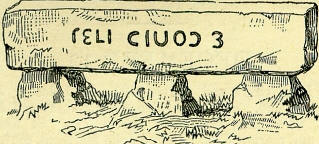

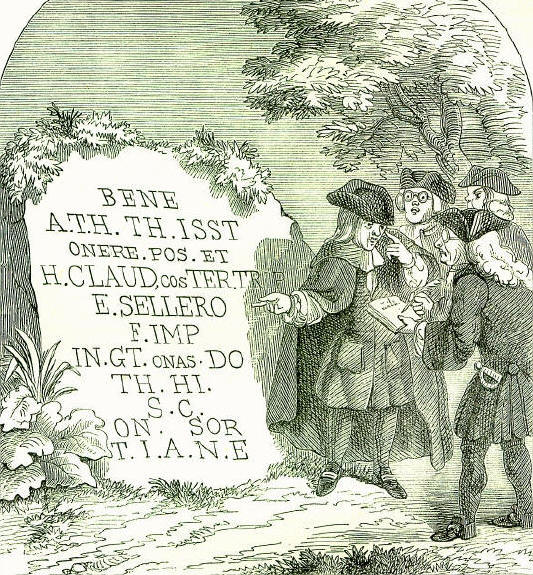

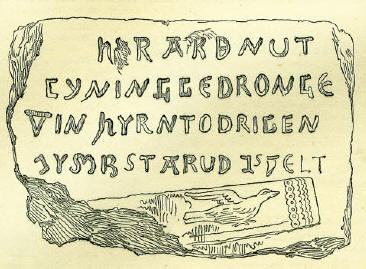

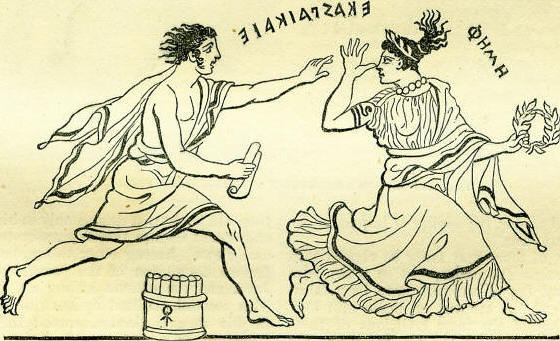

13th DecemberBorn: Pope Sixtus V, 1521, Montalto; Henri IV of France, 1553, Pau; Maximilien de Bethune, Duke of Sully, minister of Henri IV, 1560, Rosny; William Drummond, poet, 1585, Hawthornden; Rev. Arthur Penrhyn Stanley, biographer of Dr. Arnold, 1815. Died: Emperor Frederick II of Germany, 1250; Emanuel the Great, king of Portugal, 1521; James V of Scotland, 1542, Falkland; Conrad Gesner, eminent naturalist, 1565, Zurich; Anthony Collins, freethinking writer, 1729; Rev. John Strype, historical writer, 1737, hackney; Christian Furchtegott Gellert, writer of fables, 1769, Leipsic; Peter Wargentin, Swedish astronomer, 1783, Stockholm; Dr. Samuel Johnson, lexicographer, 1784, London; Charles III of Spain, 1788. Feast Day: St. Lucy, virgin and martyr, 304. St. Jodoc or. Josse, confessor, 666. St. Aubert, bishop of Cambray and Arras, 669. St. Othilia, virgin and abbess, 772. St. Kenelm, king and martyr, 820. Blessed John Marinoni, confessor, 1562. ST. LUCYSt. Lucy was a native of Syracuse, and sought in marriage by a young nobleman of that city; butshe had determined to devote herself to a religious life, and persistently refused the addresses of her suitor, whom she still further exasperated by distributing the whole of her large fortune among the poor. He thereupon accused her to the governor, Paschasius, of professing Christian doctrines, and the result was her martyrdom, under the persecution of the Emperor Dioclesian. A curious legend regarding St. Lucy is, that on her lover complaining to her that her beautiful eyes haunted him day and night, she cut them out of her head, and sent them to him, begging him now to leave her to pursue, unmolested, her devotional aspirations. It is added that Heaven, to recompense this act of abnegation, restored her eyes, rendering them more beautiful than ever. In allusion to this circumstance, St. Lucy is generally represented bearing a platter, on which two eyes are laid; and her inter-cession is frequently implored by persons labouring under ophthalmic affections. THE EMBER-DAYSThe Ember-days are periodical fasts originally instituted, it is said, by Pope Calixtus, in the third century, for the purpose of imploring the blessing of Heaven on the produce of the earth; and also preparing the clergy for ordination, in imitation of the apostolic practice recorded in the 13th chapter of the Acts. It was not, however, till the Council of Placentia, 1095 A.D., that a uniformity as regards the season of observance was introduced. By a decree of this assembly, it was enacted that the Ember-days should be the first Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday following, respectively, the first Sunday in Lent, or Quadragesima Sunday, Whitsunday, Holyrood Day (14th September), and St. Lucy's Day (13th December). The term is said to be derived from the Saxon embrem or imbryne, denoting a course or circuit, these days recur-ring regularly, at stated periods, in the four quarters or seasons of the year. Others, with some plausibility, derive the epithet from the practice of sprinkling dust or embers on the head, in token of humiliation; and also from the circumstance that at such seasons it was only customary to break the fast by partaking of cakes baked on the embers, or ember-bread. In accordance with a canon of the English Church, the ordination of clergymen by the bishop generally takes place on the respective Sundays immediately following the ember-days. The weeks in which these days fall, are termed the Ember-weeks, and in Latin the ember-days are denominated Jejunia quatuor temporum, or 'the fasts of the four seasons.' THE COUNCIL OF TRENTThis celebrated council, the last which has been summoned by the Roman Catholic Church, was formally opened on 13th December 1545, and closed on 4th December 1563. Its sittings extended thus, with various prorogations, over a period of eighteen years, and through no less than five pontificates, commencing with Paul III, and ending with Pius IV. The summoning of a general council had been ardently desired by the adherents both of the Roman Catholic and Reformed systems, partly from a desire to have many great and scandalous abuses removed, partly from the hope of effecting a reconciliation between the opposite faiths, through mutual concession and an adjustment of the points in dispute by the decision of some authoritative assembly. The requisition to convoke such a meeting was first made to Clement VII, and was seconded, with all his influence, by the Emperor Charles V; but, as is well known, popes have ever had the greatest dislike of general councils, regarding them as dangerous impugners of their pretensions, and