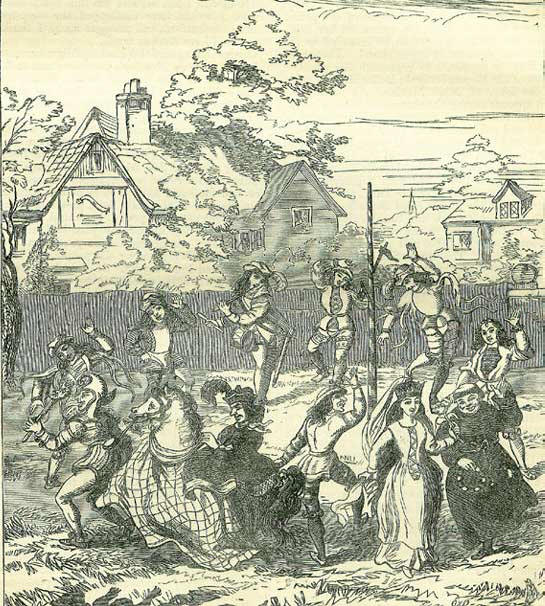

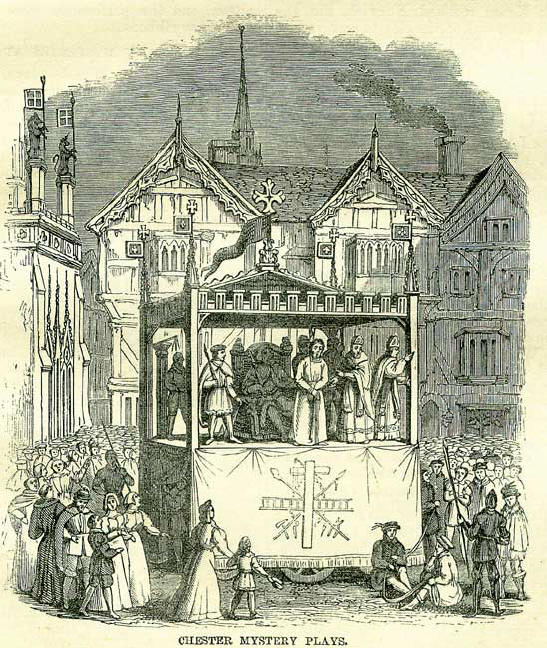

15th MayBorn: Cardinal Alberoni, Spanish minister, 1664, Placentia, Italy; Constantine, Marquis of Normanby, 1797. Died: St. Isidore, 1170, Madrid; Mademoiselle Champmele, celebrated French actress, 1698; Alexander Cunningham, historian, 1737, London; Ephraim Chambers (Cyclopoedia), 1740, London; Alban Butler, author of Lives of the Saints, 1773, St. Omer; Dr. John Wall Callcott, musician, 1821; John Bonnycastle, 1821, Woolwich; Edmund Kean, tragedian, 1833; Daniel O'Connell, 1847. Feast Day: Saints Peter, Andrew, and companions, martyrs, 250. St. Dympna, virgin, martyr, 7th century. St. Genebreed, martyr, 7th century. WHIT SUNDAY (1864)Whit Sunday is a festival of the Church of England, in commemoration of the descent of the Holy Ghost on the Apostles, when 'they were all with one accord in one place,' after the ascension of our Lord; on which occasion they received the gift of tongues, that they might impart the gospel to foreign nations. This event having occurred on the day of Pentecost, Whit Sunday is of course intimately associated with that great Jewish festival. ALBAN BUTLERSupposing any one desired to take a course of reading in what is called hagiology, he might choose between the Acta Sanctorum and Alban Butler's Lives of the Saints. The first would be decidedly an alarming undertaking, for the Acts of the Saints occupy nearly sixty folios. The great work was commenced more than two hundred years ago by Bolland, a Belgian Jesuit. His design was to collect, under each day of the year, the saints' histories associated therewith. He got through January and February in five folios, when he died in 1658. Under the auspices of his successor, Daniel Papebroch, March appeared in 1668, and April in 1675, each in three volumes. Other editors followed bearing the unmelodious names of Peter Bosch, John Stilling, Constantine Suyskhen, Urban Sticken, Cornelius Bye, James Bue, and Ignatius Hubens; and in 1762, one hundred and forty years after the appearance of January, the month of September was completed in eight volumes, making forty-seven in all. A part of October was published, but in its midst the work came to a stand for nearly a century. It was resumed about twenty years ago. Nine volumes for October have now appeared, the last embracing only two days, the 20th and 21st of October, and containing as much matter as the five volumes of Macaulay's History of England. Although abounding in stores of strange, recondite, and interesting information, the Acta Sanctorum do not find many readers outside the walls of convents; and the secular inquirer into saintly history will, with better advantage, resort to Alban Butler's copious, yet manageable narratives. The Rev. Alban Butler, the son of a Northamptonshire gentleman of reduced fortune, was born in 1710, and in his eighth year was sent to the English college at Douay. There he became noted for his studious habits. He did nothing but read; except when sleeping and dressing, a book was never out of his hand. Of those he deemed worthy he drew up abstracts, and filled bulky volumes with choice passages. With a passion for sacred biography, he early began to direct his reading to the collection of materials for his Lives of the Saints. He became Professor of Philosophy, and then of Divinity, at Douay, and in 1745 accompanied the Earl of Shrewsbury and his brothers, the Talbots, on a tour through France and Italy. On his return he was sent to serve as a priest in England, and set his heart on living in London, for the sake of its libraries. To his chagrin he was ordered into Staffordshire. He pleaded that he might be quartered in London for the sake of his work, but was refused, and quietly submitted. Afterwards he was appointed chaplain to the Duke of Norfolk. His Lives of the Saints he published in five quarto volumes, after working on them for thirty years. The manuscript he submitted to Challoner, the vicar apostolic of the London district, who recommended the omission of all the notes, on which. Butler had expended years of research and pains. Like a good Catholic he yielded to the advice, but in the second edition he was allowed to restore them. He was ultimately chosen President of the English college of St. Omer's, where he died in 1773. Of Alban Butler there is nothing more to tell, save that he was a man of a gentle and tolerant temper, and left kindly memories in the hearts of all who knew him. His Lives are written in a simple and readable style; and Gibbon, in his Decline and Fall, perhaps gives the correct Protestant verdict when he says, 'It is a work of merit; the sense and the learning belong to the author-his prejudices are those of his profession.' WhitsuntideThe Pentecost was a Jewish festival, held, as the name denotes, fifty days after the feast of unleavened bread; and its only interest in the history of Christianity arises from the circumstance that it was the day on which the Holy Ghost descended upon the apostles and imparted to them the gift of tongues. It is remarkable that this feast appears to have had no name peculiar to the early languages of Western Europe, for in all these languages its only name, like the German Pfingst, is merely derived from the Greek word, with the exception of our English Whit Sunday, which appears to be of comparatively modern origin, and is said to be derived from some characteristic of the Romish ceremonial on this day. We might suppose, therefore, that the peoples of Western Europe, before their conversion, had no popular religious festival answering to this day. Yet in mediaeval Western Europe, Pentecost was a period of great festivity, and was considered a day of more importance than can be easily explained by the incidents connected with it, recorded in the gospel, or by any later Christian legends attached to it. It was one of the great festivals of the kings and great chieftains in the mediaeval romances. It was that especially on which King Arthur is represented as holding his most splendid court. The sixth chapter of the Mort d'Arthur of Sir Thomas Malory, tells us how, Then King Arthur removed into Wales, and 'let crie a great feast that it should be holden at Pentecost, after the coronation of him at the citie of Carlion.' And chapter one hundred and