15th DecemberBorn: George Romney, portrait painter, 1734, Dalton, Lancashire; Jerome Bonaparte, youngest brother of Napoleon, 1784, Ajaccio. Died: Timoleon, liberator of Syracuse, 337 B.C.; Pope John VIII, 82 A.D.; Izaak Walton, author of The Complete Angler, 1683, Winchester; George Adam Struvius Jurist, 1692, Jena; Benjamin Stillingfleet, naturalist, 1771, Westminster; Jean Baptiste Carrier, revolutionary terrorist, guillotined, 1794; Mrs. Sarah Trimmer, authoress of juvenile and educational works, 1810, Brentford; David Don, botanist, 1841, London; Leon Faucher, eminent French statesman and publicist, 1854, Marseille. Feast Day: St. Eusebius, bishop of Vercelli, 371. WILLIAM HOGARTH

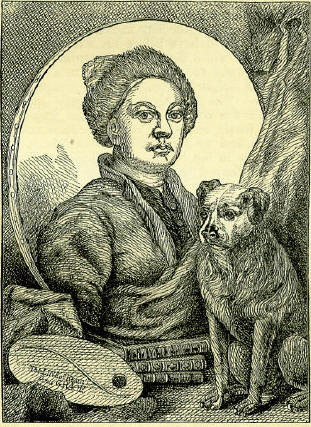

Were it desired to select from the distinguished men of Great Britain, one who should approach most nearly to the type of the true-born Englishman, with all his uprightness and honesty, his frank-hearted vivacity and genial joviality of temperament, and, at the same time, his roughness, obstinacy, and inveteracy of prejudice, no fitter representative of such aggregate qualities could be obtained than William Hogarth, our great pictorial moralist. Repulsive and painful as many of his subjects are, seldom exhibiting the pleasing or sunny side of human nature, their general fidelity and truthfulness commend themselves alike to the hearts of the most illiterate and the most refined, whilst the impressive, if at times coarsely-expressed, lessons which they inculcate, place the delineator in the foremost rank of those who have not inaptly been termed 'week-day preachers.' With the exception of two memorable excursions -one with a company of friends to Rochester and Sheerness, and another to Calais-Hogarth's life appears to have been almost exclusively confined to London and its immediate vicinity. His father, Richard Hogarth, was the youngest son of a Westmoreland yeoman, who originally kept a school at St. Bees, in Cumberland, but came up when a young man to London, and settled as a schoolmaster in Ship Court, in the Old Bailey. He married and had three children-William, afterwards the celebrated artist, and two girls, Mary and Anne. Young Hogarth, having early shewed a turn for drawing, was bound apprentice to a silversmith, and initiated in the art of engraving arms and cyphers on plate. The employment did not satisfy the aspirations of his genius, and he accordingly, on the expiration of his indentures, entered Sir James Thornhill's academy, in St. Martin's Lane, where he occupied himself in studying drawing from the life. In the mere delineation, however, of the external figure, irrespective of the exhibition of character and passion, Hogarth never acquired any great proficiency. During the first years of his artistic career, he supported himself by engraving arms and shop-bills; and then gradually ascending in the professional scale, he turned his attention successfully to portrait-painting, and in the course of a few years derived both a considerable income and reputation from this source. An amusing and characteristic anecdote of him is related in connection with this period of his life. A certain noble-man, remarkable for ugliness and deformity, employed Hogarth to paint his picture-a behest which the artist executed with only too scrupulous fidelity. The peer was disgusted at so correct a representation of himself, and refused to take or pay for the picture. After numerous ineffectual negotiations with his lordship on the subject, Hogarth addressed him the following note: Mr. Hogarth's dutiful respects to Lord -; finding that he does not mean to have the picture which was drawn for him, is informed again of Mr. Hogarth's pressing necessities for the money. If, therefore, his lordship does not send for it in three days, it will be disposed of, with the addition of a tail and some other appendages, to Mr. Hare, the famous wild-beast man; Mr. H. having given that gentleman a conditional promise on his lordship's refusal.' The ruse was successful; the price agreed on was paid for the picture, which was forthwith destroyed. Having attained the age of thirty-three, Hogarth contracted, in 1730, a secret marriage with the only daughter of the celebrated painter, Sir James Thornhill, who was at first extremely indignant at the match. He afterwards, however, relented, and lived till his death in great harmony with his son-in-law. With the publication of the 'Harlot's Progress,' in 1733, Hogarth commenced those serial prints which have rendered his name immortal. From the first, his success in this department of art was assured. The 'Harlot's Progress' was followed, after the interval of two years, by the still more famous 'Rake's Progress,' and this again by the series of 'Marriage h la Mode,' 'Industry and Idleness,' the 'Stages of Cruelty,' and the 'Election Prints.' Numerous other individual pieces might be mentioned, such as the 'March to Finchley,' which excited the wrath of George II, by the ludicrous light in which his soldiers were presented; 'Modern Mid-night Conversation,' 'Strolling Players in a Barn,' and 'Beer Street,' and 'Gin Lane;' the former a plea for the liquor which Hogarth, like a true Englishman, deemed the most wholesome and generous beverage; the latter, a fearfully repulsive, hut at the same time salutary delineation of the dreadful miseries resulting from the abuse of ardent spirits. To another picture by Hogarth, 'The Gate of Calais,' a curious