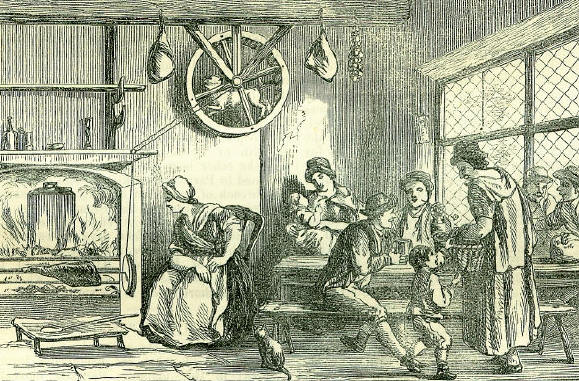

8th AprilBorn: John C. Loudon, writer on botany, &c., 1783, Cambuslang, Lanarkshire. Died: Caracalla, Roman emperor, assassinated, 217, Edessa; Pope Benedict III, 858; John the Good, King of France, 1364, Savoy Palace, London; Lorenzo de Medicis, 'the Magnificent,' 1492, Florence; Dr. Thomas Gale, learned divine and editor, 1702, York. Feast Day: St. Dionysius, of Corinth, 2nd century. St. AEdesius, martyr, 306. St. Perpetuus, bishop of Tours, 491. St. Walter, abbot of St. Martin's, near Pontoise, 1099. B. Albert, patriarch of Jerusalem, 1214. THE CAPTIVITY OF JOHN, KING OF FRANCE, AT SOMERTON CASTLEJohn I (surnamed 'Le Bon') mounted the throne of France in 1350, at the age of thirty. He began his reign most inauspiciously by beheading the Count d'Eu, an act which alienated the affections of all his greater nobles from him, and which he in vain endeavoured to repair by instituting the order of the 'Star,' in imitation of that of the 'Garter,' founded by the sovereign of England. Next he was much perplexed by the continued enmity of Charles d'Evereux, King of Navarre. Finally, the Black Prince, invading his realm, ravaged Limousin, Auvergne, Berri, and Poitou. Incensed by the temerity of his English assailants, John hastily raised an army of 60,000 men, swearing that he would give battle to the prince immediately. The two armies met at Maupertnis, near Poitiers, September 19th, 1356, when the Black Prince, with only 8,000 men under his command, succeeded in routing the French army most completely, and taking the king and his fourth son, Philip, a brave youth of fifteen, prisoners. The royal captives were first taken to Bordeaux, and thence brought to England, where they landed, May 4th, 1357. During the first year of his captivity, John resided at the palace of the Savoy in London, where he was well entertained, enjoying full liberty, and often receiving visits from King Edward and Queen Philippa. Towards the close of the year 1358, a series of restrictions began to be imposed upon the captives, accompanied by reductions of their suite; but this change was the result of political caution, not of any unnecessary severity, and ended in their transfer to Somerton Castle, near Navenby, in Lincolnshire, August 4th, 1359. William Baron d'Eyncourt, a noble in whom the king could place the utmost confidence, was appointed custodian of the royal prisoners. Previous to this coming into Lincolnshire, in accordance with an edict of Edward III, John had been forced to dismiss forty-two of his attendants; he still, however, retained about the same number around his person. Among these were two chaplains, a secretary, a clerk of the chapel, a physician, a maitre d'hôtel, three pages, four valets, three wardrobe men, three furriers, six grooms, two cooks, a fruiterer, a spiceman, a barber, and a washer, besides some higher officers, and a person bearing the exalted name of le roy de menestereulx,' who appears to have been a maker of musical instruments and clocks as well as a minstrel; and last, but not least, 'Maitre Jean le fol.' The Somerton Castle furniture being utterly insufficient for such a vast increase of inmates, the captive king added a number of tables, chairs, forms, and trestles, besides fittings for the stables, and stores of fire-wood and turf. He also fitted up his own chamber, that of the Prince Philip, and of M. Jean le fol, besides the chapel, with hangings, curtains, cushions, ornamented coffers, sconces, &c., the furniture of each of these filling a separate wagon when the king left Somerton. Large consignments of good Bordeaux wines were transmitted from France to the port of Boston for the captive king's use, as much as a hundred and forty tuns being sent at one time as a present, intended partly for his own use and partly as a means of raising money to keep up his royal state. One of the costly items in the king's expenditure was sugar, together with spices bought in London, Lincoln, and Boston, immense quantities of which we may infer were used in the form of confectionery; for in the household books we meet constantly with such items as eggs to clarify sugar, roses to flavour it with, and cochineal to colour it. These bon-bons appear to have cost about three shillings the pound; at least such is the price of what is termed 'sucre roset vermeil,' and especial mention is made of a large silver gilt box made for the king as a 'bonboniere,' or receptacle