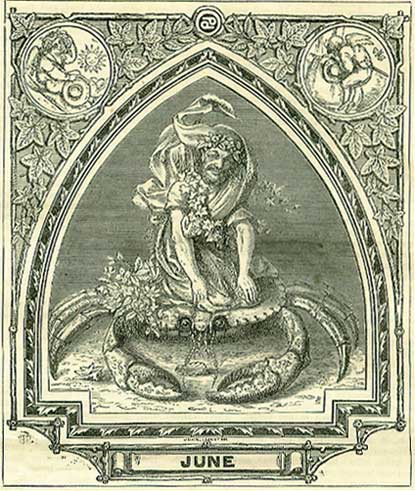

June After her came jolly June, arrayed All in green leaves, as he a player were; Yet in his time he wrought as well as played, That by his plough-irons mote right well appear. Upon a crab he rode, that did him bear, With crooked crawling steps, an uncouth pace, And backward rode, as bargemen wont to fare, Bending their force contrary to their face; Like that ungracious crew which feigns demurest grace. DESCRIPTIVEJune has now come, bending beneath her weight of roses, to ornament the halls and bowers which summer has hung with green. For this is the Month of Roses, and their beauty and fragrance conjure up again many in poetical creation which Memory had buried. We think of Herrick's Sappho, and how the roses were always white until they tried to rival her fair complexion, and, blushing for shame because they were vanquished, have ever since remained red; of Shakespeare's Juliet, musing as she leant over the balcony in the moonlight, and thinking that the rose 'by any other name would smell as sweet.' They carry us back to Chaucer's Emilie, whom we again see pacing the garden in the early morning, her hair blown backward, while, as she gathers roses carefully, she 'thrusts among the thorns her little hand.' We again see Milton's Eve in Eden, standing half-veiled in a cloud of fragrance -' so thick the blushing roses round about her blow.' This is the season to wander into the fields and woods, with a volume of sterling poetry for companion-ship, and compare the descriptive passages with the objects that lie around. We never enjoy reading portions of Spenser's Faery Queen so much as when among the great green trees in summer. We then feel his meaning, where he describes arbours that are not the work of art, 'but by the trees' own inclination made.' We look up at the great network of branches, and think how silently they have been fashioned. Through many a quiet night, and many a golden dawn, and all day long, even when the twilight threw her grey veil over them, the work advanced; from when the warp was formed of tender sprays and tiny buds, until the woof of leaves was woven with a shuttle of sunshine and showers, which the unseen wind sent in and out through the branches. No human eye could see how the work was done, for the pattern of leaves was woven motionless-here a brown bud came, and there a dot of green was thrown in; yet no hand was visible during the workmanship, though we know the great Power that stirred in that mysterious loom, and wove the green drapery of summer. Now in the woods, like a fair lady of the olden time peeping through her embowered lattice, the tall woodbine leans out from among the leaves, as if to look at the procession that is ever passing, of golden-belted bees, and gauze-winged dragon-flies, birds that dart by as if sent with hasty messages, and butterflies, the gaudy outriders, that make for themselves a pathway between the overhanging blossoms. All these she sees from the green turret in which she is imprisoned, while the bees go sounding their humming horns through every flowery town in the forest. The wild roses, compelled to obey the commands of summer, blush as they expose their beauty by the wayside, and hurry to hide themselves again amid the green when the day is done, seeming as if they tried 'to shut, and become buds again.' Like pillars of fire, the foxgloves blaze through the shadowy green of the underwood, as if to throw a light on the lesser flowers that grow around their feet. Pleasant is it now after a long walk to sit down on the slope of some hill, and gaze over the outstretched landscape, from the valley at our feet to where the river loses itself in the distant sunshine. In all those widely-spread farmhouses and cottages-some so far away that they appear but little larger than mole-hills-the busy stir of every-day life is going on, though neither sound nor motion are audible or visible from this green slope. From those quiet homes move christening, marrying, and burying processions. Thousands who have tilled the earth within the space our eye commands, ' now sleep beneath it.' There is no one living who ever saw yonder aged oak look younger that it does now. The head lies easy which erected that grey old stile, that has stood bleaching so many years in sun and wind, it looks like dried bones; the very step is worn hollow by the feet of those who have passed away for ever. How quiet yonder fields appear through which the brown footpath stretches; there those that have gone walked and talked, and played, and made love, and through them led their children by the hand, to gather the wild roses of June, that still flower as they did in those very spots where their grandfathers gathered them, when, a century back, they were children. And yet it may be that these fields, which look so beautiful in our eyes, and awaken such pleasant memories of departed summers, bring back no such remembrances to the unlettered hind; that he thinks only of the years he has toiled in them, of the hard struggle he has had to get bread for his family, and the aching bones he has gone home with at night. Perhaps, when he walks out with his children, he thinks how badly he was paid for plashing that hedge, or repairing that flowery embankment; how long it took him to plough or harrow that field; how cold the days were then, and, when his wants were greatest, what little wages he received. The flaunting woodbine may