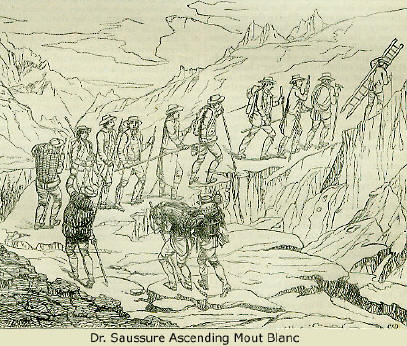

17th FebruaryBorn: Francis Duke of Guise, French warrior, 1519; Horace Benedict de Saussure, Genevese traveller, 1740; John Pinkerton, historian and antiquary, 1758, Edinburgh. Died: Michael Angelo Buonarotti, painter, sculptor, architect, and engineer, 1563-4; Giordano Bruno, Neapolitan philosopher, burnt at Rome, 1600; Jean Baptiste Poquelin Molière, 1673, Paris; Antoine Galland, translator of the Arabian Nights' Entertainments, 1715; John Martin, historical painter, 1854; John Braham, singer and composer, 1856, London. Feast Day: Saints Theodulus and Julian, martyrs in Palestine, 309. St. Flavian, archbishop of Constantinople, martyr in Lydia, 449. St. Leman, or Luman, first bishop of Trim, 5th century. St. Fintan, abbot in Leinster, 6th century. St. Silvia, of Auchy, bishop, 718. MOLIÈREFrance, having Molière for one of her sons, may be said to have given birth to the greatest purely comic writer of modern times. Born the son of a humble valet-de-ehambre and tapissier in Paris, in 1620, this singular genius pressed through all the trammels and difliculties of his situation, to education and the exercise of that dramatic art in which he was to attain such excellence. The theatre was new in the French capital, and he at once raised it to glory. His Etourdi, his Precieuses Ridicules, his Menteur, his Tartuffe, his Femmes Savantes, what a brilliant series they constitute! The list is closed by the Malade Imaginaire, which came before the world . when the poor author was sick in earnest; dying indeed of a chest complaint, accompanied by spitting of blood. On the third night of the representation, he was advised not to play; but he resolved to make the effort, and it cost him his life. He was carried home dying to his house in the Rue Richelieu, and there soon breathed his last, choked with a gush of blood, in the arms of two stranger priests who happened to lodge in the same house. It was maliciously reported by prejudiced people that Molière had expired when in the net of counterfeiting death in his idle on the stage, and this made it the more difficult to obtain for him the Christian burial usually denied to players. His widow flew to the king. exclaiming against the priesthood, but was glad to make very humble representations to the Archbishop of Paris, and to stretch a point regarding Molière wish for religious consolations, in order to have the remains of her husband treated decently. On its being shown that he had received the sacrament at the preceding Easter, the archbishop was pleased to permit that this glory of France should be inhumed without any pomp, with two priests only, and with no church solemnities. The Revolutionists, more just, transferred the remains of the great comedian from the little chapel where they were first deposited to the Museum of French Monuments. M. GALLANDThe English people, who for generations have enjoyed that most attractive book, the Arabian Nights' Entertainments, know in general very little of its origin. The western world received it from the hands of a French savant of the seventeenth century, who obtained it in its original form during a residence in the East. The history of Tartufe is a curious example of the impediments so frequently thrown in the way of genius. The whole of the play was not publicly performed until after a severe struggle with the bigots of Paris, the first three acts only having been produced at Versailles on the 12th of May 1664, but not the complete play until 1669. It took five years to convince the religiously-affected that an attack on the immoral pretender to religious fervour was not an attack on religion. It may easily be supposed that a character so symbolical of cant and duplicity, under whatever creed it might choose to cloak itself, would soon be transferred to other countries, and consequently we find it transplanted to our own theatre as early as 1670, by a comedian of the name of Medbourne, a Roman Catholic, who in his adaptation chose to make the Tarttaffe a French Huguenot, thereby gratifying his own religious prejudices, and more closely satirizing the English puritan of the time. Ozell, a dramatic writer, known only to literary antiquaries and the readers of the Duncied, also translated it, with the rest of Moliere's dramatic works; but the chief introducer and adapter of this celebrated play to the. English stage was Colley Cibber, who, in 1718, under the name of the Non-Jeerer, produced and wrote the principal part of what is now known as The Hypocrite, Isaac Bickerstaffe doing little more than adding the coarse character of Mawworm for Weston, the chief low comedian of his time.'-Anonymous. Antoine Galland, born of poor parents in 1646, showed such talents in early life that he not only obtained a finished education, but received an appointment as attaché to the French embassy at Constantinople while still a young man. He devoted himself to Oriental travel, the collection of Oriental literature, and the study of Eastern authors. His learning was as prodigious in amount as its subjects were for that age extra-ordinary: but of all his laborious works little memory survives, while his light task of translating the Mille et Une Nuits has ensured him a kind of immortality. In the first editions of this work, the translator preserved the whole of the repetitions respecting Schecherezade and her vigilant sister: which the quick-witted French found insufferably tedious. It was resolved by some young men that they would try to make Galland feel how stupid were these endless wakenings. Coming in the middle of a cold January night to his house in the Faubourg St. Jacques, they began to cry vehemently for M. Galland. He speedily appeared upon the balcony, dressed only in his robe de chambre and night-cap, and in great anger at this inopportune disturbance. 