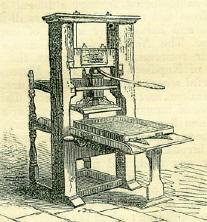

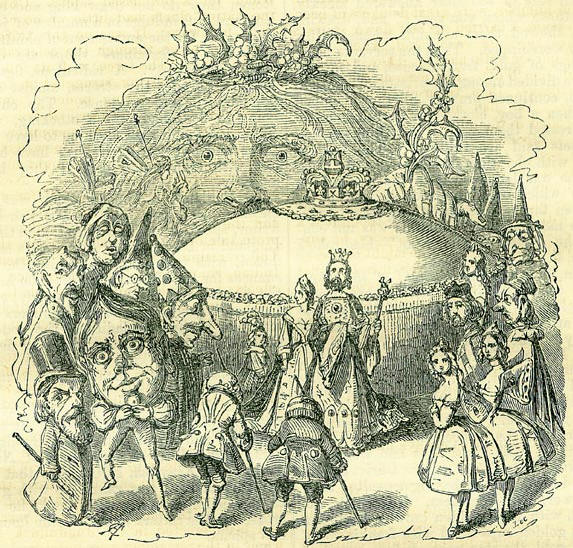

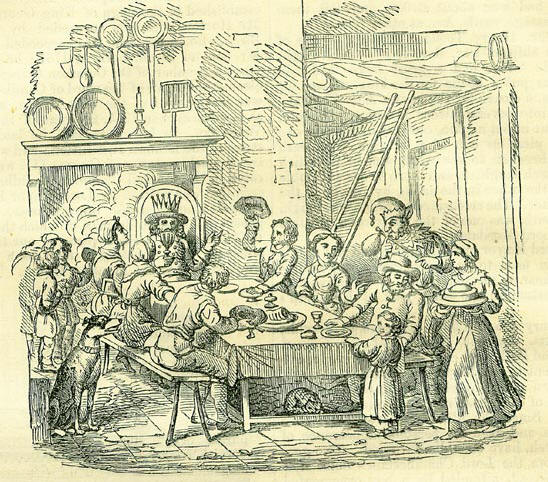

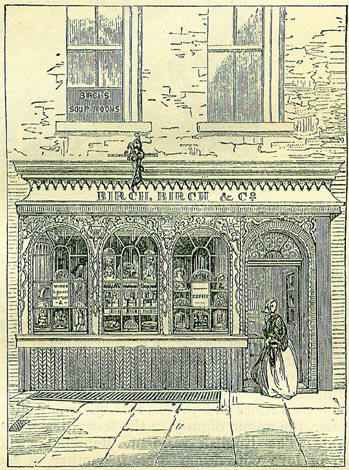

6th JanuaryBorn: Richard II, King of England, 1366; Joan d'Arc, 1402; Peter Metastasio, poet, 1698; Benjamin Franklin, philosopher, Boston, U.S., 1706; David Dale, philanthropist, 1739; George Thomas Doo, engraver, 1800. Died: Seth Ward, Bishop of Salisbury, mathematician, 1689; John Dennis, critic, 1734; Madame d'Arblay (Frances Burney), novelist, 1840; James Smith, comic poet, 1840; Fanny Wright, lady politician, 1853. Feast Day: St. Melanius, bishop, 490. St. Nilammon, Hermit. St. Peter, abbot of St. Austin's, Canterbury, 608. BENJAMIN FRANKLIN Modern society has felt as if there were some-thing wanting in the character of Franklin; yet what the man positively had of good about him was, beyond all doubt, extremely good. Self-denial, energy, love of knowledge, sagacity to I discern and earnestness to pursue what was calculated to promote happiness amongst mankind, scientific ingenuity, courage in the protection of patriotic interests against misrule-all were his. How, few men possess half so many high qualities It is an extremely characteristic circumstance that, landing at Falmouth from a dangerous voyage, and going to church with his son to return thanks to God for their deliverance, he felt it as an occasion when a Catholic would have vowed to build a chapel to some saint: 'not being a Catholic,' said the philosopher, 'if I were to vow at all, it would be to build a lighthouse' [the article found chiefly wanting towards the end of their voyage]. It is little known that it was mainly by the advice of Franklin that the English government resolved to conquer Canada, and for that purpose sent out Wolfe's expedition. While in our island at that time (1759), as agent for the colony of Pennsylvania, he made an excursion to Scotland, accompanied by his son. His reputation as a man of science had made him well known there, and he was accordingly received with distinction by Hume, Robertson, Lord Kames, and other literary men of note, was made a doctor of St. Andrew's University, and a burgess by the Town Council of Edinburgh. Franklin paid a long visit to Lord Kames at his seat of Kames in Berwickshire, and when he came away, his host and hostess gave him a convoy into the English border. Some months after, writing to his lordship from London, he said: 'How much more agreeable would our journey have been, if we could have enjoyed you as far as York! We could have beguiled the way by discoursing on a thousand things that now we may never have an opportunity of considering together; for conversation warms the mind, enlivens the imagination, and is continually starting fresh game that is immediately pursued and taken, and which would never have occurred in the duller intercourse of epistolary correspondence. So that when ever I reflect on the great pleasure and ad vantage I received from the free communication of sentiment in the conversation we had at Kames, and in the agreeable little rides to the Tweedside, I shall ever regret our premature parting.' 'Our conversation,' he added, 'until we came to York, was chiefly a recollection of what we had seen and heard, the pleasure we had enjoyed, and the kindnesses we had received in Scotland, and how far that country had exceeded our expectations. On the whole, I must say, I think the time we spent there was six weeks of the densest happiness I have ever met with in any part of my life; and the agreeable and instructive society we found there in such plenty, has left so pleasing an impression on my memory, that, did not strong connections draw me elsewhere, I believe Scotland would be the country I should choose to spend the remainder of my days in.' Soon after, May 3rd, 1760, Franklin communicated to Lord Kames a plan he had formed to write a little book under the title of The Art of Virtue. 