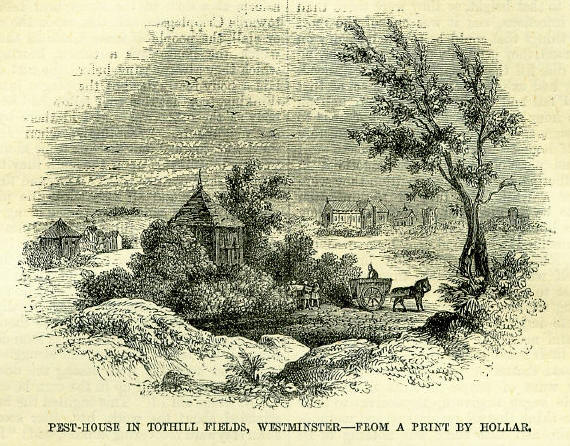

19th SeptemberBorn: Henry III of France, 1551, Fontainebleau; Robert Sanderson, bishop of Lincoln, and high-church writer, 1587, Rotherham, Yorkshire; Rev. William Kirby, entomologist, 1759, Witnesham Hall, Suffolk; Henry, Lord Brougham and Vaux, 1779, Edinburgh. Died: Charles Edward Poulett Thomson, Lord Sydenham, governor of Canada, 1841; Professor John P. Nichol, author of The Architecture of the Heavens, &c., 1859, Rothesay. Feast Day: St. Januarius, bishop of Benevento, and his companions, martyrs, 305. Saints Peleus, Pa-Termuthes, and companions, martyrs, beginning of 4th century. St. Eustochius, bishop of Tours, 461. St. Sequanus or Seine, abbot, about 580. St. Theodore, archbishop of Canterbury, confessor, 690. St. Lucy, virgin, 1090. THE BATTLE OF POITIERSOn 19th September 1356, the second great battle fought by the English on French soil, in assertion of their chimerical claim to the crown of that country, was won by the Black Prince, in the face, as at Crécy, of an overwhelming superiority of numbers. Whilst the army of the French king mustered sixty thousand horse alone, besides foot soldiers, the whole force of Edward, horse and foot together, did not exceed ten thousand men. The engagement was not of his own seeking, but forced upon him, in consequence of his having come unexpectedly on the rear of the French army in the neighbourhood of Poitiers, to which town he had advanced in the course of a devastating expedition from Guienne, without being aware of the proximity of the French monarch. Finding that the whole of the surrounding country swarmed with the enemy, and that his retreat was effectually cut off, his first feeling seems to have been one of consternation. 'God help us!' he exclaimed; and then added undauntedly: We must consider how we can best fight them. A strong position amid hedges and vineyards was taken up by him, and as night was then approaching, the English troops prepared themselves for repose in expectation of tomorrow's battle. In the morning, King John marshalled his forces for the combat, but just as the engagement was about to commence, Cardinal Talleyrand, the pope's legate, arrived at the French camp, and obtained a reluctant permission to employ his offices, as mediator, to prevent bloodshed. The whole of that day (Sunday) was spent by him in trotting between the two armies, but to no effect. The English leader made the very liberal offer to John, to restore all the towns and castles which he had taken in the course of his campaign, to give up, unransomed, all his prisoners, and to bind himself by oath to refrain for seven years from bearing arms against the king of France. But the latter, confiding in his superiority of numbers, insisted on the Black Prince and a hundred of his best knights surrendering themselves prisoners, a proposition which Edward and his army indignantly rejected. Next morning at early dawn, the trumpets sounded for battle, and even then the indefatigable cardinal made another attempt to stay hostilities; but on riding over to the French camp for that purpose, he was cavalierly told to go back to where he came from, with the significant addition, that he had better bring no more treaties or pacifications, or it would be the worse for himself. Thus repulsed, the worthy prelate made his way to the English army, and told the Black Prince that he must do his best, as he had found it impossible to move the French king from his resolution. 'Then God defend the right!' replied Edward, and prepared at once for action. The attack was commenced by the French, a body of whose cavalry came charging down a narrow lane with the view of dislodging the English from their position; but they encountered such a galling fire from the archers posted behind the hedges, that they turned and fled in dismay. It was now Edward's turn to assail, and six hundred of his bowmen suddenly appeared on the flank and rear of John's second division, which was thrown into irretrievable confusion by the discharge of arrows. The English knights, with the prince at their head, next charged across the open plain upon the main body of the French army. A division of cavalry, under the Constable of France, for a time stood firm, but ere long was broken and dispersed, their leader and most of his knights being slain. A body of reserve, under the Duke of Orleans, fled shamefully without striking a blow. King John did his best to turn the fortune of the day, and, accompanied by his youngest son, Philip, a boy of sixteen, who fought by his side, he led up on foot a division of troops to the encounter. After having received two wounds in the face, and been thrown to the ground, he rose, and for a time defended himself manfully with his battle-axe against the crowd of assailants by whom he was surrounded. The brave monarch would certainly have been slain had not a French knight, named Sir Denis, who had been banished for killing a man in a fray, and in consequence joined the English service, burst through the press of combat-ants, and exclaimed to John in French: 'Sire, surrender.' The king, who now felt that his position was desperate, replied: 'To whom shall I surrender? Where is my cousin, the Prince of Wales?' 