anecdote is attached. He had made an excursion thither with some friends, but with the determination apparently to find nothing in France either pleasing or commendable. Like Smollett, Hogarth seems to have entertained a thorough con-tempt for the French nation, and he was unable to refrain from giving vent to his sentiments even in the open street. The lank and grotesque figures which presented themselves everywhere, and by their appearance gave unmistakable evidence of the poverty and misery of the country, under the old regime, called forth all his powers of ridicule; whilst the light-heartedness and vivacity with which, like the Irish, the French people could forget or charm away their wretchedness, raised only to a higher pitch his feeling of contempt. Very speedily and summarily, however, he himself was obliged to quit the country which he so heartily despised. Ignorant of foreign jealousies on the subject of bulwarks and fortifications, he began to make a sketch of the gate of Calais, as a curious piece of architecture. This action being observed, he was arrested as a spy, and conveyed by a file of musketeers before the governor of the town. There his sketch-book was examined, but nothing whatever was discovered to warrant the suspicion entertained against him. The governor, however, assured him with the utmost politeness, that were it not for the circumstance of the preliminaries of a treaty of peace having actually been signed between England and France, he should have been under the disagreeable necessity of hanging Mr. Hogarth on the ramparts of Calais. As it was, he must insist on providing him with a military escort whilst he continued in the dominions of Louis XV. The discomfited artist was then conducted by two sentinels to his hotel, and from thence to the English packet in the harbour. Hogarth's guard of honour accompanied him to the distance of about a league from the shore, and then seizing him by the shoulders, and spinning him round upon the deck, they informed him that he was now at liberty to pursue his voyage without further molestation. Hogarth reproduced this adventure in the print above referred to, where, in addition to the grotesque figures who fill up the centre and foreground of the picture, he himself is delineated standing in a corner, and making a sketch of the gateway of the town, whilst the hand of a sentinel is in the act of being laid on the artist's shoulder. Though he thus perpetuates the recollection of the circumstance, it is said that he never liked to hear any reference to the mortifying incident that ensued. In a letter from Horace Walpole to Sir Horace Mann, dated 15th December 1748, this misadventure of Hogarth is communicated as a piece of news which had just transpired. Hogarth's prints are thus admirably epitomised by Mr. Thackeray in his English Humorists: They give us the most complete and truthful picture of the manners, and even the thoughts, of the past century. We look, and see pass before us the England of a hundred years ago-the peer in his drawing-room, the lady of fashion in her apartment, foreign singers surrounding her, and the chamber filled with gewgaws in the mode of that day; the church, with its quaint florid architecture and singing congregation; the parson with his great wig, and the beadle with his cane: all these are represented before us, and we are sure of the truth of the portrait. We see how the lord mayor dines in state; how the prodigal drinks and sports at the bagnio; how the poor girl beats hemp in Bridewell; how the thief divides his booty, and drinks his punch at the night-cellar, and how he finishes his career at the gibbet. We may depend upon the perfect accuracy of these strange and varied portraits of the bygone generation; we see one of Walpole's members of parliament chaired after his election, and the lieges celebrating the event, and drinking confusion to the Pretender; we see the grenadiers and trainbands of the city marching out to meet the enemy; and have before us, with sword and firelock, and white Hanoverian horse embroidered on the cap, the very figures of the men who ran away with Johnny Cope, and who conquered at Culloden. The Yorkshire wagon rolls into the inn-yard; the country parson, in his jack-boots, and his bands and short cassock, comes trotting into town, and we fancy it is Parson Adams, with his sermons in his pocket. The Salisbury fly sets forth from the old 'Angel '-you see the passengers entering the great heavy vehicle, up the wooden steps, their hats tied down with handkerchiefs over their faces, and under their arms, sword, hanger, and case-bottle; the landlady-apoplectic with the liquors in her own bar-is tugging at the bell; the hunchbacked postilion-he may have ridden the leaders to Humphry Clinker-is begging a gratuity; the miser is grumbling at the bill; Jack of the Centurion lies on the top of the clumsy vehicle, with a soldier by his side-it may be Smollett's Jack Hatchway-it has a likeness to Lesmahago. You see the suburban fair, and the strolling company of actors; the pretty milkmaid singing under the windows of the enraged French musician-it is such a girl as Steele charmingly described in the Guardian, a few years before this date, singing, under Mr. Ironside's window in Shire Lane, her pleasant carol of a May morning. You see noblemen and blacklegs bawling and betting in the cock-pit; you see Garrick as he was arrayed in King Richard; Macheath and Polly in the