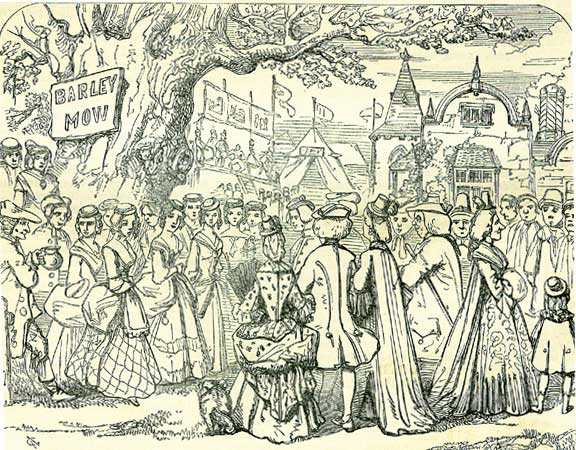

16th MayBorn: Sir William Petty, political economist, 1623, Romsey; Hampshire; Sir Dudley North, merchant, traveller, author of An Account of Turkey, 1641. Died: Pope John XXI, killed at Viterbo, 1277; Samuel Bochard (history and languages), 1667, Caen, Normandy; Paul Rapin de Thoyras, historian, 1725; Dr. Daniel Solander, naturalist, 1782; Jean Baptiste Joseph, Baron Fourier, mathematician, 1830; George Clint, artist, 1854, Kensington; Professor Henslow, botanist, 1861. Feast Day: St. Brendan the Elder, 578; St. Abdjesus, bishop, martyr; St. Abdas, Bishop of Cascar, martyr; St. Ubaldus, Bishop of Gubio; 1160. St. Simon Stock, confessor, of Kent, 1265; St. John Nepomuc, 1383. THE LEGEND OF ST. BRENDANMankind have ever had a peculiar predilection for stories of maritime adventure and discovery, of the mysterious wonders and frightful perils of the mighty ocean; and almost every nation can boast of its one great real or mythical navigator. The Greeks had their Ulysses, the Carthaginians their Hanno. The name of the adventurous Tyrian who first brought back a cargo of gold and peacocks from the distant land of Ophir may be unknown; but every school-boy has read with delight the voyages of the Arabian Sinbad, To come nearer home, as Denmark had its Gorm, and Wales its Madoc, so Ireland had its Brendan. Of all the saintly legends, this of Brendan seems to have been the most popular and widely diffused. It is found in manuscript in all the languages of Western Europe, as well as in the mediaeval Latin of the monkish chroniclers, and several editions of it were printed in the earlier period of typography. Historically speaking, Brendan, an Irishman of royal lineage, was the founder and first abbot of the monastery of Clonfert, in the county of Galway; several treatises on religion and church government, still extant, are attributed to him; and the year 578 is assigned as the date of his death. According to the legend, Brendan, incited by a report he had heard from another abbot, named Berint, determined to make a voyage of discovery, in search of an island supposed to contain the identical paradise of Adam and Eve. So, having procured a good ship, and victualled it for seven years, he was about to start with twelve monks, his selected companions, when two more earnestly entreated that they might be allowed to accompany him. Brendan replied, 'Ye may sail with me, but one of you shall go to perdition ere ye return.' In spite, however, of this warning, the two monks entered the ship. And, forthwith sailing, they were on the morrow out of sight of any land, and, after forty days and forty nights, they saw an island and sailed thitherward, and saw a great rock of stone appear above the water; and three days they sailed about it, ere they could get into the place. But at last they found a little haven, and there they went on land. And then suddenly came a fair hound, and fell down at the feet of St. Brendan, and made him welcome in its manner. Then he told the brethren, 'Be of good cheer, for our Lord hath sent to us this messenger to lead us into some good place.' And the hound brought them to a fair hall, where they found tables spread with good meat and drink. St. Brendan said grace, and he and his brethren sat down, and ate and drank of such as they found. And there were beds ready for them, wherein they took their rest. On the morrow they returned to their ship, and sailed a long time ere they could find any land, till at length they saw a fair island, full of green pasture, wherein were the whitest and greatest sheep ever they saw, for every sheep was as big as an ox. And soon after there came to them a goodly old man, who welcomed them, and said, 'This is the Island of Sheep, and here is never cold weather, but ever summer; and that causes the sheep to be so big and so white.' Then this old man took his leave, and bade them sail forth right east, and, within a short time, they should come into a place, the Paradise of Birds, where they should keep their Easter-tide. And they sailed forth, and came soon after to land, but because of little depth in some places, and in some places great rocks, they went upon an island, weening themselves to be safe, and made thereon a fire to dress their dinner; but St. Brendan abode still in the ship. And when the fire was right hot, and the meat nigh sodden, then this island began to move, whereof the monks were afraid, and fled anon to the ship, and left their fire and meat behind them, and marvelled sore of the moving. And St. Brendan comforted them, and said that it was a great fish named Jascon, which laboured night and day to put its tail in its mouth, but for greatness it could not. The reader will recollect the similar story in the voyages of Sinbad; but Jascon, or Jasconius, as it is styled in the Latin version, turned out to be a much more useful fish