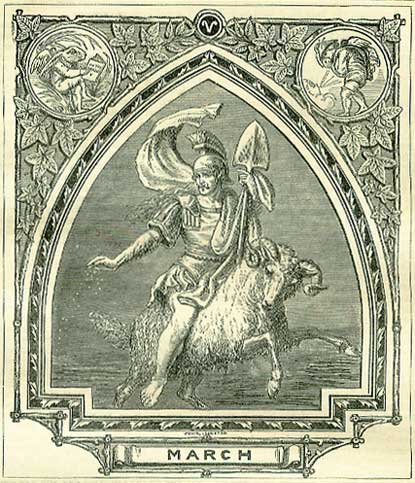

March Sturdy March, with brows full sternly bent, And armed strongly, rode upon a ram, The same which over Hellespontus swam, Yet in his hand a spade he also bent And in a bag all sorts of weeds, y same Which on the earth he strewed as he went, And filled her womb with fruitful hope of nourishment. DESCRIPTIVEMarch is the first month of Spring. He is Nature's Old Forester, going through the woods and dotting the trees with green, to mark out the spots where the future leaves are to be hung. The sun throws a golden glory over the eastern hills, as the village-clock from the ivy-covered tower tolls six, gilding the hands and the figures that were scarcely visible two hours later a few weeks ago. The streams now hurry along with a rapid motion, as if they had no time to dally with, and play round the impeding pebbles, but were eager to rush along the green meadow-lands, to tell the flowers it is time to awaken. We hear the cottagers greeting each other with kind 'Good morning,' across the paled garden-fences in the sunrise, and talking about the healthy look of the up-coming peas, and the promise in a few days of a dish of early spinach. Under the old oak, surrounded with rustic seats, they congregate on the village-green, in the mild March evenings, and talk about the forward spring, and how they have battled through the long hard winter, and, looking towards the green churchyard, speak in low voices of those who have been borne thither to sleep out their long sleep since ' last primrose-time,' and they thank God that they are still alive and well, and are grateful for the fine weather ' it has pleased Him to send them at last.' Now rustic figures move across the landscape, and give a picturesque life to the scenery. You see the ploughboy returning from his labour, seated sideways on one of his horses, humming a line or two of some lovelorn ditty, and when his memory fails to supply the words, whistling the remainder of the tune. The butcher-boy rattles merrily by in his blue-coat, throwing a saucy word to every one he passes; and if he thinks at all of the pretty lambs that are bleating in his cart, it is only about how much they will weigh when they are killed. The old woman moves slowly along in her red cloak, with basket on arm, on her way to supply her customers with new-laid eggs. So the figures move over the brown winding roads between the budding hedges in red, blue, and grey, such as a painter loves to seize upon to give light, and colour, to his landscape. A few weeks ago those roads seemed uninhabited. The early-yeaned lambs have now become strong, and may be seen playing with one another, their chief amusement being that of racing, as if they knew what heavy weights their little legs will have to bear when their feeders begin to lay as much mutton on their backs as they can well walk under-so enjoy the lightness of their young lean days. There is no cry so childlike as that of a lamb that has lost its dam, and how eagerly it sets off at the first bleat the ewe gives: in an instant it recognises that sound from all the rest, while to our ears that of the whole flock sounds alike. Dumb animals we may call them, but all of them have a language which they understand; they give utterance to their feelings of joy, love, and pain, and when in distress call for help, and, as we have witnessed, hurry to the aid of one another. The osier-peelers are now busy at work in the osier-holts; it is al most the first out-of-door employment the poor people find in spring, and very pleasant it is to see the white-peeled willows lying about to dry on the young grass, though it is cold work by a windy river side for the poor women and children on a bleak March day. As soon as the sap rises, the bark-peelers commence stripping the trees in the woods, and we know but few country smells that equal the aroma of the piled-up bark. But the trees have a strange ghastly look after they are stripped-unless they are at once removed-standing like bleached skeletons when the foliage hangs on the surrounding branches. The rumbling wagon is a pretty sight moving through the wood, between openings of the trees, piled high with bark, where wheel never passes, excepting on such occasions, or when the timber is removed. The great ground-bee, that seems to have no hive, goes blundering by, then alights on some green patch of grass in the underwood, though what he finds there to feed upon is a puzzle to you, even if you kneel down beside him, as we have done, and watch ever so narrowly. How beautiful the cloud and sunshine seem chasing each other over the tender grass! You see the patch of daisies shadowed for a few moments, then the sunshine sweeps over them, and all their silver frills seem suddenly touched with gold, which the wind sets in motion. Our forefathers well named this month 'March many-weathers,' and said that 'it came in like a lion, and went out like a lamb,' for it is made up of sunshine and cloud, shower and storm, often causing the horn-fisted ploughman to beat his hands across his chest in the morning to warm them, and before noon compelling him to throw off his smock-frock and sleeved waistcoat, and wipe the perspiration from his forehead with his shirt sleeve, as he stands between the plough-stilts at the end of the newly-made furrow. Still we can now plant our 'foot upon nine daisies,' and not until that can be done do the old-fashioned country people believe that spring is really