'Have I the honour,' said one of the youths, 'to speak to Monsieur Galland - the. celebrated Monsieur Galland-the learned translator of the Mille et Une Nuits?' 'I am he, at your service, gentlemen,' cried the savant, shivering from top to toe. 'Ah then, Monsieur Galland, if you are not asleep, I pray you, while the day is about to break, that you will tell us one of those pleasant stories which you so well know.' The hint was taken, and the tiresome formula of the wakening of the sultancss was suppressed in all but the first few nuits. DE SAUSSURE'S ASCENT OF MONT BLANCM. de Saussure was a Geneva professor, who distinguished himself in the latter part of the eighteenth century by his researches in the natural history of the Alps. His investigations were embodied in a laborious work, entitled Voyage clans les Alpes, which yet bears an honoured place in European libraries. Previous to De Saussure's time, there had been scarcely any such bold idea entertained as that the summit of Mont Blanc could be reached by human foot. Under his prompting, a few guides made the attempt on three several occasions, but without success. The great difficulty lay in the necessity of under-going the whole exertion required within the time between two indulgences in repose, for there was no place where, in ascending or descending, the shelter necessary for sleep could be obtained. The case might well appear the more hopeless, when the extraordinary courage and powers of exertion and endurance that belong to the Alpine guides were considered: if they generally regarded the enterprise as impossible, who might attempt it? Nevertheless, a now and favourable route having been discovered, and a hut for shelter during an intermediate night having been prepared, M. de Saussure attempted an ascent in September 1785. Having spent a night at the hut, the party set out next morning with groat confidence to ascend the remaining thousand toises along the ridge called the 'Aiguille du Goute': and they had advanced a considerable way when the depth of the fresh-fallen snow proved an insurmountable barrier. A second attempt was made by De Saussure in June 1786: and, though it failed, it led to the discovery, by a guide named Jacques Balmat, of a preferable route, which proved to be the only one at all practicable. Unfortunately, De Saussure, who, from his persevering efforts, deserved to be the Conqueror of Mont Blanc, was anticipated in the honour by a gentle-man named Paccard, to whom Balmat imparted his secret, and who, under Balmat's guidance, gained the summit of the mountain in August of the last-named year.  It was not till August 1787, and after a second successful attempt by Balmat, in company with two other guides, that De Saussurc finally accomplished his object. On this occasion, he had a tent carried, in which he might take a night's rest at whatever place should prove suitable: and all his other preparations were of the most careful kind. The accompanying illustration, which is from his own work, exhibits the persevering philosopher calmly ascending along the icy track, with his corlége of guides, and certain men carrying his tent, his scientific instruments, and other articles. It ill be observed that the modern expedient of tying the members of the party together had not then been adopted: but some of them held by each other's alpenstocks, as is still the fashion. De Saussure spent the first night on the top of a comparatively small mountain called the Cote, near Chamouni: the second was passed in an excavation in the snow on what was called the second plateau, with the tent for a covering. On the third day, the party set out at an early hour, undauntedly climbing a snow or ice slope at an angle of thirty-nine degrees, and at eleven o'clock gained the summit, after suffering incredible inconvenience from the heat and the rarity of the air. To give an idea of the latter difficulty, it is only necessary to mention that De Saussure, by his barometer, found the column of the atmosphere above him represents by sixteen inches and one line. 'My first looks,' says he, 'were directed on Chamouni, where I knew my wife and her two sisters were, their eyes fixed to a telescope, following all our stops with an uneasiness too great, without doubt, but not less distressing to them, I felt a very pleasing and consoling sentiment when I saw the flag which they had promised to hoist the moment they observed me at the summit, when their apprehensions would be at least suspended.' All Europe rang with the news of De Sanssure's ascent of Mont Blanc and his observations on the mountain; and it was long before he found many followers. Now scarcely a season passes but some enterprising Englishman performs this once almost fabulous feat. JOHN BRAHAMIt is hardly conceivable that this famous vocalist died so recently as 1856, for one occasionally meets with his figure in favourite characters as the frontispiece of plays dating in the eighteenth century. There is scarcely anybody so old as to remember when Braham was a new figure on the stage. In reality, he did appear there so long ago as 1785, when, however, he was only eleven years of age. He was of Hebrew parentage, was a worthy and respected man, and joined to the wonderful powers of his voice a very fair gift of musical composition. The large gains he made in his own proper walk he lost, as so many have done, by going out of it into