eighteen adds, 'So King Arthur had ever a custome, that at the high feast of Pentecost especially, afore al other high feasts in the yeare, he would not goe that day to meat until he had heard or seene some great adventure or mervaile. And for that custom all manner of strange adventures came before King Arthur at that feast afore all other feasts.' It was in Arthur's grand cour pleniere at the feast of Pentecost, that the fatal mantle was brought which threw disgrace on so many of the fair ladies of his court. More substantial monarchs than Arthur held Pentecost as one of the grand festivals of the year; and it was always looked upon as the special season of chivalrous adventure of tilt and tournament. In the romance of Bevis of Hampton, Pentecost, or, as it is there termed, Whitsuntide, appears again as the season of festivities In somer at Whitsontyde, Whan knightes most on horsebacke ride, A tours let they make on a day e, Steedes and palfraye for to assaye, Whiche horse that best may ren We seem justified from these circumstances in supposing that the Christian Pentecost had been identified with one of the great summer festivals of the pagan inhabitants of Western Europe. And this is rendered more probable by the circumstance, that our Whitsuntide still is, and always has been, one of the most popularly festive periods of the year. It was commonly celebrated in all parts of the country by what was termed the Whitsun-ale, and it was the great time for the morris-dancers. In Douce's time, that is, sixty or seventy years ago, a Whitsun-ale was conducted in the following manner: Two persons are chosen, previously to the meeting, to be lord and lady of the ale, who dress as suitably as they can to the characters they assume. A large empty barn, or some such building, is provided for the lord's hall, and fitted up with seats to accommodate the company. Here they assemble to dance and regale in the best manner their circumstances and the place will afford; and each young fellow treats his girl with a riband or favour. The lord and lady honour the hall with their presence, attended by the steward, sword-bearer, purse-bearer, and mace-bearer, with their several badges or ensigns of office. They have likewise a train-bearer or page, and a fool or jester, drest in a party-coloured jacket, whose ribaldry and gesticulation contribute not a little to the entertainment of some part of the company. The lord's music, consisting of a pipe and tabor, is employed to conduct the dance. These festivities were carried on in a much more splendid manner in former times, and they were considered of so much importance, that the expenses were defrayed by the parish, and charged in the churchwardens' accounts. Those of St. Mary's, at Reading, as quoted in Coates's History of that town, contain various entries on this subject, among which we have, in 1557: 'Item payed to the morrys daunsers and the mynstrelles, mete and drink at Whytsontide, iijs. iiijd.' The churchwardens' accounts at Brentford, in the county of Middlesex, also contain many curious entries relating to the annual Whitsun-ales in the seventeenth century; and we learn from them, as quoted by Lysons, that in 1621 there was 'Paid to her that was lady at Whitsontide, by consent, 5s.' Various games were indulged in on these occasions, some of them peculiar to the season, and archery especially was much practised. The money gained from these games seems to have been considered as belonging properly to the parish, and it is usually accounted for in the church-wardens' books, among the receipts, as so much profit for the advantage of the parish, and of the poor. THE MORRIS-DANCEAntiquaries seem agreed that the old English morris-dance, so great a favourite in this country in the sixteenth century, was derived through Spain from the Moors, and that its name, in Spanish Morisco, a Moor, was taken from this circumstance. It has been supposed to be originally identified with the fandango. It was certainly popular in France as early as the fifteenth century, under the name of Morisque, which is an intermediate step between the Spanish Morisco and the English Morris. We are not aware of any mention of this dance in English writers or records before the sixteenth century; but then, and especially in writers of the Shakspearian age, the allusions to it become very numerous. It was probably introduced into this country by dancers both from Spain and France, for in the earlier allusions to it in English it is sometimes called the Morisco, and sometimes the Morisce or Morisk. Here, however, it seems to have been very soon united with an older pageant dance, performed at certain periods in honour of Robin Hood and his out-laws, and thus a morris-dance consisted of a certain number of characters, limited at one time to five, but varying considerably at different periods.  The earliest allusions to the morris-dance and its characters were found by Mr. Lysons in the churchwardens' and chamberlains' books at Kingston-upon-Thames, and range through the last two years of the reign of Henry VII and the greater part of that of his successor, Henry VIII. We learn there that the two principal characters in the dance represented Robin Hood and Maid Marian; and the various expenses connected with their different articles of dress, show that they were decked out very gaily. There was also a frere, or friar; a musician, who is sometimes called a minstrel, sometimes a piper, and at others a taborer,-in fact he was a performer on the pipe and tabor, and a 'dysard' or fool. The churchwardens accounts of St. Mary's, Reading, for 1557, add to these characters that of the hobby-horse. Item, payed to the mynstrels and the hobby-horse uppon May-day, 3s. Payments to the morris-dancers are again recorded on the Sunday after May-day, and at Whitsuntide. The dancers, perhaps, at first represented Moors-prototypes of the Ethiopian minstrels of the present day, or at least there was one Moor among them; and small bells, usually attached to their legs, were indispensable to them. In the Kingston accounts of the 29th of Henry VIII (1537-8), the wardrobe of the morris-dancers, then in the custody of the church-wardens, is thus enumerated: A fryers cote of russet, and a kyrtele weltyd with red cloth, a Mowrens (Moor's) cote of buckram, and four morres daunsars