come. We have seen a grey-haired grandsire do this, and smile as he called to his old dame to count the daisies, and see that his foot fairly covered the proper number. Ants now begin to run across our paths, and sometimes during a walk in the country you may chance to stumble upon the nest of the wood-ant. At a first glance it looks like a large heap of litter, where dead leaves and short withered grass have been thrown lightly down upon the earth; perhaps at the moment there is no sign of life about it, beyond a straggler or two at the base of the mound. Thrust in the point of your stick, and all the ground will be alive in a moment; nothing but a mass of moving ants will be seen where you have probed. Nor will it do to stay too long, for they will be under your trousers and up your boots, and you will soon feel as if scores of red-hot needles were run into you, for they wound sharply. If you want the clean skeleton of a mouse, bird, or any other small animal, throw it on the nest of the wood-ant, and on the following day you will find every bone as bare and clean as if it had been scraped. Snakes may now be seen basking in some sunny spot, generally near a water-course, for they are beautiful swimmers and fond of water. They have slept away the winter under the dead leaves, or among the roots, and in the holes of trees, or wherever they could find shelter. In ponds and ditches may also be seen thousands of round-headed long-tailed tadpoles, which, if not devoured, will soon become nimble young frogs, when they have a little better chance of escaping the jaws of fishes and wildfowl, for no end of birds, fishes, reptiles, and quadrupeds feed on them. Only a few weeks ago the frogs were in a torpid state, and sunk like stones beneath the mud. Since then they left those black spots, which may be seen floating in a jellied mass on the water, and soon from this spawn the myriads of lively tadpoles we now see sprang into life. Experienced gardeners never drive frogs out of their grounds, as they are great destroyers of slugs, which seem to be their favourite food. Amongst the tadpoles the water-rat may now be seen swimming about and nibbling at some leaf, or overhanging blade of grass, his tail acting as a rudder, by which he can steer himself into any little nook, wheresoever he may take a fancy to go. If you are near enough, you will see his rich silky hair covered with bright silver-like bubbles as they sink into the water, and he is a most graceful swimmer. The entrance to his nest is generally under the water; throw a stone and he will dive down in a moment, and when he has passed the watery basement, he at once ascends his warm dry nest, in which, on one occasion, a gallon of potatoes was found, that he had hoarded up to last him through the winter. Pleasant is it on a fine March day to stand on some rustic bridge-it may be only a plank thrown across the stream-and watch the fishes as they glide by, or pause and turn in the water, or to see the great pike basking near the surface, as if asleep in the sunshine. Occasionally a bird will dart out from the sedge, or leave off tugging at the head of the tall bulrush, and hasten away between the willows, that seem to give a silvery shiver, every time the breeze turns up the underpart of their leaves to the light. In solitary places, by deep watercourses, the solemn plunge of the otter may sometimes be heard, as he darts in after his prey, or you may start him from the bank where he is feeding on the fish he has captured. Violets, which Shakspeare says are 'sweeter than the lids of Juno's eyes,' impregnate the March winds with their fragrance, and it is amazing what a distance the perfume is borne on the air from the spot where they grow; and, but for thus betraying themselves, the places where they nestle together would not always be found. Though called the wood-violet, it is oftener found on sunny embankments, under the shelter of a hedge, than in the woods; a woodside bank that faces the south may often be seen diapered with both violets and primroses. Though it is commonly called the 'blue violet,' it approaches nearer to purple in colour. The scentless autumn violets are blue. No lady selecting a violet-coloured dress would choose a blue. The dark-velvet' is a name given to it by our old poets, who also call it 'wine-coloured;' others call the hue 'watchet,' which is blue. But let it be compared with the blue-bell, beside which it is often found, and it will appear purple in contrast. Through the frequent mention made of it by Shakspeare, it must have been one of his favourite flowers; and as it still grows abundantly in the neighbourhood of Stratford-on-Avon, it may perhaps yet be found scenting the March air, and standing in the very same spots by which he paused to look at it. Like the rose, it retains its fragrance long after the flower is dead. The perfume of violets and the song of the black-cap are delights which may often be enjoyed together while walking out at this season of the year, for the blackcap, whose song is only equalled by that of the nightingale, is one of the earliest birds that arrives. Though he is a droll-looking little fellow in his black wig, which seems too big for his head, yet, listen to him! and if you have never heard him before, you will hear such music as you would hardly think such an organ as a bird's throat could make. There is one silvery shake which no other bird can compass: it sinks down to the very lowest sound music is capable of making, and yet is as distinct as the low ring of a silver bell. The nightingale has no such note: for there is an unapproachable depth in its low sweetness. While singing, its throat is wonderfully distended, and the whole of its little body shivers with delight. Later in the season, it often builds its compact nest amid the sheltering leaves of the ivy, in which it lays four or five eggs, which are fancifully dashed with darker spots of a similar hue. Daisies, one of the earliest known of our old English flowers that still retains its Saxon name, are now in bloom. It was called the day's-eye, and the eye-of-day, as far back as we have any records of our history. 