another--that of a theatre-proprietor. But his latter clays were passed in comfort, under the fostering care of his daughter, the Countess Waldegrave. MYSTIC MEMORYIn February 1828, Sir Walter Scott was breaking himself down by over-hard literary work, and had really fallen to some extent out of health. On the 17th he enters in his Diary, that, on the preceding day at dinner, although in company with two or three beloved old friends, he was strangely haunted by what he would call 'the sense of preexistence: 'namely, a confused idea that nothing that passed was said for the first time-that the same topics had been discussed, and the same persons had stated the same opinions on them. The sensation, he add, 'was so strong as to resemble what is called a mirage in the desert, or a calenture on board of ship, when lakes are seen in the desert, and sylvan landscapes in the sea. There was a vile sense of want of reality in all that I did and said.' This experience of Scott is one which has often been felt, and often commented on by authors, by Scott himself amongst others. In his novel of Guy Mannering, he represents his hero Bertram as returning to what was, unknown to him, his native castle, after an absence from childhood, and thus musing on his sensations: 'Why is it that some scenes awaken thoughts which belong, as it were, to dreams of early and shadowy recollection, such as my old Brahmin Moonshie would have ascribed to a state of previous existence: How often do we find ourselves in society which we have never before met, and yet feel impressed with a mysterious and ill-defined consciousness that neither the scene, the speakers, nor the subject are entirely new: nay, feel as if we could anticipate that part of the conversation which has not yet taken place.' Warren and Bulwer Lytton make similar remarks in their novels, and Tennyson adverts to the sensation in a beautiful sonnet: As when with downcast eyes we muse and brood, And ebb into a former life, or seem To lapse far back in a confused dream To states of mystical similitude: If one bat speaks, or hems, or stirs his chair, Ever the wonder waxeth more and more, So that we say, All this hath been before. All this hath been, I know not when or where: So, friend, when first I looked upon your face, Our thoughts gave answer each to each, so true Opposed mirrors each reflecting each Although I knew not in what time or place, Methought that I: had often met with you, And each had lived in the other's mind and speech. Theological writers have taken up this strange state of feeling as an evidence that our mental part has actually had an existence before our present bodily life, souls being, so to speak, created from the beginning, and attached to bodies at the moment of mortal birth. Glanvil and Henry More wrote to this effect in the seventeenth century: and in 1762, the Rev Capel Berrow published a work entitled A Pre-existent Lapse of human Souls demonstrated. More recently, we find Southey declaring: 'I have a strong and lively faith in a state of continued consciousness from this stage of existence, and that we shall recover the consciousness of some lower stages through which we may preciously have passed seems to me not improbable.' Wordsworth, too, founds on this notion in that fine poem where he says: Our birth is but a sleep and a forgetting; The soul that rises in us, our life's star, Has had elsewhere its setting, And cometh from afar. With all respect for the doctrine of a previous existence, it appears to us that the sensation in question is no sort of proof of it: for it is clearly absurd to suppose that four or five people who had once lived before, and been acquainted with each other, had by chance got together again, and in precisely the same circumstances as on the former occasion. The, notion, indeed, cannot for a moment be seriously maintained. We must leave it aside, as a mere poetical whimsy. In a curious book, published in 1844 by Dr. Wigan, under the title of The Duality of the Mind, an attempt is made to account for the phenomenon in a different way. Dr. Wigan was of opinion that the two hemispheres of the brain had each its distinct power and action, and that each often acts singly. Before adverting to this theory of the illusion in question, let its hear a remarkably well described case which he brings forward as part of his own experience: 'The strongest example of this delusion I ever recollect in my own person was on the occasion of the funeral of the Princess Charlotte. The circumstances connected with that event formed in every respect a most extraordinary psychological curiosity, and afforded an instructive view of the moral feelings pervading a whole nation, and shewing themselves without restraint or disguise. There is, perhaps, no example in history of so intense and so universal a sympathy, for almost every conceivable misfortune to one party is a source of joy, satisfaction, or advantage to another. One mighty all-absorbing grief possessed the nation, aggravated in each individual by the sympathy of his neighbour, till the whole people became infected with an amiable insanity, and incapable of estimating the real extent of their loss. No one under five-and-thirty or forty years of age can form a conception of the universal paroxysm of grief which then superseded every other feeling. I had obtained permission to be present on the occasion of the funeral, as one of the lord chamberlain's staff. Several disturbed nights previous to that ceremony, and the almost total privation of rest on the night immediately preceding it, had put my mind into a state of hysterical irritability, which was still further increased by grief and by exhaustion from want of food; for between breakfast and the hour of interment at midnight, such was the confusion in the town of Windsor, that no expenditure of money could procure refreshment. 