have no charms for his eye, nor the bee humming round the globe of crimson clover; perhaps he pauses not to listen to the singing of the birds, but, with eyes bent on the ground, he ' homeward plods his weary way.' Cottages buried in woodbine or covered with roses are not the haunts of peace and homes of love which poets so often picture, nor are they the gloomy abodes which some cynical politicians magnify into dens of misery. How peaceably yonder village at the foot of this hill seems to sleep in the June sunshine, beneath the overshadowing trees, above which the blue smoke ascends, nothing else seeming to stir! What rich colours some of those thatched roofs present-moss and lichen, and stonecrop which is now one blaze of gold. That white-washed wall, glimmering through the foliage, just lights up the picture where it wanted opening; even the sunlight, flashed back from the windows, lets in golden gleams through the green. That bit of brown road by the red wall, on one side of which runs the brook, spanned by a rustic bridge, is of itself a picture-with the white cow standing by the gate, where the great elder-tree is now covered with bunches of creamy-coloured bloom. Water is always beautiful in a landscape; it is the glass in which the face of heaven is mirrored, in which the trees and flowers can see themselves, for aught we know, so hidden from us in the secret of their existence and the life they live. Now, one of those out-of-door pictures may be seen which almost every landscape painter has tried to fix on canvas-that of cattle standing in water at noon-day. We always fancy they look best in a large pond overhung with trees, that is placed in a retiring corner of rich pasture lands, with their broad sweeps of grass and wild flowers. In a river or a long stream the water stretches too far away, and mars the snugness of the picture, which ought to be bordered with green, while the herd is of various colours. In a pond surrounded with trees we see the sunlight chequering the still water as it streams through the branches, while a mass of shadow lies under the lower boughs-part of it falling on a portion of the cattle, while the rest stand in a warm, green light; and should one happen to be red, and dashed with the sunlight that comes in through the leaves, it shows such flecks of ruddy gold as no artist ever yet painted. We see the shadows of the inverted trees thrown deep down, and below a blue, unfathomable depth of sky, which conjures back those ocean chasms that have never yet been sounded. We now hear that sharp rasping sound in the fields which the mower makes every time he whets his scythe, telling us that he has already cut down myriads of those beautiful wild flowers and feathered grasses which the morning sun shone upon. We enter the field, and pick a few fading flowers out "of the great swathes; and, while watching him at his work, see how at one sweep he makes a desert, where a moment before all was brightness and beauty. How one might moralize over this globe of white clover, which a bee was rifling of its sweets just before the scythe swept it down, and dwell upon the homes of ground-building birds and earth-burrowing animals and insects, which the destroyer lays bare. But these thoughts have no place in his mind. He may, while whetting his scythe, wonder how many more times he will have to sharpen it before he cuts his way up to the hedge, where his provision basket, beer bottle, and the clothes he has thrown off, lie in the shade, guarded by his dog-and when there slake his thirst. Many of those grasses which he cuts down so thoughtlessly are as beautiful as the rarest flowers that ever bloomed, though they must be examined minutely for their elegant forms and splendid colours. No plumage that ever nodded over the brow of Beauty, not even that of the rare bird of paradise, can excel the graceful silky sweep of the feather-grass, which ladies used to wear in their head-dresses. The silky bent grass, which the least stir of air sets in motion, is as glossy and beautiful as the richest satin that ever enfolded the elegant form of maidenhood. The quaking or tottering grass is hung with hundreds of beautiful spikelets, which are all shaken by the least movement of an insect's wing; and when in motion, the shifting light that plays upon its many-coloured flowers makes them glitter like jewels. But let the gentlest breeze that ever blew breathe through a bed of this beautiful grass, and you might fancy that thousands of fairy bells were swinging, and that the hair-like stems were the ropes pulled by the greenwood elves, which are thinner than the finest silk. It has many pretty names, such as pearl-grass, silk-grass; while the country children call it Ringing-all-the-bells-in-London, on account of its purple spikelets being ever in motion. Nothing was ever yet woven in loom to which art could give such graceful colouring as is shown in the luminous pink and dazzling sea-green of the soft meadow-grass; the flowers spread over a panicle of velvet bloom, which is so soft and yielding, that the lightest footed insect sinks into its downy carpeting when passing. Many grasses which the mower is now sweeping down would, to the eye of a common observer, appear all alike; though upon close examination they will be found to differ as much as one flower does from another. Amongst these are the fox-tail and other grasses,which have all round heads, and seem at the first glance