'Many people,' he said, 'lead bad lives that would gladly lead good ones, but do not know how to make the change. They have frequently resolved and endeavoured it; but in vain, because their endeavours have not been properly conducted. To expect people to be good, to be just, to be temperate, &c., without shewing them how they should become so, seems like the ineffectual charity mentioned by the Apostle, which consisted in saying to the hungry, the cold, and the naked, 'Be ye fed, be ye warmed, be ye clothed,' without shewing them how they should get food, fire, or clothing. 'Most people have naturally some virtues, but none have naturally all the virtues.' 'To inquire those that are wanting, and secure what we require as well as those we have naturally, is the subject of an art. It is properly an art, as painting, navigation, or architecture. If a man would become a painter, navigator, or architect, it is not enough that he is advised to be one, that he is convinced by the arguments of his adviser that it would be for his advantage to be one, and that he resolves to be one; but he must also be taught the principles of the art, be shewn all the methods of working, and how to acquire the habits of using properly all the instruments; and thus regularly and gradually he arrives, by practice, at some perfection in the art. If he does not proceed thus, he is apt to meet with difficulties that might discourage him, and make him drop the pursuit.' 'The Art of Virtue has also its instruments, and teaches the manner of using them. 'Christians are directed to have faith in Christ, as the effectual means of obtaining the change they desire. It may, when sufficiently strong, be effectual with many; for a full opinion, that a teacher is infinitely wise, good, and powerful, and that he will certainly reward and punish. the obedient and disobedient, must give great weight to his precepts, and make them much more at-tended to by his disciples. But many have this faith in so weak a degree, that it does not produce the effect. Our Art of Virtue may, therefore, be of great service to those whose faith is unhappily not so strong, and may come in aid of its weakness. Such as are naturally well-disposed, and have been so carefully educated as that good habits have been early established and bad ones prevented, have less need of this art; but all may be more or less benefited by it.' Between two men of such sentiments as Franklin and Lord Kames, thrown together for six weeks, the subject of religious toleration we may well suppose to have been frequently under discussion. Franklin communicated to his Scotch friend a small piece, of the nature of an apologue, designed to give a lesson of toleration, and which Kames afterwards published. It has often been reprinted as an original idea of the American philosopher; but, in reality, he never pretended to anything more than giving it its literary style, and the idea can be traced back through a devious channel to Saadi, the Persian poet, who, after all, relates it as coming from another person. It was as follows:  Printing Press worked on by Franklin while in London That Franklin should have ascended from the condition of a journeyman compositor to be a great philosopher and legislator, and 'to stand before kings,' is certainly one of the most interesting biographical facts which the eighteenth century presents. Without that frugal use of means, the want of which so signally keeps our toiling millions poor, it never could have been. Of ever memorable value is the anecdote he tells of his practice in a London printing-office. 'I drank only water,' says he; 'the other workmen, near fifty in number, were great drinkers of beer. On one occasion, I carried up and down stairs a large form of types in each hand, when others carried but one in both hands. They wondered to see that the Water American, as they called me, was stronger than themselves who drank strong beer. We had an alehouse boy, who always attended in the house to supply the workmen. My companion at the press drank every day a pint before breakfast, a pint at breakfast with his bread and cheese, a pint between breakfast and dinner, a pint at dinner, a pint in the afternoon about six o'clock, and another when he had done with his day's work. I thought it a detestable custom; but it was necessary, he sup-posed, to drink strong beer that he might be strong to labour. I endeavoured to convince him that