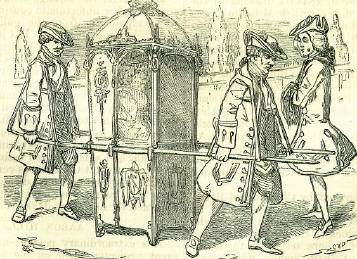

8th JulyBorn: John de la Fontaine, French writer of tales and fables, 1621, Chdteau-Thierry. Died: Peter the Hermit, preacher of the first Crusade, 1108: Pope Gregory XV, 1623: Dr. Robert South, eminent English preacher, 1716: Second Marshal Villeroi, 1730: Jean Pierre Niceron, useful writer, 1738, Paris; Jean Baseillac (Frere Come), eminent French lithotomist, 1781; Torbern Bergmann, Swedish chemist and naturalist, 1784, Medevi, near Upsala; Edmund Burke, statesman, orator, and miscellaneous writer, 1797, Beaonlfield, Backs; Sir Edward Parry, arctic voyager, 1855, Ems. Feast Day: St. Procopius, martyr, about 303; Saints Kilian, Colman, and Totnan, martyrs, 688; St. Withburge, virgin, of Norfolk, 743; St. Grimbald, abbot of New Minstre, 903; Blessed Theobald, abbot of Vaux de Cernay, 1247; St. Elizabeth, queen of Portugal, 1336. PETER THE HERMITThere is no more extraordinary episode in the annals of the world, than the History of the Crusades. To understand it, we must previously have some sense of the leading form which had been given to religion in the eleventh and twelfth centuries-an intense contemplation of the sufferings and merits of Christ, with a bound-less feeling of gratitude and affection towards his name. Already had this feeling caused multitudes to pilgrimise through barbarous countries to pay their devotions on the scene of his passion. It needed but an accident to make the universal European sentiment take the form of some wild and wonderful series of acts. In the north of France, there lived a man of low origin, named Peter, naturally active and restless, but who by various causes was drawn at last into a religions and anchoritic life, in which he became liable to visions and spiritual impulses, all thought by him to be divine. It was impressed upon him that the Deity had constituted him one of His special instruments on earth, and, as usual, others soon came to view him in that character, to thrill under his preachings, and to believe in his miraculous gifts. The rage for pilgrimages to the East drew the hermit Peter from his retreat, and, like the rest, he went to Jerusalem, where his indignation was moved by the manner in which the Christians were treated by the infidels. He heard the relation of their sufferings from the lips of the patriarch Simeon, and with him in private lamented over them, and talked of the possibility of rescuing the sufferers. It was in these conversations that the project was formed of exciting the warriors of the West to unite together for the recovery of the Holy Land from the power of the infidels. Peter's enthusiasm now led him to believe that he was himself the man destined for this great work, and on one occasion, when he was kneeling before the holy sepulchre, he believed that he had a vision, in which Jesus Christ appeared to him, announced to him his mission, and ordered him to lose no time in setting about it. Impressed with this idea, he left Palestine, and proceeded to Rome, where Urban II was then pope. Urban embraced the project with ardour, treated. Peter the Hermit as a prophet, and enjoined him to go abroad and announce the approaching deliverance of Jerusalem. Peter thereupon set out on his new pilgrimage. He rode on a mule, bare-headed and bare-foot, clothed in a long frock and a hermit's mantle of coarse woollen cloth, girded with a rope. In this manner he proceeded through Italy, crossed the Alps, and wandered through France and the greater part of Europe, everywhere received as a saint, and spreading among all classes an amazing amount of zeal for the Crusade, which he was now openly preaching. The enthusiasm which followed his steps was wonderful: people crowded to obtain the favour of touching his garments, and even the hairs of his mule were preserved as holy relics. His miracles were a subject of general conversation, and nobody doubted for a moment the truth of his mission. It was at this moment that the ambassadors of the Emperor Alexis Comnemus arrived in Rome, to represent to the pope the danger to which Constantinople was exposed from the invasions of the Turks, and to implore the assistance of the Western Christians. Pope Urban called a council, which met at Piacenza, in Lombardy, at the beginning of March 1095. So great had been the effect of Peter's preaching, that no less than 200 archbishops and bishops, 4000 other ecclesiastics, and 30,000 laymen attended this council, which was held in the open air, in a plain near the city: but various subjects divided its attention, and it came to no decision relative to the war against the infidels. The pope found that the Italians, who were, even at this early period, less bigoted. Catholics than the other peoples of Western Europe, were not very enthusiastic in the cause, and he resolved on calling another council, for the especial object of deliberating on the holy war, and in a country where he was likely to find more zeal. Accordingly, this council assembled in the November of the same year, at Clermont, in Auvergne: it was equally numerous with that of Piacenza, and, which was of most importance, Peter the Hermit attended in person, seated on his mule, and in the costume in which he had preached the Crusade through