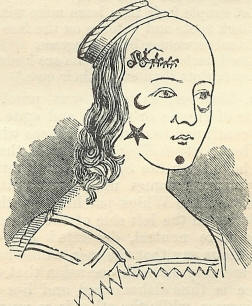

19th NovemberBorn: Charles I of England, 1600, Dunfermline; Albert Thorwaldsen, great Danish sculptor, 1770. Died: Caspar Scioppius, scholar and polemical writer, 1649, Padua; Nicolas Poussin, painter, 1665, Rome; John Wilkins, bishop of Chester, philosopher and writer, 1672, Chancery Lane, London; The Man in the Iron Mask, 1703, Bastille; Abraham John Valpy, editor of classics, 1854, London. Feast Day: St. Pontian, pope and martyr, about 235. St. Barlaam, martyr, beginning of 4th century. St. Elizabeth of Hungary, widow, 1231. PATCHING AND PAINTING The beauties of the court of Louis Quinze thought they had made a notable discovery, when they gummed pieces of black taffeta on their cheeks to heighten the brilliancy of their complexions; but the fops of Elizabethan England had long before anticipated them, by decorating their faces with black stars, crescents, and lozenges: To draw an arrant fop from top to toe, Whose very looks at first clash shew him so; Give him a mean, proud garb, a dapper grace, A pert dull grin, a black patch cross his face. And the fashion prevailed through succeeding reigns, for Glapthorne writes in 1640: If it be a lover's part you are to act, take a black spot or two; twill make your face more amorous, and appear more gracious in your mistress's eyes. The earliest mention of the adoption of patching by the ladies of England, occurs in Bulwer's Artificial Changeling (1653). Our ladies, he complains, have lately entertained a vain custom of spotting their faces, out of an affectation of a mole, to set off their beauty, such as Venus had; and it is well if one black patch will serve to make their faces remarkable, for some fill their visages full of them, varied into all manner of shapes. He gives a cut (which we copy) of a lady's face patched in the then fashionable style, of which it might well be sung: Her patches are of every cut, For pimples and for scars; Here's all the wandering planets' signs, And some of the fixed stars. The coach and horses patch was an especial favourite. The author of England's Vanity (1653) is goaded thereby into a kind of grim humour: Methinks the mourning coach and horses all in black, and plying on their foreheads, stands ready harnessed to whirl them to Acheron, though I pity poor Charon for the darkness of the night, since the moon on the cheek is all in eclipse, and the poor stars on the temples are clouded in sables, and no comfort left him but the lozenges on the chin, which, if he please, he may pick off for his cold. Mr. Pepys has duly recorded his wife's first appearance in patches, which seems to have taken place without his concurrence, as three months afterwards he makes an entry in his Diary: My wife seemed very pretty today, it being the first time I had given her leave to wear a black patch. And a week or two later, he declares that his wife, with two or three patches, looked far handsomer than the Princess Henrietta. Lady Castlemaine, whose word was law, decreed that patches could not be worn with mourning; but they seem to have been held proper on all other occasions, being worn in the afternoon at the theatre, in the parks in the evening, and in the drawing room at night. Puritanical satirists, of course, did not leave the fair patchers unmolested. One Smith printed An Invective against Black Spotted Faces, in which he warned them: Hell gate is open day and night To such as in black spots delight. If pride their faces spotted make, For pride then hell their souls will take. If folly be the cause of it, Let simple fools then learn more wit. Black spots and patches on the face To sober women bring disgrace. Lewd harlots by such spots are known, Let harlots then enjoy their own. Fashion, however, as usual, was proof against the assaults of rhyme or reason, and spite of both, the ladies continued to cover their faces with black spots. When party feeling ran high in the days of Anne, we have it on the Spectator's authority, that: politically minded dames used their patches as party symbols: the Whigs patching on the right, and the Tories on the left side of their faces, while those who were neutral, decorated both cheeks. The censorious say that the men whose hearts are aimed at, are very often the occasion that one part of the face is thus dishonoured and lies under a kind of disgrace, while the other is so much set off and adorned by the owner; and that the patches turn to the right or to the left according to the principles of the man who is most in favour. But whatever may be the motives of a few fantastic coquettes, who do not patch for the public good so much as for their own private advantage, it is certain that there are several women of honour who patch out of principle, and with an eye to the interests of their country. Nay, I am informed that some of them adhere so steadfastly to their party, and are so far from sacrificing their zeal for the public to their passion for any particular person, that in a late draught of marriage articles, a lady has stipulated with her husband that whatever his opinions are, she shall be at liberty to patch on which side she pleases. This was written in 1711, and in 1754 the patch was not only still in existence, but threatening to overwhelm the female face altogether. A writer in the World for that year says: Though I have seen with patience the cap diminishing to the size of a patch, I have not with the same unconcern observed the patch enlarging itself to the size of a cap. It is with great sorrow that I already see it in possession of that beautiful mass of blue which borders upon the eye. Should it increase on the side of that exquisite feature, what an eclipse have we to dread! but surely it is to be hoped the ladies will not give up that place to a plaster, which the brightest jewel in the universe would want lustre to supply. . . . All young ladies, who find it difficult to wean themselves from patches all at once, shall be allowed to wear them in whatever number, size, or figure they please, on such parts of the body as are, or should be, most covered from sight. And any lady who prefers the simplicity of such ornaments to the glare of her jewels, shall, upon disposing of the said jewels for the benefit of the foundling or any other hospital, be permitted to wear as many patches on her face as she has contributed hundreds of pounds to so laudable a benefaction, and so the public be benefited, and patches, though not ornamental, be honourable to see.' This valuable suggestion was lost upon the sex, for Anstey enumerates: Velvet patches la grecque, among a fine lady's necessities in 1766; they seem, however, to have fallen