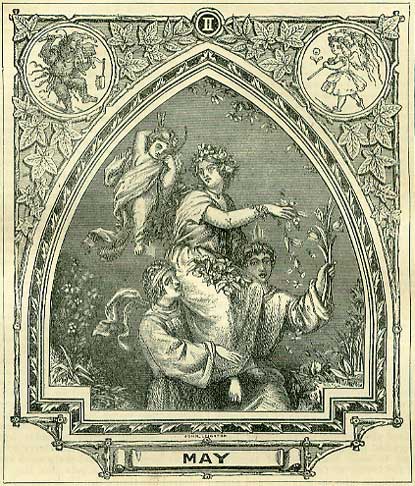

May Then came fair May, the fayrest mayd on ground, Deckt all with dainties of her season's pryde, And throwing flowres out of her lap around Upon two brethren's shoulders she did ride, The twinnes of Leda ; which on either side Supported her, like to their soveraine queene. Lord ! how all creatures laught, when her they spide, And leapt and daunc't as they had ravisht beene And Cupid selfe about her fluttered all in greene. DESCRIPTIVEMay brings with her the beauty and fragrance of hawthorn blossoms and the song of the nightingale. Our old poets delighted in describing her as a beautiful maiden, clothed in sunshine, and scattering flowers on the earth, while she danced to the music of birds and brooks. She has given a rich greenness to the young corn, and the grass is now tall enough for the flowers to play at hide-and-seek among, as they are chased by the wind. The grass also gives a softness to the dazzling white of the daisies and the glittering gold of the buttercups, which, but for this soft bordering of green, would almost be too lustrous to look upon. We hear the song of the milkmaid in the early morning, and catch glimpses of the white milk pail she balances on her head between the openings in the hedge-rows, or watch her as she paces through the fields, with her gown drawn through the pocket-hole of her quilted petticoat, to prevent it draggling in the dew. We see the dim figure of the angler, clad in grey, moving through the white mist that still lingers beside the river. The early schoolboy, who has a long way to go, loiters, and lays down his books to peep under almost every hedge and bush he passes, in quest of birds' nests. The village girl, sent on some morning errand, with the curtain of her cotton-covered bonnet hanging down her neck, 'buttons up' her little eyes to look at us, as she faces the sun, or shades her forehead with her hand, as she watches the skylark soaring and singing on its way to the great silver pavilion of clouds that stands amid the blue plains of heaven. We see the progress spring has made in the cottage gardens which we pass, for the broad-leaved rhubarb has now grown tall; the radishes are rough-leaved; the young onions show like strong grass; the rows of spinach are ready to cut, peas and young potatoes are hoed up, and the gooseberries and currants show like green beads on the bushes, while the cabbages, to the great joy of the cottagers, are beginning to 'heart.' The fields and woods now ring with incessant sounds all day long; from out the sky comes the loud cawing of the rook as it passes overhead, sometimes startling us by its sudden cry, when flying so low we can trace its moving shadow over the grass. We hear the cooing of ringdoves, and when they cease for a few moments, the pause is filled up by the singing of so many birds, that only a practised ear is enabled to distinguish one from the other; then comes the clear, bell-like note of the cuckoo, high above all, followed by the shriek of the beautifully marked jay, until it is drowned in the louder cry of the woodpecker, which some naturalists have compared to a laugh, as if the bird were a cynic, making a mockery of the whole of this grand, wild concert. In the rich green pastures there are sounds of pleasant life: the bleating of sheep, and the musical jingling of their bells, as they move along to some fresh patch of tempting herbage; the lowing of full-uddered cows, that morning and night brim the milk pails, and make much extra labour in the dairy, where the rosycheeked maidens sing merrily over their pleasant work. We see the great farm-house in the centre of the rich milk-yielding meadows, and think of cooling curds and whey, luscious cheesecakes and custards, cream that you might cut, and straw-berries growing in rows before the beehives in the garden, and we go along licking our lips at the fancied taste, and thinking how these pleasant dainties lose all their fine country flavour when brought into our smoky cities, while here they seem as if: Cool'd a long age in the deep-delved earth, Tasting of Flora and the country green. Every way bees are now flying across our path, after making ' war among the velvet buds,' out of which they come covered with pollen, as if they had been plundering some golden treasury, and were returning home with their spoils. They, with their luminous eyes-which can see in the dark-are familiar with all the little inhabitants of the flowers they plunder, and which are only visible to us through glasses that magnify largely. What a commotion a bee must make among those