'He is not here,' answered Sir Denis; 'but surrender to me, and I will conduct you to him.' 'But who are you?' rejoined the king. 'Denis de Morbecque,' was the reply; 'a knight of Artois; but I serve the king of England because I cannot belong to France, having forfeited all I had there.' 'I surrender to you,' said John, extending his right-hand glove; but this submission was almost too late to save his life, for the English were disputing with Sir Denis and the Gascons the honour of his capture, and the French king was in the utmost danger from their violence. At last, Earl Warwick and Lord Cobham came up, and with every demonstration of respect conducted John and his son Philip to the Black Prince, who received them with the utmost courtesy. He invited them to supper, waited himself at table on John, as his superior in age and rank, praised his valour and endeavoured by every means in his power to diminish the humiliation of the royal captive. The day after the victory of Poitiers, the Black Prince set out on his march to Bordeaux, which he reached without meeting any resistance. He remained during the ensuing winter in that city; concluded a truce with the Dauphin, Charles, John's eldest son; and, in the spring of 1357, crossed over to England with the king and Prince Philip as the trophies of his prowess. A magnificent entrance was made into London, John being mounted on a cream-coloured charger, whilst the Prince of Wales rode by his side on a little black palfrey as his page. Doubtless the French king would have willingly dispensed with this ostentatious mode of respect. He was lodged as a prisoner in the Savoy Palace, and continued there till 1360, when, in consequence of the treaty of Bretigny, he was enabled to return to France. The stipulations of this compact having been broken by John's sons and nobles, he conceived himself bound in honour to surrender himself again a prisoner to England, and actually returned thither, when Edward III received him with great affection, and assigned him again his old quarters in the Savoy. His motives in displaying so nice a sense of honour, a proceeding so unusual in those times, when oaths and treaties seemed made only to be broken, have been variously construed. In charity, however, and as affording a pleasing exception to the general maxims of the age, we may, in default of any positive evidence to the contrary, assume that John was really actuated by what most persons deemed then a gratuitous and romantic scruple. He did not long survive his second transference to the Savoy, and died there in April 1364. THE GREAT PLAGUE OF LONDONThe week ending the 19th of September 1665, was that in which this memorable calamity reached its greatest destructiveness. It was on the 26th of the previous April that the first official notice announcing that the plague had established itself in the parish of St. Giles-in-the-Fields, appeared in the form of an order of council, directing the pre-cautions to be taken to arrest its progress. The evil had at this time been gradually gaining head during several weeks. Vague suspicions of danger had existed during the latter part of the previous year, and serious alarm was felt, which however gradually abated. But the suspicions proved to be too true; the infection, believed to have been brought over from Holland, had established itself in the parish of St. Giles, remained concealed during the winter, and began to shew itself in that and the adjoining parishes at the approach of spring, by the increase in their usual bills of mortality. At the date of the order of council just alluded to, there could be no longer any doubt that the parishes of St. Giles, St. Andrews, Holborn, and one or two others adjoining, were infected by the plague. During the months of May and June, the infection spread in spite of all the precautions to arrest its progress, but, towards the end of the latter month, the general alarm was increased by the certainty that it had not only spread into the other parishes outside the walls, but that several fatal cases had occurred in the city. People now began to hurry out of town in great numbers, while it was yet easy to escape, for as soon as the infection had become general, the strictest measures were enforced to prevent any of the inhabitants leaving London, lest they might communicate the dreadful pestilence to the towns and