at the present conjuncture no proposal could have been more distasteful. Well knowing the ecclesiastical abuses that prevailed, and fearful of the consequences of inquiry and exposure, Clement, by various devices, contrived, for the short remainder of his life, to elude compliance with the unpalatable proposition. But his successor, Paul III, found himself unable, with any appearance of propriety, to postpone longer a measure so earnestly desired, and he accordingly issued letters of convocation for a general ecclesiastical council. After much disputation, the town of Trent, in the Tyrol, was fixed on as the place of meeting of the assembly. But with all the preliminary arrangements entered into, the German Protestant subjects of Charles V were thoroughly dissatisfied. The place chosen for the meeting was unsuitable from its remote situation, and an infinitely weightier objection was made to the right assumed by the pope of presiding in the council and directing its deliberations, together with the refusal to guarantee, throughout the proceedings, the recognition of the Scriptures, and the usage of the primitive church, as the sole standards of faith. After some abortive attempts to accommodate these differences, the Protestants finally declined to attend or recognise in any way the approaching council, which was accordingly left wholly to the direction of the Catholics. One of the first points determined was: That the books to which the designation of Apocryphal hath been given, are of equal authority with those which were received by the Jews and primitive Christians into the sacred canon; that the traditions handed down from the apostolic age, and preserved in the church, are entitled to as much regard as the doctrines and precepts which the inspired authors have committed to writing; that the Latin translation of the Scriptures, made or revised by St. Jerome, and known by the name of the Vulgate translation, should be read in churches, and appealed to in the schools as authentic and canonical. In virtue of its infallible authority, claimed to be derived from the immediate inspiration of the Holy Spirit, the council denounced anathemas against all those who should impugn or deny the validity of its decisions. The ancient formula, however, prefixed by ecclesiastical councils to their deliverances-It has seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us-was, on the occasion of the assembly at Trent, exchanged for the milder phrase -In the presence of the Holy Spirit it has seemed good to us. This specimen, given by the council at the commencement of its proceedings, was sufficiently indicative of the results to be eventually expected. So far from any modification being effected in the tenets or claims of the Roman Catholic Church and its ministers, these, on the contrary, were more rigorously enforced and defined. In the words of Dr. Robertson ' Doctrines which had hitherto been admitted upon the credit of tradition alone, and received with some latitude of interpretation, were defined with a scrupulous nicety, and confirmed by the sanction of authority. Rites, which had formerly been observed only in deference to custom, supposed to be ancient, were established by the decrees of the church, and declared to be essential parts of its worship. The breach, instead of being closed, was widened and made irreparable.' While thus so antagonistic to Protestant views, the decrees of the Council of Trent are generally regarded as one of the principal standards and completed digests of the Roman Catholic faith. ANTIQUARIAN HOAXESOne of the most amusing traits in the character of Sir Walter Scott's kind-hearted antiquary, the estimable Monkbarns, is his perfect reliance on his own rendering of the letters A. D. L. L., on a stone he believes to be antique, and which letters he amplifies into Agricola dicavit libens lubens; a theory rudely demolished by Edie Ochiltree, who pronounces 'the sacrificial vessel,' also on the stone, to be the key to its true significance, Aikin Drum's lang ladle. Scott had 'ta'en the antiquarian trade' (as Burns phrases it) early in life, and commenced his literary career in that particular walk; his early rambles on the line of the great Roman Wall, in the Border counties, would familiarise him with inscriptions; and his acquaintance with antiquarian literature lead him to the knowledge of a few mistakes made in works of good repute. In depicting the incident above referred to, he might have had in his mind the absurd error of Vallancey, who has engraved in his great work on Irish Antiquities, a group of sepulchral stones on the hill of Tara, having upon one an inscription which he reads thus: BELI DIVOSE, 'To Belus, God of Fire.' He indulges, then, in a long and learned disquisition on this remarkable and unique inscription; which he has also so carefully engraved, that its real significance may easily be tested.  