tiny dwellers in the golden courts of stamens and pistils, as its great eyes come peeping down into the very bottom of the calyx-the foundation of their flowery tower. Then, as we walk along, we remember that in those undated histories called the Welsh triads-which were oral traditions ages before the Romans landed on our shores-England was called the Island of Honey by its first discoverers, and that there was a pleasant murmur of bees in our primeval forests long before a human sound had disturbed their silence. But, beyond all other objects that please the eye with their beauty, and delight the sense with their fragrance, stand the May-buds, only seen in perfection at the end of this pleasant month, or a few brief days beyond. All our old poets have done reverence to the milk-white scented blossoms of the hawthorn-the May of poetry-which throws an undying fragrance over their pages; nor does any country in the world present so beautiful a sight as our long leagues of English hedgerows sheeted with May blossoms. We see it in the cottage windows, the fireless grates of clean country parlours are ornamented with it, and rarely does anyone return home without bringing back a branch of May, for there is an old household aroma in its bloom which has been familiar to them from childhood, and which they love to inhale better than any other that floats around their breezy homesteads. The refreshing smell of May-buds after a shower is a delight never to be forgotten; and, for aught we know to the contrary, birds may, like us, enjoy this delicious perfume, and we have fancied that this is why they prefer building their nests and rearing their young among the May blossoms. The red May, which is a common ornament of pleasure-grounds, derives its ruddy hue from having grown in a deep red clayey soil, and is not, we fancy, so fragrant as the white hawthorn, nor so beautiful as the pale pink May, which is coloured like the maiden blush rose. It is in the dew they shake from the pink May that our simple country maidens love to bathe their faces, believing that it will give them the complexion of the warm pearly May blossoms, which they call the Lady May. What a refreshing shower-bath, when well shaken, a large hawthorn, heavy with dew, and covered with bloom, would make! The nightingale comes with its sweet music to usher in this month of flowers, and it is now generally believed that the male is the first that makes its appearance in England, and that his song increases in sweetness as the expected arrival of the female draws nearer. Nor will he shift his place, but continues to sing about the spot where he is first heard, and where she is sure to find him when she comes. We have no doubt these birds understand one another, and that the female finds her mate by his song, which was familiar to her before her arrival, and that she can distinguish his voice from all others. Could the nightingales which are said to be seen together in the countries to which they migrate be caught and marked before they return to England, this might be proved. One bird will answer another, taking up the song where the first ceases, when they are far beyond our power of hearing, as has been proved by persons placed midway, and close to the rival songsters, who have timed the intervals between, and found that, to a second, one bird began the instant the other was silent; though the distance between was too far apart for human ears to catch a note of the bird farthest from the listener, the hands which marked the seconds on the watches showed that one bird had never begun to sing until the other had ended. You may throw a stone among the foliage where the nightingale is singing, and it will only cease for a few moments, and move away a few feet, then resume its song. At the end of this month, or early in June, its nest, which is generally formed of old oak leaves, may be found, lined only with grass-a poor home for so sweet a singer, and not unlike that in which many of our sweetest poets were first cradled. As soon as the young are hatched the male ceases to sing, losing his voice, and making only a disagreeable croaking noise when danger is near, instead of giving utterance to the same sweet song That found a path Through the sad heart of Ruth, when, sick for home, She stood in tears amid the alien corn. How enraptured must good old Izaak Walton have been with the song of the nightingale, when he exclaimed, 'Lord, what music bast Thou provided for the saints in heaven, when Thou affordest bad men such music on earth.' Butterflies are now darting about in every direction, here