dresses which they wore when they charmed our ancestors, and when noblemen in blue ribbons sat on the stage, and listened to their delightful music. You see the ragged French soldiery, in their white coats and cockades, at Calais Gate-they are of the regiment, very likely, which friend Roderick Random joined before he was rescued by his preserver, Monsieur de Strap, with whom he fought on the famous day of Dettingen. You see the judges on the bench; the audience laughing in the pit; the student in the Oxford theatre; the citizen on his country-walk; you see Broughton the boxer, Sarah Malcolm the murderess, Simon Lovat the traitor, John Wilkes the demagogue, leering at you with that squint which has become historical, and that face which, ugly as it was, he said he could make as captivating to woman as the countenance of the handsomest beau in town. All these sights and people are with you. After looking in the Rake's Progress at Hogarth's picture of St. James's Palace-gate, you may people the street, but little altered within these hundred years, with the gilded carriages and thronging chairmen that bore the courtiers, your ancestors, to Queen Caroline's drawing-room, more than a hundred years ago. Hogarth was not only a painter and an engraver, but likewise an author, having published, in 1753, a quarto volume, entitled the Analysis of Beauty, in which he maintains the fundamental principle of beauty to consist in the curve or undulating line, and that round swelling figures are the most attractive to the eye. This idea appears to have been cherished by him with special complacency, as in that characteristic picture which he painted of himself and his clog Trump, and of which a copy is here engraved, he has inscribed, in association with the curve, 'The Line of Beauty and Grace,' as his special motto. A very curious and interesting memorial of Hogarth and his associates, exists in the narration of a holiday excursion down the river as far as Sheerness. Though Hogarth himself is not the chronicler, we are favoured, by one of the party, with a most graphic description of this merry company, who seem to have enjoyed their trip with all the zest of school-boys or young men 'out on a lark.' Hogarth acted as draughtsman, making rough sketches of many of the incidents of the journey, which seems to have been as jovial an expedition as good-humour, high spirits, and beer, could have contributed to effect. One of the members of this party was Hogarth's brother-in-law, John Thornhill, who afterwards became sergeant-painter to the king, but resigned his office in favour of Hogarth in 1757. It has been imagined that this connection with the court, in his latter years, led the artist into that pictorial warfare with Wilkes and Churchill, in which certainly no laurels were gathered by any of the parties engaged. Hogarth's health began now visibly to decline, and after languishing in this state about two years, he expired suddenly, of aneurism in the chest, on 25th October 1764. He was interred in the churchyard at Chiswick, where a monument, recently restored, was erected to his memory. He never had any family, and was survived for twenty-five years by his wife, who died in 1789. THE SOCIETY OF THE PIUAt the beginning of the fourteenth century, London contained many foreigners, whose business it was to frequent the various fairs and markets held in England, and with whom their idle time hung heavily for want of some congenial amusement. To meet this want, they formed a semi-musical, semi-friendly association, called the Company or Brotherhood of the Piu-'in honour of God, our Lady Saint Mary, and all saints both male and female; and in honour of our lord the king, and all the barons of the country.' Both the name and nature of the association were derived from similar societies then existing in France and Flanders, which are supposed to have taken their titles from the city of Le Puy, in Auvergne, a city rejoicing in the possession of a famous statue of the Virgin, popular with the pilgrims of the age. The rules and regulations of the London society are preserved in the Liber Custumarum, one of the treasures of the Guildhall library. From these we learn that the avowed object of the loving companions of the Piu, was to make London renowned for all good things; to maintain mirth, peace, honesty, joyousness, and love; and to annihilate wrath and rancour, vice and crime. The brotherhood, which was not confined to foreigners, consisted of an unlimited number of members, each of whom paid an entrance-fee of sixpence, and an annual subscription of one shilling, towards the expenses of the yearly festival. The management of the society's affairs was intrusted to twelve companions, who held office till removed by death or their secession from the brotherhood, but the president or prince, as he was called, was changed every year. Any member was eligible to serve, and none could decline the office if chosen by the outgoing prince-his choice being ratified by eleven of the twelve companions declaring him, upon oath, to be 'good, loyal, and sufficient' The expense entailed by accepting the honour was not very burdensome, consisting merely in paying for the official costume, 'a coat and surcoat without sleeves, and mantle of one suit, with whatsoever arms he may please.' The crown was provided by the society at the cost of one mark, and was passed from one prince to another. The only other officers were a clerk to keep