the bodily strength afforded by beer could only be in proportion to the grain or flour of the barley dissolved in the water of which it was made; that there was more flour in a pennyworth of bread; and therefore, if he could eat that with a pint of water, it would give him more strength than a quart of beer. He drank on, however, and had four or five shillings to pay out of his wages every Saturday night for that vile liquor; an expense I was free from. And thus these poor devils kept themselves always under.' THE RETREAT FROM CAUBUL, 1842The British power went into Afghanistan, in 1839, upon an unrighteous cause. The punishment which Providence, in the natural course of events, brings upon such errors, overtook it towards the close of 1841, and on the 6th of January it became a necessity that an army of about 4,500 men, with 12,000 camp followers, should commence a precipitate retreat from its Caubul cantonments, through a difficult country, under frost and snow, which it was ill-fitted to endure, and harassed by hordes of implacable enemies. The Noche Triste of Cortez's troops on their retirement from Mexico, the terrible retreat of Napoleon's army from Moscow, even the fearful scenes which attended the destruction of Jerusalem, scarcely afford a more distressing narrative of human woe. The first day's march took them five miles through the snow, which was in many places dyed with their blood. They had to bivouack in it, without shelter, and with scarcely any food, and next morning they resumed their journey, or rather flight, -a long confused line of soldiery mixed with rabble, camels and other beasts of burden, and ladies with their children; while the native bands were continually attacking and plundering. The second evening saw them only ten miles advanced upon their fatal journey, and the night was again spent in the snow, which proved the winding-sheet of many before morning. It is believed that if they had started more promptly, and could have advanced more rapidly, the enemy, scarcely prepared to follow them, could not have proved so destructive. But the general - Elphinstone, - and other chief officers, were tempted to lose time in the hope of negotiating with the hostile chiefs, and particularly Akbar-Khan, for a purchased safety. Unfortunately, the native chiefs had little or no control over their followers. It was on this third day that they had to go through the celebrated Koord-Caubul Pass. The force, with its followers, in a long disorderly string, struggled on through the narrow defile, suffering under a constant and deadly fire from the fanatical Ghilzyes, or falling under their knives in close encounter. Thus, or by falling exhausted in the snow, 3,000 are said to have perished. Another night of exposure, hunger, and exhaustion followed. Next day, the sadly reduced files were stayed for a while, to try another negotiation for safety. The ladies and the married officers were taken under the protection of Akbar-Khan, and were thus saved. The remaining soldiery, and particularly the Indian troops, were now paralyzed with the effects of the cold, and scarcely able to handle or carry their arms. Many were butchered this day. They continued the march at night, in the hope of reaching Jugdulluck, and next day they still went on, doing their best to repel the enemy as they went. Reduced to a mere handful, they still exhibited the devoted courage of British soldiers. While the wretched remnant halted here, the general and two other officers gave themselves up to Akbar-Khan, as pledges that Jellalabad would be delivered up for the purchase of safety to the troops. The arrangement only served to save the lives of those three officers. The subsequent day's march was still harassed by the natives, and at a barrier which had been erected in the Jugdulluck Pass, the whole of the remainder were butchered, excepting about twenty officers and forty-five soldiers. After some further collisions with the foe, there came to be only six officers alive at a place about sixteen miles from Jellalabad. On the 13th of January, the garrison of that fortress saw a single man approaching their walls, mounted on a wretched little pony, and hanging