than its Eastern counterpart, as will be seen hereafter. After three days' sailing, they saw a fair land full of flowers, herbs, and trees; whereof they thanked God of His good grace, and anon they went on land. And when they had gone some distance they found a well, and thereby stood a tree, full of boughs, and on every bough sat a bird; and they sat so thick on the tree, that not a leaf could be seen, the number of them was so great; and they sang so merrily, that it was a heavenly noise to hear. And then, anon, one of the birds flew from the tree to St. Brendan, and, with flickering of its wings, made a full merry noise like a fiddle, a joyful melody. And then St. Brendan commanded the bird to tell him why they sat so thick on the tree, and sang so merrily. And then the bird said, 'Sometime we were angels in heaven; but when our master Lucifer fell for his high pride, we fell for our offences, some hither and some lower, after the nature of their trespass; and because our trespass is but little, therefore our Lord hath set us here, out of all pain, to serve Him on this tree in the best manner that we can.' The bird, moreover, said to the saint: It is twelve months past that ye departed from your abbey, and in the seventh year hereafter ye shall see the place that ye desire to come to; and all these seven years ye shall keep your Easter here with us every year, and at the end of the seventh year ye shall come to the land of behest! And this was on Easter-day that the bird said these words to St. Brendan. And then all the birds began to sing even-song so merrily, that it was a heavenly noise to hear; and after supper St. Brendan and his fellows went to bed and slept well, and on the morrow rose betimes, and then these birds began matins, prime, And hours, and all such service as Christian men use to sing. Brendan remained with the birds till Trinity Sunday, and then returning to Sheep Island, he took in a supply of provisions, and sailed again into the wide ocean. After many perils, he discovered an island, on which was a monastery of twenty-four monks; with them Brendan spent Christmas, and on Twelfth-day again made sail. On Palm Sunday they reached Sheep Island, and were received by the old man, who brought them to a fair hall, and served them. And on Holy Thursday, after supper, he washed their feet and kissed them, like as our Lord did to His disciples; and there they abode till Easter Saturday evening, and then departed and sailed to the place where the great fish lay; and anon they saw their caldron upon the fish's back, which they had left there twelve months before; and there they kept the service of the Resurrection on the fish's back; and after sailed the same morning to the island where was the tree of birds, and there they dwelt from Easter till Trinity Sunday, as they did the year before, in full great joy and mirth. Thus they sailed, from island to island, for seven years; spending Christmas at the monastery, Palm Sunday at the Sheep Island, Easter-Sunday on the fish's back, and Easter Monday with the birds. There were several episodes, however, in this routine of sailings, of which space can be afforded for one of the strangest only. After having been driven for many days to the northward by a powerful south wind, they saw an island, very dark, and full of stench and smoke; and there they heard great blowing and blasting of bellows, and heard great thunderings, wherefore they were sore afraid, and blessed themselves often. And soon after there came one, all burning in fire, and stared full ghastly on them, of whom the monks were aghast; and at his departure he made the horriblest cry that might be heard. And soon there came a great number of fiends, and assailed them with red hot iron hooks and hammers, in such wise that the sea seemed to be all on fire; but by the will of God, they had no power to hurt them nor the ship. And then they saw a hill all on fire, and a foul smoke and stench coming from thence; and the fire stood on each side of the hill, like a wall all burning. Then one of the monks began to cry and weep full sore, and say that his end was come, and that he might abide no longer in the ship; and anon he leapt into the sea, and then he cried and roared full piteously, cursing the time he was born; 'For now,' said he, 'I must go to perpetual torment.' And then the saying of St. Brendan was verified, what he said to that monk ere he entered the ship. Therefore, it is good a man do penance and forsake sin, for the hour of death is uncertain. According to the Latin version of the legend, the other monk, who voluntarily joined the expedition in defiance of the saint's solemn warning, came to an evil end also. On the first island where they landed, and were so hospitably entertained in 'a fair hall,' the wretched monk, overcome by temptation, stole a silver-mounted bridle and hid it in his vest; and in