only to vary in length and thickness; they are also so common, that there is hardly a field without them. We take up a handful of grass from the swathe just cut down, and find dozens of these round-headed flowers in it. One is of a rich golden green, with a covering of bright silvery hairs, so thinly interspersed, that they hide not the golden ground beneath; another is a rich purple tint, that rivals the glowing bloom of the dark-shaded pansy; while, besides colours, the stems will be found to vary, some being pointed and pinched until they resemble the limbs of a daddy-long-legs. This is the scented vernal grass, that gives out the rich aroma we now inhale from the new-mown field. It seldom grows more than a foot high, and has, as you see, a close-set panicle, just like wheat; and in these yellow dots, on the green valves that hold the flowers, the fragrance is supposed to lie which scents the June air for miles round when the grass is cut and dried. The rough, the smooth, and the annual meadow - grasses are those which everybody knows. But for the rough meadow-grass, we should not obtain so many glimpses of green as are seen in our squares and streets-for it will grow in the smokiest of cities; while to the smooth meadow-grass we are indebted for that first green flush of spring-that spring green which no dyer can imitate, and which first shows through the hoary mantle of winter. The annual meadow-grass grows wherever a pinch of earth can be found for it to root in. It is the children's garden in the damp, sunless back yards of our cities; it springs up between the stones of the pavement, and grows in the crevices of decaying walls. Neither summer suns which scorch, nor biting frosts which blacken, can destroy it; for it seeds eight or nine months of the year, and, do what you will, is sure to come up again. Pull it up you cannot, excepting in wet weather, when all the earth its countless fibres adhere to comes with it; for it finds nourishment in everything it lays hold of, nor has it, like some of the other grasses, to go far into the earth for support. In the next field we see the haymakers hard at work, turning the grass over, and shaking it up with their forks, or letting it float loose on the wind, to be blown as far as it can go; while the air that passes through it carries the pleasant smell of new-mown hay to the far away fields and villages it sweeps by. How happy hay-makers always appear, as if work to them were pleasure; even the little children, while they laugh as they throw hay over one another, are unconsciously assisting the labourers, for it cannot be dispersed too much. What a blessing it would be if all labour could be made so pleasant! Some are gathering the hay into windrows, great long unbroken ridges, that extend from one end of the field to the other, and look like motion-less waves in the distance, while between them all the space is raked up tidily. Then comes the last process, to roll those long windrows into haycocks, turning the hay on their forks over and over, and clearing the ground at every turn, as boys do the huge snowball, which it takes four or five of them to move-until the haycock is as high as a man's head, and not a vestige of a windrow is left when the work is finished by the rakers. Rolling those huge haycocks together is hard work; and when you see it done, you marvel not at the quantity of beer the men drink, labouring as they do in the hot open sunshine of June. We then see the loaded hay wagons leaving the fields, rocking as they cross the furrows, over which wheels but rarely roll, moving along green lanes and between high hedgerows, which take toll from the wains as they pass, until new hay hangs down from every branch. What labour it would save the birds in building, if hay was led two or three months earlier, for nothing could be more soft and downy for the lining of' their nests than many of the feathered heads of those dried grasses. Onward moves the rocking wagon towards the rick-yard, where the gate stands open, and we can see the men on the half-formed stack waiting for the coming load. When the stack is nearly finished, only a strong man can pitch up a fork full of hay; and it needs some practice to use the long forks which are required when the rick has nearly reached to its fullest height. What a delicious smell of new-mown hay there will be in every room of that old farmhouse for days after the stacks are finished; we almost long to take up our lodging there for a week or two for the sake of the fragrance. And there, in the 'home close,' as it is called, sits the milkmaid on her three-legged stool, which she hides somewhere under the hedge, that she may not have to carry it to and fro every time she goes to milk, talking to her cow while she is milking as if it understood her: for the flies make it restless, and she is fearful that it may kick over the contents of her pail. Now she breaks forth into song-unconscious that she is overheard-the burthen of which is that her lover may be true, ending with a wish that she were a linnet, 'to sing her love to rest,' which he, wearied with his day's labour, will not require, but will begin to snore a minute after his tired head presses the pillow. But we cannot leave the milkmaid, surrounded with the smell of new-mown hay, without taking a final glance at the grasses; and when we state that there are already upwards of two thousand varieties known and named, and that the