exhausted upon its neck. He proved to be Dr. Bryden, the only one of the force which left Caubul a week before, who had escaped to tell the tale. It is easy to shew how the policy of particular commanders had a fatal effect in bringing about this frightful disaster to the British power-how, with better management on their part, the results might have been, to some extent, otherwise; but still the great fact remains, that a British army was where it ought never to have been, and of course exposed to dangers beyond those of fair warfare. An ancient Greek dramatist, in bringing such a tragedy before the attention of his audience, would have made the Chorus proclaim loudly the wrath of the gods. Ignorant men, of our own day, make comments not much different. The remark which a just philosophy makes on the subject is, that God has arranged that justice among men should have one set of effects, and injustice another. Where nations violate the Divine rule to do to others as they would have others to do to them, they lay themselves open to all the calamitous consequences which naturally flow from the act, just as surely as do individuals when they act in the same manner. TWELFTH-DAY This day, called Twelfth-Day, as being in that number after Christmas, and Epiphany from the Greek 'Ε∏ιΦáνєια', signifying appearance, is a festival of the Church, in commemoration of the Manifestation of Christ to the Gentiles; more expressly to the three Magi, or Wise Men of the East, who came, led by a star, to worship him immediately after his birth. (Matt. ii. 1-12.) The Epiphany appears to have been first 'observed as a separate feast in the year 813. Pope Julius I is, however, reputed to have taught the Church to distinguish the Feasts of the Nativity and Epiphany, so early as about the middle of the fourth century. The primitive Christians celebrated the Feast of the Nativity for twelve days, observing the first and last with great solemnity; and both of these days were denominated Epiphany, the first the greater Epiphany, from our Lord having on that day become Incarnate, or made his appearance in 'the flesh;' the latter, the lesser Epiphany, from the three-fold manifestation of His Godhead-the first, by the appearance of the blazing star which conducted Melchior, Jasper, and Balthuzar, the three Magi, or wise men, commonly styled the three Kings of Cologne, out of the East, to worship the Messiah, and to offer him presents of 'Gold, Frankincense, and Myrrh'-Melchior the Gold, in testimony of his royalty as the promised King of the Jews; Jasper the Frankincense, in token of his Divinity; and Balthuzar the Myrrh, in allusion to the sorrows which, in the humiliating condition of a man, our Redeemer vouchsafed to take upon him: the second, of the descent of the Holy Ghost in the form of a Dove, at the Baptism: and the third, of the first miracle of our Lord turning water into wine at the marriage in Cana. All of which three manifestations of the Divine nature happened on the same day, though not in the same year. 'To render due honour to the memory of the ancient Magi, who are supposed to have been kings, the monarch of this country himself, either personally or through his chamberlain, offers annually at the altar on this day, Gold, Frank-incense, and Myrrh; and the kings of Spain, where the Feast of Epiphany is likewise called the 'Feast of the Kings,' were accustomed to make the like offerings.' In the middle ages, the worship by the Magi was celebrated by a little drama, called the Feast of the Star.: 'Three priests, clothed as kings, with their servants carrying offerings, met from different directions before the altar. The middle one, who came from the east, pointed with his staff to a star. A dialogue then ensued; and, after kissing each other, they began to sing, 'Let us go and inquire;' after which the precentor began a responsory, 'Let the Magi come.' A procession then commenced; and as soon as it began to enter the nave, a crown, with a star resembling a cross, was lighted up, and pointed out to the Magi, with, 'Behold the Star in the East.' This being concluded, two priests standing at each side of the altar, answered meekly, 'We are those whom you