consequence of the theft died, and was buried on the island. Their last visit to Jascon was marked by a more wonderful occurrence than on any of the previous occasions. So they came to the great fish, where they used to say matins and mass on Easter Sunday. And when the mass was done, the fish began to move, and swam fast in the sea, whereof the monks were sore aghast. But the fish set the monks on land, in the Paradise of Birds, all whole and sound, and then returned to the place it came from. Then St Brendan kept Easter-seated on the hill overlooking the new town, is tide till Trinity Sunday, like as he had done before. The prescribed wandering for seven years having been fulfilled, they were allowed to visit the promised land. After sailing for many days in darkness 'The mist passed away, and they saw the fairest country that a man might see--clear and bright, a heavenly sight to behold. All the trees were loaded with fruit, and the herbage with flowers. It was always day, and temperate, neither hot nor cold; and they saw a river which they durst not cross. Then came a man who welcomed them, saying: Be ye now joyful, for this is the land ye have sought. So lade your ship with fruit, and depart hastily, for ye may no longer abide here. Ye shall return to your own country, and soon after die. And this river that you see here parteth the world asunder, for on that side of the water may no man come that is in this life. Then St. Brendan and his monks took of the fruit, and also great plenty of precious stones, and sailed home into Ireland, where their brethren received them with great joy, giving thanks to God, who had kept them all those seven years from many perils, and at last brought them home in safety. To whom be glory and honour, world without end. Amen.' This legend, absurd as it may appear, exercised considerable influence on geographical science down to a comparatively late period, and formed one of the several collateral causes which led to the discoveries of Columbus. The Spanish government sent out many vessels in search of the Island of St Brendan, the last in 1721. In the treaty of Evord, by which the Portuguese ceded the Canary Islands to the Castillians, the Island of St. Brendan is mentioned as the island which cannot be found. The lower class of Spaniards still relate how Roderick, last of the Goths, made his escape thither; while the Portuguese assert that it served for a retreat to Don Sebastian, after the battle of Acazar. On many old English charts it is to be found under its Irish name of I'Brazil. So common were voyages from Ireland in search of this island during the seventeenth century, that Ludlow, the regicide, when implicated in a conspiracy to seize Dublin Castle, made his escape to the Continent, by chartering a vessel at Limerick under the pretence of seeking for I'Brazil. Leslie of Glasslough, a man of judgment and enterprise, purchased a patent grant of this imaginary island from Charles I, and expended a fortune in seeking for: That Eden, where th' immortal brave Dwell in a land serene, Whose towers beyond the shining wave, At sunset oft are seen. Ah! dream too full of saddening truth! Those mansions o'er the main Are like the hopes I built in youth,- As sunny, and as vain! ST. JOHN NEPOMUCThe fine and venerable old city of Prague, seated on the hill overlooking the new town, is decked out in all its bravery on this day. It is the fete of its favourite saint, the patron saint of Bohemia, St. John Nepomuc. Hundreds, nay thousands, of people flock from the distant hills of the Tyrol, from Hungary, and from all parts of Bohemia, to the celebration. The old bridge dedicated to his memory, and on which his chapel stands, is so crowded that carriages are forbidden to cross it during the twenty-four hours. Service is going forward constantly, and as one party leaves, another fills the edifice. These poor people have walked all the distance, carrying their food, which often consists of cucumber, curds, and bread, in a bundle; they join together in parties, and come singing along the road, so many miles each day. The town presents a most picturesque aspect; the variety of costume worn in Hungary is well known; besides these, we find the loose green shooting-jackets of the Tyrol, the high-pointed hat, and tightly-fitting boots and stockings. The Bohemians, with their blue and red waistcoats, and large hats, remind you of the days of Luther; whilst the women are gay with ribbons tied in their hair, and smartly embroidered aprons. The legend of the saint is, that he lived in the days of a pagan king, whose queen he converted to the true faith, and who privately confessed to St. John. Her husband, hearing of this, demanded to know her confession from the holy man, which he twice refused to reveal, on the plea of duty, though he was under threat of death. The consequence was that the king ordered him to be thrown