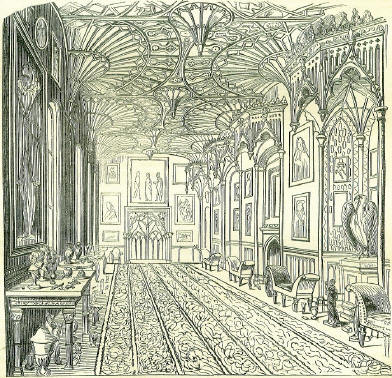

2nd MarchBorn: D. Junius Juvenal, Latin poet, A.D. circ. 40, Aquinnm; Sir Thomas Bodley (Bodleian Library), 1544, Exeter; William Murray, Earl of Mansfield, Lord Chief Justice, 1705, Perth; Sachet, Duke of Albuera, 1772, Lyons; Hugh Edward Strickland, naturalist, 1811, Righton, York. Died: Pope Pelagius I, 560; Lothaire III, of France, 986, poisoned, Compiegne; Robert Abbot, Bishop of Salisbury, 1618; Cardinal Bouillon, 1715, Rome; Francesco Bianchini, mathematician, 1729, Rome; Solomon Gessner, painter and poet, 1788, Zurich; John Wesley, founder of Methodism, 1791, London; Horace Walpole, Earl of Orford, 1797, Berkeley-square; Francis, fifth Duke of Bedford, 1802, Woburn Abbey; Francis II, Emperor of Austria, 1835; W. II. M. Olbers, astronomer, 1840; Giambattista Rubini, singer, 1854. Feast Day: St. Simplicius, Pope, buried 483. Martyrs under the Lombards, 6th century. St. Joavan, or Joevin, bishop in Armorica, 6th century. St. Marnan, of Scotland, 620. St Ceadda, or Chad, bishop of Lichfield, 673. St. Charles the Good, Earl of Flanders, martyr, 1124. ST. CEADDA, OR CHADSt. Chad is regarded as the missionary who introduced Christianity among the East Saxons. He was educated at the monastery of Lindisfarne, or Holy Island, of which. he became the bishop. He exercised at the same time the like jurisdiction over the extensive diocese of Mercia, first fixing that see at Lichfield, so called from the great number of martyrs slain and buried there, under Maximinanus Herudeus; the name signifying the field of carcases.' Bede assures us that St. Chad zealously devoted himself to all the laborious functions of his charge, visiting his diocese on foot, preaching the gospel, and seeking out the poorest and most abandoned persons in the meanest cottages and in the fields, that he might instruct them. When old age compelled him to retire, he settled with seven or eight monks near Lichfield. Tradition described him as greatly affected by storms; he called thunder 'the voice of God,' regarding it as designed to call men to repentance, and lower their self-sufficiency. On these occasions, he would go into the church, and continue in prayer until the storm had abated; it is related that seven days before his death, a monk named Arvinus, who was outside the building in which he lay, heard a sound as of heavenly music attendant upon a company of angels, who visited the saint to forewarn him of his end. Upon his canonization, St. Chad became the patron saint of medicinal springs. His bones were removed from Stow, where he died, to the site, of Lichfield cathedral, about the year. 700, and were enclosed in a rich shrine, which, being resorted to by multitudes of pilgrims, caused the gradual rise of the city of Lichfield from a small village. The whole place is rich with memorials of the good St. Chad; there is a small church dedicated to him, being erected on the site of St. Mary's church, which he built, and hard by which he was buried. It is related that the saint's tomb here had a hole in it, through which the pilgrims used to take out portions of the dust, which, mixed with holy water, they gave to men and animals to drink. The history of the cathedral has this romantic episode: in 1643, the Royalists, under the Earl of Chesterfield, fortified the close. They were attacked by the Parliamentary troops under Lord Brooke, of whom it is told that, on approaching the city, he prayed, if his cause was unjust, he might presently be cut off: whereupon he was killed by a brace of bullets from a musket, or wall piece, discharged by a deaf and dumb gentleman named Dyott, from the middle tower of the church, and fell at a spot now marked by an inscription: Twas levelled when fanatic Brooke The fair cathedral stormed and took; But thanks to heaven and good St. Chad, A guerdon meet the spoiler had! This occurring on the 2nd of March, the anniversary of St. Chad, was looked upon by the Royalists as a signal interference of Providence. On the cast side of the town is St. Chad's Well, which Leland describes as 'a spring of pure water, with a stone in the bottom of it, on which, some say, St. Chad was wont, naked, to stand in the water and pray; at this stone St. Chad had his oratory in the time of Wulfere, King of the Mercians.' Sir John Floyer, the celebrated physician, of Lichfield, who, in 1702, published a curious essay To Prove Cold Bathing both Safe and Useful, describes St. Chad as 'one of the first converters of our nation, who used immersion in the baptism of the Saxons. And the well near Stow, which may bear his name, was probably his baptistery, it being deep enough for immersion, and conveniently seated near the church; and that has the reputation of curing sore eyes, &c., as most holy wells in England do, which got that name from the baptizing the