'I had been standing four hours, and on taking my place by the side of the coffin, in St. George's chapel, was only prevented from fainting by the interest of the scene. All that our truncated ceremonies could bestow of pomp was there, and the exquisite music produced a sort of hallucination. Suddenly after the pathetic Miserere of Mozart, the music ceased, and there was an absolute silence. The coffin, placed on a kind of altar covered with black cloth (united to the black cloth which covered the pavement), sank down so slowly through the floor, that it was only ill measuring its progress by some brilliant object beyond it that any motion could be perceived. I had fallen into a sort of torpid reverie, when I was recalled to consciousness by a paroxysm of violent grief on the part of the bereaved husband, as his eye suddenly caught the coffin sinking into its black grave, formed by the inverted covering of the altar. In an instant I felt not merely an impression, but a conviction that I had seen the whole scene before on some former occasion, and had heard even the very words addressed to myself by Sir George Naylor.' Dr. Wigan thinks he finds a sufficient explanation of this state of mind in the theory of a double brain. 'The persuasion of the same being a repetition,' says he: 'comes on when the attention has been roused by some accidental circumstance, and we become, as the phrase is, wide awake. I believe the explanation to be this: only one brain has been used in the immediately preceding part of the scene: the other brain has been asleep, or in an analogous state nearly approaching it. When the attention of both brains is roused to the topic, there is the same vague consciousness that the ideas have passed through the mind before, which takes place on reperusing the page we had read while thinking on some other subject. The ideas have passed through the brain before: and as there was not sufficient consciousness to fix them in the memory without a renewal, we have no moans of knowing the length of time that had elapsed between the faint impression received by the single brain, and the distinct impression received by the double brain. It may seem to have been many years.' It is a plausible idea: but we have no proof that a single hemisphere of the brain has this distinct action: the analogy of the eyes is against it, for there we never find one eye conscious or active, and the other not. Moreover, this theory does not, as will be seen, explain all the facts: and hence, if for no other reason, it must be set aside. The latest theory on the subject is one started by a person giving the signature 'f in the Notes and Queries (February 14th, 1857). This person thinks that the cases on record are not to be explained otherwise than as cases of foreknowledge. That under certain conditions,' says he: 'the human mind is capable of foreseeing the future, more or less distinctly, is hardly to be questioned. May we not suppose that, in dreams or waking reveries, we sometimes anticipate what will befall us, and that this impression, forgotten in the interval, is revived by the actual occurrence of the event foreseen?' He goes on to remark that in the Confessions of Rousseau there is a remarkable passage which appears to support this theory. This singular man, in his youth, taking a solitary walk, fell into a reverie, in which he clearly foresaw 'the happiest day of his life,' which occurred seven or eight years afterwards. 'I saw myself,' says Jean Jacques: 'as in an ecstasy, transported into that happy time and occasion, where my heart, possessing all the happiness possible, enjoyed it with inexpressible raptures, without thinking of anything sensual. I do not remember being ever thrown into the future with more force, or of an illusion so complete as I then experienced: and that which has struck me most in the recollection of that reverie, now that it has been realized, is to have found objects so exactly as I had imagined them. If ever a dream of man awake had the air of a prophetic vision, that was assuredly such.' Rousseau tells how his reverie was realized at a fete champ flee, in the company of Madame de Warens, at a place which he had not previously seen. 'The condition of mind in which. I found myself, all that we said and did that day, all the objects which struck me, recalled to me a kind of dream which I had at Annecy seven or eight years before, and of which I have given an account in its place. The relations were so striking, that in thinking of them I could not refrain from tears.' remarks that 'if Rousseau, on the second of these occasions, had forgotten the previous one, save a faint remembrance of the ideas which he then conceived, it is evident that this would have been a ease of the kind under consideration.' Mr. Elihu Rich, another correspondent of the useful little periodical above quoted, and who has more than once or twice experienced 'the mysterious sense of having been surrounded at some previous time by precisely the same circumstances, and taken a share in the same conversation,' favours this theory of explanation, and presents us with a curious illustration. 