over the old bridge into the Moldau, first barbarously cutting out his tongue. Tradition generally adds the marvellous to the true, and tells us that five stars shone in a crescent over his head. As a representation of this, a boat always sails between the arches of the bridge towards dusk on the fete day, with five lights, to remind the people of the stars which hung over the dying saint's head. RAPIN AND HIS HISTORYThe huge, voluminous history of England, by Rapin, kept a certain hold on the public favour, even down to a time which the present writer can remember. It was thought to be more impartial than other histories of England, the supposed fact being attributed to the country of the author. But, in reality, Rapin had his twists like other people. A refugee from France under the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, he bore away a sense of wrongs extending back through many Protestant generations of his family, and this feeling expressed itself in a very odd way. In regard to the famous quarrel between Edward III and Philip of Valois, he actually advocates the right of the former, which no Englishman of his own or any later time would have done. Rapin came to England in the expedition of the Prince of Orange, served the new king in Ireland, and afterwards became governor to the son of William's favourite, the Duke of Portland. DR. SOLANDERThe name of Solander, the Swedish botanist, the pupil of Linnaeus, and the friend of Sir Joseph Banks, was honourably distinguished in the progress of natural science in the last century. He was born in Nordland, in Sweden, on the 28th of February, 1736; he studied at Upsala, under Linnnaes, by whose recommendation he came to England in the autumn of 1760, and was employed at the British Museum, to which institution he was attached during the remainder of his life; he died, under-librarian of the Museum, in the year 1782. It was, however, in voyages of discovery that Solander's chief distinction lay, especially in his contributions to botanical knowledge. In 1768, he accompanied Captain Cook in his first voyage round the world; the trustees of the British Museum having promised a continuance of his salary in his absence. During this voyage, Dr. Solander probably saved a large party from destruction in ascending the mountains of Terra del Fuego; and very striking and curious is the story of this adventure in illustrating the effect of drowsiness from cold. It appears that Solander and Sir Joseph Banks had walked a considerable way through swamps, when the weather became suddenly gloomy and cold, fierce blasts of wind driving the snow before it. Finding it impossible to reach the ships before night, they resolved to push on through another swamp into the shelter of a wood, where they might kindle a fire. Dr. Solander, well experienced in the effects of cold, addressed the men, and conjured them not to give way to sleepiness, but, at all costs, to keep in motion. 'Whoever sits down,' said he, 'will sleep; and whoever sleeps, will wake no more.' Thus admonished and alarmed, they set forth once again; but in a little time the cold became so intense as to produce the most oppressive drowsiness. Dr. Solander himself was the first who felt the inclination to sleep too irresistible for him, and he insisted on being suffered to lie down. In vain Banks entreated and remonstrated; down he lay upon the snow, and it was with much difficulty that his friends kept him from sleeping. One of the black servants began to linger in the same manner. When told that if he did not go on, he would inevitably be frozen to death, he answered that he desired nothing more than to lie down and die. Solander declared himself willing to go on, but declared that he must first take some sleep. It was impossible to carry these men; they were therefore both suffered to lie down, and in a few minutes were in a profound sleep. Soon after, some of those men who had been sent forward to kindle a fire, returned with the welcome news that a fire awaited them a quarter of a mile off. Banks then happily succeeded in awaking Solander, who, although he had not been asleep five minutes, had almost lost the use of his limbs, and his flesh was so shrunk that the shoes fell from his feet. He consented to go forward with such assistance as could be given; but no attempts to rouse the black servant were successful, and he, with another black, died there. Dr. Solander returned from this voyage in 1771, laden with treasures, which are still in the collection at the British Museum. He did not receive any remuneration for his perilous services beyond that extended by Sir Joseph Banks. It will be recollected that the spot whereon Captain Cook first landed in Australia was named Botany Bay, from the profusion of plants which the circumnavigators found there, and the actual point of land was named, after one of the naturalists of