cotes of white fustian spangelid, and too gryne saten cotes, and disarddes cote of cotton, and six payre of garters with belles. There was preserved in an ancient mansion at Betley, in Staffordshire, some years ago, and we suppose that it exists there still, a painted glass window of apparently the reign of Henry VIII, representing in its different compartments the several characters of the morris-dance. George Tollett, Esq., who possessed the mansion at the beginning of this century, and who was a friend of the Shakspearian critic, Malone, gave a rather lengthy dissertation on this window, with an engraving, in the variorum edition of the works of Shakspeare. Maid Marian, the queen of May, is there dressed in a rich costume of the period referred to, with a golden crown on her head, and a red pink, supposed to be intended as the emblem of summer, in her left hand. This queen of May is supposed to represent the goddess Flora of the Roman festival; Robin Hood appears as the lover of Maid Marian. An ecclesiastic also appears among the characters in the window, 'in the full clerical tonsure, with a chaplet of white and red beads in his right hand, his corded girdle and his russet habit denoting him to be of the Franciscan order, or one of the Grey Friars; his stockings are red; his red girdle is ornamented with a golden twist, and with a golden tassel.' This is supposed to be Friar Tuck, a well-known character of the Robin Hood Ballads. The fool, with his cock's comb and bauble, also takes his place in the figures in the window; nor are the tabourer, with his tabor and pipe, or the hobby-horse wanting. The illustration on the preceding page throws these various characters into a group representing, it is conceived, a general morrisdance, for which, however, fewer performers might ordinarily serve. The morris-dance of the individual, with an occasional Maid Marian, seems latterly to have been more common. One of the most remarkable of these was performed by William Kemp, a celebrated comic actor of the reign of Elizabeth, being a sort of dancing journey from London to Norwich. This feat created so great a sensation, that he was induced to print an account of it, which was dedicated to one of Elizabeth's maids of honour. The pamphlet is entitled, 'Kemp's Nine Daies' Wonder, performed in a daunce from London to Norwich. Containing the pleasure, paines, and kinde entertainment of William Kemp betweene London and that Citty, in his late Morrice.' It was printed in 1600; and the title-page is adorned with a woodcut, representing Kemp dancing, and his attendant, Tom the Piper, playing on the pipe and tabor. The exploit took place in 1599, but it was a subject of popular allusion for many years afterwards. Kemp started from London at seven in the morning, on the first Monday in Lent, and, after various adventures, reached Romford that night, where he rested during Tuesday and Wednesday. He started again on Thursday morning, and made an unfortunate beginning by straining his hip; but he continued his progress, attended by a great number of spectators, and on Saturday morning reached Chelmsford, where the crowd assembled to receive him was so great, that it took him an hour to make his way through them to his lodgings. At this town, where Kemp remained till Monday, an incident occurred which curiously illustrates the popular taste for the morris-dance at that time. At Chelmsford, a mayde not passing foureteene years of age, dwelling with one Sudley, my kinde friend, made request to her master and dame, that she might daunce the Morrice with me in a great large roome. They being intreated, I was soone wonne to fit her with bels; besides, she would have the olde fashion, with napking on her armes; and to our jumps we fell. A whole houre she held out; but then being ready to lye downe, I left her off; but thus much in her praise, I would have challenged the strongest man in Chelmsford, and amongst many I thinke few would have done so much. Other challenges of this kind, equally unsuccessful, took place on Monday's progress; and on the Wednesday of the second week, which was Kemp's fifth day of labour,-in which he danced from Braintree, through Sudbury, to Melford,-he relates the following incidents. In this towne of Sudbury there came a lusty, tall fellow, a butcher by his profession, that would in a Morrice keepe me company to Bury. I being glad of his friendly offer, gave him thankes, and forward wee did set; but ere ever wee had measur'd halfe a mile of our way, he gave me over in the plain field, protesting, that if he might get a 100 pound, he would not hold out with me; for, indeed, my pace in dancing is not ordinary. As he and I were parting, a lusty country lasse being among the people, cal'd him faint-hearted lout, saying, 'If I had begun to daunce, I would have held out one myle, though it had cost my life.' At which words many laughed. 'Nay,' saith she, ' if the dauncer will lend me a leash of his belles, I'le venter to treade one myle with him myselfe.' I lookt upon her, saw mirth in her eies, heard boldness in her words, and beheld her ready to tucke up her russat petticoate; I fitted her with bels, which she merrily taking, garnisht her thicke short legs, and with a smooth brow bad the tabrer begin. The drum strucke; forward marcht I with my merry Mayde Marian, who shooke her fat sides, and footed it merrily to Melford, being a long myle. There parting with her (besides her skinfull of drinke), and English crowne to buy more drinke; for, good wench, she was in a pittious heate; my kindness she requited with dropping some dozen of short courtsies, and bidding Godblesse the dauncer. I bade her adieu; and, to give her her due, she had a good care, daunst truly, and wee parted friends. Having been the guest of 'Master Colts,' of Melford, from Wednesday night to Saturday morning, Kemp made on this day another day's progress. Many gentlemen of the place accompanied him the first mile, 'Which myle,' says he: Master Colts his foole would needs daunce with me, and had his desire, where leaving me, two fooles parted faire in a foule way; I keeping on my course to Clare, where I a while rested, and then cheerefully set forward to Bury.' He reached Bury that evening, and was shut up there by an unexpected accident, so heavy a fall of snow, that he was unable to continue his progress until the Friday following. This Friday of the third week since he left London was only his seventh day's dancing; and he had so well reposed that he performed the ten miles from Bury to Thetford in three hours, arriving at the latter town a little after ten in the forenoon. 