first Christians in them, and to the memory of the holy bishops who baptized in them they were commonly dedicated, and called by their name.' Sir John gives a table of diseases for which St. Chad's bath is efficacious, 'with some directions to the common people;' and he finds diseases for nearly every letter in the alphabet. A small temple like edifice has been erected over the well, in memory of St. Chad. Sir John Floyer, it should be added, set up a sort of rival bath, the water of which he shews to be the coldest in the neighbourhood, the success of which he foretells when he has 'prevailed over the prejudices of the common people, who usually despise all cheap and coalmen remedies, which have ordinarily the greatest effects.' In London we possessed a St. Chad's Well, on the east side of the Gray's Inn-road, near King's Cross, in Fifteen-foot lane. Here a tenement was, about a century ago, called St. Chad's Well-house, from the medicinal spring there, which was strongly recommended by the medical racially of the day. It long remained one of the favourite spas of the metropolis, with Bagnigge Wells, and the spring which gave name to Spa-fields. Two of these spas have almost gone out of recollection; but St. Chad's remained to our time, with its neat garden, and economical medicine at a half penny per glass. Old Joseph Mundell, the comedian, when he resided at Kentish Town, was for many years in the habit of visiting St. Child's three times a-week, and drinking its waters; as did the judge, Sir Allan Chanibre, when he lived at Prospect-house, Highgate. Mr. Alexander Mensall, who, for fifty years, kept the Gordon House Academy at Kentish Town, used to walk, with his pupils, once a week, to St. Chad's, to drink its waters, as a means of 'keeping the doctor out of the house.' In. 1825, Mr. Hone wrote: London is, however, still more extensively associated with St. Chad, through its excellent citizen Sir Hugh Myddelton; for the New River takes its rise from Chad's Well springs, situated in the meadows, about midway between Hertford and Ware; and when this water reached the north of London, it there gave name to Chadwell-street. SIR THOMAS BODLEYAmong the great men who adorn the reign of the virgin queen, not one of the least dignified figures is that of Sir Thomas Bodley, founder of the public library at Oxford. Bodley, in consequence of his father being unable to live in England during the reign of Mary, commenced his education at Geneva, and on returning home at fourteen was already a good scholar. Entering afterwards at Magdalen College, Oxford, he became in succession a fellow of Merton, and the orator of the University. At a mature age, he travelled on the Continent, chiefly that he might acquire the modern languages; then, returning to his college, he devoted himself to the study of history and politics. In 1583, he was made gentleman usher to Queen Elizabeth; and in 1585 he married a rich widow of Bristol. From soon after this date until 1597, Bodley was employed by Queen Elizabeth in several embassies and commissions, and he resided nearly five years in Holland. It need scarcely be remarked how largely this continental education, travel, and experience must have qualified Bodley for the noble task which he had set himself-the restoration of the public library of the University of Oxford. Bodley, having succeeded in all his negotiations for his royal mistress, obtained his final recall in 1597, when, finding his advancement at court obstructed by the jealousies and intrigues of great men, he retired from it, and all public business. In the same year he set about founding anew the public. library, by offering to restore the buildings in which had been deposited the books and manuscripts left by Humphrey, the good Duke of Gloucester, all of which had been destroyed or dispersed before the year 1555, the room continuing empty until restored by Sir Thomas Bodley. His offer being gladly accepted, he settled a fund for the purchase of books, and the maintenance of proper officers, and commenced his undertaking by presenting a large collection of books purchased on the Continent, and valued at £10,000. Other collections and contributions followed, to such an amount that the old building was no longer sufficient to contain them, when Sir Thomas Bodley proposed to enlarge the edifice; and, his liberal example being followed, the University was enabled to add three other sides, forming the quadrangle and rooms for the schools, &c. He did not, however, live to see the whole completed. This illustrious person died in 1612. The Bodleian Library was first opened to the public on the 8th of November 1602. Sir Thomas, then lately knighted, was declared the founder; and in 1605, Lord Buckhurst, Earl of Dorset, and Chancellor of the University, placed his bust in the library. An annual