the expedition, Cape Solander; the discovery has also been commemorated by a brass tablet, with an inscription, inserted in the face of the cliff, by Sir Thomas Brisbane, G.C.B., Governor of New South Wales. PROFESSOR HENSLOWAs Dr. Buckland at Oxford, so Mr. Henslow at Cambridge, did laudable service in leading off the attention of the university from the exclusive study of dead languages and mathematics to the more fruitful and pleasant fields of natural science. John Stevens Henslow was born at Rochester, in 1796, and from a child displayed those tastes which distinguished his whole life. Stories are told of how he made the model of a caterpillar; dragged home a fungus, Lycoperdon giganteum, almost as big as himself; and how, having received as a prize Travels in Africa, his head was almost turned with a desire to become an explorer of that mysterious continent, and make acquaintance with its terrible beasts and reptiles. He went to Cambridge in 1814, where he took high mathematical honours, and in 1825 was appointed Professor of Botany. As Buckland bewitched Oxford with the charms of geology, Henslow did Cambridge with those of botany. All who came within the magic of his enthusiasm caught his spirit, and in his herborizing excursions round Cambridge he drew troops of students in his train. He was an admirable teacher; no one who listened to him could fail to follow and understand. At his lectures he used to provide baskets of the more common plants, such as primroses, and other species easily obtained in their flowering season; and as the pupils entered, each was expected to select a few specimens and bear them to his seat on a wooden plate, so that he might dissect for himself, and accompany the professor in his demonstration. He was also an excellent draughtsman, and by a free use of diagrams he was enabled to remove the last shade of obscurity from his expositions. At his house he held a soiree once a week, to which all were welcomed who had an interest in science. These evenings at the professor's became popular beyond measure, and to this day are held in affectionate remembrance by those who were his guests. In this useful activity, varied by other interests, theological and political, were Henslow's years passed at Cambridge, when in 1837, Lord Melbourne-who had almost given him the bishopric of Norwich-promoted him to the well-endowed rectory of Hitcham, in Norfolk. The people of his parish he found sunk almost to the lowest depth of moral and physical debasement, but Henslow bravely resolved to take them in hand, and spend his strength without reserve in their regeneration. His mode was entirely original. He got up a cricket-club, and encouraged ploughing matches, and all sorts of manly games. He gave every year an exhibition of fireworks on the rectory lawn, and tried to interest the more intelligent of his parishioners in his museum of curiosities. Then he took them annual excursions, sometimes to Ipswich, sometimes to Cambridge, Norwich, the seaside, Kew, and London, leading through these places from one to two hundred rustics at his heels. Then he got up horticultural shows, to which the villagers sent their choice plants; and amid feasting and games he delivered at short intervals what he called 'lecturets' on various matters of morals and economy, brimming over with good sense and good-humour. Of course he paid special attention to his parish school, and from the first he made botany a leading branch of instruction. There were three botanical classes, and admission to the very lowest was denied to any child who could not spell, among other words, the terms Angiospermons, Glumaceons, and Monocotyledons. Under Henslow's enthusiasm and unequalled power of teaching, the hard and difficult vocabulary grew easy to the childhood of Hitcham, and ploughboys and dairymaids learned to discourse in phrases which would perplex a London drawing-room. Whilst looking after the labourers, he did not forget their employers, the farmers; and by lectures to the Hadleigh Farmers' Club he strove to 'convert,' as he expressed it, 'the art of husbandry into the science of agriculture.' In these secular labours Henslow believed that he laid the only durable basis for any spiritual culture that was worth the name. Under his ceaseless energy his parish gradually and surely changed its character from sloth and depravity to industry and virtue; and we scarcely know a more encouraging example of the good a clergyman may effect in the worst environment than that afforded by the story of Henslow's life at Hitcham. The last public appearance of the professor was as president of the natural history section of the British Association at Oxford in June, 1860. In 1861 a complication of disorders, arising, it was thought, from his long habit of overtasking mind and body, brought him to his deathbed. There, in his last hours, was seen the scientific