for such sweets. In the article of dress John was most prodigal. In less than five months he ordered eight complete suits, besides one received as a present from the Countess of Boulogne, and many separate articles. One ordered for Easter was of Brussels manufacture, a marbled violet velvet, trimmed with miniver; another for Whitsuntide, of rosy scarlet, lined with blue taffeta. The fur and trimmings of these robes formed a most costly additional item, there having been paid to William, a furrier of Lincoln, £17, 3s. 9d. for 800 miniver skins, and 850 ditto of 'gris;' also £8, 10s. to Thornsten, a furrier of London, for 600 additional miniver skins, and 300 of gris,' all for one set of robes. Thus 2,550 skins, at a cost of £25,13s. 9d., were used in this suit, and the charge for making it up was £6, 8s. Indeed, so large were the requirements of the captive king and his household in this particular, that a regular tailoring establishment was set up in Lincoln by his order, over which one M. Tassin presided. The pastimes he indulged in were novel-reading, music, chess, and backgammon. He paid for writing materials in Lincolnshire three shillings to three shillings and sixpence for one dozen parchments, sixpence to ninepence for a quire of paper, one shilling for an envelope with its silk binder, and fourpence for a bottle of ink. The youthful tastes of the valorous Prince Philip appear to have been of what we should consider a more debased order than his royal father's. He had dogs, probably greyhounds, for coursing on the heath adjoining Somerton, and falcons, and, I am sorry to add, game cocks, too; a charge appearing in the royal household accounts for the purchase of one of these birds, termed, in language characteristic of the period, 'un coo a, faire jouster.' One very marked trait in King John's character was his love of almsgiving. His charitable gifts, great and small, public and private, flowed in a ceaseless stream when a captive in adversity, no less than when on the throne in prosperity. Wherever he was he made a small daily offering to the curate of the parish, besides presenting larger sums on the festivals of the church. For instance, he gave to the humble Cure of Boby (Boothby) a sum equal to twelve shillings, for masses offered by him at Christmas; eight shillings at the Epiphany; and four shillings and fourpence at Candlemas. The religious orders also received large sums at his hands; on each of the four mendicant societies of Lincoln he bestowed fifteen escuz, or ten pounds. On his way from London to Somerton, he offered at Grantham five nobles (£1, 13s. 4d.); gave five more nobles to the preaching friars of Stamford, and the same sum to the shrine of St. Albans. In fact, wherever he went, churches, convents, shrines, recluses, and the poor and unfortunate, were constant recipients of his bounty. On the 21st of March 1360, King John was removed from Somerton, and lodged in the Tower of London, the journey occupying seven days. Two months after (May 19), he was released on signing an agreement to pay to England 3,000,000 of gold crowns (or £1,500,000) for his ransom, of which 600,000 were to be paid within four months of his arrival in France, and 400,000 a year, till the whole was liquidated, and also that his son, the Due d'Anjou, and other noble personages of France, should be sent over as hostages for the same. The last act of this unfortunate monarch shews his deep seated love of truth and honour. On the 6th of December 1363, the Duc d'Anjou and the other hostages broke their parole, and returned to Paris. Mortified beyond measure at this breach of trust, and turning a deaf ear to the remonstrances of his council, John felt himself bound in honour to return to the English coast, and accordingly four days afterwards he crossed the sea once more, and placed himself at the disposal of Edward. The palace of the Savoy was appointed as his residence, where he died after a short illness in the spring of 1364. THE TURNSPITA few months ago the writer happened to be at an auction of what are technically termed fixtures; in this instance, the last moveable furnishings of an ancient country-house, about to be pulled down to make room for a railway station. Amongst the many lots arranged for sale, was a large wooden wheel enclosed in a kind of circular box, which gave rise to many speculations respecting the use it had been put to. At last, an old man, the blacksmith of the neighbouring