discoveries of every year continue to add to the number, it will be seen-that the space of a large volume would be required only to enumerate the different classes into which they are divided. The oat-like, the wheat-like, and the water-grasses, of which latter the tall common seed is the chief, are very numerous. It is from grasses that we have obtained the bread we eat, and we have now many varieties in England, growing wild, that yield small grains of excellent corn, and that could, by cultivation, be rendered as valuable as our choicest cereals. It is through being surrounded by the sea, and having so few mountain ranges to shut out the breezes, the sunshine, and the showers, that England is covered with the most beautiful grasses that are to be found in the world. The open sea wooes every wind that blows, and draws all the showers towards our old homesteads, and clothes our island with that delicious green which is the wonder and admiration of foreigners. It also feeds those flocks and herds which are our pride; for nowhere else can be seen such as those pastured on English ground. Our Saxon forefathers had no other name for grass than that we still retain, though they made many pleasant allusions to it in describing the labours of the months-such as grass-month, milk-month, mow-month, hay-month, and after-month, or the month after their hay was harvested. After-month is a word still in use, though now applied to the second crop of grass, which springs up after the hay-field has been cleared. None are fonder than Englishmen of seeing a 'bit of grass' before their doors. Look at the retired old citizen, who spent the best years of his life poring over ledgers in some half-lighted office in the neighbourhood of the Bank, how delighted he is with the little grass-plat which the window of his suburban retreat opens into. What hours he spends over it, patting it down with his spade, smoothing it with his garden-roller; stooping down until his aged back aches, while clipping it with his shears; then standing at a distance to admire it; then calling his dear old wife out to see how green and pretty it looks. It keeps him in health, for in attending to it he finds both amusement and exercise; and perhaps the happiest moments of his life are those passed in watching his grandchildren roll over it, while his married sons and daughters sit smiling by his side. Hundreds of such men, and many such spots, lie scattered beside the roads that run every way through the great metropolitan suburbs; and it is pleasant, when returning from a walk through the dusty roads of June, to peep over the low walls, or through the palisades, and see the happy groups sitting in the cool of evening by the bit of grass before their doors, and which they call 'going out on the lawn.' HISTORICALOvid, in his Fasti, makes Juno claim the honour of giving a name to this month; but there had been ample time before his day for an obscurity to invest the origin of the term, and he lived before it was the custom to investigate such matters critically. Standing as the fourth month in the Roman calendar, it was in reality dedicated a Junioribus-that is, to the junior or inferior branch of the original legislature of Rome, as May was a Majoribus, or to the superior branch. 'Romulus assigned to this month a complement of thirty days, though in the old Latin or Alban calendar it consisted of twenty-six only. Numa deprived it of one day, which was restored by Julius Caesar; since which time it has remained undisturbed.' -Brady. CHARACTERISTICS OF JUNEThough the summer solstice takes place on the 21st day, June is only the third month of the year in respect of temperature, being preceded in this respect by July and August. The mornings, in the early part of the month especially, are liable to be even frosty, to the extensive damage of the buds of the fruit-trees. Nevertheless, June is the mouth of greatest summer beauty-the month during which the trees are in their best and freshest garniture. 'The leafy month of June,' Coleridge well calls it, the month when the flowers are at the richest in hue and profusion. In English landscape, the conical clusters of the chestnut buds, and the tassels of the laburnum and lilac, vie above with the variegated show of wild flowers below. Nature is now a pretty maiden of seventeen; she may show maturer charms afterwards, but she can never be again so gaily, so freshly beautiful. Dr Aiken says justly that June is in reality, in this climate, what the poets only dream May to be. The mean temperature of the air was given by an observer in Scotland as 59° Fahrenheit, against 60° for August and 61° for July. The sun, formally speaking, reaches the most northerly point in the zodiac, and enters the constellation of Cancer, on the 21st of June; but for several days about that time there is no observable difference in his position, or his hours of rising and setting. At Greenwich he is above the horizon from 3:43 morning, to 8:17 evening, thus making a day of 16h. 26m. At Edinburgh, the longest day is about 17½ hours. At that season, in Scotland, there is a glow equal to dawn, in the north, through the whole of the brief night. The present writer was able at Edinburgh to read the title-page of a book, by the light of the northern sky, at midnight of the 14th of Juno 1849. In Shetland, the light at mid-night is like a good twilight, and the text of any ordinary book may then be easily read. It is even