speech in praise of Sir Thomas Bodley was founded in 1681, and is delivered on the visitation-day of the library, November the 8th. Casaubon visited the Bodleian Library very shortly after the completion of the first building, in 1606: 'None of the colleges,' he writes, attracted me so much as the Bodleian Library, a work rather for a king than a private man. It is certain that Bodley, living or dead, must have expended 200,000 livres on that building. The ground-plot is the figure of the letter T. The part which represents the perpendicular stem was formerly built by some prince, and is very handsome; the rest was added by Bodley with no less magnificence. The upper story is the library itself, very well built, and fitted with an immense quantity of books. Do not imagine that such plenty of manuscripts can be found here as in the Royal Library (of Paris); there are not a few manuscripts in England, but nothing to what the King possesses. But the number of books is wonderful, and increasing every year; for Bodley has bequeathed a considerable revenue for that purpose. As long as I remained at Oxford I passed whole days in the Library; for books cannot be taken out, but the library is open to all scholars for seven or eight hours every day. You might always see, therefore, many of these greedily enjoying the banquet prepared for them, which gave me no small pleasure.' As you enter the library you are struck by an excellent portrait of the founder, by Cornelius Jansen; and by its side and opposite, those of the first principal librarians. There are also other portraits of much interest, particularly that of Junius, the famous Teutonic scholar, by Vandyck; of Selden, an exquisite painting by Mytens; and of Humphrey Wanley, some time under-librarian here. The ceiling is painted with the arms of the University, and those of Bodley. The books in this part of the library retain still their ancient classified arrangement, according to Bodley's will. It would require a volume to enumerate the many important additions in books and manuscripts, made to this library by its numerous benefactors. The famous library of more than 200 Greek manuscripts, formed by Giacomo Baroccio, a Venetian nobleman, was added in 1627, by will of Herbert, Earl of Pembroke, then Chancellor of the University. In 1633, nearly the same number of manuscripts, chiefly Latin and English, were given by Sir Kenelm Digby. Both these collections are supposed to have been presented at the instigation of Archbishop Laud, who succeeded the Earl as Chancellor, and who himself enriched the library with more than 1300 manuscripts in the Oriental and European tongues. The Selden Library, of more than 8000 volumes of printed books and manuscripts, was next deposited here by Selden's executors. In the two succeeding centuries we find among the benefactors Junius, Marshall, Hyde, Lord Crewe, Tanner, Bishop of St. Asaph, Rawlinson, Browne Willis, Thomas Hearne, and Godwin. Among the subsequent additions were the collections of early plays and English poetry, by Malone; and of topography by Gough. To these, prompted by a similar feeling of princely munificence, the late Mr. Francis Douce added his tastefully collected library of printed books and manuscripts, coins and medals, prints and drawings, the result of years of patient and untiring research. The funds of the library are kept up by small fees paid by members of the University at their matriculation, and by a trifling annual contribution from all as soon as they shall have taken their B.A. degree. This, with legacies bequeathed to it, independent of the University chest, has enabled the library, from time to time, to increase its treasures. The collections of manuscripts of D'Orville; Clarke, the celebrated traveller; the Abbate Canonici of Venice; the printed books and manuscripts of the Oppenheimer family, comprising the finest library of Rabbinical literature ever got together, have, by these means, been purchased. A large addition of books is also made annually by new publications sent to the library, under the Act of Parliament for securing copyright. HORACE WALPOLEA person to whom the second stratum of modern history is so much indebted as Horace Walpole, could not well be overlooked in the present work. Born just within the verge of aristocratic rank-third son of the great minister Sir Robert Walpole, who was ennobled as Earl of Orford-and living through a century of unimportant events and little men-the subject of this notice devoted talents of no mean order to comparatively trifling pursuits, and yet with the effect of conferring an obligation on the world. His works on royal and noble authors and on artists are valuable books; his letters, in which he has chronicled all the curious and memorable affairs, both public and private, during sixty years, are of inestimable value as a general picture of the time, though perhaps we are disposed to rest too securely on them for details of fact. It is vain to hanker on the essential effeminacy and frivolity of Horace Walpole, or even to express our fears that he did not possess much heart. Take him for what he is, and what he did for us, and does any one not feel that we could well have spared a better man?  