It turned out to be the work of an idler, who lay upon the stone, and cut his name upside down with the date of the year: E. CONID. 1731; and if the reader will turn the engraving to the right , the whole thing becomes clear, and Baal is deprived of his altar. Dean Swift had successfully shewn how a choice of words, and their arrangement, might make plain English look exceedingly like Latin. The idea was carried out further by some wicked wit, who, aided by a clever engraver, produced, in 1736, a print called 'The Puzzle,' which has never been surpassed in its peculiar style. 'This curious inscription is humbly dedicated,' says its author, 'to the penetrating geniuses of Oxford, Cambridge, Eton, and the learned Society of Antiquaries.' The first, fourth, sixth, and three concluding lines are particularly happy imitations of a Latin inscription. It is, however, a simple English epitaph; the key, published soon afterwards, tells us: The inscription on the stone, without having regard to the stops, capital letters, or division of the words, easily reads as follows: 'Beneath this stone reposeth Claud Coster, tripe-seller of Impington, as doth his consort Jane.'  Such freaks of fancy may fairly be classed with Callot's Impostures Innocentes; not so when false inscriptions and forged antiques have been fabricated to mislead the scholar, or make him look ridiculous. One of the most malicious of these tricks was concocted by George Steevens, the Shakspearian commentator, to revenge himself on Gough, the director of the Society of Antiquaries of London, and author of the great work on our Sepulchral Monuments. The entire literary life of Steevens has been characterised as displaying an unparalleled series of arch deceptions, tinctured with much malicious ingenuity. He scrupled not, when it served his purpose, to invent quotations from old books that existed only in his imagination, and would deduce therefrom corroboration of his own views. Among other things, he invented the famous description of the poisonous upas-tree of Java, and the effluvia killing all things near it. This account, credited by Darwin, and introduced in his Botanic Carden, spread through general literature as a fact; until artists at last were induced to present pictures of the tree and the deadly scene around it. Steevens chose the magazines, or popular newspapers, for the promulgation of his inventions, and signed them with names calculated to disarm suspicion. It is impossible to calculate the full amount of mischief that may be produced by such means-literature may be disfigured, and falsehood take the place of fact.  The Hardicanute Marble The trick on Gough was the fabrication of an inscription, purporting to record the death of the Saxon king, Hardicanute, and was done in revenge for some adverse criticism Gough had pronounced on a drawing of Steevens. Steevens vowed that, wretched as Gough deemed his work, it should have the power to deceive him. He obtained the fragment of a chimney-slab, and scratched upon it an inscription in Anglo-Saxon letters, to the effect that 'Here Hardenut drank a wine-horn dry, stared about him, and died.' It was alleged to have been discovered in Kennington Lane, where the palace of the monarch was also said to have been, and the fatal drinking-bout to have taken place. The stone was placed carelessly among other articles in a shop where Gough frequently called. He fell fairly into the trap; and brought forward his imagined prize, as a great historic curiosity, to the notice of the Society of Antiquaries. One of the ablest members of the association-the Rev. S. Pegge -was induced to write a paper on the subject. Schnebbelie, the draughtsman of the society, was employed to draw the inscription carefully, and it was engraved, and published in vol. lx. of the Gentleman's Magazine, from which our cut is copied. The falsely-formed letters, and absurd tenor of the whole inscription, would deceive no one now. Luckily, before its publication in the Magazine, its history was discovered; but as the plate contained other subjects, it was nevertheless issued, with a note of warning appended. Steevens, however, followed up his success with a bitter description of the triumph of his fraud, and the impossibility of Gough's 'wriggling off the hook on which he is so archaeologically suspended.' Instances might be readily multiplied of similar deceptive inventions; indeed, the history of falsehood and forgery in connection with antiquities is as vast as it is still unceasing. Rome and Naples are today what Padua was in the sixteenth century the birthplace of spurious curiosities, manufactured with the utmost art, and brought forth with the greatest apparent innocence. Nothing is forgotten to be done that may effectually deceive; and the unguarded stranger may see objects dug out of ruins apparently ancient, that have been recently made, and placed there for his delectation. A brisk trade in painted vases has always been carried on; and many of them, evidently false, have been published in works of high character.  