alleged that, by the aid of refraction, and in favourable circumstances, the body of the sun has been seen at that season, from the top of a hill in Orkney, though the fact cannot be said to be authenticated. MARRIAGE SUPERSTITIONS AND CUSTOMSwas the month which the Romans considered the most propitious season of the year for contracting matrimonial engagements, chosen were l that of the full moon or the conjunction of the sun and moon; the month of May was especially to be avoided, as under the influence of spirits adverse to happy households. All these pagan superstitions were retained in the Middle Ages, with many others which belonged more particularly to the spirit of Christianity: people then had recourse to all kinds of divination, love philters, magical invocations, prayers, fastings, and other follies, which were modified according to the country and the individual. A girl had only to agitate the water in a bucket of spring-water with her hand, or to throw broken eggs over another person's head, if she wished to see the image of the man she should marry. A union could never be happy if the bridal party, in going to church, met a monk, a priest, a hare, a dog, cat, lizard, or serpent; while all would go well if it were a wolf, a spider, or a toad. Nor was it an unimportant matter to choose the wedding day carefully; the feast of Saint Joseph was especially to be avoided, and it is supposed, that as this day fell in mid-Lent, it was the reason why all the councils and synods of the church forbade marriage during that season of fasting; indeed, all penitential days and vigils throughout the year were considered unsuitable for these joyous ceremonies. The church blamed those husbands who married early in the morning, in dirty or negligent attire, reserving their better dresses for balls and feasts; and the clergy were forbidden to celebrate the rites after sunset, because the crowd often carried the party by main force to the ale-house, or beat them and hindered their departure from the church until they had paid a ransom. The people always manifested a strong aversion for badly assorted marriages. In such cases, the procession would be accompanied to the altar in the midst of a frightful concert of bells, sauce-pans, and frying-pans, or this tumult was reserved for the night, when the happy couple were settled in their own house. The church tried in vain to defend widowers and widows who chose to enter the nuptial bonds a second time; a synodal order of the Archbishop of Lyons, in 1577, thus describes the conduct it excommunicated: ' Marching in masks, throwing poisons, horrible and dangerous liquids before the door, sounding tambourines, doing all kinds of dirty things they can think of, until they have drawn from the husband large sums of' money by force.' A considerable sum of money was anciently put into a purse or plate, and presented by the bridegroom to the bride on the wedding-night, as a sort of purchase of her person; a custom common to the Greeks as well as the Ro-mans, and which seems to have prevailed among the Jews and many Eastern nations. It was changed in the Middle Ages, and in the north of Europe, for the morgengabe, or morning present; the bride having the privilege, the morning after the wedding-day, of asking for any sum of money or any estate that she pleased, and which could not in honour be refused by her husband. The demand at times became really serious, if the wife were of an avaricious temper. Something of the same kind prevailed in England under the name of the Dow Purse. A trace of this is still kept up in Cumberland where the bridegroom provides himself with gold and crown pieces, and, when the service reaches the point, ' With all my worldly goods I thee endow,' he takes up the money, hands the clergyman his fee, and pours the rest into a handkerchief which is held by the bridesmaid for the bride. When Clovis was married to the Princess Clotilde, he offered, by his proxy, a sou and a denier, which became the marriage offering by law in France; and to this day pieces of money are given to the bride, varying only in value according to the rank of the parties. How the ring came to be used is not well ascertained, as in former days it did not occupy its present prominent position, but was given with other presents to mark the completion of a contract. Its form is intended as a symbol of eternity, and of the intention of both parties to keep for ever the solemn covenant into which they have entered before God, and of which it is a pledge. When the persons were betrothed as children, among the Anglo-Saxons, the bride-groom gave a pledge, or 'wed' (a term from which we derive the word wedding); part of this wed consisted of a ring, which was placed on the maiden's right hand, and there religiously kept until transferred to the other hand at the second ceremony. Our marriage service is very nearly the same as that used by our forefathers, a few obsolete words only being changed. The bride was taken 'for fairer, for fouler, for better, for worse;' and promised 'to be buxom and bonny' to her future husband. The bridegroom put the ring on each of the bride's left-hand fingers in turn, saying at the first, 'in the name of the Father;' at the second, 'in the name of the Son,' at the third, ' in the name of the Holy Ghost;' and at the fourth, 'Amen.' The father presented his son-in-law with one of his daughter's shoes as a token of the transfer of