villages in the country. One of the most interesting episodes in the thrilling narrative of Defoe is the story of the adventures of three men of Wapping, and the difficulties they encountered in seeking a place of refuge in the country to the north-east of London, during the period while the plague was at its height in the metropolis. The alarm in London was increased when, in July, the king with the court also fled, and took refuge in Salisbury, leaving the care of the capital to the Duke of Albemarle. The circumstance of the summer being unusually hot and calm, nourished and increased the disease. An extract or two from Defoe's narrative will give the best notion of the internal state of London at this melancholy period. Speaking of the month in which the court departed for Salisbury, he tells us that already: the face of London was strangely altered-I mean the whole mass of buildings, city, liberties, suburbs, Westminster, Southwark, and altogether; for, as to the particular part called the City, or within the walls, that was not yet much infected; but, in the whole, the face of things, I say, was much altered; sorrow and sadness sat upon every face, and though some part were not yet overwhelmed, yet all looked deeply concerned, and as we saw it apparently coming on, so every one looked on himself and his family as in the utmost danger: were it possible to represent those times exactly, to those that did not see them, and give the reader due ideas of the horror that every-where presented itself, it must make just impressions upon their minds, and fill them with surprise. London might well be said to be all in tears; the mourners did not go about the streets indeed, for nobody put on black, or made a formal dress of mourning for their nearest friends; but the voice of mourning was truly heard in the streets; the shrieks of women and children at the windows and doors of their houses, where their nearest relations were perhaps dying, or just dead, were so frequent to be heard, as we passed the streets, that it was enough to pierce the stoutest heart in the world to hear them. Tears and lamentations were seen almost in every house, especially in the first part of the visitation; for towards the latter end, men's hearts were hardened, and death was so always before their eyes, that they did not so much concern themselves for the loss of their friends, expecting that themselves should be summoned the next hour. As the infection spread, and families under the slightest suspicion were shut up in their houses, the streets became deserted and overgrown with grass, trade and commerce ceased almost wholly, and, although many had succeeded in laying up stores in time, the town soon began to suffer from scarcity of provisions. This was felt the more as the stoppage of trade had thrown workmen and shopmen out of employment, and families reduced their numbers by dismissing many of their servants, so that a great mass of the population was thrown into a state of absolute destitution. This necessity of going out of our houses to buy provisions, was, in a great measure, the ruin of the whole city, for the people catched the distemper, on these occasions, one of another, and even the provisions themselves were often tainted, at least I have great reason to believe so; and, therefore, I cannot say with satisfaction, what I know is repeated with great assurance, that the market-people, and such as brought provisions to town, were never infected. I am certain the butchers of Whitechapel, where the greatest part of the flesh-meat was killed, were dreadfully visited, and that at last to such a degree, that few of their shops were kept open, and those that remained of them killed their meat at Mile-end and that way, and brought it to market upon horses It is true people used all possible precautions; when any one bought a joint of meat in the market, they would not take it out of the butcher's hand, but took it off the hooks them-selves. On the other hand, the butcher would not touch the money, but have it put into a pot full of vinegar, which he kept for that purpose. The buyer carried always small money to make up any odd sum, that they might take no change. They carried bottles for scents and perfumes in their hands, and all the means that could be used were employed; but then the poor could not do even these things, and they went at all hazards. Innumerable dismal stories we heard every day on this very account. Sometimes a man or woman dropped down dead in the very markets; for many people that had the plague upon them knew nothing of it till the inward gangrene had affected their vitals, and they died in a few moments; this caused that many died frequently in that manner in the street suddenly, without any warning; others, perhaps, had time to go to the next bulk