the accounts, register the names of the members, and summon them to the meetings of the company; and a chaplain, 'at all times singing mass for living and dead companions.' To suit the convenience of the mercantile community, the great festival of the Piu was held on the first Sunday after Trinity, in a room strewed with fresh rushes, and fairly decked with leaves. As soon as the company were assembled, the investiture of the new prince took place, with the following simple ceremony: The old prince and his companions shall go through the room, from one end to the other, singing; and the old prince shall carry the crown of the Piu upon his head, and a gilt cup full of wine in his hands. And when they shall have gone round, the old prince shall give to drink unto him whom they shall have chosen, and shall give him the crown, and such person shall be prince. The blazon of the new chief's arms were then hung in a conspicuous place, and the most important business of the day commenced. This was the choosing of the best song. The competitors-who were exempted from paying the festival-fee-were ranged on a seat covered with cloth of gold, the only place allowed to be so decorated. The judges were the two princes and a jury of fifteen members, who took an oath not to be biassed in their judgment, 'for love, for hate, for gift, for promise, for neighbourhood, for kindred, or for any acquaintanceship old or new, nor yet anything that is.' Further to insure the prize being properly awarded, it was decreed that, 'there be chosen two or three who well understand singing and music, for the purpose of trying and examining the notes, and the points of the songs, as well as the nature of the words composed thereto. For without singing, no one ought to call a composition of words, a song; nor ought any royal song to be crowned without the sweet sounds of melody sung.' When the song had been chosen, it was hung beneath the arms of the prince, and its author crowned. Then dinner was served, each guest receiving good bread, ale and wine, pottage, one course of solid meat, double roast in a dish, cheese, 'and no more.' At the conclusion of this moderate banquet, the whole company rose, mounted their horses, and went in procession through the city, headed by the princes past and present, between whom rode the musical champion of the meeting. On arriving at the house of the new prince, the brethren dismounted, had a dance by way of a hearty good-bye,' and departed home-ward on foot. None but members of the company were invited to the festival, and ladies were especially excluded from taking part in it, by a clause which is a curiosity in its way, as a gallant excuse for an ungallant act. It runs thus: Although the becoming pleasances of virtuous ladies is a rightfultheme and principal occasion for royal singing, and for composing and furnishing royal songs, nevertheless it is hereby provided that no lady or other woman ought to be at the great feast of the Piu, for the reason that the companions ought hereby to take example and rightful warning to honour, cherish, and commend all ladies, at all times, in all places, as much in their absence as in their presence. The day after the feast a solemn mass was sung at the priory of St. Helen's for the souls of all Christian people in general, and those of the brotherhood in particular. The accounts were audited, and any surplus left, added to the treasury of the company; if the expenses of the feast exceeded the receipts, the difference was made good by contributions from the members. The names of absentees in arrears were published, and those who had neglected paying their subscription for seven years were expelled the society, the same sentence being passed against evil-minded companions, respecting whom there was this emphatic statute: If there be any one who is unwilling to be obedient to the peace of God, and unto the peace of our lord the king-whom God preserve-the community of the companions do not wish to have him or his fees, through whom the company may be accused or defamed. Members were also expected to attend at the wedding or funeral of a brother, and were further-more enjoined always to aid, comfort, and counsel one another in faith, loyalty, peace, love, and concord as brethren in God and good love. NEGRO AUTHORSThere are so very few instances on record of any of the pure African negro race exhibiting a taste or ability for literary composition, that their names seem not unworthy of notice in this collection. First in the list stands Ignatius Sancho, who was born in 1729, on board of a slave-ship, a few days after leaving the coast of Guinea, for the Spanish-American colonies. At Carthagena, he was christened Ignatius; his mother died soon after, and his father, unable to survive her, avoided the miseries of slavery by suicide. When two years of age, Ignatius was brought to England, and given by his owner as a present to three elderly maiden-sisters, residing near Greenwich. These ladies, having just previously read Don Quixote, gave their little slave the name of Sancho; but, however fond of reading themselves, they denied that advantage to Ignatius, believing that ignorance was the only security for obedience; that to cultivate the mind of their slave, was equivalent to emancipating his person. Happily, the Duke of Montague, then residing at Blackheath, near Greenwich, saw the little negro, and admired in him a native frankness of manner, as yet