authority, and the bride was made to feel the change by a blow on her head given with the shoe. The husband was bound by oath to use his wife well, in failure of which she might leave him; yet as a point of honour he was allowed 'to bestow on his wife and apprentices moderate castigation.' An old Welsh law tells us that three blows with a broomstick, on any 'part of the person except the head, is a fair allowance;' and another provides that the stick be not longer than the husband's arm, nor thicker than his middle finger. An English wedding, in the time of good Queen Bess, was a joyous public festival; among the higher ranks, the bridegroom presented the company with scarves, gloves, and garters of the favourite colours of the wedding pair; and the ceremony wound up with. banquetings, masques, pageants, and epithalamiums. A gay procession formed a part of the humbler marriages; the bride was led to church between two boys wearing bride-laces and rosemary tied about their silken sleeves, and before her was carried a silver cup filled with wine, in which was a large branch of gilded rosemary, hung about with silk ribbons of all colours. Next came the musicians, and then the bridesmaids, some bearing great bridecakes, others garlands of gilded wheat; thus they marched to church amidst the shouts and benedictions of the spectators. The penny weddings, at which each of the guests gave a contribution for the feast, were reprobated by the straiter-laced sort as leading to disorders and licentiousness; but it was found impossible to suppress them. All that could be done was to place restrictions upon the amount allowed to be given; in Scotland five shillings was the limit. The customs of marrying and giving in marriage in Sweden, in former years, were of a somewhat barbarous character; it was beneath the dignity of a Scandinavian warrior to court a lady's favour by gallantry and submission-he waited until she had bestowed her affections on another, and was on her way to the marriage ceremony, when, collecting his faithful followers, who were always ready for the fight, they fell upon the wedding cortege, and the stronger carried away the bride. It was much in favour of this practice that marriages were always celebrated at night. A pile of lances is still preserved behind the altar of the ancient church of Husaby, in Gothland, into which were fitted torches, and which were borne before the bridegroom for the double purpose of giving light and protection. It was the province of the groomsmen, or, as they were named, 'best men,' to carry these; and the strongest and stoutest of the bridegroom's friends were chosen for this duty. Three or four days before the marriage, the ceremony of the bride's bath took place, when the lady went in great state to the bath, accompanied by all her friends, married and single; the day closing with a banquet and ball. On the marriage-day the young couple sat on a raised platform, under a canopy of silk; all the wedding presents being arranged on a bench covered with silk, and consisting of plate, jewels, and money. To this day the bridegroom has a great fear of the trolls and sprites which still inhabit Sweden; and, as an antidote against their power, he sews into his clothes various strong smelling herbs, such. as garlick, chives, and rosemary. The young women always carry bouquets of these in their hands to the feast, whilst they deck themselves out with loads of jewellery, gold bells, and grelots as large as small apples, with chains, belts, and stomachers. No bridegroom could be induced on that day to stand near a closed gate, or where cross roads meet; he says he takes these precautions ' against envy and malice.' On the other hand, if the bride be prudent, she will take care when at the altar to put her right foot before that of the bridegroom, for then she will get the better of her husband during her married life; she will also be studious to get the first sight of him before he can see her, because that will pre-serve her influence over him. It is customary to fill the bride's pocket with bread, which she gives to the poor she meets on her road to church, a misfortune being averted with every alms bestowed; but the beggar will not eat it, as he thereby brings wretchedness on himself. On their return from church, the bride and bridegroom must visit their cowhouses and stables, that the cattle may thrive and multiply. In Norway, the marriages of the bonder or peasantry are conducted with very gay ceremonies, and in each parish there is a set of ornaments for the temporary use of the bride, including a showy coronal and girdle; so that the poorest woman in the land has the gratification of appearing for one day in her life in a guise which she probably thinks equal to that of a queen. The museum of national antiquities at Copenhagen contains a number of such sets of bridal decorations which were formerly used in Denmark. In the International Exhibition at London, in 1862, the Norwegian court showed the model of a peasant couple, as dressed and decorated for their wedding; and every beholder must have been arrested by its homely splendours. Annexed is a cut representing the bride.  