or stall, or to any door or porch, and just sit down and die, as I have said before. These objects were so frequent in the streets, that when the plague came to be very raging on one side, there was scarce any passing by the streets, but that several dead bodies would be lying here and there upon the ground; on the other hand, it is observable that though at first, the people would stop as they went along and call to the neighbours to come out on such an occasion, yet, afterwards, no notice was taken of them; but that if at any time we found a corpse lying, go across the way and not come near it; or if in a narrow lane or passage, go back again, and seek some other way to go on the business we were upon; and in those cases the corpse was always left, till the officers had notice to come and take them away; or till night, when the bearers attending the dead-cart would take them up, and carry them away. Nor did those undaunted creatures, who performed these offices, fail to search their pockets, and sometimes strip off their clothes if they were well dressed, as sometimes they were, and carry off what they could get.  As the plague increased in intensity, the markets themselves were abandoned, and the country-people brought their provisions to places appointed in the fields outside the town, where the citizens went to purchase them with extraordinary precautions. There were stations of this kind in Spitalfields, at St. George's Fields in Southwark, in Bunhill-fields, and especially at Islington. The appearance of the town became still more frightful as the summer advanced. 'It is scarcely credible; continues the remarkable writer we are quoting,' what dreadful cases happened in particular families every day; people, in the rage of the distemper, or in the torment of their rackings, which was indeed intolerable, running out of their own government, raving and distracted, and oftentimes laying violent hands upon themselves, throwing themselves out of their windows, shooting them-selves, &c. Mothers murdering their own children, in their lunacy; some dying of mere grief, as a passion; some of mere fright and surprise, without any infection at all; others frightened into idiotism and foolish distractions; some into despair and lunacy; others into melancholy madness. The pain of the swelling was in particular very violent, and to some intolerable; the physicians and surgeons may be said to have tortured many poor creatures even to death. The swellings in some grew hard, and they applied violent drawing plasters or poultices to break them; and, if these did not do, they cut and scarified them in a terrible manner. In some, those swellings were made hard, partly by the force of the distemper, and partly by their being too violently drawn, and were so hard, that no instrument could cut them, and then they burned them with caustics, so that many died raving mad with the torment, and some in the very operation. In these distresses, some, for want of help to hold them down in their beds, or to look to them, laid hands upon themselves, as above; some broke out into the streets, perhaps naked, and would run directly down to the river, if they were not stopped by the watchmen, or other officers, and plunge themselves into the water, wherever they found it. It often pierced my very soul to hear the groans and cries of those who were thus tormented.' 'This running of distempered people about the streets,' Defoe adds, 'was very dismal, and the magistrates did their utmost to prevent it; but, as it was generally in the night, and always sudden, when such attempts were made, the officers could not be at hand to prevent it; and, even when any got out in the day, the officers appointed did not care to meddle with them, because, as they were all grievously infected, to be sure, when they were come to that height, so they were more than ordinarily infectious, and it was one of the most dangerous things that could be to touch them; on the other hand, they generally ran on, not knowing what they did, till they dropped down stark dead, or till they had. exhausted their spirits so, as that they would fall and then die in perhaps half an hour or an hour; and, which was most piteous to hear, they were sure to come to themselves entirely in that half hour or hour, and then to make most grievous and piercing cries and lamentations, in the deep afflicting sense of the condition they were in.' 