so many countries. After some preliminary business had been transacted, Peter was brought forward, and he described the sufferings of the Christians in the East in such moving language, and was so well seconded by the eloquence of the pope, that the whole assembly was seized with a fit of wild enthusiasm, and burst into shouts of, 'God wills it! God wills it!''It is true,'exclaimed the pope, 'God wills it, indeed, and you here see fulfilled the words of our Saviour, who promised to be present in the midst of the faithful when assembled in his name: it is he who puts into your mouths the words I have just heard: let them be your war-cry, and may they announce everywhere the presence of the God of armies! The pope then held forth a cross, and told them all to take that as their sign, and wear it upon their breasts, and the proposal was adopted amid a scene of the most violent agitation. Ademar de Monteil, bishop of Puy, advanced, and was the first to assume the cross, and multitudes hastened to follow his example. They called upon Urban to take the command of the expedition, but he excused himself personally, and appointed to the command, as his delegate, the zealous bishop of Puy, who is said to have been distinguished as a warrior before he became an ecclesiastic. Thus began the first Crusade. Armies-or rather crowds of men in arms-began now to assemble in various parts, in order to direct their march towards Constantinople. Among the first of these was the multitude who followed the preaching of Peter the Hermit, and who, impatient of delay, chose him for their leader, and were clamorous to commence their march. Peter, blinded by his zeal, accepted a position for which he was totally without capacity, and placed himself at their head, mounted on the same mule and in the same costume in which he had preached. His troop, starting from the banks of the Maas and the Moselle, and consisting origin-ally of people of Champagne and Burgundy, was soon increased by recruits from the adjacent districts, until he numbered under his command from 80,000 to 100,000 men. They came chiefly from the simpler and more ignorant classes of society, and they had been told so much of God's direct interference, that they were led to believe that he would feed and protect them on the road, and they did not even take the precaution to carry provisions or money with them. They expected to be supported by alms, and they begged on the way. Peter's army was divided into two bodies, of which the first, commanded by a man whose mean social position may be conjectured by his name of Walter the Penniless (Gaultier sans Avoir), marched in advance. They were received with enthusiasm by the Germans, who crowded to the same standard, and all went well until they came to the banks of the Morava and the Danube, and encountered the Hungarians and Bulgarians, both which peoples were nominally Christians: but the former took no interest in the Crusades, and the latter were not much better than savages. Walter's band of Crusaders passed through Hungary without any serious accident, and reached the country of the Bulgarians, where, finding themselves entirely destitute of provisions, they spread over the country, plundering, murdering, and destroying, until the population, flying to arms, fell upon them, and made a great slaughter. Those who escaped, fled with their leader towards Greece, and reached Nissa, the governor of which place administered to their pressing necessities: and, having learned by misfortune the advantage of observing something like discipline, they proceeded with more order till at length they reached Constantinople, where they were treated well, and allowed to encamp and await the other division, which was approaching under the command of Peter the Hermit. The zeal and incapacity of the latter led him into still greater disasters. In their passage through Hungary, the spots where some of the followers of Walter the Moneyless had been slaughtered, were pointed out to the Crusaders, and they were told that the Hungarians had entered into a plot for their destruction. Instead of enforcing the necessity of caution and discipline, Peter talked of vengeance, and sought only to inflame the passions of his followers. On their arrival at Semlin, they beheld the arms of some of the first band of Crusaders, who had been slain, suspended as a trophy over the gates, and Peter himself encouraged them to revenge their comrades. The inhabitants abandoned the town, fled, were overtaken, and 4000 of them slain, and their bodies thrown into the Danube, the waters of which. carried them down to Belgrade. The Crusaders returned to Semlin, which was given up to plunder, and they lived there in the most licentious manner, until news came that the Hungarians had assembled a great army to attack them, and then they abandoned the town, and hastened their march across Bulgaria. Everywhere the violence and licentiousness of the Crusaders had spread terror, and they now found the country abandoned, and suffered fearfully from the want of provisions. The people of Nissa had armed and fortified themselves, so that the Crusaders did not venture to attack them, but, having obtained a supply of provisions, had continued their march, when