seek;' and, drawing a curtain, shewed them a child, whom, falling down, they worshipped. Then the servants made the offerings of gold, frankincense, and myrrh, which were divided among the priests. The Magi, meanwhile, continued praying till they dropped asleep; when a boy, clothed in an alb, like an angel, addressed them with, 'All things which the prophets said are fulfilled.' The festival concluded with chanting services, &c. At Soissons, a rope was let down from the roof of the church, to which was annexed an iron circle having seven tapers, intended to represent Lucifer, or the morning star; but this was not confined to the Feast of the Star.' At Milan, in 1336, the Festival of the Three Kings was celebrated in a manner that brings forcibly before us the tendency of the middle ages to fix attention on the historical externals of Christianity. The affair was got up by the Preaching Friars. 'The three kings appeared, crowned, on three great horses richly habited, surrounded by pages, body guards, and an innumerable retinue. A golden star was exhibited in the sky, going before them. They proceeded to the pillars of St. Lawrence, where King Herod was represented with his scribes and wise men. The three kings ask Herod where Christ should be born, and his wise men, having consulted their books, answer, at Bethlehem. On which the three kings, with their golden crowns, having in their hands golden cups filled with frankincense, myrrh, and gold, the star going before, marched to the church of St. Eustorgius, with all their attendants, preceded by trumpets, horns, asses, baboons, and a great variety of animals. In the church, on one side of the high altar, there was a manger with an ox and ass, and in it the infant Christ in the arms of his mother. Here the three kings offer Him gifts. The concourse of the people, of knights, ladies, and ecclesiastics, was such as was never before beheld. In its character as a popular festival, Twelfth-Day stands only inferior to Christmas. The leading object held in view is to do honour to the three wise men, or, as they are more generally denominated, the three kings. It is a Christian custom, ancient past memory, and probably suggested by a pagan custom, to indulge in a pleasantry called the Election of Kings by Beans. In England, in later times, a large cake was formed, with a bean inserted, and this was called Twelfth-Cake. The family and friends being assembled, the cake was divided by lot, and who-ever got the piece containing the bean was accepted as king for the day, and called King of the Bean. The importance of this ceremony in France, where the mock sovereign is named Le Roi de la Fève, is indicated by the proverbial phrase for good luck, 'Il a trouvé la fève au gâteau,' He has found the bean in the cake. In Rome, they do not draw king and queen as in England, but indulge in a number of jocularities, very much. for the amusement of children. Fruit-stalls and confectioners' shops are dressed up with great gaiety. A ridiculous. figure, called Beffana, parades the streets, amidst a storm of popular wit and nonsense. The children, on going to bed, hang up a stocking, which the Beffana is found next morning to have filled with cakes and sweetmeats if they have been good, but with stones and dirt if they have been naughty. In England, it appears there was always a queen as well as a king on Twelfth-Night. A writer, speaking of the celebration in the south of England in 1774, says: 'After tea, a cake is produced, with two bowls containing the fortunate chances for the different sexes. The host fills up the tickets, and the whole company, except the king and queen, are to be ministers of state, maids of honour, or ladies of the bed-chamber. Often the host and hostess, more by design, than accident, become king and queen. According to Twelfth-Day law, each party is to support his character till midnight.' In the sixteenth century, it would appear that some peculiar ceremonies followed the election of the king and queen. Barnaby Goodge, in his paraphrase of the curious poem of Nagcorgus, The Popish Kingdom, 1570, states that the king, on being elected, was raised up with. great cries to the ceiling, where, with chalk, he inscribed crosses on the rafters to protect the house against evil spirits.  