'After a while, the fury of the infection appeared to be so increased that, in short, they shut up no houses at all; it seemed enough that all the remedies of that kind had been used till they were found fruitless, and that the plague spread itself with an irresistible fury, so that it came at last to such violence, that the people sat still looking at one another, and seemed quite abandoned to despair. Whole streets seemed to be desolated, and not to be shut up only, but to be emptied of their inhabitants; doors were left open, windows stood shattering with the wind in empty houses, for want of people to shut them; in a word, people began to give up themselves to their fears, and to think that all regulations and methods were in vain, and that there was nothing to be hoped for but an universal desolation.' In spite of this horrible state of things, the town was filled with men desperate in their wickedness; robbers and murderers prowled about in search of plunder, and riotous people, as if in despair, indulged more than ever in their vices. One house, in special, the Pye Tavern, at the end of Houndsditch, was the haunt of men who openly mocked at religion and death. In the middle of these scenes, two incidents occurred of an almost ludicrous character. Such is the story of the piper, which Defoe appears to have heard from one of the men who carted the dead to the burial-places, whose name was John Hayward, and in whose cart the accident happened. It was under this John Hayward's care,' he says, and within his bounds, that the story of the piper, with which people have made themselves so merry, happened, and he assured me that it was time. It is said that it was a blind piper; but, as John told me, the fellow was not blind, but an ignorant, weak, poor man, and usually went his rounds about ten o'clock at night, and went piping along from door to door, and the people usually took him in at public-houses where they knew him, and would give him drink and victuals, and sometimes farthings; and he in return would pipe and sing, and talk simply, which diverted the people, and thus he lived. It was but a very bad time for this diversion, while things were as I have told, yet the poor fellow went about as usual, but was almost starved; and when anybody asked how he did, he would answer, the dead cart had not taken him yet, but that they had promised to call for him next week. It happened one night that this poor fellow, whether somebody had given him too much drink or no (John Hayward said he had not drink in his house, but that they had given him a little more victuals than ordinary at a public-house in Colman Street), and the poor fellow having not usually had a bellyfull, or, perhaps, not a good while, was laid all along upon the top of a bulk or stall, and fast asleep, at a door in the street near London-wall, towards Cripplegate, and that, upon the same bulk or stall, the people of some house in the alley, of which the house was a corner, hearing a bell, which. they always rung before the cart came, had laid a body really dead of the plague just by him, thinking, too, that this poor fellow had been a dead body as the other was, and laid there by some of the neighbours. Accordingly, when John Hayward with his bell and the cart came along, finding two dead bodies lie upon the stall, they took them up with the instrument they used, and threw them into the cart; and all this while the piper slept soundly. From hence they passed along, and took in other dead bodies, till, as honest John Hayward told me, they almost buried him alive in the cart, yet all this while he slept soundly; at length the cart came to the place where the bodies were to be thrown into the ground, which, as I do remember, was at Mountmill; and, as the cart usually stopped some time before they were ready to shoot out the melancholy load. they had in it, as soon as the cart stopped, the fellow awaked, and struggled a little to get his head out from among the dead bodies, when, raising himself up in the cart, he called out, 'Hey, where am I?' This frighted the fellow that attended about the work, but, after some pause, John Hayward recovering himself, said: 'Lord bless us! there's somebody in the cart not quite dead! ' So another called to him, and said: 'Who are you?' The fellow answered: 'I am the poor piper: where am I?' 'Where are you I' says Hayward: 'why, you are in the dead cart, and. we are going to bury you.' 'But I an't dead, though, am I?' says the piper; which made them laugh a little, though, as John said, they were heartily frightened at first; so they helped the poor fellow down, and he went about his business. The number of deaths in the week ending the 19th September, was upwards of ten thousand. The weather then began to change, and the air became cooled and purified by the equinoctial winds. It took a good part of the whiter, how-ever, to allay the infection entirely, and it was only late in December that the people who had fled began to crowd back to the metropolis. The king and court only returned at the beginning of the following February. It has been calculated that considerably above a hundred thousand persons perished by this terrible visitation. |