the ill-behaviour of their rear-guard provoked a collision, in which a considerable number of the Crusaders were slaughtered. Peter, informed of this affair, instead of hastening his march, returned to obtain satisfaction, and the irritating behaviour of his troops provoked a still greater conflict, in which 10,000 of the Crusaders were slaughtered, and the rest fled and took refuge in the woods and marshes of the surrounding country. That night, Peter the Hermit, who had taken refuge on a hill, had only 500 men about him, but next day his band numbered 7000, and a few days afterwards the number had been increased to 30,000. With these he continued his march, and, as their disasters had rendered them more prudent, they reached Constantinople without further misfortunes, and rejoined their companions. As the Emperor Alexis rather despised this undisciplined horde than otherwise, he received them with favour, and treated Peter the Hermit with the greatest distinction: but he lost no time in ridding himself of such troublesome visitors by transporting them to the other side of the Bosphorus. Those who had marched under the banner of Peter the Hermit, had now been joined by the remains of other similar hordes who had followed them, and who had experienced still greater disasters in passing through Hungary and Bulgaria: and, in addition to the other causes of disorder, they now experienced that of jealousy among themselves. They not only laid waste the country, and committed every sort of atrocity, but they quarrelled about the plunder: and, Peter himself having lost his authority, various individuals sought to be their leaders. The Italians and Germans, under the conduct of a chieftain named Renaud, separated from the rest of the army, left the camp which was established in the fertile country bordering on the Gulf of Nicomedia, and penetrated into the mountains in the neighbourhood of Nicaea, where they were destroyed by the Turks. The main army of the Crusaders, who now acknowledged the nominal authority of Walter, but who paid little attention to the orders of their chieftains, hastened imprudently to revenge the Italians and Germans, and had reached the plain of Nicaea, when they found themselves unexpectedly surrounded by the numerous and better disciplined army of the Turks, and, after a useless resistance, the whole army was put to the sword, or carried into captivity, and a vast mound of their bones was raised in the midst of the plain. Thus disastrously ended the expedition of Peter the Hermit. Of 300,000 men who had marched from Europe in the belief that they were going to conquer the Holy Land, all had perished, dither in the disasters of the route, or in the battle of Nicaea. Peter had left them before this great battle, disgusted with their vices and disorders, and had returned to Constantinople, to declaim against them as a horde of brigands, whose enormous sins had caused God to desert them. From this time the Hermit became a second-rate actor in the events of the Crusade. When the more noble army of the Crusaders, under the princes and great warriors of the West, arrived at Constantinople, he joined them, and accompanied them in their march, performing merely the part of an eloquent and zealous preacher; but at the siege of Antioch, he attempted to escape the sufferings of the Christian camp by flight, and was pursued and overtaken by Tancred, brought back, and compelled to take an oath to remain faithful to the army. This disgrace appears to have been wiped out by his subsequent conduct; and he was among the first ranks of the Crusaders who came in sight of Jerusalem. The wearied warriors were cheered by the enthusiastic eloquence with which he addressed them on the summit of the Mount of Olives; and in the midst of the slaughter, when the holy city was taken, the Christian soldiers crowded round him, as people had crowded round him when he first proclaimed the Crusade, and congratulated him on the fulfilment of his prophecies. Peter remained in the Holy Land until 1102, when he returned to Europe, with the Count of Montaign, a baron of the territory of Liege. On their way they were overtaken by a dreadful tempest, in which the Hermit made a vow to found a monastery if they escaped shipwreck. It was in fulfilment of this vow, that he founded the abbey of Neufmoutier, at Huy, on the Maas, in honour of the holy sepulchre. Here he passed the latter years of his life, and died in 1115. In the last century, his tomb was still preserved there, with a monumental inscription. BURKE'S ESTATE-HIS DAGGER-SCENE IN THE HOUSE OF COMMONSIt is very clear from the authentic biographies of Edmund Burke, that he entered upon literary and political life in London with little or no endowment beyond that which nature and a good education had given him. He wrote for his bread for several years, as many able but penniless Irishmen have since done and continue to do. At length, when several years past thirty, merging into a political career as private secretary, first to Single-speech Hamilton, and afterwards to the Marquis of Rockingham, he enters parliament for a small English burgh, and soon after-all at once-in 1767-he purchases an estate worth £23,000! In a large elegant house, furnished