seeming to play with one another -a dozen together in places-there resting with folded wings on some flower, then setting off in that zig-zag flight which enables them to escape their pursuers, as few birds can turn sudden enough, when on the wing, to capture them. What is that liquid nourishment, we often wonder, which they suck up through their tiny probosces; is it dew, or the honey of flowers P Examine the exquisite scales of their wings through a glass, and then you will say that, poetical as many of the names are by which they are known, they are not equal to the beauty they attempt to designate. Rose-shaded, damask-dyed, garden-carpet, violet-spotted, green-veined, and many another name beside, conveys no notion of the jewels of gold and silver, and richly-coloured precious stones, set in the forms of the most beautiful flowers, which adorn their wings, heads, and the under part of their bodies, some portions of which appear like plumes of the gaudiest feathers. Our old poet Spenser calls the butterfly ' Lord of all the works of Nature,' who reigns over the air and earth, and feeds on flowers, taking 'Whatever thing cloth please the eye.' What a poor name is Red Admiral for that beautiful and well-known butterfly which may be driven out of almost any bed of nettles, and is richly banded with black, scarlet, and blue! Very few of these short-lived beauties survive the winter; such as do, come out with a sad, tattered appearance on the following spring, and with all their rich colours faded. By the end of this month most of the trees will have donned their new attire, nor will they ever appear more beautiful than now, for the foliage of summer is darker; the delicate spring-green is gone by the end of June, and the leaves then no longer look fresh and new. Nor is the foliage as yet dense enough to hide the traces of the branches, which, like graceful maidens, still show their shapes through their slender attire-a beauty that will be lost when they attain the full-bourgeoned matronliness of summer. But trees are rarely to be seen to perfection in woods or forests, unless it be here and there one or two standing in some open space, for in these places they are generally too crowded together. When near, if not over close, they show best in some noble avenue, especially if each tree has plenty of room to stretch out its arms, without too closely elbowing its neighbour; then a good many together can be taken in by the eye at once, from the root to the highest spray, and grand do they look as the aisle of some noble cathedral. In clumps they are 'beautiful exceedingly,' scattered as it were at random, when no separate branch is seen, but all the foliage is massed together like one immense tree, resting on its background of sky. Even on level ground a clump of trees has a pleasing appearance, for the lower branches blend harmoniously with the grass, while the blue air seems to float about the upper portions like a transparent veil. Here, too, we see such colours as only a few of our first-rate artists succeed in imitating; the sun-shine that falls golden here, and deepens into amber there, touched with bronze, then the dark green, almost black in the shade, with dashes of purple and emerald-green as the first sward of showery April. We have often fancied, when standing on some eminence that overlooked a wide stretch of woodland, we have seen such terraces along the sweeps of foliage as were too beautiful for anything excepting angels to walk upon. While thus walking and musing through the fields and woods at this pleasant season of the year, a contented and imaginative man can readily fancy that all these quiet paths and delightful prospects were made for him, or that he is a principal shareholder in Nature's great freehold. He stops in winter to see the hedger and ditcher at work, or to look at the men repairing the road, and it gives him as much pleasure to see the unsightly gap filled up with young quicksets,' the ditch embankment repaired, and the hole in the high road made sound, as it does the wealthy owner of the estate, who has to pay the men thus employed for their labour. And when he passes that way again, he stops to see how much the quicksets have grown, or whether the patch on the embankment is covered with grass and wild flowers, or if the repaired hollow in the road is sound, and has stood the drying winds of March, the heavy rains of April, and is glad to find it standing level and hard in the sunshine of May. If it is a large enclosed park, and the proprietor has put up warnings that within there are steel traps, spring guns, and ' most biting laws' for trespassers, still the contented wanderer is sure to find some gentle eminence that overlooks at least a portion of it. From this he will catch glimpses of glen and glade, and see the deer trooping through the long avenues, standing under some broad-branched oak, or, with their high antlers only visible, couching among the cool fan-leaved fern. They cannot prosecute him for looking through the great iron gates, which are aptly mounted with grim stone griffins, who ever stand rampant on the tall pillars, and seem to threaten with their dead eyes every intruder, nor prevent him from admiring the long high avenue of ancient elms, through which the sunshine streams and quivers on the broad carriage way as if it were canopied with a waving network of gold. He sees the great lake glimmering far down, and making a light behind the perspective of dark branches, and knows that those moving specks of silver which are ever crossing his vision are the stately swans sailing to and fro; the cawing of rooks falls with a pleasant sound upon his ear, as they hover around the old ancestral trees, which have been a rookery for centuries. Once there were pleasant footpaths between those aged oaks, and beside those old hawthorns-still covered with May-buds-that led to neighbouring villages, which can only now be reached by circuitous roads, that lie without the park: alas, that no 'village Hampden' rose up to do battle for the preservation of the old rights of way! Here and there an old stile, which forms a picturesque object between the heavy trunks to which it was clamped, is allowed to remain, and that is almost all there is left to point out the pleasant places through which those obliterated footpaths went winding along. We have now a great increase of flowers, and amongst them the graceful wood-sorrel-the true Irish shamrock-the trefoil leaves of which are heart-shaped, of a bright green, and a true weather-glass, as they always shut up at the approach of rain. The petals, which are beautifully streaked with lilac, soon fade when the flower is gathered, while the leaves yield the purest oxalic acid, and are much sourer than the common sorrel. Buttercups are now abundant, and make the fields one blaze of gold, for they grow higher than the generality of our grasses, and so overtop the green that surrounds them. Children may now be seen in country lanes and suburban roads carrying them home by armfuls, heads and tails mixed together, and trailing on the ground. This common flower belongs to that large family of plants which come under the ranunculus genus, and not a better flower can be found to illustrate botany, as it is easily taken to pieces, and readily explained; the number five being that of the sepals of calyx, petals, and nectar-cup, which a child can remember. Sweet woodroof now displays its small white flowers, and those who delight in perfuming their ward-robes will not fail to gather it, for it has the smell of new hay, and retains its scent a length of time, and is by many greatly preferred before lavender. This delightful fragrance is hardly perceptible when the plant is first gathered, unless the leaves are bruised or rubbed between the fingers; then the powerful odour is inhaled. The sweet woodroof is rather a scarce plant, and must be sought for in woods, about the trunks of oaks-oak-leaf mould being the soil it most delights in; though small, the white flowers are as beautiful as those of the star-shaped jessamine. Plentiful as red and white campions are, it is very rare to find them both together, though there is hardly a hedge in a sunny spot under which they are not now in bloom. Like the ragged robin, they are in many places still called cuckoo-flowers, and what the 'cuckoo buds of yellow hue' are, mentioned by Shakspere, has never been satisfactorily explained. We have little doubt, when the names of flowers two or three centuries ago were known to but few, that many which bloomed about the time the cuckoo appeared, were called cuckoo-flowers; we can find at least a score bearing that name in our old herbals. Few, when looking at the greater stitchwort, now in flower, would fancy that that large-shaped bloom was one of the family of chickweeds; as for the lesser stitchwort, it is rarely found excepting in wild wastes, where gorse and heather abound; and we almost wonder why so white and delicate a flower should choose the wilderness to flourish in, and never be found in perfection but in lonely places. Several of the beautiful wild geraniums, commonly called crane's-bill, dove's-bill, and other names, are now in