, supperless to bed they must retire, And couch supine their beauties, lily white; Nor look behind, nor sideways, but require Of Heaven with upward eyes for all that they desire. Out went the taper as she hurried in; Its little smoke, in pallid moonshine, died: She closed the door, she panted, all akin To spirits of the air, and visions wide. No utter'd syllable, or, woe betide! But to her heart, her heart was voluble, 'Paining with eloquence her balmy side; As though a tongueless nightingale should swell Her throat in vain, and die, heart-stifled, in her dell. A casement high and triple arced there was, All garlanded with carver imag'rice Of fruits, and flowers, and bunches of knot grass, And diamended with panes of quaint device Innumerable of stains and splendid dyes, As are the tiger-moth's deep damask'd wings; And in the midst, 'mong thousand heraldries, And twilight saints, with dim emblazonings, A shielded 'scutcheon blush'd with blood of queens and kings. Full on this casement shone the wintry moon, And threw warm gules on Madeline's fair breast, As down she knelt for Heaven's grace and boon; Rose-bloom fell on her hands, together prest, And on her silver cross soft amethyst, And on her hair a glory, like a saint. Her vespers done, Of all its wreathed pearls her hair she frees; Unclasps her warmed jewels one by one; Loosens her fragrant bodice; by degrees Her rich attire creeps rustling to her knees: Half-hidden, like a mermaid in sea-weed, Pensive awhile she dreams awake, and sees, In fancy, fair St. Agnes in her bed, But dares not look behind, or all the charm is fled. Soon, trembling in her soft and chilly nest, In sort of wakeful swoon, perplex'd she lay; Until the poppied warmth of sleep oppress'd Her soothed limbs, and soul fatigued away; Flown, like a thought, until the morrow day, Blissfully haven'd both from joy and pain; Clasp'd like a missal where swart Paynims pray; Blinded alike from sunshine and from rain, As though a rose should shut, and be a bud again. Stol'n to this paradise, and so entranced, Porphyro gazed upon her empty dress, And listened to her breathing. He took her hollow lute,- Tumultuous,-and, in chords that tenderest be, He played an ancient ditty, long since mute, In Provence call'd 'La belle dame sans mercy:' Close to her ear touching the melody;- Wherewith disturb'd, she utter'd a soft moan: He ceased-she panted quick--and suddenly Her blue affrayed eyes wide open shone: Upon his knees he sank, pale as smooth-sculptured stone. Her eyes were open, but she still beheld, Now wide awake, the vision of her sleep: There was a painful change, that nigh expell'd The busses of her dream so pure and deep, At which fair Madeline began to weep, And moan forth witless words with many a sigh; While still her gaze on Porphyro would keep; Who knelt, with joined hands and piteous eye, Fearing to move or speak. she look'd so dreamingly. 'Ah, Porphyro!' said she, 'but even now Thy voice was at sweet tremble in mine ear, Made tuneable with every sweetest vow; And those sad eyes were spiritual and clear: How changed thou art! how pallid, chill, and drear! Give me that voice again, my Porphyro, Those looks immortal, those complainings dear! Oh, leave me not in this eternal woe, For if thou diest, my love, I know not where to go.' Beyond a mortal man impassion'd far At these voluptuous accents, he arose, Ethereal, flush'd, and like a throbbing star, Seen 'mid the sapphire heaven's deep repose, Into her dream he melted, as the rose Blendeth its odour with the violet, Solution sweet: meantime the frost-wind blows, Like Love's alarum pattering the sharp sleet Against the window-panes. Hark! 'tis an elfin-storm from faery land, Of haggard seeming, but a boon indeed. Arise-arise! the morning is at hand;- Let us away, my love, with happy speed. And they are gone: ay, ages long ago These lovers fled away into the storm. |