'But, indeed, considering how I had been booted the other journeys before, and that all this way, or the most of it, was over a heath, it was no great wonder; for I far'd like one that had escaped the stockes, and tride the use of his legs to out-run the constable; so light was my heeles, that I counted the ten myle as a leap. At Thetford, he was hospitably entertained by Sir Edwin Rich, from Friday evening to Monday morning; and this worthy knight, 'to' conclude liberally as hee had begun and continued, at my departure on Monday, his worship gave me five pounds,' a considerable sum at that time. On Monday, Kemp danced to Hingham, through very bad roads, and frequently interrupted by the hospitality or importunity of the people on the road. On Wednesday of the fourth week Kemp reached Norwich, but the crowd which came out of the city to receive him was so great, that, tired as he was, he resolved not to dance into it that day; and he rode on horseback into the city, where he was received in a very flattering manner by the mayor, Master Roger Weld. It was not till Saturday that Kemp's dance into Norwich took place, his journey from London having thus taken exactly four weeks, of which period nine days were occupied in dancing the Morris. The morris-dance was so popular in the time of James I, that when a Dutch painter of that period, Vinekenboom, executed a painting of Richmond palace, he introduced a morris-dance in the foreground of the picture. In Horace Walpole's time, this painting belonged to Lord Fitzwilliam; and Douce, in his dissertation on the morris-dance, appended to the 'Illustrations of Shakspeare,' has engraved some of the figures. At this time the favourite season of the morrisdance was Whitsuntide. In the well-known passage of the play of Henry V, the Dauphin of France is made to twit the English with their love of these performances. When urging to make preparations against the English, he says And let us do it with no show of fear; No! with no more than if we heard that England Were busied with a Whitson morris-dance. In another play (All's Well that Ends Well, act ii., se. 2), Shakspeare speaks of the fitness of ' a morris for May-day;' and it formed a not unimportant part of the observances on that occasion. A tract of the time of Charles I., entitled Mythomistes, speaks of ' the best taught country morrisdancer, with all his bells and napkins,' as being sometimes employed at Christmas; so that the performance appears not to have been absolutely limited to any period of the year, though it seems to have been considered as most appropriate to Whitsuntide and the month of May. The natives of Herefordshire were celebrated for their morris-dancers, and it was also a county remarkable for longevity. A pamphlet, printed in the reign of James I., commemorates a party of Herefordshire morris-dancers, ten in number, whose ages together amounted to twelve hundred years. This was probably somewhat exaggerated; but, at a later period, the names of a party of eight morris-dancers of that county are given, the youngest of whom was seventy-nine years old, while the age of the others ranged from ninety-five to a hundred and nine, making together just eight hundred years. Morris-dancing was not uncommon in Herefordshire in the earlier part of the present century. It has been practised during the same period in Gloucestershire and Somerset, in Wiltshire, and in most of the counties round the metropolis. Hone saw a troop of Hertfordshire morrisdancers performing in Goswell-street Road, London, in 1826. Mrs. Baker, in her Glossary of Northamptonshire Words, published in 1854, speaks of them as still met with in that county. And Halliwell, in his Dictionary of Archaic and Provincial Words, also speaks of the morrisdance as still commonly practised in Oxford-shire, though the old costume had been forgotten, and the performers were only dressed with a few ribbons. THE WHITSUN MYSTERIES AT CHESTERThe mystery or miracle plays, of which we read so much in old chronicles, possess an interest in the present day, not only as affording details of the life and amusements of the people in the middle ages-of which we have no very clear record but in them and the illuminated MSS.-but also in helping us to trace the progress of the drama from a very early period to the time when it reached its meridian glory in our immortal Shakspeare. It is said that the first of these plays, one on the passion of our Lord, was written by Gregory of Nazianzen, and a German nun of the name of Roswitha, who lived in the tenth century, and wrote six Latin dramas on the stories of saints and martyrs. When they became more common, about the eleventh or twelfth century, we find that the monks were generally not only the authors, but the actors. In the dark ages, when the Bible was an interdicted book, these amusements were devised to instruct the people in the Old and New Testament narratives, and the lives of the saints; the former bearing the title of mysteries, the latter of miracle plays. Their value was a much disputed point among churchmen: some of the older councils forbade them as a profane treatment of sacred subjects; Wickliffe and his followers were loud in condemnation; yet Luther gave them his sanction, saying, 'Such spectacles often do more good, and produce more impression, than sermons.' In Sweden and Denmark, the Lutheran ecclesiastics followed the example of their forefathers, and wrote and encouraged them to the end of the seventeenth century; it was about the middle of that century when they ceased in England. Relics of them may still be traced in the Cornish acting of 'St George and the Dragon,' and 'Beelzebub.' They were usually performed in churches, but frequently in the open air, in cemeteries, market-places, and squares, being got up at a cost much exceeding the spectacles of the modern stage. We read of one at Palermo which cost 12,000 ducats for each performance, and comprised the entire story of the Bible, from the Creation to the Incarnation; another, of the