Horace had twenty-eight years of parliamentary life, without acquiring any distinction as a politician. He professed strenuous Whig opinions, but in his heart was without popular sympathies. His historical works shew that he was capable of considerable literary efforts. Being, however, a well-endowed sinecurist, and a member of the highest aristocratic circles, he had no motive for any great exertion of his faculties. It literally became the leading business of this extraordinary man to make up a house of curiosities. His great 'work' was Strawberry Hill. He had purchased this little mansion as a more cottage in 1747, and for the remaining fifty years of his life he was constantly adding to it, decorating it, and increasing the number of the pictures, old china, and other objects of virtue which he had assembled in it. The pride of his life-old bachelor as he was-was to see pretty duchesses and countesses wandering through its corridors and basking on its little terrace. There is one redeeming trait in the fantastic aristocrat. When he succeeded in old age to the family titles, he could hardly be induced to act the peer's part, and still signed with his ordinary name, or as 'Uncle of the late Earl of Orford.' The love of books and articles of taste was at least sufficient to over-power in his mind the glitter of the star. The glories of Strawberry Hill came to an end in 1842, when the whole of the pictures and curiosities which it contained were dispersed by a twenty-four days' sale, through the agency of the renowned auctioneer, George Robins. On that occasion, a vast multitude of people flocked to the house to see it, and for the chance of picking up some of its multifarious contents. The general style of the mansion was too unsubstantial and trashy to give much satisfaction. Yet it was found to contain a Great Staircase, highly decorated, an Armory, a room called the Star-chamber, a Gallery, and some other apartments. All were as full as they could hold of pictures, armour, articles of bijouterie, china, and other curiosities. One room was devoted to portraits by Holbein. In another was the hat of Cardinal Wolsey, together with a clock which had been presented by King Henry VIII as a morning gift to Anne Bullen. The dagger of King Henry VIII and a mourning ring for Charles I, vied with the armour of Francis I in attracting attention. One article of great elegance was a silver bell, which had been formed by Bonvenuto Cellini, for Pope Clement VI, with a rich display of carvings on the exterior, representing serpents, flies, grasshoppers, and other insects, the purpose of the bell having been to serve in a papal cursing of these animals, when they on one occasion became so trouble-some as to demand that mode of castigation. Another curious article, suggestive of the beliefs of a past age, was the shew-stone of Dr. Dec, a piece of polished cannel coal, which had been used by that celebrated mystic as a mirror in which to see spirits. The general style of Strawberry Hill was what passed in Walpole's days as Gothic. However really deficient it might be in correctness, or inferior in taste, the effect of the interior of the Great Gallery was interesting. Conspicuous in this room was a portrait of Lady Falkland in white by Van Somer, which suggested to Walpole the incident of the figure walking out of its picture frame in his tale of the Castle of Otranto. Strawberry Hill, if in its nature capable of being preserved, would have been the best memorial of Horace Walpole. This failing, we find his next best monument in the collective edition of his letters, as arranged and illustrated by Mr. Peter Cunningham. Allowing for the distortions of whim and caprice, and perhaps some perversions of truth through prejudice and spleen, this work is an inestimable record of the era it represents. Its prominent characteristic is garrulity. In the language of the Edinburgh Review (Dec. 1818): Walpole was, indeed, a garrulous old man nearly all his days; and, luckily for his gossiping propensities, he was on familiar terms with the gay world, and set down as a man of genius by the Princess Amelia, George Selwyn, Mr. Chute, and all persons of the like talents and importance. His descriptions of court dresses, court revels, and court beauties, are in the highest style of perfection,-sprightly, fantastic, and elegant: and the zeal with which he hunts after an old portrait or a piece of broken glass, is ten