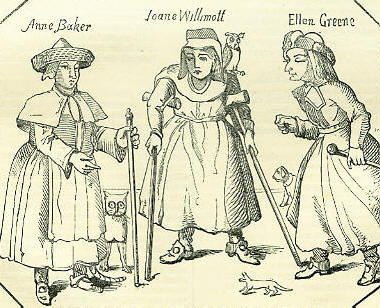

11th MarchBorn: Torquato Tasso, Italian poet, 1544, Sorrento; John Peter Niceron, French biographer, 1685, Paris; William Huskisson, statesman, 1770, Birch Moreton Court, Worcestershire. Died: John Toland, miscellaneous writer, 1722, Putney; Hannah Cowley, dramatic writer, 1809, Tiverton. Feast Day: St. Constantine, of Scotland, martyr, 6th century. St. Sophronius, Patriarch of Jerusalem, 639. St. Angus, the Culdee, bishop in Ireland, 824. St. Eulogius, of Cordova, 859. THE WITCHES OF BELVOIROn the 11th of March 1618-19, two women named Margaret and Philippa Flower, were burnt at Lincoln for the alleged crime of witch-craft. With their mother, Joan Flower, they had been confidential servants of the Earl and Countess of Rutland, at Belvoir Castle. Dissatisfaction with their employers seems to have gradually seduced these three women into the practice of hidden arts in order to obtain revenge. According to their own confession, they had entered into communion with familiar spirits, by which they were assisted in their wicked designs. Joan Flower, the mother, had hers in the bodily form of a cat, which she called Rutterkin. They used to get the hair of a member of the family and burn it: they would steal one of his gloves and plunge it in boiling water, or rub it on the back of Rutterkin, in order to effect bodily harm to its owner. They would also use frightful imprecations of wrath and malice towards the objects of their hatred. In these ways they were believed to have accomplished the death of Lord Ross, the Earl of Rutland's son, besides inflicting frightful sicknesses upon other members of the family. It was long before the earl and countess, who were an amiable couple, suspected any harm in these servants, although we are told that for some years there was a manifest change in the countenance of the mother, a diabolic expression being assumed. At length, at Christmas, 1618, the noble pair became convinced that they were the victims of a hellish plot, and the three women were apprehended, taken to Lincoln jail, and examined. The mother loudly protested innocence, and, calling for bread and butter, wished it might choke her if she were guilty of the offences laid to her charge. Immediately, taking a piece into her mouth, she fell down dead, probably, as we may allowably conjecture, overpowered by consciousness of the contrariety between these protestations and the guilty design which she had entertained in her mind. Margaret Flower, on being examined, acknowledged that she had stolen the glove of the young heir of the family, and given it to her mother, who stroked Rutterkin with it, dipped it in hot water, and pricked it: whereupon Lord Ross fell ill and suffered extremely. In order to prevent Lord and Lady Rutland from having any more children, they had taken some feathers from their bed, and a pair of gloves, which they boiled in water, mingled with a little blood. In all these particulars, Philippa corroborated her sister. Both women admitted that they had familiar spirits, which came and sucked them at various parts of their bodies: and they also described visions of devils in various forms which they had had from time to time. Associated with the Flowers in their horrible practices were three other women, of the like grade in life,-Anne Baker, of Bottesford: Joan Willimot, of Goodby: and Ellen Greene, of Stathorne, all in the county of Leicester, whose confessions were to much the same purpose. Each had her own familiar spirits to assist in working out her malignant designs against her neighbours. That of Joan Willimot was called Pretty. It had been blown into her mouth by her master, William Berry, in the form of a fairy, and immediately after came forth again and stood on the floor in the shape of a woman, to whom she forthwith promised that her soul should be enlisted in the infernal service. On one occasion, at Joan Flower's house, she saw two spirits, one like an owl, the other like a rat, one of which sucked her under the ear. This woman, however, protested that, for her part, she only employed her spirit in inquiring after the health of persons whom she had undertaken to cure. Greene confessed to having had a meeting with Willimot in the woods, when the latter called two spirits into their company, one like a kitten, the other like a mole, which, on her being left alone, mounted on her shoulders and sucked her under the ears. She had then sent them to bewitch a man and woman who had reviled her, and who, accordingly, died within a fortnight. Anne Baker seems to have been more of a visionary than any of the rest. She once saw a hand, and heard a voice from the air: she had been visited with a flash of fire: all of them ordinary occurrences in the annals of hallucination. She also had a spirit, but, as she alleged, a beneficent one, in the form of a white dog.  