Crucifixion, at the pretty little town of Aci Reale, attracted such crowds that all Sicily was said to congregate there. The stage was a lofty and large platform before the cathedral, whilst the senate-house served as a side scene, from which issued the various processions. The mixture of sacred and profane persons is really shocking: the Creator with His angels occupied the highest stage, of which there were three; the saints the next; the actors the lowest; on one side of this was the mouth of hell, a dark cavern, out of which came fire and smoke, and the cries of the lost; the buffoonery and coarse jests of the devils who issued from it formed the chief attraction to the crowd, and were considered the best part of the entertainment. Sometimes it was productive of real danger, setting fire to the whole stage, and producing the most tragic consequences; as at Florence, where numbers lost their lives. Some of the accounts of these stage properties, in Mr. Sharp's extracts, are amusing to read: Item, payd for mendyng hell mought, 2d.'-' Item, payd for kepyng of fyer at hell mothe, 4d.'-' Payd for settyng the world of fyer, 5d. We seem to have borrowed our plays chiefly from the French; there is indeed a great similarity between them and the Chester plays; but the play of wit is greater in the former than the latter, each partaking of the character of the nation. At first they were written in Latin, when of course the acting was all that the people understood: that, however, was sufficient to excite them to great hilarity; afterwards they seem to have been composed for the neighbour-hood in which they were performed. We have no very authentic account of the year when the mysteries were first played at Chester; some fix it about 1268, which is perhaps too early. In a note to one of the proclamations, we are told that they were written by a monk of Chester Abbey, Randall Higgenett, and played in 1327, on Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday in Whitsun week. They were always acted in the open air, and consisted of twenty-four parts, guilds of the city; the tanners beginning with each part or pageant being taken by one of the 'The Fall of Lucifer;' the drapers took the guilds of the city; the tanners beginning with 'The Fall of Lucipher;' the drapers took the 'Creation;' the water-carriers of the Dee suit-ably enough acted 'The Flood,' and so on; the first nine being performed on Monday, the nine following on Tuesday, and the remaining seven on Wednesday.  Twenty-four large scaffolds or stages were made, consisting of two tiers, or rowmes' as they are called, and fixed upon four wheels: in the lower one the actors dressed and undressed; the upper one, which was open on all sides for the spectators to see distinctly, was used for acting. By an excellent arrangement, to prevent crowding, each play was performed in every principal street; the first began before the old abbey gates, and when finished it was wheeled on to the market-cross, which was the mayor's position in all shows; by the time it was ended, the second pageant was ready to take its place, and it moved forward to Water-gate, and then to Bridge Street, so that all the pageants were going on at different places at the same time. Great order was preserved, in spite of the immense concourse of people who came from all quarters to enjoy the spectacle; and scaffolds were put up in all the streets, on which they might sit, for which privilege it is supposed that payment was received. It was wisely ordered that no man should wear any weapon within the precincts of the city during the time of the plays, as a further inducement, were any wanting, to make the people congregate to hear the 'holsome doctrine and devotion' taught by them. Pope Clement granted to each person attending a thousand days' pardon, and the Bishop of Chester forty days of the same grace. They were introduced by 'banes', or proclamation, a word which is still retained in our marriage bans; three heralds made it with the sound of trumpets, and set forth in a lengthy prologue the various parts which were to be shown. ' The Fall of Lucifer' was a very popular legend from the earliest ages of Christianity, and its influence is felt to the present day, having been the original groundwork upon which Milton wrote some of his finest passages in Paradise Lost, which, as is well known, was intended to be a sacred drama commencing with Satan's address to the sun. Pride is represented as the cause of his fall; he declares, ' that all heaven shines through his brightness, for God hymselfe shines not so cleare;' and, on attempting to seat himself on the throne of God, he is cast down with Light-born, and part of the nine orders of angels, among whom there follows a scene of bitter repentance and recrimination that they ever listened to the tempter. The stage directions for these scenes are curious enough; a great tempest is to spout forth fire, and a secret way underneath is to hide the evil angels from the spectators' sight. It is unnecessary to describe each of these plays, as for the most part they follow the Bible narrative very closely; but, in passing, we will notice a few of the legends and peculiarities mixed up with them. Thus a very popular part was that of Noah's wife, who preferred staying with her gossips to entering the ark; and, with the characteristic perverseness of woman, had to be dragged into it by her son Shem, when she gives her husband a box on the ear. The play of the' Shepherds of Bethlehem' gives some curious particulars of country life. The three shepherds meet and converse about their flocks, and then propose that each should bring out the food he has with him, and make a pic-nic of the whole. A wrestling match follows, and then the angels appear, and they go to Bethlehem; their gifts are curious, the first says Heale kinge! borne in a mayden's bower, Proffites did tell thou shouldest be our succore. Loe, I bring thee a bell; I praie thee save me from hell, So that I maye with thee dwell, And serve thee for aye. The next Heale thee, blessed full borne (child), Loe, sonne, I bring thee a flaggette, Theirby heinges a spoune, To eate thy pottage with all at noune. The last Loe, sonne, I bring thee a cape, For I have nothinge elles. Their boys follow with offerings: one 'a payre of ould hose;' another, 'a fayre