instinct active as ever. In his sufferings he set himself to watch the signs of approaching dissolution, and discussed them with his medical attendants as though they were natural phenomena occurring outside himself. GREENWICH FAIRIn former times, the conception of Whit Monday in the mind of the great mass of Londoners had one central spot of intense brightness in-Greenwich Fair. For some years past, this has been a bygone glory, for magistrates found that the enjoyments of the festival involved much disorder and impropriety; and so its chief attractions were sternly forbidden. Strict justice owns that such an assemblage could not take place without some share of evil consequences; and yet one must sigh to think that so much pleasure, to all appearance purely innocent, has been subtracted from the lot of the industrious classes, and it may even be insinuated that the gain to morality is not entire gain. If Whit Monday dawned brightly, every street in London showed, from an early hour, streams of lads and lasses pouring towards those outlets from the city by which Greenwich (five miles off) was then approached, the Kent Road and the river being the chief. No railway then-no steamers on the river-their place was supplied to some extent by stage-coaches and wherries. When the holiday-maker and his partner had, by whatever means, made their way to Greenwich, they found the principal street filled from end to end with shows, theatrical booths, and stalls for the sale of an infinite variety of merchandise. Usually, however, the first object was to get into the park; a terrible struggle it was, through accesses so much narrower than the multitude required. In this beautiful piece of ground, made venerable by the old oaks of Henry and Elizabeth, and dear to science by the towery Observatory, the youth and maiden-hood of London carried on a series of sports during the whole forenoon. At one place there was kiss-in-the-ring; at another you might, for a penny, enjoy the chance of knocking down half-a-dozen pieces of gingerbread by throwing a stick; but the favourite amusement above all was to run your partner down the well-known slope between the high and low levels of the park. Generally, a row was drawn up at the top, and at a signal off they all set; some bold and successful in getting to the bottom on their feet, others, timid and awkward, tumbling headlong before they were half-way down. The strange disorders of this scene furnished, of course, food for no small merriment; the rule was to take every discomposure and spoiling of dress good-humouredly, Meanwhile there were other regalements. One of the old pensioners of the Hospital would be drawing halfpence for the use of his telescope, whereby you could see St Paul's Cathedral, Barking Church, Epping Forest, or the pirates hanging in chains along the river (the last a favourite spectacle). At another place, a sailor, or one assuming the character, would exemplify the nautical hornpipe to the sounds of a cracked violin. The game of 'thread-my-needle,' played by about a dozen lasses, also had its attractions. After the charms of the park were exhausted, a saunter among the shows and players' booths occupied a few hours satisfactorily. Even the pictures on the exterior, and the musical bands and spangled dancers on the front platform, were no small amusement to minds vacant alike of care and criticism; but to plunge madly in, and see a savage baron get his deserts for along train of cruelties, all executed in a quarter of an hour,-there lay the grand treat of this department. Here, however, there was nothing locally peculiar -nothing but what was to be seen at Bartholomew Fair, or any other fair of importance throughout the country. Towards evening, the dancing booths began to drain off the multitudes from the street. Some of these were boarded structures of two and even three hundred feet long, each, of course, provided with its little band of violinists, each also presenting a bar for refreshments, with rows of seats for spectators. Sixpence was the ordinary price of admission, and for that sum the giddy youth might dance till he was tired, each time with a new partner, selected from the crowd. Here lay the most reprehensible part of the enjoyments of Greenwich Fair, and that which conduced most to bring the festival into disrepute, and cause its suppression. The names adopted for these temples of Terpsichore were often of a whimsical character, as 'The Lads of the Village,' 'The Moonrakers,' 'The Black Boy and Cat,' and so forth. The second of these names probably indicated an Essex origin, with reference to the celebrated fable of the Essex farmers trying to rake Luna out of a pool in which they saw her fair form reflected.  