times more entertaining than if it were lavished on a worthier object. He is indeed the very prince of gossips,-and it is impossible to question his supremacy, when he floats us along in a stream of bright talk, or shoots with us the rapids of polite conversation. He delights in the small squabbles of great politicians and the puns of George Selwyn,-enjoys to madness the strife of life with half a dozen bitter old women of quality,-revels in a world of chests, cabinets, commodes, tables, boxes, turrets, stands, old printing, and old china,-and indeed lets us loose at once amongst all the frippery and folly of the last two centuries with. an ease and a courtesy equally amazing and delightful. His mind, as well as his house, was piled up with Dresden china, and illuminated through painted glass; and we look upon his heart to have been little better than a case full of enamels, painted eggs, ambers, lapis-lazuli, cameos, vases, and rock crystals. This may in some degree account for his odd and quaint manner of thinking, and his utter poverty of feeling. He could not get a plain thought out of that cabinet of curiosities, his mind;-and he had no room for feeling,-no place to plant it in, or leisure to cultivate it. He was at all times the slave of elegant trifles; and could no more screw himself up into a decided and solid personage, than he could divest himself of petty jealousies and miniature animosities. In one word, everything about him was in little; and the smaller the object, and the less its importance, the higher did his estimation and his praises of it ascend. He piled up trifles to a colossal height-and made a pyramid of nothings 'most marvellous to see.' THE FIFTH DUKE OF BEDFORD AND BLOOMSBURY HOUSEOn the 2nd of March 1802, died Francis, fifth Duke of Bedford, unmarried, at the age of thirty-seven, deeply lamented on account of his amiable character and the enlightened liberality with which he had dispensed the princely fortunes of his family. In his tenure of the honours and estates of the house of Bedford, we find but one incident with which we are disposed to find fault, or at which we might express regret, the taking down of that family mansion in Bloomsbury-square which had been the residence of the patriot lord, and toward which he had thrown a look of sorrow on passing to the scaffold in Lincoln's Inn Fields. That house should have been kept up by the race of Russell as long as two bricks of it would hold together. This mansion, which was taken down in 1800, had been built in the reign of Charles II for Thomas Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton, and it came into the Bedford family by the marriage of the patriot Lord Russell to the admirable daughter of the Earl, Lady Rachel. It occupied the whole north side of the square, with gardens extending behind towards what is now the City-road, the site of Russell-square, and of many handsome streets besides. There was something not easily to be accounted for in the manner in which the house and its contents were disposed of. The whole were set up to auction (May 7, 1800). A casual dropper-in bought the whole of the furniture and pictures, including Thorn-hill's copies of the cartoons (now in the Royal Academy), for the sum of £6,000. In Dodsley's Annual Register, 1800, the gallery is described as the only room of consequence in the mansion. This was fitted up by the fourth Duke of Bedford, who placed in it the copies of the cartoons by Thornhill, at the sale of whose collection they had been bought by the Duke for £200. The prices fetched by some of the pictures at the Bloomsbury House sale, by Mr. Christie, appear very small: as, St. John preaching in the Wilderness, by Raphael, 95 guineas; an Italian Villa, by Gainsborough, 90 guineas; four paintings of a Battle, by Cassinovi, which cost the Duke £1,000, were sold for 60 guineas; a fine Landscape, by Cuyp, 200 guineas; two beautiful bronze figures, Venus and Antinous, 20 guineas, and Venus couchant, from the antique, 20 guineas. Among the pictures was the Duel between Lord Mohun and the Duke of Hamilton, in Hyde Park. The celebrated statue of Apollo, which stood in the hall of Bedford House, was removed to Woburn: it originally cost 1000 guineas. The week after, there were sold the double rows of lime-trees in the garden, and the ancient stem of the light and graceful acacia which stood in the court before the house, and which Walpole commends in his Essay on Landscape Gardening. The house was immediately pulled down; and, says the Annual Register, 'the site of a new square, of nearly the same dimensions as Lincoln's Inn Fields, and to be called Russell-square, has been laid out.' The Bedford property in Bloomsbury has realized enormous sums: for example, New Oxford-street, occupying the site of the Rookery of St. Giles, was made at a cost of £290,227 4s. 10d., of which £113,963 was paid to the Duke of Bed-ford alone, for freehold purchases. HORACE WALPOLE ON BALLOONSOn March. 