'A gentleman,' says he, 'of high intellectual attainments, now deceased, told me that he had dreamed of being in a strange city, so vividly that he remembered the streets, houses, and public buildings as distinctly as those of any place he ever visited. A few weeks afterwards he was startled by seeing the city of which he had dreamed. The likeness was perfect, except that one additional church appeared in the picture. He was so struck by the circumstance that he spoke to the exhibitor, assuming for the purpose the air of a traveller acquainted with the place. He was informed that the church was a recent erection.' To the same purport is an experience of a remarkable nature winch Mr. John Pavin Phillips, of Haverfordwest, relates as having occurred to himself, in which a second reverie appears to have presented a renewal of a former one: About four years ago,' says he, 'I suffered severely from derangement of the stomach, and upon one occasion, after passing a restless and disturbed night, I came down to breakfast in the morning, experiencing a sense of general discomfort and uneasiness. I was seated at the breakfast-table with some members of my family, when suddenly the room and objects around me vanished away, and I found myself, without surprise, in the street of a foreign city. Never having been abroad, I imagined it to have been a foreign city from the peculiar character of the architecture. The street was very wide, and on either side of the roadway there was a foot pavement elevated above the street to a considerable height. The houses had pointed gables and casemented windows over-hanging the street. The roadway presented a gentle acclivity: and at the end of the street there was a road crossing it at right angles, backed by a green slope, which rose to the eminence of a hill, and was crowned by more houses, over which soared a lofty tower, either of a church or some other ecclesiastical building. As I gazed on the scene before me I was impressed with an overwhelming conviction that I had looked upon it before, and that its features were perfectly familiar to me: I even seemed almost to remember the name of the place, and whilst I was making an effort to do so a crowd of people appeared to be advancing in an orderly manner up the street. As it came nearer it resolved itself into a quaint procession of persons in what we should call fancy dresses, or perhaps more like one of the guild festivals which we read of as being held in some of the old continental cities. As the procession came abreast of the spot where I was standing I mounted on the pavement to let it go by, and as it filed past me, with its banners and gay paraphernalia flashing in the sunlight, the irresistible conviction again came over me that I had seen this same procession before, and in the very street through which it was now passing. Again I almost recollected the name of the concourse and its occasion: but whilst endeavouring to stimulate my memory to perform its function, the effort dispelled the vision, and I found myself, as before, seated at my breakfast-table, cap in hand. My exclamation of astonishment attracted the notice of one of the members of my family, who inquired 'what I had been staring at?' Upon my relating what I have imperfectly described, some surprise was manifested, as the vision, which appeared tome to embrace a period of considerable duration, must have been almost instantaneous. The city, with its landscape, is indelibly fixed in my memory, but the sense of previous familiarity with it has never again been renewed. The 'spirit of man within him 'is indeed a mystery: and those who have witnessed the progress of a case of catalepsy cannot but have been impressed with the conviction that there are dormant faculties belonging to the human mind, which, like the rudimentary wings said to be contained within the skin of the caterpillar, are only to be developed in a higher sphere of being.' In the same work the Rev. Mr. W. L. Nichols, of Bath, adduces a still more remarkable case from a memoir of Mr. William Hone, who, as is well-known, was during the greater part of his life a disbeliever of all but physical facts. He had been worn down to a low condition of vitality by a course of exertion of much the same character as that which gave Scott an experience of the mystic memory. Being called. in the course of business, to a particular part of London, with which he was unacquainted, he had noticed to himself, as he walked along, that ho had never been there before. 'I was shewn,' he says, 'into a room to wait. On looking round, everything appeared perfectly familiar to me: I seemed to recognise every object. I said to myself, 'What is this? I was never here before, and yet I have seen all this: and, if so, there is a very peculiar knot in the shutter.' 'He opened. the shutter, and found the knot! 'Now then,' thought he, 'here is something I cannot explain on my principles: there must be some power beyond matter.' This consideration led Mr. Hone to reflect further on the wonderful relations of man to the Unseen, and the ultimate result was his becoming an earnestly religious man. Mr. Nichols endeavours to shew the case might be explained by Dr. Wigan's theory of a double brain: but it is manifestly beyond that theory to account for the preconception of the knot in the shutter, or the extraneous church in the versioned city. These explanations failing, we are in a manner compelled to think of clairvoyance or the prophetic faculty, because no other explanation is left. On this assumption, an experience of mystic memory might be supposed to arise from a previous dream, or it may be a day reverie, perhaps one of only an instant's duration and very recent occurrence, in which the assemblage of objects and transactions was foreseen:-it appears as the recollection of a more or less forgotten vision. |