In pagan days, when Rolf married King Erik's daughter, the king and queen sat throned in state, whilst courtiers passed in front, offering gifts of oxen, cows, swine, sheep, sucking-pigs, geese, and even cats. A shield, sword, and axe were among the bride's wedding outfit, that she might, if necessary, defend herself from her husband's blows. In the vast steppes of south-eastern Russia, on the shores of the Caspian and Black Sea, marriage ceremonies recall the patriarchal customs of the earliest stages of society. The evening before the day when the affianced bride is given to her husband, she pays visits to her master and the inhabitants of the village, in the simple dress of a peasant, consisting of a red cloth jacket, descending as low as the knees, a very short white petticoat, fastened at the waist with a red woollen scarf, above which is an embroidered chemise. The legs, which are always bare above the ankle, are sometimes protected by red or yellow morocco boots. The girls of the village who accompany her are, on the contrary, attired in their best, recalling the old paintings of Byzantine art, where the Virgin is adorned with a coronal. They know how to arrange with great art the leaves and scarlet berries of various kinds of trees in their hair, the tresses of which are plaited as a crown, or hang down on the shoulders. A necklace of pearls or coral is wound at least a dozen times round the neck, on which they hang religious medals, with. enamel paintings imitating mosaic. At each house the betrothed throws herself on her knees before the head of it, and kisses his feet as she begs his pardon; the fair penitent is immediately raised and kissed, receiving some small present, whilst she in return gives a small roll of bread, of a symbolic form. On her return home all her beautiful hair is cut off, as henceforth she must wear the platoke, or turban, a woollen or linen shawl which is rolled round the head, and is the only distinction between the married and unmarried. It is invariably presented by the husband, as the Indian shawl among ourselves; which, however, we have withdrawn from its original destination, which ought only to be a head-dress. The despoiled bride expresses her regrets with touching grace, in one of their simple songs: 'Oh, my curls, my fair golden hair! Not for one only, not for two years only, have I arranged you-every Saturday you were bathed, every Sunday you were ornamented, and to-day, in a single hour, I must lose you!' The old woman whose duty it is to roll the turban round the brow, wishing her happiness, says, ' I cover your head with the platoke:, my sister, and I wish you health and happiness. Be pure as water, and fruitful as the earth.' When the marriage is over, the husband takes his wife to the inhabitants of the village, and shows them the change of dress effected the night before. Among the various tribes of Asia none are so rich or well-dressed as the Armenians; to them belongs chiefly the merchandise of precious stones, which they export to Constantinople. The Armenian girl whose marriage is to be described had delicate flowers of celestial blue painted all over her breast and neck, her eye-brows were dyed black, and the tips of her fingers and nails of a bright orange. She wore on each hand valuable rings set with precious stones, and round her neck a string of very fine turquoises; her shirt was of the finest spun silk, her jacket and trousers of cashmere of a bright colour. The priest and his deacon arrived; the latter bringing a bag containing the sacerdotal garments, in which the priest arrayed himself, placing a mitre ornamented with precious stones on his head, and a collar of metal,-on which the twelve apostles were represented in bas-relief, -round his neck. He began by blessing a sort of temporary altar in the middle of the room; the mother of the bride took her by the hand, and leading her forward, she bowed at the feet of her future husband, to show that she acknowledged him as lord and master. The priest, placing their hands in each other, pronounced a prayer, and then drew their heads together until they touched three times, while with his right hand he made a motion as if blessing them; a second time their hands were joined, and the bridegroom was asked, 'Will you be her husband?' will,' he answered, raising at the same time the veil of the bride, in token that she was now his, and letting it fall again. The priest then took two wreaths of flowers, ornamented with a quantity of hanging gold threads, from the hands of the deacon, put them on the heads of the married couple, changed them three times from one head to the other, repeating each time, 'I unite you, and bind you one to another -live in peace.' Such are the customs in the very land where man was first created; and, among nations who change so little as those in the East, we may fairly believe them to be among the most ancient. WHIT-SUNDAY WOMAN-SHOW IN RUSSIAA custom has long prevailed at St. Petersburg which can only be regarded as a relic of a rude state of society; for it is nothing more or less than a show of marriageable women or girls, with a view of obtaining husbands. The women certainly have a choice in the matter, and in this respect they are not brought to market in the same sense as fat cattle or sheep; but still it is only under the influence of a very coarse estimate of the sex that the custom can prevail. The manner of managing the show in past years was as follows. On Whit Sunday afternoon the Summer Garden, a place of popular resort in St. Petersburg, was thronged with bachelors and maidens, looking out for wives and husbands respectively. The girls put on their best adornments; and these were sometimes more costly than