From the frontispiece of a contemporary pamphlet giving an account of this group of witches, we transfer a homely picture of Baker, Willimot, and Greene, attended each by her familiar spirit. The entire publication is reprinted in Nichols's Leicestershire. The examinations of these wretched women were taken by magistrates of rank and credit, and when the judges came to Lincoln the two surviving Flowers were duly tried, and on their own confessions condemned to death by the Chief Justice of the Common Pleas, Sir Henry Hobbert. THE FIRST DAILY PAPERThe British journal entitled to this description was The Daily Courant, commenced on the 11th of March 1702, by 'E. Mallet, against the Ditch at Fleet Bridge,' a site, we presume, very near that of the present Times' office, It was a single page of two columns, and professed solely to give foreign news, the editor or publisher further assuring his readers that he would not take upon himself to give any comments of his own, supposing other people to have sense enough to make reflections for themselves.' The Daily Courant very soon passed into the hands of Samuel Buckley, 'at the sign of the Dolphin in Little Britain,'-a publisher of some literary attainments, who afterwards became the printer of the Spectator, and pursued on the whole a useful and respectable career. As a curious trait of the practices of the government of Joan George I, we have Buckley entered in a list persons laid before a Secretary of State (1724), as 'Buckley, Amen-corner, the worthy printer of the Gazette-well-affected:' i.e. well-affected to the Hanover succession, a point of immense consequence at that epoch. The Daily Courant was in 1735 absorbed in the Daily Gazetteer. THE LUDDITESWho makes the quartern-loaf and Luddites rise? March 11th, 1811, is a black-letter day in the annals of Nottinghamshire. It witnessed the commencement of a series of riots which, extending over a period of five years, have, perhaps, no parallel in the history of a civilized country for the skill and secrecy with which they were managed, and the amount of wanton mischief they inflicted. The hosiery trade, which employed a large part of the population, had been for some time previously in a very depressed state. This naturally brought with it a reduction in the price of labour.During the month of February 1811, numerous bands of distressed framework-knitters were employed to sweep the streets for a paltry sum, to keep the men employed, and to prevent mischief. But by the 11th of March their patience was exhausted: and flocking to the market-place from town and country, they resolved to take vengeance on those employers who had reduced their wages. The timely appearance of the military prevented any violence in the town, but at night no fewer than sixty-three frames were broken at Arnold, a village four miles north of Nottingham. During the succeeding three weeks 200 other stocking frames were smashed by midnight bands of distressed and deluded workmen, who were so bound together by illegal oaths, and so completely disguised, that very few of them could be brought to justice. These depredators assumed the name of Luddites; said to have been derived from a youth named Ludlam, who, when his father, a framework-knitter in Leicestershire, ordered him to 'square his needles,' took his hammer and beat them into a heap. Their plan of operation was to assemble in parties of from six to sixty, as circumstances required, under a leader styled General or Ned Ladd, all disguised, and armed, some with swords, pistols, or firelocks, others with hammers and axes. They then proceeded to the scene of destruction. Those with swords and firearms were placed as a guard outside, while the others broke into the house and demolished the frames, after which they reassembled at a short distance. The leader then called over his men, who answered not to names, but to certain numbers: if all were there, and their work for the night finished, a pistol was fired, and they then departed to their homes, removing the black handkerchiefs which had covered their faces. In consequence of the continuance of these daring outrages, a large military force was brought into the neighbourhood, and two of the London police magistrates, with several other officers, came down to Nottingham, to assist the civil power in attempting to discover the ringleaders: a secret committee was also formed, and supplied with a large sum of money for the purpose of obtaining private information; but in spite of this vigilance, and in contempt of a Royal Proclamation, the offenders continued their devastations with redoubled violence, as the following instances will shew. On Sunday night, November 10th, a party of Luddites proceeded to the village of Bulwell, to destroy the frames of Mr. Rollingworth, who, in anticipation of their visit, had procured the assistance of three or four friends, who with firearms resolved to protect the property. Many shots were fired, and one of the assailants, John Woolley, of Arnold, was mortally wounded, which so enraged the mob that they soon forced an entrance: the little garrison fled, and the rioters not only destroyed the frames, but every article of furniture in the house. On the succeeding day they seized and broke a waggonload of frames near Arnold: and on the Wednesday following proceeded to Sutton-in-Ashfield, where they destroyed thirty-seven frames: after which they were dispersed by the military, who took a number of prisoners, four of whom were fully committed for trial. During the following week only one frame was destroyed, but several slacks were burned, most probably, as was supposed, by the Luddites, in revenge against the owners, who, as members of the yeoman cavalry, were active in suppressing the riots. On Sunday night, the 24th of November, thirty-four frames were demolished at Basford, and eleven more the following day. On December the 6th, the magistrates published an edict, which ordered all persons in the disturbed districts to remain in their houses after ten o'clock at night, and all public-houses to be closed at the same hour. Notwithstanding this proclamation, and a great civil and military force, thirty-six frames were broken in the villages around Nottingham within the six following