village, made his appearance, and solved the puzzle, by stating that it was a dog-wheel,'-a machine used to turn a spit by the labour of a dog; a very common practice down to a not distant period, though now scarcely within the memory of living men. Besides the blacksmith, the writer has met with only one other person who can remember seeing a turnspit dog employed in its peculiar vocation; but no better authority can be cited than that of Mr. Jesse, the well-known writer on rural subjects, who thus relates his experiences:  How well do I recollect in the days of my youth watching the operations of a turnspit at the house of a worthy old Welsh clergyman in Worcestershire, who taught me to read! He was a good man, wore a bushy wig, black worsted stockings, and large plated buckles in his shoes. As he had several boarders as well as day scholars, his two turnspits had plenty to do. They were long-bodied, crook-legged, and ugly dogs, with a suspicious, unhappy look about them, as if they were weary of the task they had to do, and expected every moment to be seized upon to perform it. Cooks in those days, as they are said to be at present, were very cross; and if the poor animal, wearied with having a larger joint than usual to turn, stopped for a moment, the voice of the cook might be heard rating him in no very gentle terms. When we consider that a large solid piece of beef would take at least three hours before it was properly roasted, we may form some idea of the task a dog had to perform in turning a wheel during that time. A pointer has pleasure in finding game, the terrier worries rats with eagerness and delight, and the bull-dog even attacks bulls with the greatest energy, while the poor turnspit performs his task with compulsion, like a culprit on a tread-wheel. subject to scolding or beating if he stops a moment to rest his weary limbs, and is then kicked about the kitchen when the task is over.' The services of the turnspit date from an early period. Doctor Caius, founder of the college at Cambridge which bears his name, and the first English writer on dogs, says: There is comprehended under the curs of the coarsest kind a certain dog in kitchen service excellent. For when any meat is to be roasted, they go into a wheel, which they turning about with the weight of their bodies, so diligently look to their business, that no drudge nor scullion can do the feat more cunningly, whom the popular sort hereupon term turnspits. The annexed illustration, taken from Remarks on a Tour to North and South Wales, published in 1800, clearly exhibits how the dog was enabled to perform his curious and uncongenial task. The letterpress in reference to it says: Newcastle, near Carmarthen, is a pleasant village; at a decent inn here a dog is employed as turnspit; great care is taken that this animal does not observe the cook approach the larder; if he does, he immediately hides himself for the remainder of the day, and the guest must be contented with more humble fare than intended. One dog being insufficient to do all the roasting for a large establishment, two or more were kept, working alternately; and each animal well knowing and noting its regular turn of duty, great difficulty was experienced in compelling it to work out of the recognised system of rotation. Buffon relates that two turnspits were employed in the kitchen of the Duc de Lianfort at Paris, taking their turns every other day to go into the wheel. One of them, in a fit of laziness, hid itself on a day that it should have worked, so the other was forced to go into the wheel instead. When the meat was roasted, the one that had been compelled to work out of its turn began to bark and wag its tail till it induced the scullions to follow it; then leading them to a garret, and dislodging the skulker from beneath a bed, it attacked and killed its too lazy fellow-worker. A somewhat similar circumstance occurred at the Jesuits' College of La Flèche. One day, the cook, having prepared the meat for roasting, looked for the dog whose turn it was to work the wheel for that day; but not being able to find it, he attempted to employ the one whose turn it was to be off duty. The dog resisted, bit the cook, and ran away. The man, with whom the dog was a particular favourite, was much astonished at its ferocity; and the wound being severe and bleeding profusely, he went to the surgeon of the College to have it dressed. In the meantime the dog ran into the garden, found the