bottill;' 'a pipe to make the woode ringe;' and lastly, 'a nutthooke to pull down aples, peares, and plumes, that oulde Joseph nede not hurte his thombes.' In the 'Passion,' the 'Tourmentoures' are very prominent, with their coarse rough jokes and rude buffetings.' The Harrowing of Hell,' is a very singular part. Christ is represented as descending there, and choosing out Adam, Seth, Isaiah, and many other saints to go to Paradise, where they are met by Enoch and Elijah, who until this period had been its solitary inmates. There is in this piece a strong satire against a woman who is left behind; she says: Wo be to the tyme when I came heare. Some tyme I was a taverner, A gentill gossipe and a tapstere, Ofwyne and ale a trustie brewer, Which wo hath me wroughte: Of cannes I kept no trewe measuer, My cuppes I soulde at my pleasure, Deceavinge manye a creature. With hoppes I made my ale stronge, Ashes and erbes I blend among, And marred so good mm-the; Therefore I may my handes wringe, Shake my cannes, and cuppes ringe; Sorrowful may I siche and singe That ever I so dealt. These allusions to the taverners are so frequent in this description of writing, that we may feel sure they were guilty of much evil doing. The play of 'Ezekiel' contains a summary of various prophecies, and especially the fifteen signs which were to precede the end of the world, a subject which then much engrossed the thoughts of mankind. The signs, as fixed by St. Jerome, were as follow:-The first day the sea was to rise as a wall higher than the hills; the second, to disappear entirely; on the third, great fishes were to rise from it, and 'yore hideously;' the fourth, the sea and all waters were to be on fire; the fifth, a bloody dew was to fall on all trees and herbs; on the sixth, churches, cities, and houses were to be thrown down; the seventh, the rocks were to be rent; the eighth, an earthquake; on the ninth, the hills and valleys were to be made plain; on the tenth, men who had hidden themselves in the caves were to come out mad; the eleventh, the dead should arise; the twelfth, the stars were to fall; the thirteenth, all men should die and rise again; on the fourteenth, earth and heaven should perish by fire; and the fifteenth would see the birth of the new heaven and new earth. 'Antichrist' the subject of the next play, was also a much expected character in the middle ages. He performs the miracle of self-resurrection, to deceive the kings who ask for proofs of his power; and brings all men to worship and sacrifice to him. Enoch and Elijah come from Paradise to expose their sin, and, after a long disputation, are martyred, Michael the archangel coming at the same moment and killing Antichrist, who is carried off by two demons; the martyrs rising and ascending with Michael. 'Doomsday' forms the last of the series, in which a pope, emperor, king, and queen are judged and saved; while a similar series confess their various sins, and are turned into hell. The queen says: Fie on pearls! fie on pride! Fye on gowne! fye on hyde! (skin) Fye on hewe! fye on gayde! (gold) Thes harrowe me to hell. Jesus descends with his angels, and complains of the injuries men have done to him: how his members bled afresh at every oath they swore, and that he had suffered more from them than from his Jewish persecutors. There can be no doubt that the people of the most 'ancient, renowned citie of Caerleon, now named Chester,' were passionately fond of these ' Shewes;' and when the progress of enlightenment and refinement which the Reformation brought about banished the mystery plays, as bordering on profanity and licentiousness, as well as having a strong flavour of popery about them, they set about with alacrity to substitute in their place the pageants which became so general in the reigns of the Tudors and Stuarts, and are connected in history with the journeys or progresses of these monarchs. These pageants or triumphs have, like their predecessors, the mysteries, their relation to the English drama; not only were they composed for the purpose of flattering and complimenting their princes, but a moral end was constantly kept in view: virtue was applauded, while vice was set forth in its most revolting and unpleasing colours; and the altercations between these two leading personages often afforded the populace the highest amusement. The opportunity was also seized upon of presenting to royal ears some of the political abuses of the day; as in one offered by the Inns of Court to Charles the First, where ridicule was thrown upon the vexatious law of patents: a fellow appearing with a bunch of carrots on his head, and a capon on his fist, and asking for a patent of monopoly as the first inventor of the art of feeding capons with carrots, and that none but himself should have privilege of the said invention for fourteen years; whilst another came mounted on a little horse with an immense bit in his mouth, and the request that none should be allowed to ride unless they purchased his bits. Considerable sums of money were spent on these pageants; the expense falling sometimes on the guilds, who each took their separate part in the performance, or the mayor of the city would frequently give one at his own cost; whilst the various theatrical properties would seem to have been kept in order from the city funds, as we often read such entries as these in their books: 'For the annual painting of the city's four giants, one unicorn, one dromedarye, one luce, one asse, one dragon, six hobby-horses, and sixteen naked boys.' -'For painting the beasts and hobby-horses, forty-three shillings. For making new the dragon, five shillings; and for six naked boys to beat at it, six shillings.' The first of these pageants of which we have any record as performed at Chester, was in 1529; the title was 'Kynge Robart of Cicyle.' 