would seem to be suitable for persons in humble life, were it not that this kind of pride is much cherished among the peasantry in many countries. Bunches of silver tea-spoons, a large silver ladle, or some other household luxury, were in many instances held in the hand, to denote that the maiden could bring some-thing valuable to her husband. The young men, on their part, did not fail to look their best. The maidens were accompanied by their parents, or by some elder member of their family, in order that everything might be conducted in a decorous manner. The bachelors, strolling and sauntering to and fro, would notice the maidens as they passed, and the maidens would blushingly try to look their best. Supposing a young man were favourably impressed with what he saw, he did not immediately address the object of his admiration, but had a little quiet talk with one of the seniors, most probably a woman. He told her his name, residence, and occupation; ho gave a brief inventory of his worldly goods, naming the number of roubles (if any) which he had been able to save. On his side he asked questions, one of which was sure to relate to the amount of dowry promised for the maiden. The woman with whom this conversation was held was often no relative to the maiden, but a sort of marriage broker or saleswoman, who conducted these delicate negotiations, either in friendliness or for a fee. If the references on either side were unsatisfactory, the colloquy ended without any bargain being struck; and, even if favourable, nothing was immediately decided. Many admirers for the same girl might probably come forward in this way. In the evening a family conclave was held concerning the chances of each maiden, at which the offer of each bachelor was calmly considered, chiefly in relation to the question of roubles. The test was very little other than that ' the highest bidder shall be the purchaser.' A note was sent to the young man whose offer was deemed most eligible; and it was very rarely that the girl made any objection to the spouse thus selected for her. The St. Petersburg correspondent of one of the London newspapers, who was at the Woman Show on Whit Sunday, 1861, stated that the custom has been gradually declining for many years; that there were very few candidates for matrimony on that occasion; and that the total abandonment of the usage was likely soon to occur, under the influence of opinion more con-genial to the tastes of Europeans generally. CREELING THE BRIDEGROOMA curious custom in connexion with marriage prevailed at one time in Scotland, and, from the manner in which it was carried out, was called 'Creeling the Bridegroom.' The mode of procedure in the village of Galashiels was as follows. Early in the day after the marriage, those interested in the proceeding assembled at the house of the newly-wedded couple, bringing with them a 'creel,' or basket, which they filled with stones. The young husband, on being brought to the door, had the creel firmly fixed upon his back, and with it in this position had to run the round of the town, or at least the chief portion of it, followed by a number of men to see that he did not drop his burden; the only condition on which he was allowed to do so being that his wife should come after him, and kiss him. As relief depended altogether upon the wife, it would sometimes happen that the husband did not need to run more than a few yards; but when she was more than ordinarily bashful, or wished to have a little sport at the expense of her lord and master-which it may be supposed would not unfrequently be the case-he had to carry his load a considerable distance. This custom was very strictly enforced; for the person who was last creeled had charge of the ceremony, and he was naturally anxious that no one should escape. The practice, as far as Galashiels was concerned, came to an end about sixty years ago, in the person of one Robert Young, who, on the ostensible plea of a 'sore back,' lay a-bed all the day after his marriage, and obstinately refused to get up and be eroded; he had been twice married before, and no doubt felt that he had had enough of eroding. MARRIAGE LAWS AND CUSTOMS IN THE EAST OF ENGLANDThere is a saying of Hesiod's (Works and Days, 1. 700), to the effect that it is better to marry a woman from the neighbourhood, than one from a distance. With this may be compared the Scotch proverb, 'It is better to marry over the midden, than over the moor,' i.e. to take for your wife one who lives close by-the other side of the muckheap-than to fetch one from the other side of the moor. I am not aware of the existence of any proverb to this effect in East Anglia; but the usual practice of the working classes is in strict accordance with it. Whole parishes have intermarried to such an extent that almost everybody is related to, or connected with everybody else. One curious result of this is that no one is counted as a 'relation' beyond first cousins, for if 'relationship' went further than that it might almost as well include the whole parish. A very strong inducement to marry a near neighbour, lies, no doubt, in the great advantage of having a mother, aunt, or sister at hand whose help can be obtained in case of sickness; I have frequently heard complaints of the inconvenience of 'having nobody belonging to them,' made by sick people, whose near relations live at a distance, and who in consequence are obliged to call in paid help when ill. |