one whose turn it was to work the spit for that day, and drove it into the kitchen; where the deserter, seeing no opportunity of shirking its day's labour, went into the wheel of its own accord, and began to work. Turnspits frequently figure in the old collections of anecdotes. For instance, it is said that the captain of a ship of war, stationed in the port of Bristol for its protection in the last century, found that, on account of some political bias, the inhabitants did not receive him with their accustomed hospitality. So, to punish them, he sent his men ashore one night, with orders to steal all the turnspit dogs they could lay their hands upon. The dogs being conveyed on board the ship, and snugly stowed away in the hold, consternation reigned in the kitchens and dining-rooms of the Bristol merchants; and roast meat rose to a premium during the few days the dogs were confined in their floating prison. The release of the turnspits was duly celebrated by many dinners to the captain and his officers. In an exceeding rare collection of poems, entitled Norfolk Drollery, there are the following lines Upon a clog called Fuddle, turnspit at the Popinjay, in Norwich Fuddle, why so? Some fuddle-cap sure came Into the room, and gave him his own name; How should he catch a fox? he'll turn his back Upon tobacco, beer, French wine, or sack. A hone his jewel is; and he does scorn, With AEsop's cock, to wish a barley-corn. There's not a soberer dog, I know, in Norwich, What would ye have him drunk with porridge? This I confess, he goes around, around, A hundred times, and never touches ground; And in the middle circle of the air He draws a circle like a conjuror. With eagerness he still does forward tend, Like Sisyphus, whose journey has no end. He is the soul (if wood has such a thing?) And living posy of a wooden ring. He is advanced above his fellows, yet He does not for it the least envy get. He does above the Isle of Dogs commence, And wheels the inferior spit by influence. This, though, befalls his more laborious lot, He is the Dog-star, and his days are hot. Yet with this comfort there's no fear of burning, 'Cause all the while the industrious wretch is turning. Then no more Fuddle say; give him no spurns, But wreak your spleen on one that never turns, And call him, if a proper name he lack, A four-foot hustler, or a living Jack. The poets not unfrequently used the poor turnspit as an illustration or simile. Thus Pitt, in his Art of Preaching, alluding to an orator who speaks much, but little to the purpose, says: His arguments in silly circles run, Still round and round, and end where they begun. So the poor turnspit, as the wheel runs round, The more he gains, the more he loses ground. A curious political satire, published in 1705, and entitled The Dog in the Wheel, shews, under the figure of a turnspit dog, how a noisy demagogue can become a very quiet placeman. The poem commences thus: Once in a certain family, Where idleness was disesteemed; For ancient hospitality, Great plenty and frugality, 'Bove others famous deemed. No useless thing was kept for show, Unless a paroquet or so; Some poor relation in an age, The chaplain, or my lady's page: All creatures else about the house Were put to some convenient use. Nay, ev'n the cook had learned the knack With cur to save the charge of jack; So trained 'em to her purpose fit, And made them earn each bit they ate. Her ready servants knew the wheel, Or stood in awe of whip and bell; Each had its task, and did it well. The poem as it proceeds describes the dogs in office lying by the kitchen fire, and discussing some savoury bones, the well-earned rewards of the day's exertions. The demagogic cur, entering, calls them mean, paltry wretches, to submit to such shameful servitude; unpatriotic vermin to chew the bitter bones of tyranny. For his part, he would rather starve a thousand times over than do so. Woe be to the tyrannic hand that would attempt to make him a slave, while he had teeth to defend his lawful liberty-and so forth. At this instant, however, the cook happens to enter: And seeing him (the demagogue) among the rest, She called him very gently to her, And stroked the smooth, submissive cur: Who soon was hushed, forgot to rail, He licked his lips, and wagged his tail, Was overjoyed he should prevail Such favour to obtain. Among the rest he went to play, Was put into the wheel next day, He turned and ate as well as they, And never speeched again. |