days. A Royal Proclamation was then issued, offering £50 reward for the apprehension of any of the of-fenders: but this only excited the men to further deeds of daring. They now began to plunder the farmhouses both of money and provisions, declaring that they 'would not starve whilst there was plenty in the land.' In the month of January 1812, the frame-breaking continued with unabated violence. On the 30th of this month, in the three parishes of Nottingham, no fewer than 4,348 families, numbering 15,350 individuals, or nearly half the population, were relieved out of the poor rates. A large subscription was now raised to offer more liberal rewards against the perpetrators of these daring outrages: and at the March assize seven of them were sentenced to transportation. In this month, also, an Act of Parliament was passed, making it death to break a stocking or a lace frame. In April, a Mr. Trentham, a considerable manufacturer, was shot by two ruffians while standing at his own door. Happily the wound did not prove mortal: but the offenders were never brought to justice, though a reward of £600 was offered for their apprehension. This evil and destructive spirit continued to manifest itself from time to time till October 1816, when it finally ceased. Upwards of a thousand stocking frames and a number of lace machines were destroyed by it in the county of Nottingham alone, and at times it spread into the neighbouring counties of Leicester, Derby, and York, and even as far as Lancaster. Its votaries discovered at last that they were injuring themselves as much or more than their employers, as the mischief they perpetrated had to be made good out of the county rate. BITING THE THUMBIn Romeo and Juliet the servants of Capulet and Montague commence a quarrel by one biting his thumb, apparently as an insult to the others. And the commentators, considering the act of biting the thumb as an insulting gesture, quote the following passage from Decker's Dead Term in support of that opinion: -'What swearing is there' (says Decker, describing the groups that daily frequented the walks of St. Paul's Church), 'what shouldering, what jostling, what jeering, what biting of thumbs to beget quarrels I' Sir Walter Scott, referring to this subject in a note to the Lay of the Last Minstrel, says: To bite the thumb or the glove seems not to have been considered, upon the Border, as a gesture of contempt, though so used by Shakespeare, but as a pledge of mortal revenge. It is yet remembered that a young gentleman of Teviotdale, on the morning after a hard drinking bout, observed that he had bitten his glove. He instantly demanded of his companions with whom he had quarrelled? and learning that he had had words with one of the party, insisted on instant satisfaction, asserting that, though he remembered nothing of the dispute, yet he never would have bitten his glove without he had received some unpardonable insult. He fell in the duel, which was fought near Selkirk in 1721 [1707]. It is very probable that the commentators are mistaken, and the act of biting the thumb was not so much a gesture of insulting contempt as a threat-a solemn promise that, at a time and place more convenient, the sword should act as the arbitrator of the quarrel: and, consequently, a direct challenge, which, by the code of honour of the period, the other party was bound to accept. The whole history of a quarrel seems to be detailed in the graphic quotation from Decker. We almost see the ruffling swashbucklers strutting up and down St. Paul's-walk, full of braggadocio, and 'new-turned oaths.' At first they shoulder, as if by accident: at the next turn they jostle: fiery expostulation is answered by jeering, and then, but not till then, the thumb is bitten, expressive of dire revenge at a convenient opportunity, for fight they dare not within the precincts of the cathedral church. A curious illustration of this subject will be found in the following extract from evidence given at a court-martial held on a sergeant of Sir James Montgomery's regiment, in 1642. It may be necessary to state that, though the regiment was nominally raised in Ireland, all the officers and men were Scotch by birth, or the immediate descendants of Scottish settlers in Ulster. Sergeant Kyle was accused of killing Lieutenant Baird: and one of the witnesses deposed as: The witness and James McCullogh going to drink together a little after nightfall on the twenty-second of February, the said lieutenant and sergeant ran into the room where they were drinking, and the sergeant being first there, offered the chair he sat on to the lieutenant, but the lieutenant refused it, and sat upon the end of a chest. Afterwards, the lieutenant and sergeant fell a-jeering one another, upon which the sergeant told the lieutenant that if he would try him, he would find him a man, if he had aught to say to him. Also, Sergeant Kyle threw down his glove, saying there is my glove, lieutenant, unto which the lieutenant said nothing. Afterwards, many ill words were (exchanged) between them, and the lieutenant threatening him (the said sergeant), the sergeant told him that he would defend himself, and take no disgrace at his hands, but that he was not his equal, he being his inferior in place, he being a lieutenant and the said Kyle a sergeant. Afterwards the sergeant threw down his glove a second time, and the lieutenant not having a glove, demanded. James McCullogh his glove to throw to the sergeant, who would not give him his glove: upon that, the lieutenant held up his thumb licking on it with his tongue, and saying, 'There is any parole for it.' Afterwards, Sergeant Kyle went to the lieutenant's ear, and asked him, 'When?' The lieutenant answered, 'Presently.' Upon that Sergeant Kyle went out, and the lieutenant followed with his sword drawn under his arm, and being a space distant from the house said, 'Where is the villain now?' 