'The History of Aeneas and Queen Dido' was played on the Rood-eye in 1563, on the Sunday after Midsummer-day, during the time of the yearly fair, which attracted buyers and sellers in great numbers from Wales and the neighbouring counties. Earl Derby, Lord Strange, and other noblemen honoured these representations with their presence. The pageant which we are about to describe, and which is the only one preserved to the present day, was given by Mr. Robert Amory, sheriff of Chester in 1608, a liberal and public-spirited man, who benefited his city in many ways. It was got up in honour of Henry Frederic, the eldest son of James the First, on his creation as Prince of Wales; and perhaps no prince who ever lived was more worthy of the festival. The author addresses his readers with a certain amount of self-approbation; he says: To be brief, what was done was so done, as being by the approbation of many said to bee well done; then, I doubt not, but it may merit the mercifull construction of some few who may chance to sweare 'twas most excellently ill done. Zeale procured it, lone deuis'd (devised) it, boyes per-formed it, men beheld it, and none but fooles dispraised it. As for the further discription of the businesse I referre to further relation; onely thus: The chiefest part of this people-pleasing spectacle consisted in three Bees, viz., Boyes, Beasts, and Bels: Bels of a strange amplitude and extraordinarie proportion; Beasts of an excellent shape and most admirable swiftnesse; and Boyes of a rare spirit and exquisite performance. These wonderful beasts consisted of two personages who took a leading part in all pageants, and were the 'greene or salvage men;' they were sometimes clothed completely in skins, but on this occasion ivy leaves were sewed on to an embroidered dress, and garlands of the same leaves round their heads; a 'huge blacke shaggie hayre' hung over their shoulders, whilst the 'herculean clubbes' in their hands made them fit and proper to precede and clear the way for the procession that followed. With them came the highly popular and important artificial dragon, 'very lively to behold: pursuing the savages, entring their denne, casting fire from his mouth; which afterwards was slaine, to the great pleasure of the spectators, bleeding, fainting, and staggering as though he endured a feelinge paine even at the last gaspe and farewell.' The various persons who were to take part in the procession met at the old 'Highe Crosse,' which stood at the intersection of the four principal streets in Chester, and the proceedings were opened by a man in a grotesque dress climbing to the top of it, and fixing upon a bar of iron an 'Ancient,' or flag of the colours of St. George; at the same time he called the attention of all present by beating a drum, firing off a gun, and brandishing a sword, after which warlike demonstrations he closed his exhibition by standing on his head with his feet in the air, on the bar of iron, 'very dangerously and wonderfully, to the view of the beholders, and casting fireworks very delightfull.' Envy was there on horseback, with a wreath of snakes about her head and one in her hand; Plenty came garlanded with wheat ears round her body, strewing wheat among the multitude as she rode along; St. George, in full armour, attended by his squires and drummers, made a glorious show; Fame (with her trumpet), Peace, Joy, and Rumour were in their several places, spouting their orations; whilst Mercury, descending from heaven in a cloud, artificially winged, 'a wheele of fire burning very cunningly, with other fire-works,' mounted the Cross by the assistance of ropes, in the midst of heavenly melody. Other horsemen represented the City of Chester, the King, and the Prince of Wales, carrying the suitable colours, shields and escutcheons emblazoned on their dresses and horses' foreheads. The three silver gilt bells, which were to be run for, supported by lions rampant, were carried with many trumpets sounding before; and, when all were marshalled, eight voices sang the opening strain: Come downe, thou mighty messenger of blisse, Come, we implore thee; Let not thy glory be obscured from us, Who most adore thee. Then come, oh come, great Spirit, That we may joyful sing, Welcome, oh welcome to earth, Joy's dearest darling. Lighten the eyes, thou great Mercurian Prince, Of all that view thee, That by the lustre of their optick sense They may pursue thee: Whilst with their voyces Thy praise they shall sing, Come away, Joy's dearest darling. Mercury replies to this invocation, and then follow a series of most tedious speeches from each allegorical person, in praise of Britain in general, and Prince Henry in particular, with which we should be sorry to weary our readers. Envy comes in at the end, to sneer at the whole and spoil the sport; and in no measured terms explains the joy she feels, To see a city burnt, or barnes on fire, To see a sonne the butcher of his sire; To see two swaggerers eagerly to strive Which of them both shall make the hangman thrive; To see a good man poore, or wise man hare, To see Dame Virtue overwhelmed with care; To see a ruined church, a preacher dumbe,' &c. But Joy puts her to flight, saying, 'Envy, avaunt! thou art no fit compeere T' associate with these our sweet consociats here; Joy doth exclude thee,' &c. Thus ends the pageant of 'Chester's Triumph in Honour of her Prince:' what followed cannot be better described than in the words of the author, one Richard Davies, a poet unknown to fame. 'Whereupon all departed for a while to a place upon the river, called the Roode, garded with one hundred and twentie halberders and a hundred and twentie shotte, bravely furnished. The Mayor, Sheriffs, and Aldermen of Chester, arrayed in their scarlet, having seen the said shewes, to grace the same, accompanied, and followed the actors unto the said Roode, where the ships, barques, and pinises, with other vessels harbouring within the river, displaying the armes of St. George upon their maine toppes, with several pendents hanging thereunto, discharged many voleyes of shotte in honour of the day. The bels, dedicated, being presented to the Mayor. Proclamation being generally made to bring in horses to runne for the said bels, there was runne a double race, to the greate pleasure and delight of the spectators. Men of greate worthe running also at the ring for the saide cuppe, dedicated to St. George, and those that wonne the prizes had the same, with the honour thereto belonging. The said several prizes, being with speeches and several wreathes set on their heads, delivered in ceremonious and triumphant manner, after the order of the Olympian sportes, whereof these were an imitation.' THE WHITSUN-ALEAle was so prevalent a drink amongst us in old times, as to become a part of the name of various festal meetings, as