with all the adjuncts of a luxurious establishment, surrounded by 600 acres of his own land, driving a carriage and four, Burke henceforth appeared as a man of liberal and independent fortune. When surly but pure-hearted Samuel Johnson was shewn by him over all the splendours of Beaconsfield, he said: 'Non equidem invideo-miror magis '-I do not envy, I am only astonished; and then added, still more significantly: 'I wish you all the success which can be wished-by an honest man.' There was an unpleasant mystery here, which it was reserved for modern times to penetrate. One theory on the subject, set forth so lately as 1853, by an ingenious though anonymous writer, was that Burke was mainly indebted for the ability to purchase his estate to successful speculations in Indian stock. In Macknight's able work, The Life and Times of Edward Burke, published in 1858, an account of the transaction is given in tolerably explicit terms, but without leaving the character of Burke in the position which his admirers might wish. 'In 1767,' says this writer, 'when Lord. Rockingham refused to return again to office, and Burke, though in very straitened circumstances, adhered faithfully to his noble leader, it then occurred to the marquis that it was incumbent on him to do something for the fortune of his devoted friend. He advanced £10,000 to Burke, on a bond that it was understood would never be reclaimed. With those £10,000, £5000 raised on mortgage from a Dr. Saunders in Spring Gardens, and other £8000, doubtless obtained from the successful speculations of William and Richard Burke [his brothers] in Indian stock, Burke purchased the estate of Gregories. After the reverses of his relatives in the year 1769, all the money they had advanced to him was required. Lord Rockingham again came forward. From that time through many years of opposition, as Burke's fortune, so far from increasing, actually diminished under his unvarying generosity and the requirements of his position, this noble friend was his constant and unfailing resource. The loss of the agency for New York [by which Burke had £1000 a year for a short time] the marquis endeavoured to compensate by frequent loans. At the time of Lord Rockingham's death [1782], he may, on different occasions extending over fourteen years, have perhaps advanced on bonds, which though never formally required, Burke insisted on giving, the sum of about thirty thousand pounds. It appears, in short, that this brilliant statesman and orator maintained his high historical place for thirty years, wholly through pecuniary means drawn by him from a generous friend. The splendid mansion, the vineries and statuary, the four-horsed carriage, even the kind-hearted patronage to such men of genius as Barry and Crabbe, were all supported in a way that implies the entire sacrifice of Burke's independence. It is very sad to think of in one whom there was so much to admire; but it only adds another and hereto-fore undetected example to those we have, illustrating a fact in our political system, that it is no sphere for clever adventurers, independence in personal circumstances being the indispensable prerequisite of political independence.  Burke's dagger-scene in the House of Commons is an obscure point in his life-no one at the time gave any good account of it. On this matter also we have latterly obtained some new light. The great Whig, as is well known, was carried by the French Revolution out of all power of sober judgment, and made a traitor, it might be said, to all his old affections. When at the height of the rabies, having to speak on the second reading of the Alien Bill, December 28, 1792, he called, in passing, at the office of Sir Charles M. Lamb, under-secretary of state. It was only three months from the massacres of Paris. England was in high excitement about the supposed existence of a party amongst ourselves, who were disposed to fraternise with the ensanguined reformers of France, and imitate their acts. Some agent for that party had sent a dagger to a Birmingham manufacturer, with an order for a large quantity after the same pattern. It was a coarsely-made weapon, a foot long in the blade, and fitted to serve equally as a stiletto and as a pike-head. The Birmingham manufacturer, disliking the commission, had come up to the under-secretary's office, to exhibit the pattern dagger, and ask advice. He had left the weapon, which Burke was thus enabled to see. The illustrious orator, with the under-secretary's permission, took it along with him to the House, and, in the course of a flaming tirade about French atrocities, and probable imitations of them in England, he drew the dagger from his bosom, and threw it down on the floor, as an illustration of what every man might shortly expect to see levelled at his own throat. There were of course sentiments of alarm raised by this scene; but probably the more general feeling was one of derision. In this way the matter was taken up by Gillray, whose caricature on the subject we here reproduce in miniature, as a curious memorial of a crisis in our history, and also as giving a characteristic portrait of one of our greatest men. WILLIAM HUNTINGTON'S EPITAPHWhen a man's epitaph is written by himself in anticipation of his death, there may generally be found in it some indication of his character, such as probably would not otherwise have transpired. Such was certainly the case in reference to William or the Rev. William Huntington, who loved to couple the designations 'coal-heaver' and 'sinner saved' with his name. On the 8th of July 1813, the remains of this eccentric man were transferred from a temporary grave at Tonbridge Wells to a permanent one at Lewes. The stone at the head of the grave was inscribed with an epitaph which he himself had written a few days before his death-leaving a space, of course, for the exact date. 