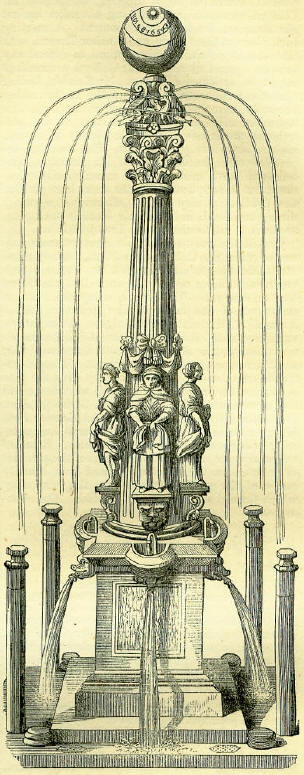

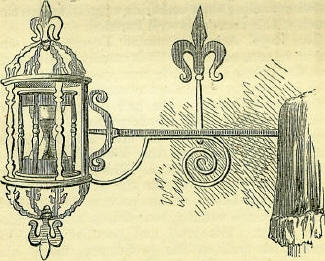

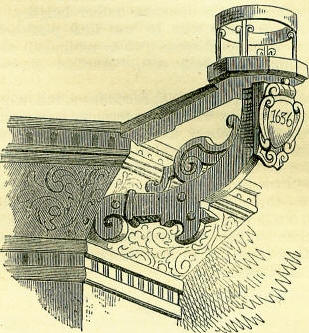

18th DecemberBorn: Prince Rupert, military commander, 1619, Prague. Bieck Died: Robert Nanteuil, celebrated engraver, 1678, Paris; Heneage Pinch, Earl of Nottingham, 1682; Veit Ludwig von Seckendorf, political and theological writer, 1692, Halle; Soame Jenyns, religious and general writer, 1787; Pierre Louis de Préville, celebrated French comedian, 1799; Johann Gottfried Von Herder, German theologian and philosopher, 1803; Dr. Alexander Adam, eminent classic scholar and teacher, 1809, Edinburgh; Thomas Dunham Whitaker, antiquarian writer, 1821, Blackburn; General Lord Lynedoch, 1843, London: Samuel Rogers, poet, 1855, London. Feast Day: Saints Rufus and Zozimus, martyrs, 116. St. Gatian, first bishop of Tours, confessor, about 300. St. Winebald, abbot, and confessor, 760. SUN-DIALS AND HOUR-GLASSESWhen the philanthropist Howard was on his death-bed, he said: 'There is a spot near the village of Dauphiney, where I should like to be buried; suffer no pomp to be used at my funeral, no monument to mark the spot where I am laid; but put me quietly in the earth, place a sun-dial over my grave, and let me be forgotten.' A similar affection was evinced by Sir William Temple, who desired that his heart might be placed in a silver box and deposited under the sun-dial in his garden, where he had experienced so much pleasure in contemplating the works of nature. Sun-dials are of very ancient date, and the honour of inventing them is claimed for the Phoenicians. The earliest mention of them occurs in the well-known incident recorded in Scripture of King Hezekiah, who, when sick and penitent, is granted, in miraculous evidence of the Lord's intention to restore him to health, that the shadow shall go backward ten degrees on the sun-dial of Ahaz. Homer, too, often supposed to be a contemporary of Hezekiah, states, in his Odyssey, that there was a dial in the Island of Syra, upon which was represented the sun's annual race. Two centuries ago, sun-dials attracted more attention than they do at the present time. The great sculptor, Nicholas Stone, mentions, under date 1619, the making of a dial at St. James's, the king finding stone and workmanship only, for the which he had £6, 13s. 4d. 'And in 1622,' he says: I made the great diall in the privy-garden, at Whitehall, for the which I had £46.' 'And in that year, 1622,' he continues, 'I made a diall for my Lord Brook, in Holbourn, for the which I had £8, 10s. And for Sir John Daves, at Chelsey, he made a dial and two statues of an old man and a woman, for which he received £7 a piece.  In Joseph Moxon's Tutor to Astronomic and Geographic, or An easie way to know the use of both the Globes (1659), there are ample directions for the making of sun-dials of many various kinds, and among others: a solid ball or globe that will shew the hour of the day without a gnomon. The principle followed in this case, was to have a globe marked round. the equator with two series of numbers from 1 to 12, and to erect it, rectified for the latitude, with one of the 12's set to the north, the other to the south. When the sun shone on this globe, the number found under the place where the shadowed and illuminated parts met, was the hour of the day. Mr. Moxon has fortunately given us a representation, here copied, of a dial of this kind perched on the top of a columnar fountain, which was erected by Mr. John Leak, at Leadenhall Corner, in London, in the mayoralty of Sir John Dethick, knight, and thus has preserved to us, incidentally, an object much more important than the dial-namely, a beautiful fountain which once adorned one of the principal thoroughfares of the metropolis, furnishing those supplies of healthful beverage which the charity of our age has again offered through the medium of our so-called ' drinking fountains.' However invaluable sun-dials might be as chronometers, they could only be of use in daylight, and when the sun was actually shining. Some mode had to be devised for supplying their place in cloudy weather, at night, or within doors. One contrivance employed by the ancients for this end was the clepsydra, or water-clock, which noted the passing of time by the escape of water through a vessel, with a hole at the bottom, into a cistern beneath. Another method, designed on a similar principle, was that of the hour-glass, by which the lapse of time was ascertained through the passing of a small quantity of sand from the upper to the lower part of the glass. Hour-glasses are said to have been invented at Alexandria about the middle of the third century, and we are informed that persons used to carry them about as we do watches. They are familiar to us as an accompaniment, in pictorial representations, of the solitary monk or anchorite, where the hour-glass is generally exhibited along with the skull and crucifix. They were also attached to pulpits, in order to regulate the length of sermons. But this last mode of employing hour-glasses seems to have been chiefly introduced after the Reformation, when long sermons came much into fashion. Previous to that period, pulpit-discourses appear to have been generally characterised by brevity. Many of St. Austin's might be easily delivered in ten minutes; nor was it usual in the church to devote more than half an hour to the most persuasive