Leet-ale, Lamb-ale, Bride-ale [bridal], and, as we see, Whitsun-ale. It was the custom of our simple ancestors to have parochial meetings every Whitsuntide, under the auspices of the churchwardens, usually in some barn near the church, all agreeing to be good friends for once in the year, and spend the day in a sober joy. The squire and lady came with their piper and taborer; the young danced or played at bowls; the old looked on, sipping their ale from time to time. It was a kind of pic-nic, for each parishioner brought what victuals he could spare. The ale, which had been brewed pretty strong for the occasion, was sold by the churchwardens, and from its profits a fund arose for the repair of the church. In latter days, the festival degenerated, as has been the case with most of such old observances; but in the old times there was a reverence about it which kept it pure. Shakspeare gives us some idea of this when he adverts to the song in Pericles It hath been snug at festivals, On ember eves, and holy ales WHIT SUNDAY FETE AT NAPLESAmong the religious festivals of the Neapolitans none is more joyously kept than that of the Festa di Monte Vergine, which takes place on Whit Sunday, but usually lasts three days. The centre of attraction is a church situated on a mountain near Avelino, and as this is a day's journey from Naples, carriages are in requisition. The remarkable feature of the festival is the gaiety of the crowds who attend from a wide district around. In returning home, the vehicles. of all sorts whichhave been pressed into the service are decorated in a fantastic manner with flowers and boughs of trees; the animals which draw the carriages, consisting sometimes of a bullock and ass, as represented in the subjoined cut, are ornamented with ribbons; and numbers of the merry-makers, bearing sticks, with flowers and pictures of the Madonna, dance untiringly alongside. These festivities of the Neapolitans are traced to certain usages of their Greek ancestry, having possibly some relation to ancient Bacchanalian processions. FIRST SUNDAY MORNING OF MAY AT CRAIGIE WELL, BLACKISLE OF ROSSAmong the many relics of superstition still extant in the Highlands of Scotland, one of the most remarkable is the veneration paid to certain wells, which are supposed to possess eminent virtues as charms against disease, witchcraft, fairies, and the like, when visited at stated times, and under what are considered favourable auspices. Craigie Well is situated in a nook of the parish of Avoch, which juts out to the south, and runs along the north shore of the Munlochy bay. The well is situated within a few yards of high-water mark. It springs out between two crags or boulders of trap rock, and immediately behind it the ground, thickly covered with furze, rises very abruptly to the height of about sixty feet. Probably the name of the well is suggested by the numerous masses of the same loose rock which are seen to protrude in so many places here and there through the gorse and broom which grow round about. There is a large briar bush growing quite near the two masses of rock mentioned, which is literally covered with small threads and patches of cloth, intended as offerings to the well. None, indeed, will dare go there on the day prescribed without bringing an offering, for such would be considered an insult to the 'healing waters!' For more than a week before the morning appointed for going upon this strange pilgrimage, there is scarcely a word heard among farm servants within five miles of the spot, but, among the English speaking people, 'Art thee no ganging to Craigack wall, to get thour health secured another year? ' and, among the Gaelic speaking population, ' Dol gu topar Chreckack?' Instigated more by curiosity than anything else, I determined to pay this well a visit, to see how the pilgrims passed the Sunday morning there. I arrived about an hour before sunrise; but long before crowds of lads and lasses from all quarters were fast pouring in. Some, indeed, were there at daybreak, who had journeyed more than seven miles! Before the sun made his appearance, the whole scene looked more like a fair than anything else. Acquaintances shook hands in true highland style; brother met brother, and sister sister; while laughter and all manner of country news and gossip were so freely indulged in, that a person could hardly hear what he himself said. Some of them spoke tolerable English, others spoke Gaelic, while a third party spoke Scotch, very quaint in the phraseology and broad in the pronunciation. Meantime crowds were eagerly pressing forward to get a tasting of the well before the sun should come in sight; for, once he made his appearance, there was no good to be derived from drinking of it. Some drank out of dishes, while others preferred stooping on their knees and hands to convey the water directly to their mouths, Those who adopted this latter mode of drinking had sometimes to submit to the inconvenience of being plunged in over head and ears by their companions. This practice was tried, however, once or twice by strangers, and gave rise to a quarrel, which did not end till some blows had been freely exchanged. The sun was now shooting up his first rays, when all eyes were directed to the top of the brae, attracted by a man coming in great haste, whom all recognised as Jock Forsyth, a very honest and pious, but eccentric individual. Scores of voices shouted,' You are too late, Jock: the sun is rising. Surely you have slept in this morning.' The new-comer, a middle-aged man, with a droll squint, perspiring profusely, and out of breath, pressed nevertheless through the crowd, and stopped not till he reached the well. Then, muttering a few inaudible words, he stooped on his knees, bent down, and took a large draught. He then rose up and said: 'O Lord! thou knowest that weel would it be for me this day an' I had stooped my knees and my heart before thee in spirit and in truth as often as I have stoopet them afore this well. But we maun keep the customs of our fathers.' So he stepped aside among the rest, and dedicated his offering to the briar-bush, which by this time could hardly be seen through the number of shreds which covered it. Thus ended the singular scene. Year after year the crowds going to Craigach are perceptibly lessening in numbers. J. S. |