'Here lies the Coal-heaver, who departed this life (July 1, 1813), in the (69th) year of his age; beloved of his God, but abhorred by men. The Omniscient Judge, at the Great Assize, shall ratify and confirm this, to the confusion of many thousands; for England and its metropolis shall know that there bath been a prophet among them. W. H. S. S.-This S. S. meant 'sinner saved.' The career of the man affords a clue to the state of mind which could lead to the production of such an epitaph. William Hunt was born in the Weald of Kent, of very poor parents. He complained, in later life, that 'unsanctified critics' laughed at him for his ignorance; and certain it is that he never could get over the defects of his education. He struggled for a living as an errand-boy, then as a labourer, then as a cobbler. While engaged in the last-named trade, he took up the business of a preacher. He would place his work on his lap, and a Bible on a chair beside him; and, while working for his family, he collected materials for his next sermon. At what time, or for what reason, he changed his name from Hunt to Huntington, is not clear; but we find him coming up from Thames-Ditton to London, 'bringing two large carts with furniture and other necessaries, besides a post-chaise well filled with children and cats.' He became a preacher at Margaret Street Chapel, and attached a considerable number of persons to him by his peculiar denunciatory style. In 1788, his admirers built him a chapel in Gray's Inn Road, which he named 'Providence Chapel.' When a person attributes to Providence the good that comes to him, his sentiment is at all events worthy of respect; but the peculiarity in Huntington's case was the whimsical way in which everyday matters were thus treated. When £9000 had been spent on the chapel, various gifts of chairs, a tea-caddy full of tea, a looking-glass, a bed and bedstead for the vestry, 'that I might not be under the necessity of walking home in the cold winter nights'-are spoken of by him as things that Providence had sent him. He had a keen appreciation of worldly goods, however; for he refused to officiate in the chapel until the freehold had been made over absolutely to himself. Wishing afterwards to enlarge his chapel a little, he applied for a bit of ground near it from the Duke of Portland, but demurred at the ground-rent asked. Therefore, says he, 'finding nothing could be done with the earth-holders, I turned my eyes another way, and determined to build my stories in the heavens, where I should find more room and less cost '-in plain English, he raised the building another story. His manner towards his hearers was dogmatic and arrogant. Having once taken the designation of 'Sinner Saved,' he observed no bounds in addressing others. His pulpit-oratory, always vigorous, was not unfrequently interlarded with such expressions as-'Take care of your pockets!'-'Wake that snoring sinner!'-'Silence that noisy numb-skull!'-'Turn out that drunken dog!' With a certain class of minds, however, Huntington had great influence. Some time after the death of his first wife, he married the widow of Sir James Sanderson, at one time lord mayor of London: by which alliance he became possessed of much property. On one occasion, a sale of some of his effects took place at his residence at Pentonville, when sixty guineas were given for an old arm-chair by one of his many admirers. Two or three books which he published were quite in character with the epitaph he afterwards wrote-an intense personal vanity pervading all else that might be good in him. A KING AND HIS DUMB FAVOURITESKing James I, although a remorseless destroyer of animals in the chase, had, like many modern sportsmen, an intense fondness for seeing them around him, happy and well cared for, in a state of domesticity. In 1623, John Bannal obtained a grant of the king's interest in the leases of two gardens and a tenement in the Minories, on the condition of building and maintaining a house, wherein to keep and rear his majesty's newly imported silkworms - Sir Thomas Dale, one of the settlers of the then newly formed colony of Virginia, returning to Europe on leave, brought with him many living specimens of American zoology; amongst them, some flying squirrels. This coming to his majesty's ears, he was seized with a boyish impatience to add them to the private menagerie in St. James's Park. At the council-table, and in the circle of his courtiers, he recurs again and again to the subject, wondering that Sir Thomas had not given him the 'first pick' of his cargo of curiosities. He reminded them how the recently arrived Muscovite ambassador