eloquence. These old sermons were of the nature of homilies, and it was only when the church felt called upon to explain tenets attacked, or eliminate doctrinal disputes, that they altered in character; and the pulpit became a veritable 'drum-ecclesiastic.' From the days of Luther, the length of sermons increased, until the middle of the seventeenth century; when the Puritan preachers inflicted discourses of two hours or more in duration on their hearers. In some degree to regulate these enthusiastic talkers, hour-glasses were placed upon the desks of their pulpits, and in 1623, we read of a preacher 'being attended by a man that brought after him his book and hour-glass.' Some churches were provided with half-hour glasses also, and we may imagine the anxiety with which the clerk would regard the choice made by the parson, as upon this would depend the length of his attendance. >L'Estrange tells an amusing story of a parish clerk, who had sat patiently under a preacher, 'till he was three-quarters through his second glass,' and the auditory had slowly withdrawn, tired out by his prosing; the clerk then arose at a convenient pause in the sermon, and calmly requested 'when he had clone,' if he would be pleased to close the church-door, 'and push the key under it,' as himself and the few that remained were about to retire.  In the sixteenth century, pulpits began to be regularly furnished, with iron-work stands, for the reception of the hour-glass. One of these in Compton Bassett Church, Wilts, is here represented; the large fleur-de-lys, in the centre of the iron bar, acts as a handle by which the hour-glass may be turned in its stand. Sometimes these stands and glasses were very elaborate in design, and of costly materials. At Hurst, in Berkshire, is a wrought-iron work of the kind most intricately designed. It has the date 1636, and the words, 'as this glass runneth, so man's life passeth,' amid foliations of oak and ivy. The frame of the hour-glass of St. Dunstan's, Fleet Street, was of solid silver, and contained enough of the precious metal to be melted clown, and converted into staff-heads for the parish beadles.  The lonely church of Cliffe, on the Kentish coast, between Gravesend and the Nore, furnishes us with a second example of the stand alone. The pulpit is of carved wood, dated 1634. This stand is affixed thereto by a bracket, which bears upon the shield the date 1636. It is on the preacher's left side. In the book of St. Katherine's Church, Aldgate, date 1564, we find, 'Paid for an Hour-glass that hangeth by the pulpit where the preacher doth make a sermon, that he may know how the hour passeth away, one shilling;' and in the same book, among the bequests of date 1616, is 'an hewer-glass with a frame of irone to stand in.' In the time of Cromwell, the preacher, having named the text, turned up the glass; and if the sermon did not last till the sand had run down, it was said by the congregation that the preacher was lazy; but if, on the other hand, he exceeded this limit, they would yawn and stretch themselves till he had finished. Many humorous stories originated from this clerical usage. There is a print of Hugh Peter's preaching, holding up the hour-glass, as he utters the words, 'I know you are good-fellows, so let's have another glass!' A similar tale is told of Daniel Burgess, the celebrated Nonconformist divine, at the beginning of the last century. Famous for the length of his pulpit harangues, and the quaintness of his illustrations, he was at one time declaiming with great vehemence against the sin of drunkenness, and in his ardour had fairly allowed the hour-glass to run out before bringing his discourse to a conclusion. Unable to arrest himself in the midst of his eloquence, he reversed the monitory horologe, and exclaimed, 'Brethren. I have somewhat more to say on the nature and consequences of drunkenness, so let's have the other glass-and then I'-the usual phrase adopted by topers at protracted sittings. Mr. James Maidment, in his Third Book of Scottish Pasquils, has given a somewhat similar anecdote. 'A humorous story,' he observes, 'has been preserved of one of the Earls of Airly, who entertained at his table a clergyman, who was to preach before the Commissioner next day. The glass circulated, perhaps, too freely; and whenever the divine attempted to rise, his lordship prevented him, saying: 'Another glass-and then!' After conquering his lordship, his guest went home. The next day the latter selected as his text, 'The wicked shall be punished and right airly!' Inspired by the subject, he was by no means sparing of his oratory, and the hour-glass was disregarded, although he was repeatedly warned by the precentor, who, in common with Lord Airly, thought the discourse rather lengthy. The latter soon knew why he was thus punished, by the reverend gentleman when reminded) always exclaiming, not sotto voce, 'Another glass-and then! '' Fosbroke, in his British Monachism, tells a quaint tale of a mode by which long sermons were avoided: A rector of Bibury used to preach two hours, regularly turning the glass. After the text, the esquire of the parish withdrew, smoked his pipe, and returned to the blessing. Hogarth, in his 'Sleeping Congregation,' has introduced an hour-glass on the left-hand side of the preacher. They lingered in country churches; but they ceased to be in anything like general use after the Restoration. |