'It is such a wanderer,' says a quaint old writer, 'that it must have been one of the first flowers that strayed and grew outside the garden of Eden.' Poets have delighted to call them 'stars of the earth,' and Chaucer describes a green valley 'with daisies powdered over,' and great was his love for this beautiful flower. He tells us how he rose early in the morning, and went out again in the evening, to see the day's-eye open and shut, and that he often lay down on his side to watch it unfold. But beautiful as its silver rim looks, streaked sometimes with red, 'as if grown in the blood of our old battle-fields,' says the above-quoted writer, still it is a perfect compound flower, as one of those little yellow florets which form its 'golden boss ' or crown will show, when carefully examined. Whatever may be said of Linnaeus, Chaucer was the first who discovered that the daisy slept, for he tells us how he went out, To see this flower, how it will go to rest, For fear of night, so ha-Loth it the darkness. He also calls the opening of the daisy 'its resurrection,' so that nearly five centuries ago the sleep of plants was familiar to the Father of English Poetry. Now the nests of the black-bird and thrush may be seen in the hedges, before the leaves are fully out, for they are our earliest builders, as well as the first to awaken Winter with their songs. As if to prepare better for the cold, to which their young are ex-posed, through being hatched so soon as they are, they both plaster their nests inside with mud, until they are as smooth as a basin. They begin singing at the first break of dawn, and may be heard again as the day closes. We have frequently heard them before three in the morning in summer. The blackbird is called ' golden bill' by country people, and the 'ouzel cock' of our old ballad poetry. It is not easy to tell males from females during the first year, but in the second year the male has the 'golden bill.' If undisturbed, the blackbird will build for many seasons in the same spot, often only repairing its old nest. No young birds are more easily reared, as they will eat al most anything. Both the nests and eggs of the thrush and blackbird are much alike. Sometimes, while peeping about to discover these rounded nests, we catch sight of the germander-speedwell, one of the most beautiful of our March flowers, bearing such a blue as is only at times seen on the changing sky; we know no blue flower that can be compared with it. The ivy-leaved veronica may also now be found, though it is a very small flower, and must be sought for very near the ground. Now and then, but not always, we have found the graceful wood-anemone in flower in March, and very pleasant it is to come unaware upon a bed of these pretty plants in bloom, they shew such a play of shifting colours when stirred by the wind, now turning their reddish-purple outside to the light, then waving back again, and showing the rich white-grey inside the petals, as if white and purple lilacs were mixed, and blowing together. The leaves, too, are very beautifully cut; and as the flower has no proper calyx, the pendulous cup droops gracefully, 'hanging its head aside,' like Shakespeare's beautiful Barbara. If-through the slighte breeze setting its drooping bells in motion-the old Greeks called it the wind flower, it was happily named, for we see it stirring when there is scarce more life in the air than On a summer's day Robs not one light seed from the feathered grass.' The wheat-ear, which country children say, 'some bird blackened its eye for going away,' now makes its appearance, and is readily known by the black mark which runs from the ear to the base of the bill. Its notes are very low and sweet, for it seems too fat to strain itself, and we have no doubt could sing much louder if it pleased. It is considered so delicious a morsel, that epicures have named it the British ortolan, and is so fat it can scarcely fly when wheat is ripe. Along with it comes the pretty willow-wren, which is easily known by being yellow underneath, and through the light colour of its legs. It lives entirely on insects, never touching either bloom or fruit like the bullfinch, and is of great value in our gardens, when at this season such numbers of insects attack the blossoms. But one of the most curious of our early comers is the little wryneck, so called because he is always twisting his neck about. When boys, we only knew it by the name of the willow-bite, as it always lays its eggs in a hole in a tree, without over troubling itself to make a nest. When we put our hand in to feel for the eggs, if the bird was there it hissed like a snake, and many a boy have we seen whip his fingers out when he heard that alarming sound, quicker than over he put them in, believing that a snake was concealed in the hole. It