2, 1784, Blanchard, the aeronaut, made his first ascent from Paris, in a hydrogen balloon, to which he added wings and a rudder, proved on trial to be useless. This was a busy year in ballooning; and among those who took interest in the novelty was Horace Walpole, who, in a letter of Jan. 13, thus speculates upon the chances of turning aerostation to account: 'You see the Argonauts have passed the Rubicon. By their own account they were exactly birds; they flew through the air; perched on the top of a tree, some passengers climbed up, and took them in their nest. The smugglers, I suppose, will be the first that will improve upon the plan. However, if the project be ever brought to perfection, (though I apprehend it will be addled, like the ship that was to live under water and never came up again,) it will have a different fate from other discoveries, whose inventors are not known. In this age all that is done (as well as what is never done) is so faithfully recorded, that every improvement will be registered chronologically. Mr. Blanchard's Trip to Calais puts me in mind of Dryden's Indian Emperor: What divine monsters, 0 ye gods, are these, That float in air, and fly upon the seas? Dryden little thought that he was prophetically describing something more exactly than ships as conceived by Mexicans. If there is no air-sickness, and I were to go to Paris again, I would prefer a balloon to the packet-boat, and had as lief roost in an oak as sleep in a French. inn, though I were to caw for my breakfast like the young ravens.' In the autumn of the same year, Walpole is writing a letter at Strawberry Hill, when his servants call him away to sec a balloon; he supposes Blanchard's, that was to be let off at Chelsea in the morning. He is writing to a friend, Mr. Conway, and thus continues: 'I saw the balloon from the common field before the window of my round tower. It appeared about a third of the size of the moon, or less, when setting, something above the tops of the trees on the level horizon. It was then descending; and after rising and declining a little, it sunk slowly behind the trees, I should think about or beyond Sunbury, at five minutes after one.' This ascent leads Walpole to say, 't'other night I diverted my-self with a sort of meditation on future airgonation, supposing it will not only be perfected, but will depose navigation. I did not finish it, because I am not skilled, like the gentleman that used to write political ship-news, in that style which I wanted to perfect my essay; but in the prelude I observed how ignorant the ancients were in sup-posing Icarus melted the wax of his wings by too near access to the sun, whereas he would have been frozen to death before he made the first port on that road. Next I discovered an alliance between Bishop Wilkins's art of flying and his plan of universal language; the latter of which he, no doubt, calculated to prevent the want of an interpreter when he should arrive at the moon. 'But I chiefly amused myself with ideas of the change that would be made in the world by the substitution of balloons for ships. I supposed our seaports to become deserted villages; and Salisbury Plain, Newmarket Heath, (another canvass for alteration of ideas,) and all downs (but the Downs), arising into dockyards for aerial vessels. Such a field would be ample in furnishing new speculations. But to come to my shipnews: 'The good balloon, Daedalus, Captain Wingate, will fly in a few days for China; he will stop at the Monument to take in passengers. 'Arrived on Brandsands, the Vulture, Captain Nabob; the Tortoise snow, from Lapland; the Pet-en-l'air, from Versailles; the Dreadnought, from Mount Etna, Sir W. Hamilton commander; the Tympany, Montgolfler. Foundered in a hurricane, the Bird of Paradise, from Mount Ararat; the Bubble, Sheldon, took fire, and was burnt to her gallery; and the Phoenix is to be cut down to a second-rate. 'In these days Old Sarum will again be a town, and have houses in it. There will be fights in the air with wind-guns, and bows and arrows; and there will be prodigious increase of land for tillage, especially in France, by breaking up all public roads as useless.' In December he writes: This enormous capital (London), that must have some occupation, is most innocently amused with those philosophic playthings, air-balloons. But, as half-a-million of people that impassion themselves for any object are always more childish than children, the good souls of London are much fonder of the airgonauts than of the toys themselves. Lunardi, the Neapolitan secretary, is said to have bought three or four thousand pounds in the stocks, by exhibiting his person, his balloon, and his dog and cat, at