Fame eluding her followers Birch, in his History of Ancient Pottery, speaks of this, and adds: 'One of the most remarkable fabricated engravings of these vases was that issued by Brondsted and Stackelberg, in a fit of archaeological jealousy. A modern archaeologist is seen running after after a draped female figure called Fame; who flies from him, exclaiming 'Be off, my fine fellow!' This vase, which never existed except upon paper, deceived the credulous Inghirami, who, too late, endeavoured to expunge it from his work.' Consequently his valuable book on Vasi Fittili is disfigured by this absurd invention, and our cut is traced from his plate. These mischievous tricks compel the student to double labour-he has not only to use research, but to be assured that what he finds may be depended on. Supposed facts may turn out to be absurd fictions, and the stream of knowledge be poisoned at its very source. THE NINE WORTHIES OF LONDONEverybody has read, or at least heard, of the famous History of the Seven Champions of Christendom, but few, we suspect, have either read or heard of another work by the same author, which, if less interesting than the chivalric chronicle dear to boyhood, has the merit of being to some extent founded on fact. In the year 1592, Mr. Richard Johnson gave to the world The Nine Worthies of London; explaining the honourable Exercise of Arms, the Virtues of the Valiant, and the Memorable Attempts of Magnanimous Minds; pleasant for Gentlemen, not unseemly for Magistrates, and most profitable for 'Prentices'. This chronicle of the deeds of city-heroes is a curious compound of prose and verse. The Worthies are made to tell their own stories in rhyme, to a prose accompaniment unique in its way. What that way is, may be judged by the following quotation from the fanciful prelude: What time Fame began to feather herself to fly, and was winged with the lasting memory of martial men; orators ceased to practise persuasive orations, poets neglected their lyres, and Pallas herself would have nothing painted on her shield save mottoes of Mars, and emblems in honour of noble achievements. Then the ashes of ancient victors, without scruple or disdain, found sepulture in rich monuments; the baseness of their origin shaded by the virtue of their noble deeds. Fame, however, was still fearful of her honour growing faint, and, in her fear, betook herself to Parnassus, and invoked the aid of the Muses in order to revive ' what ignorance in darkness seems to shade, and hateful oblivion hath almost rubbed out of the book of honour-the deeds not of kings, but of those whose merit made them great.' Choosing Clio as her companion, Fame re-entered her chariot, and speedily reached the Elysian Fields, where, upon a rose-covered bank, nine handsome knights lay asleep; waking them up, she desired them to tell their several adventures, that Clio might take them down for the benefit of mankind in general, and London 'prentices in particular. Then forth stepped Sir William Walworth, fishmonger, twice lord mayor of London (in 1374 and 1380). His narrative begins and ends with the great event of his second mayoralty-the rebellion of Wat Tyler. He relates how the malcontents advanced to London, mightily assailed the Tower walls, and how: Earle's manner houses were by them destroyed; The Savoy and S. Jones by Smithfield spoiled. While- All men of law that fell into their hands They left them breathless, weltering in their blood; Ancient records were turned to firebrands, Any had favour sooner than the good: So stout these cut-throats were in their degree, That noblemen must serve them on their knee. To protect the person of the young king when he went to meet the rebels at Smithfield, Walworth attended with A loyal guard of bills and bows Collected of our tallest men of trade. During the parley with Wat Tyler, the sturdy magistrate sat chafing with anger at the audacity of the blacksmith's followers, but refrained from interfering, because his betters were in place, till he could control himself no longer: Twere service good (thought I) to purchase peace, And malice of contentious brags assuage, With this conceit all fear had taken flight, And I, alone, pressed to the traitors' sight. Their multitude could not amaze my mind, Their bloody weapons did not make me shrink, True valour hath his constancy assigned, The eagle at the sun will never wink. Among their troops incensed with mortal hate, I did arrest Wat Tyler on the pate. The stroke was given