is a famous destroyer of ants, which it takes up so rapidly on its glutinous tongue, that no human eye can follow the motion, for the ants seem impelled forward by some secret power, as one writer observes: 'as if drawn by a magnet.' This bird can both hop and walk, though it does not step out so soldier-like as the beautiful wagtail. Sometimes, while listening to the singing birds in spring, you will find all their voices hushed in a moment, and unless you are familiar with country objects, will be at a loss to divine the cause. Though you may not have heard it, some bird has raised a sudden cry of alarm, which causes them all to rush into the hedges and bushes for safety. That bird had seen the hovering hawk, and knew that, in another moment or so, he would drop down sudden as a thunderbolt on the first victim that he fixed his far-seeing eyes upon; and his rush is like the speed of thought. But he always remains nearly motionless in the air before he strikes, and this the birds seem to know, and their sight must be keen to see him so high. up as he generally is before he strikes. In the hedges they are safe, as there is no room there for the spread of his wings; and if he misses his quarry, he never makes a second dart at it. Sometimes the hawk catches a Tartar, as the one did that pounced upon and carried off a weasel, which, when high in the air, ate into the hawk's side, causing him to come down dead as a stone, when the weasel, who retained his hold of the hawk, ran off, not appearing to be the lea St. injured after his unexpected elevation. What a change have the March winds produced in the roads; they are now as hard as they were during the winter frost. But there was no cloud of dry dust then as there is now. When our forefathers repeated the old proverb which says, 'A peck of March dust is worth a king's ransom,' did they mean, we wonder, that its value lay in loosening and drying the earth, and making it fitter to till? In the old gardening books a dry day in March is always recommended for putting seed into the ground. To one who does not mind a noise there is great amusement to be found now in living near a rookery, for there is always something or another going on in that great airy city overhead, if it only be, as Washington Irving says, 'quarrelling for a corner of the blanket' while in their nests. They are nearly all thieves, and think nothing of stealing the foundation from one another's houses during the building season. When some incorrigible blackguard cannot be beaten into order, they all unite and drive him away; neck and crop do they bundle him out. Let him only shew so much as his beak in the rookery again after his ejectment, and the whole police force are out and at him in a moment. No peace will he ever have there any more during that season, though perhaps he may make it up again with. them during the next winter in the woods. We like to hear them cawing from the windy high elm-trees, which have been a rookery for centuries, and which overhang some old hall grey with the moss and lichen of forgotten years. The sound they make seems to give a quiet dreamy air to the whole landscape, and we look upon such a spot as an ancient English home, standing in a land of peace. HISTORICALWe derive the present name of this mouth from the Romans, among whom it was at an early period the first month of the year, as it continued to be in several countries to a comparatively late period, the legal year beginning even in England on the 25th of March, till the change of the style in 1752. For commencing the year with this month there seems a sufficient reason in the fact of its being the first season, after the dead of the year, in which decided symptoms of a renewal of growth take place. And for the Romans to dedicate their first month to Mars, and call it Martins, seems equally natural, considering the importance they attached to war, and the use they made of it. Among our Saxon forefathers, the month bore the name of Lenet-monat,-that is, length-month, -in reference to the lengthening of the day at this season, the origin also of the term Lent. 'The month,' says Brady, 'is portrayed as a man of a tawny colour and fierce aspect, with a helmet on his head-so far typical of Mars-while, appropriate to the season, he is represented leaning on a spade, holding almond blossoms and scions in his left hand, with a basket of seeds on his arm, and in his right hand the sign Aries, or the Ram, which the sun enters on the 20th of this month, thereby denoting the augmented power of the sun's rays, which in ancient hieroglyphics were expressed by the horns of animals. CHARACTERISTICS OF MARCHMarch is noted as a dry month. Its dust is looked for, and becomes a subject of congratulation, on account of the importance of dry weather at this time for sowing and planting. The idea has been embodied in proverbs, as 'A peck of March dust is worth a king's ransom,' and 'A dry March never begs its bread.' Blustering winds usually prevail more or less through-out a considerable part of the month, but mostly in the earlier portion. Hence, the month appears to change its character as it goes on; the re-mark is, 'It comes in like a lion, and goes out like a lamb.' The mean temperature of the month for London is stated at 43.9° ; for Perth, in Scotland, at 43° ; but, occasionally, winter reappears in all its fierceness. At London the sun rises on the first day at 6:34; on the last at 5:35, being an extension of upwards of an hour. |