unimpaired by servitude, if unrefined by education. Learning that the child was trying to educate himself, the duke lent him books, and strongly recommended to his three mistresses the duty of cultivating a mind of such promising ability. The ladies, however, remained inflexible; it was of no use to educate the lad, they said, as they had determined to send him back to West Indian slavery. At this crisis, the duke died; and, the duchess declining to interfere between the negro-lad and his mistresses, Sancho, in the immediate prospect of being sent away, fell into a state of despair. With four shillings, all the wealth he possessed, he bought a pistol, and threatened to follow the example of his father. The ladies, now terrified in their turn, gave up all claim to their slave, and he was taken into the service of the Duchess of Montague. In this family Sancho served, principally in the capacity of butler, for many years, till corpulence and gout rendered him unfit for duty. He then set up a small grocer's shop, and by care and industry gained a decent competence to support his family till his death, which took place on the 15th of December 1780. Sancho corresponded with many notabilities of his day, such as Sterne, Garrick, and the few persons who then took an interest in the abolition of the slave-trade. His letters were published after his death, edited by a Miss Crewe, who, as she says, did not give them to the public till she had obviated an objection which had been advanced, that they were originally written with the view of publication. She declares that no such idea was ever entertained by Sancho; that not one letter was printed from a copy or duplicate preserved by him-self, but all collected from the various friends to whom he had written them. She also adds, that her reasons for publishing them, were her desire of showing that an African may possess abilities equal to a European; and the stilt superior motive of serving a worthy family. In this undertaking Miss Crewe had the happiness of finding that the world was not inattentive to the voice of obscure merit. The first and second editions of Sancho's letters produced £500 to his widow and family, and the writer has seen a fifth edition, published more than twenty years after his death, by his son, William Sancho, then a respectable bookseller in Westminster. Attobah Cugoana, a Fantin negro, was carried as a slave to Grenada, when quite a child. Meeting with a benevolent master, he was subsequently liberated and sent to England, where he entered the service of Mr. Cosway, the celebrated portrait-painter. Little is known of this negro's history, though it would seem that he was a much abler man than Sancho, with less advantages of education and the assistance of influential friends. He was the author of a work of considerable celebrity in its day, entitled Thoughts and Sentiments on the evil and wicked Traffic of the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species: Humbly submitted to the Inhabitants of Great Britain. This is certainly an ably composed book, containing the essence of all that has been written against slavery from a religious point of view; and though the matter is ill arranged, and some of the arguments scarcely logical, it was translated into French, and obtained great consideration among the continental philanthropists. Another interesting example of literary distinction achieved by what Thomas Fuller, with a quaintness and benevolence of phrase peculiarly his own, styles 'God's image cut in ebony,' is afforded by Phillis Wheatley, an African negress, who, when about seven years of age, was brought to Boston as a slave in 1761. She was purchased by a respectable merchant, named Wheatley, who had her christened Phillis, and, according to custom, her master's surname was bestowed on her. She never received any instruction at school, having been taught to read by her master's family; the art of writing she acquired herself. Phillis composed a small volume of poems, which was published in her nineteenth year. Like many others of her race, she vainly hoped that the quarrel between the mother-country and the American colonies would be beneficial to African freedom; that when independence was gained by the white man, the black would be allowed some share in the precious boon. In a poem on Freedom, addressed to the Earl of Dartmouth, the secretary of state for the colonies, she thus writes: Should you, my lord, while you pursue my song, Wonder from whence my love of freedom sprung, Whence flow those wishes for the common good, By feeling hearts alone best understood- I, young in life, by seeming cruel fate, Was snatched from Afric's fancied happy seat. What pangs excruciating must molest, What sorrows labour in my parent's breast? Steeled was that soul, and by no misery moved, That from a father seized the babe beloved. Such, such my case-and can I then bat pray, Others may never feel tyrannic sway? Phillis married a person of her own complexion, a tradesman in comfortable circumstances in Boston. Her married life was unhappy. From the notice bestowed on Phillis by persons of station and influence, her husband, with the petty jealousy common to his race, felt hurt that his wife was respected more than himself. In consequence, he behaved to her harshly and cruelly, and she, sinking under such treatment, died in her twenty-sixth year, much regretted by those capable of appreciating her modest talents and virtues. |