with so good a will, I made the rebel conch unto the earth; His fellows that behind (though strange) were still, It marred the manner of their former mirth. I left him not, but ere I did depart, I stabbed my dagger to his damned heart. For which daring deed Richard immediately dubbed him a knight. A costly hat his Highness likewise gave; That London's maintainance might ever be, A sword also he did ordain to have, That should be carried still before the mayor, Whose worth deserved succession to the chair. The second speaker is Sir Henry Pitchard, who commences his story with an atrocious pun: The potter tempers not the massive gold, A meaner substance serves his simple trade, His workmanship consists of slimy mould, Where any placed impression soon is made. His Pitchards have no outward glittering pomp, As other metals of a firmer stamp. After serving in the wars of Edward III, Pitchard set up as a vintner, and throve so well that he was elected lord mayor (1356); he hints that he could speak of liberal deeds, but prefers to rest his claim to honourable consideration upon his anxiety for the advance of London's fame, and the part he played on Edward's return from France with 'three crowns within his conquering hand.' As from Dover with the prince his son, The kings of Cyprus, France, and Scots did pass, All captive prisoners to this mighty, one, Five thousand men, and I their leader was, All well prepared, as to defend a fort, Went forth to welcome him in martial sort. When the city 'peared within our sights, I craved a boon, submisse upon my knee, To have his grace, these kings, with earls and knights, A day or two, to banquet it with me, The king admired, yet thankfully replied: 'Unto thy house, both I and these will ride.' The royal guests and their followers were right hospitably entertained: For cheer and sumptuous cost no coin did fail, And he that thought of sparing did me wrong. This truly civic 'achievement is at once admitted by Clio to justify Pitchard's enrolment among the Worthies Nine. Sir William Sevenoke tells how he was found under seven oaks, near a small town in Kent, and after receiving some education, was apprenticed to a grocer in London. His apprenticeship having expired, he went with Henry V to France, where: The Dolphyne [Dauphin] then of France, a comely knight, Disguised, came by chance into a place Where I, well wearied with the heat of fight, Had laid me down, for war had ceased his chace; And, with reproachful words, as lazy swain He did salute me ere I long had lain. I, knowing that he was mine enemy, A bragging Frenchman (for we termed them so), Ill brooked the proud disgrace he gave to me, And therefore lent the Dolphyne such a blow, As warned his courage well to lay about, Till he was breathless, though he were so stout. At last the noble prince did ask my name, My birth, my calling, and my fortunes past; With admiration he did hear the same, And so a bag of crowns he to me cast; And, when he went away, he said to me: 'Sevenoke, be proud, the Dolphyne fought with thee! The war over, Sevenoke determined to turn grocer again, and in time became famous for his wealth. [In 1413, Sevenoke was made sheriff; in 1418, he was elected lord mayor; and, two years later, he represented London in parliament. By his will, he set apart a portion of his wealth to build and maintain twenty almshouses, and a free-school at Seven-oaks. In Elizabeth's reign, the school was named 'Queen Elizabeth's Grammar School,' and received a common seal for its use. It still exists, and possesses six exhibitions wherewith to reward its scholars.] Sir Thomas White, merchant-tailor, lived in the days of Queen Mary. He says he cannot speak of arms and blood-red wars: My deeds have tongues to speak, though I surcease, My orators the learned strive to be, Because I twined palms in time of peace, And gave such gifts that made fair learning free; My care did build these bowers of sweet content, Where many wise their golden times have spent. The English cities and incorporate towns Do bear me witness of my country's care; Where yearly I do feed the poor with crowns, For I was never niggard yet to spare; And all chief boroughs of this blessed land, Have somewhat tasted of my liberal hand. Sir John Bonham's life seems not to have lacked excitement. Born of gentle parents, he was apprenticed to a mercer, and shewed such qualities that he was intrusted with a valuable cargo of merchandise for the Danish market. He was received at the court of Denmark, and there made such progress in the favour of the king's daughter, with whom every knight was in love, that she gave him a favour to wear in his helmet at a grand tournament They that have guiders cannot choose but run, Their mistress's eyes do learn them chivalry, With those commands these tom-nays are begun, And