flower, and some of them bear foliage as soft and downy as those that are cultivated. Some have rich rose-coloured flowers, others are dashed with deep purple, like the heart's-ease, while the one known as herb Robert is as beautiful as any of our garden flowers. But it would make a long catalogue only to give the names of all these beautiful wild geraniums which are found in flower in May. But the most curious of all plants now in bloom are the orchises, some of which look like bees, flies, spiders, and butterflies; for when in bloom you might, at a distance, fancy that each plant was covered with the insects after which it is named. An orchis has only once to be seen, and the eye is for ever familiar with the whole variety, for it resembles no other flower, displaying nothing that would seem capable of forming a seed vessel, as both stamen and style are concealed. Like the violet, it has a spur, and the bloom rises from a twisted stalk. The commonest, which, is hawked about the streets of London in April, is the Early Purple, remarkable for the dark purple spots on the leaves, but it seldom lives long. Kent is the county for orchises, where several varieties may now be found in flower. 'May was the second month in the old Alban calendar, the third in that of Romulus, and the fifth in the one instituted by Numa Pompilius- a station it has held from that distant date to the present period. It consisted of twenty-two days in the Alban, and of thirty-one in Romulus's calendar; Numa deprived it of the odd day, which Julius Caesar restored, since which it has remained undisturbed.'-Brady. The most receivable account of the origin of the name of the month is that which represents it as being assigned in honour of the Majores, or Maiores, the senate in the original constitution of Rome, June being in like manner a compliment to the, Juniores, or inferior branch of the Roman legislature. The notion that it was in honour of Maia, the mother by Jupiter of the god Hermes, or Mercury, seems entirely gratuitous, and merely surmised in consequence of the resemblance of the word. Amongst our Saxon forefathers the month was called Tri-Milchi, with an understood reference to the improved condition of the cattle under benefit of the spring herbage, the cow being now able to give milk thrice a-day. It is an idea as ancient as early Roman times, stated by Ovid in his Fasti, and still prevalent in Europe, that May is an unlucky month in which to be married. CHARACTERISTICS OF MAYWhile there is a natural eagerness to hail May as a summer month-and from its position in the year it ought to be one-it is after all very much a spring month. The mean temperature of the month in the British Islands is about 54° . The cold winds of spring still more or less prevail; the east wind has generally a great hold; and sometimes there are even falls of snow within the first ten or fifteen days. On this account proverbial wisdom warns us against being too eager to regard it as a time for light clothing: Change not a clout Till May be out. At London, the sun rises on the 1st of the month at 4:36; on the 31st at 3:54; the middle day of the month being 15h. 36m. long. The sun usually enters Gemini early in the morning of the 21st. Other proverbs regarding May are as follow: - Be it weal or be it woe, Beans blow before May doth go. Come it early or come it late, In May comes the cow-quake. A swarm of bees in May Is worth a load of hay. The haddocks are good, When clipped in May flood. Mist in May, and heat in June, Make the harvest right soon. In Scotland, in parts peculiarly exposed, the east wind of May is generally felt as a very severe affliction. On this subject, however, a gentleman was once rebuked in somewhat striking terms by one abnormis sapiens. It was the late accomplished Lord Rutherford of the Edinburgh bench, who, rambling one day on the Pentland Hills, with his friend Lord. Cockburn, encountered a shepherd who was remarkable in his district for a habit of sententious talking, in which he put everything in a triple form. Lord Rutherford, conversing with the man, expressed himself in strong terms regarding the east wind, which was then blowing very keenly.' And what ails ye at the east wind?' said the shepherd. 'It is so bitterly disagreeable,' replied the judge. I wonder at you finding so much fault with it.' And pray, did you ever find any good in it? 'Oh, yes.' 'And what can you say of good for it!' inquired Lord Rutherford. 'Weel,' replied the triadist, 'it dries the yird (soil), it slockens (refreshes) the ewes, and it's God's wull.' The learned judges were silent. |