from their high estate towards the beginning of the present century, for the books of fashion of that period make no allusion to them whatever, but they did not become utterly extinct even then. A writer in 1826, describing the toilet table of a Roman lady, says: It looks nearly like that of our modern belles, all loaded with jewels, bodkins, false hair, fillets, ribbands, washes, and patch boxes; and the present generation may possibly witness a revival of the fashion, as it has witnessed the reappearance of the ridiculous, ungraceful, intrusive hoop petticoat. Long as patching lasted, it was but a thing of a day compared with the more reprehensible custom of painting a custom common to all ages, and pretty nearly all countries, since Jezebel painted her face and tired her head and looked out at a window, as the avenging Jehu entered in at the gate. There is evidence of Englishwomen using paint as early as the fourteenth century, and the practice seems to have been common when Shakespeare tried his prentice hand on the drama. In his Love's Labour's Lost, he makes the witty Biron ingeniously defend his dark lady love: If in black my lady's brow be decked, It mourns that painting and usurping hair, Should ravish doters with a false aspect And therefore is she born to make black fair. Her favour turns the fashion of the days; IFor native blood is counted painting now; And therefore red that would avoid dispraise, IPaints itself black to imitate her brow. And when bitter Philip Stubbs complains that his countrywomen are not contented with a face of heaven's making, but must adulterate the Lord's workmanship with far fetched, dear bought liquors, unguents, and cosmetics, the worthy Puritan only echoes Hamlet's reproach: I have heard of your paintings too, well enough. God hath given you one face, and you make yourselves another. When Sir John Harrington declared he would rather salute a lady's glove than her lip or her cheek, he justified his seeming bad taste with the rhymes: If with my reason you would be acquainted, Your gloves perfumed, your lip and cheek are painted. Overbury describes a lady of the period as reading her face in the glass every morning, while her maid stood by ready to write 'red' here, and blot out pale there, till art had done its best or worst. No wonder the ,Stedfast Shepherd exclaims: Shew me not a painted beauty, Such impostures I defy! Court ladies, nevertheless, continued to wear artificial red and white, till the court itself was banished from England. As long as the Commonwealth existed, no respectable woman dared to paint her cheeks; but Charles H. had not been a year at Whitehall, before the practice was revived, to the disgust of Evelyn and the discontent of Pepys. The latter vows he loathes Nelly Gwyn and Mrs. Knipp (two of his especial favourites), and hates his relative, pretty Mrs. Pierce, for putting red on their faces. Bulwer says: Sometimes they think they have too much colour, then they use art to make them pale and fair; now they have too little colour, then Spanish paper, red leather, or other cosmetical rubrics must be had. A little further on he accuses the gallants of beginning to vie patches and beauty spots, nay, painting, with the tender and fantastical ladies. Among these fantastical dames, we are sorry to say, Waller's Saccharissa must be numbered. The poet complains: Pygmalion's fate reversed is mine; His marble love took flesh and blood; All that I worshipp'd as divine, That beauty! now 'tis understood, Appears to have no more of life Than that whereof he framed his wife. Saccharissa deserved the reproaches of her lover more than Mary of Modena did the rebukes of her confessor, for she rouged, contrary to her own inclination, merely to please her husband. Painting flourished under Anne. An unfortunate husband writes to the Spectator in 1711, asking, if it be the law that a man marrying a woman, and finding her not to be the woman he intended to marry, can have a separation, and whether his case does not come within the meaning of the statute. Not to keep you in suspense, he says; as for my dear, never man was so enamoured as I was of her fair forehead, neck, and arms, as well as the bright jet of her hair; but to my great astonishment, I find they were all the effect of art. Her skin is so tarnished with this practice, that when she first wakes in a morning, she scarce seems young enough to be the mother of her whom I carried to bed the night before. I shall take the liberty to part with her by the first opportunity, unless her father will make her portion suitable to her real, not her assumed countenance. The Spectator enters there upon into a description of the Picts, as he calls the painted ladies. The Picts, though never so beautiful, have dead, uninformed countenances. The muscles of a real face sometimes work with soft passions, sudden surprises, and are flushed with agreeable confusions, according as the object before them, or the ideas presented to them, affect their imaginations. But the Picts behold all things with the same air, whether they are joyful or sad; the same fixed insensibility appears on all occasions. A Pict, though she takes all that pains to invite the approach of lovers, is obliged to keep them at a certain distance; a sigh in a languishing lover, if fetched too near, would dissolve a feature; and a kiss snatched by a forward one, might transform the complexion of the mistress to the admirer. It is hard to speak of these false fair ones without saying something uncomplaisant, but it would only recommend them to consider how they like coming into a room newly painted; they may assure themselves the near approach of a lady who uses this practice is much more offensive. If Walpole is to be believed, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu not only used the cheapest white paint she could get, but left it on her skin so long, that it was obliged to be scraped off her. More than one belle of his time killed herself with painting, like beautiful Lady Coventry, whose husband used to chase her round the dinner table, that he might remove the obnoxious colour with a napkin! Would that we could say that rouge, pearl powder, and the whole tribe of cosmetics were strangers to the toilet tables of our own day a glance at the shop window of a fashionable perfumer forbids us laying the flattering unction to our soul, that ladies no longer strive to: With curious arts dim charms revive, And triumph in the bloom of fifty five; and tempts us, in the words of an old author, to exclaim: From beef without mustard, from a servant who overvalues himself, and from a woman who painteth herself, good Lord, deliver us! |