the' Pantheon, for a shilling each visitor. Blanchard, a Frenchman, is his rival, and I expect that they will soon have an air-fight in the clouds, like a stork and a kite.' Since Walpole's time there have been changes in the value of public roads and the serviceableness of sea-ports, but from causes apart from aerial navigation,-in which art literally no progress has been made since the year 1784. ESCAPE OF LOUIS PHILIPPE TO ENGLAND, 1848It was on the 2nd of March 1848, that Louis Philippe, King of the French, after a career of vicissitude, perhaps unexampled in modern times, finally left France, and sought a sheltering place in England. The particulars of the King's escape form an episode of 'singular interest in the life of the dethroned monarch, and are related in the Quarterly Review for March 1850, being further confirmed to the Editor of the Book of DAYS by one of the principal agents engaged in the transaction. 'Every one who has sailed in front of Honfleur, must have remarked a little chapel situated on the, top of the wooded, hill that overhangs the town it was dedicated by the peity of the sailors of ancient days to Notre Dames de Grace, as was a similar one on the Opposite shore. From it, Mr. de Perthuis' cottage is commonly called La Grace; and we can easily imagine the satisfaction of the Royal guests at finding themselves under the shelter of a friendly roof with a name of such good omen. 'On Thursday, the 2nd of March (1848), just at daybreak, the inmates of La Grace were startled by the arrival of a stranger, who, however, turned out to be Mr. Jones, the English Vice-Consul at Havre, with a message from the Consul, Mr. Featherstonhaugh, announcing that the Express steam-packet had returned, and was placed entirely at the King's disposal, and that Mr. Jones would concert with his Majesty the means of embarkation. He also brought news, if possible, more welcome-a letter from Mr. Beason, announcing that the Duke de Nemours, his little daughter, the Princess Marguerite, and the Princess Clementine, with her husband and children, were safe in England. This double good news reanimated the whole party, who were just before very much exhausted both in body and mind. But the main difficulty still remained; how they were to get to the Express? 'Escape became urgent; for not only had the Procureur de la Republique of the district hastened to Trouville with his gendarmes to seize the stranger (who, luckily, had left it some hours), but, having ascertained that the stranger was the King, and that Mr. de Perthuis was in his company, that functionary concluded that his Majesty was at La Grace, and a domiciliary visit to the Pavilion was subsequently made. 'The evening packet (from Havre to Honfleur) brought back Mr. Besson and Mr. Jones, with the result of the council held on the other side of the water, which was, that the whole party should instantly quit La Grace, and, taking advantage of the dusk of the evening, embark in the same packet by which these gentlemen had arrived, for a passage to Havre, where there were but a few steps to be walked between leaving the Honfleur boat and getting on board the Express. The Queen was still to be Madame Lebrun; but the King, with an English passport, had become Mr. William Smith. Not a moment was to be lost. The King, disguised as before, with the addition of a coarse great-coat, passed, with MM. de Rumigny and Thuret, through one line of streets; Madame Le Brun, leaning on her nephew's arm, by another. There was a great crowd on the quay of Honfleur, and several gendarmes; but Mr. Smith soon recognised Mr. Jones, the Vice-Consul, and, after a pretty loud salutation in English (which few Mr. Smiths speak better), took his arm, and stepped on board the packet, where he sat down immediately on board one of the passengers' benches. Madame Le Brun took a seat on the other side. The vessel, the Courier, happened to be one that the King had employed the summer before at Tréport. M. Lamartine, who mistakes even the place, and all the circumstances of this embarkation, embroiders it with a statement that the King was recognised by the crew, who, with the honour and generosity inherent in all Frenchmen, would not betray him. We are satisfied that there are very few seamen who would have betrayed him; but the fact is, that he was not recognised; and, when the steward went about to collect the fares and some gratuity for the band, Mr. Smith shook his head, as if understanding no French, and his friend Mr. Jones paid for both. On landing at the quay of Havre, amidst a crowd of people and the criers of the several hotels was Mr. Featherstonhaugh, who, addressing Mr. Smith as his uncle, whom he was delighted to see, conducted him a few paces further on, into the Express, lying at the quay, with her steam up; Madame Le Brun following.' |