'Here I am for you,' said Kyle, and so they struck fiercely one at another. Licking of the thumb-and why not biting?-is a most ancient form of giving a solemn pledge or promise, and has remained to a late period in Scotland as a legalized form of undertaking, or bargain. Erskine, in his Institutes, says it was 'a symbol anciently used in proof that a sale was perfected; which continues to this day in bargains of lesser importance among the lower ranks of the people-the parties licking and joining of thumbs: and decrees are yet extant, sustaining sales upon 'summones of thumb-licking,' upon this, 'That the parties had licked thumbs at finishing the bargain.'' Proverbs and snatches of Scottish song may be cited as illustrative of this ancient custom; and in the parts of Ulster where the inhabitants are of Scottish descent, it is still a common saying, when two persons have a community of opinion on any subject, ' We may lick thooms upo' that.' Jamieson, in his Scottish Dictionary, remarks: This custom, though now apparently credulous and childish, bears indubitable marks of great antiquity. Tacitus, in his Annals, states that it existed. among the Iberians: and Ihre alludes to it as a custom among the Goths. I am well assured by a gentleman, who has long resided in India, that the Moors, when concluding a bargain, do it, in the very same manner as the vulgar in Scotland, by licking their thumbs.' According to Ducange, in the mediaeval period the thumb pressed on the wax was recognised as a seal to the most important documents, and secretaries detected in forging or falsifying documents were condemned to have their thumbs cut off. The same author gives an account of a northern princess who had entered a convent and became a nun. Subsequently, circumstances occurred which rendered it an important point of high policy that she should be married, and a dispensation was obtained from Rome, abrogating her conventual vow, for that purpose. The lady, however, obstinately refused to leave her convent, and marry the husband which state policy had provided for her, so arrangements were made for marrying her by force. But the nun, placing her right thumb on the blade of a sword, swore that she would never marry, and as an oath of this solemn character could not be broken, she was allowed to remain in her convent. Hence it appears that a vow made with the thumb on a sword blade was considered more binding than that on taking the veil: and that, though the Pope could grant a dispensation for the latter, he could not or would not give one for the former. Something of the same kind prevailed among the Romans: and the Latin word polliceri-to promise, to engage-has by many been considered to be derived from pollex-pollicis, the thumb. THE BUTCHERS' SERENADEHogarth, in his delineation of the Marriage of the Industrious Apprentice to his master's daughter, takes occasion to introduce a set of butchers coming forward with marrowbones and cleavers, and roughly pushing aside those who doubtless considered themselves as the legitimate musicians. We are thus favoured with a memorial of what might be called one of the old institutions of the London vulgar-one just about to expire, and which has, in reality, become obsolete in the greater part of the metropolis. The custom in question was one essentially connected with marriage. The performers were the butchers' men,-' the bonny boys that wear the sleeves of blue.' A set of these lads, having duly accomplished themselves for the purpose, made a point of attending in front of a house containing a marriage party, with their cleavers, and each provided with a marrowbone, where-with to perform a sort of rude serenade, of course with the expectation of a fee in requital of their music. Sometimes, the group would consist of four, the cleaver of each ground to the production of a certain note; but a full band-one entitled to the highest grade of reward-would be not less than eight, producing a complete octave: and, where there was a fair skill, this series of notes would have all the fine effect of a peal of bells. When this serenade happened in the evening, the men would be dressed neatly in clean blue aprons, each with a portentous wedding favour of white paper in his breast or hat. It was wonderful with what quickness and certainty, under the enticing presentiment of beer, the serenaders got wind of a coming marriage, and with what tenacity of purpose they would go on with their performance until the expected crown or half-crown was forthcoming. The men of Clare Market were reputed to be the best performers, and their guerdon was always on the highest scale accordingly. A merry rough affair it was: troublesome somewhat to the police, and not always relished by the party for whose honour it was designed: and sometimes, when a musical band came upon the ground at the same time, or a set of boys would please to interfere with pebbles rattling in tin canisters, thus throwing a sort of burlesque on the performance, a few blows would be interchanged. Yet the Marrowbone-and-Cleaver epithalamium seldom failed to diffuse a good humour throughout the neighbourhood; and one cannot but regret that it is rapidly passing among the things that were. |