When the limbs were wearied with walking and dancing, the heart satiated with fun, or what passed as such, and perhaps the stomach a little disordered with unwonted meats and drinks, the holiday-makers would address themselves for home. Then did the stage-coaches and the hackneys make rich harvest, seldom taking a passenger to London under four shillings, a tax which but few could pay. The consequence was that vast multitudes set out on foot, and, getting absorbed in public-houses by the way, seldom reached their respective places of abode till an advanced hour of the night. Fairs were originally markets-a sort of commercial rendezvous rendered necessary by the sparseness of population and the paucity of business; and merry-makings and shows were only incidental accompaniments. Now that population is dense, and commercial communications of all kinds are active and easy, the country fair is no longer a necessity, and consequently they have nearly everywhere fallen much off. At one time, the use being obvious and respectable, and the merriments not beyond what the general taste and morality could approve of, the gentlefolk of the manor-house thought it not beneath them to come down into the crowded streets and give their countenance to the festivities. Arm-in-arm would the squire and his dame, and other members of the family, move dignifiedly through the fair, receiving universal homage as a reward for the sympathy they thus showed with the needs and the enjoyments of their inferiors. At the fair of Charlton, in Kent, not much beyond the recollection of living persons, the wife of Sir Thomas Wilson was accustomed to make her appearance with her proper attendants, walking forth from the family mansion into the crowded streets, where she was sure to be hailed with a musical band, got up gratefully in her especial honour. It surely is not in the giving up of such kindly customs that the progress of our age is to be marked. Does it not rather indicate something like a retrogression? This fair of Charlton, which was held on St. Luke's Day (18th of October), had some curious peculiarities. The idea of horns was somehow connected with it in an especial manner. From Deptford and Greenwich came a vast flock of holiday-makers, many of them bearing a pair of horns upon their heads. Every booth in the fair had its horns conspicuous in the front. Ram's horns were an article abundantly presented for sale. Even the gingerbread was marked by a gilt pair of horns. It seemed an inexplicable mystery how horns and Charlton fair had become associated in this manner, till an antiquary at length threw a light upon it by pointing out that a horned ox is the recognised mediaeval symbol of St. Luke, the patron of the fair, fragmentary examples of it being still to be seen in the painted windows of Charlton Church. This fair was one where an unusual license was practised. It was customary for men to come to it in women's clothes-a favourite mode of masquerading two or three hundred years ago-against which the puritan clergy launched many a fulmination. The men also amused themselves, in their way across Blackheath, in lashing the women with furze, it being proverbial that 'all was fair at horn fair.' All over the south of Scotland and north of England there are fairs devoted to the hiring of servants-more particularly farmers' servants -both male and female. In some districts, the servants open to an engagement stand in a row at a certain part of the street, ready to treat with proposing employers; sometimes exhibiting a straw in their mouths, the better to indicate their unengaged condition. It is a position which gives occasion for some coquetry and badinage, and an air of good-humour generally prevails throughout. When the business of the day is pretty well over, the amusement begins. The public houses, and even some of the better sort of hotels, have laid out their largest rooms with long tables and forms, for the entertainment of the multitude. It becomes the recognised duty of the lads to bring in the lasses from the streets, and give them refreshments at these tables. Great heartiness and mirth prevail. Some gallant youths, having done their duty to one damsel, will plunge down into the street, seize another with little ceremony, and bring her in also. A dance in another apartment concludes the day's enjoyments. The writer, in boyhood, has often looked upon these scenes with great amusement; he must now acknowledge that they involve too great an element of coarseness, if not something worse; and he cannot but rejoice to hear that there is now a movement for conducting the periodical business of hiring upon temperance principles. It is one of the misfortunes of the lowly that, bound down to monotonous toil the greater part of their lives, they can scarcely enjoy an occasional day of relaxation or amusement without falling into excesses. Let us hope that in time there will be more frequent and more liberal intervals of relaxation, and consequently less tendency to go beyond reasonable bounds in merry-making. |