shivered lances in the air do fly. No more but this, there Bonham had the best, Yet list I not to vaunt how I was blest. Despite his success in arms, Bonham did not neglect business, and as soon as he had sold his cargo and refilled his ship, he made preparations for returning home. Just as he was about to leave Denmark, the Great Solyman declared war, and began to ravage the country. Bonham was offered the command of an army destined to arrest the progress of the invader; he accepted it, and soon joined issue with the foe, half of whose army: Smouldered in the dust, Lay slaughtered on the earth in gory blood; And he himself compelled to quell his lust By composition, for his people's good. Then at a parley he admired me so, He made me knight, and let his army go. The generosity of the Turk did not stop here; he loaded the new-made knight with chains of gold and costly raiment, to which the monarch he had served so well added Gifts in guerdon of his fight, And sent him into England like a knight. Our sixth Worthy rejoiced in the alliterative appellation of Christopher Croker. He was bound 'prentice to a vintner of Gracechurch Street, and, according to his own account, must have been a fascinating young fellow: My fellow-servants loved me with their hearts; My friends rejoiced to see me prosper so, And kind Doll Stodie (though for small deserts), On me vouchsafed affection to bestow. Still, Croker was not satisfied. He burned with a desire to raise his sweetheart to high estate, and when he was pressed for the army-believing his opportunity had arrived-he was proof against the arguments of his master, and the tears of his master's daughter. To France he went, and there, he says: To prove my faith unto my country's stay, And that a 'prentice, though but small esteemed, Unto the stoutest never giveth way If credit may by trial be redeemed. At Bordeaux siege, when others came too late, I was the first made entrance through the gate. When that famous campaign was ended, our brave 'prentice was one of ten thousand men chosen by the Black Prince to aid him in restoring Don Pedro to the Castilian throne; and when he returned to England, he returned a knight. Thus labour never loseth its reward, And he that seeks for honour sure shall speed. What craven mind was ever in regard? Or where consisteth manhood but in deed? I speak it that confirmed it by my life, And in the end, Doll Stodie was my wife. Sir John Hawkwood was born to prove it does not always take nine tailors to make a man. His conduct in action won the notice of the Black Prince, who gave him a noble steed; and he made such good use of the gift, that he was knighted by that great captain, and enrolled among 'the Black Prince's knights.' When there were no more battles to be fought in France, Sir John collected together a force of 15,000 Englishmen, with which he entered the service of the Duke of Milan, and immortalised himself in Italian history as 'Giovanni Acuti Cavaliero.' He afterwards fought on the side of Spain against the pope, and having acquired riches and reputation, returned to Padua to die. Like most of his co-worthies, Sir Hugh Caverley, silk-weaver, won his knighthood in France. He then went to Poland, and became renowned as a hunter, and earned the gratitude of the people by terminating the career of a monstrous boar that troubled the land. For many years he lived in honour in Poland, but ultimately left that country for France, where he died. The last of the Nine Worthies was Sir Henry Maleverer, grocer, commonly called Henry of Cornhill, who lived in the days of Henry IV. He became a crusader, and did not leave the field till he saw the Holy City regained from the infidels. He stood high in favour with the king of Jerusalem, till that monarch's ears were poisoned against him, when, to avoid death, the gallant knight was compelled. to seek a hiding-place. This he found in the neighbourhood of Jacob's Well, of which he assumed the guardianship. For my pleasure's sake I gave both knights and princes heavy strokes; The proudest did presume a draught to take Was sure to have his passport sealed with knocks. Thus lived I till my innocence was known, And then returned; the king was pensive grown, And for the wrong which he had offered me, He vowed me greater friendship than before; My false accusers lost their liberty, And next their lives, I could not challenge more. And thus with love, with honour, and with fame, I did return to London, whence I came. When the last of the Worthies thus concluded his story, Fame gently laid his head upon a soft pillow, and left him and his companions to the happiness of their sweet sleep, and enjoined Clio to give the record of their lives to the world, 'that every one might read their honourable actions, and take example by them, to follow virtue and aspire.' |