had brought him live sables, and, what he loved even better, splendid white gyrfalcons of Iceland; and when Buckingham suggested that, in the whole of her reign, Queen Elizabeth had never received live sables from the czar, James made special inquiries if such were really the case. Henry Wriothesley, fourth Earl of Southampton, one of the council, and governor and treasurer of the Virginia Company, better known to us as the friend and patron of Shakspeare, wrote as follows to the state secretary, the Earl of Salisbury: 'Talking with the king by chance, I told him of the Virginian squirrels, which they say will fly, whereof there are now divers brought into England, and he presently and very earnestly asked me if none of them was provided for him, and whether your lordship had none for him-saying he was sure Salisbury would get him one of them. I would not have troubled you with this, but that you know full well how he is affected to these toys; and with a little inquiry of any of your folks, you may furnish yourself to present him at his coming to London, which will not be before Wednesday next-the Monday before to Theobald's, and the Saturday before to Royston.' Some one of his loving subjects, desirous of ministering to his favourite hobby, had presented him with a cream-coloured fawn. A nurse was immediately hired for it, and the Earl of Shrewsbury commissioned to write as follows to Miles Whytakers, signifying the royal pleasure as to future procedure: 'The king's majesty hath commissioned me to send this rare beast, a white hind calf, unto you, together with a woman, his nurse, that hath kept it, and bred it up. His majesty would have you see it be kept in every respect as this good woman cloth desire, and that the woman may be lodged and boarded by you, until his majesty come to Theobald's on Monday next, and then you shall know further of his pleasure. What account his majesty maketh of this fine beast you may guess, and no man can suppose it to be more rare than it is, therefore I know that your care of it will be accordingly. So in haste I bid you very heartily farewell. At Whitehall, this 6th Nov. 1611. 'P. S. The wagon and the men are to be sent home; only the woman is to stay with you, until his majesty's coming hither, ,and as long after as it shall please his majesty.' About the year 1629, the king of Spain effected an important diversion in his own favour, by sending the king-priceless gift!-an elephant and five camels. 'Going through London, after midnight,' says a state-paper letter, 'they could not pass unseen' and the clamour and outcry raised by some street-loiterers at sight of their ponderous hulk and ungainly step, roused the sleepers from their beds in every district through which they passed. News of this unlooked-for addition to the Royal Zoological Garden in St. James' Park, is conveyed to Theobald's as speedily as horse-flesh, whip, and spur could do the work. Then arose an interchange of missives to and fro, betwixt the king, my lord treasurer, and Mr. Secretary Conway, grave, earnest, and deliberate, as though involving the settlement or refusal of some treaty of peace. In muttered sentences, not loud but deep, the thrifty lord treasurer shews 'how little he is in love with royal presents, which cost his master as much to maintain as would a garrison.' No matter. Warrants are issued to the officers of the Mews, and to Buckingham, master of the horse, 'that the elephant is to be daily well dressed and fed, but that he should not be led forth to water, nor any admitted to see him, without directions from his keeper, which they were to observe and follow in all things concerning that beast, as they will answer for the contrary at their uttermost peril. The camels are to be daily grazed in the park, but brought back at night, with all possible precautions to screen them from the vulgar gaze. 'In the blessed graciousness of his majesty's disposition,' £150 was to be presented to Francisco Romano, who brought them over-though the meagre treasury was hardly able to yield up that slim, and her majesty's visit to 'the Bath' must be put off to a more convenient season, for want of money to bear her charges. Then Sir Richard Weston was commissioned by Mr. Secretary Conway to estimate the annual cost of maintaining the royal quadruped, his master having decided to take the business into his own hands. He suggested economy, but does not seem to have succeeded, for the state papers for August 1623 furnish the following 'breefe noate what the chardges of the elephant and his keepers are in the yeare: Such is the gross amount, according to the manuscript, but not according to Cocker. Should the above be a specimen of Mr. Secretary Conway's arithmetic, we can only hope his foreign policy was somewhat better than his figures. This calculation, however, by no means embraced every item of the costly hill of fare-'Besides,' adds the manuscript, 'his keepers afirme that from the month of September until April, he must drink (not water) but wyne-and from April unto September, he must have a gallon of wyne the daye.' A pleasant time of it must this same elephant have had, with his modest winter-allowance of six bottles per them, in exchange for the Spaniard's lenten quarters. |