The sketch above is copied from an old French print, executed by J. Mariatte, representing Le Roi de la Fève (the King of the Bean) at the moment of his election, and preparing to drink to the company. In France, this act on his part was marked by a loud shout of 'Le Roi boit!' (The king drinks,) from the party assembled. A Twelfth-Day custom, connected with Paget's Bromley in Staffordshire, went out in the seventeenth century. A man came along the village with a mock horse fastened to him, with which he danced, at the same making a snapping noise with a bow and arrow. He was attended by half-a-dozen fellow-villagers, wearing mock deers' heads, and displaying the arms of the several chief landlords of the town. This party danced the Hays, and other country dances, to music, amidst the sympathy and applause of the multitude. There was also a huge pot of ale with cakes by general contribution of the village, out of the very surplus of which 'they not only repaired their church, but kept their poor too; which charges,' Troth Dr Plot, 'are not now, perhaps, so cheerfully borne.' On Twelfth-night, 1606, Ben Jonson's masque of Hymem was preformed before the Court; and in 1613, the gentleman of Gray's Inn were permitted by Lord Bacon to perform a Twelfth-Day masque at Whitehall. In the masque the character of Baby cake is attended by 'an usher bearing a great cake with a bean and a I1 with good will have spared unto your lordship, pease.' On Twelfth-Day, 1563, Mary Queen of Scots celebrated the French pastime of the King of the Bean at Holyrood, but with a queen instead of a king, as more appropriate, in consideration of herself being a female sovereign. The lot fell to the real queen's attendant, Mary Fleming, and the mistress good-naturedly arrayed the servant in her own robes and jewels, that she might duly sustain the mimic dignity in the festivities of the night. The English resident, Randolph, who was in love with Mary Beton, another of the queen's maids of honour, wrote in excited terms about this festival to the Earl of Leicester. 'Happy was it,' says he, 'unto this realm, that her reign endured no longer. Two such sights, in one state, in so good accord, I believe was never seen, as to behold two worthy queens possess, without envy, one kingdom, both upon a day. I leave the rest to your lordship to be judged of. My pen staggereth, my hand faileth, further to write.' The queen of the bean was that day in a gown of cloth of silver; her head, her neck, her shoulders, the rest of her whole body, so beset with stones, that more in our whole jewel-house were not to be found. . . The cheer was great. I never found myself so happy, nor so well treated, until that it came to the point that the old queen [Mary] herself, to show her mighty power, contrary unto the assurance granted me by the younger queen [Mary Fleming], drew me into the dance, which part of the play I could with good will have spared unto your lordship, as much fitter for the purpose.' Charles I had his masque on Twelfth-Day, and the Queen hers on the Shrovetide following, the expenses exceeding £2000; and on Twelfth-Night, 1633, the Queen feasted the King at Somerset House, and presented a pastoral, in which she took part. Down to the time of the Civil Wars, the feast was observed with great splendour, not only at Court, but at the Inns of Court, and the Universities (where it was an old custom to choose the king by the bean in a cake), as well as in private mansions and smaller households. Then, too, we read of the English nobility keeping Twelfth-Night otherwise than with cake and characters, by the diversion of blowing up pasteboard castles; letting claret flow like blood, out of a stag made of paste; the castle bombarded from a pasteboard ship, with cannon, in the midst of which the company pelted each other with egg-shells filled with rose-water; and large pies were made, filled with live frogs, which hopped and flew out, upon some curious person lifting up the lid. Twelfth-Night grew to be a Court festival, in which gaming was a costly feature. Evelyn tells us that on Twelfth-Night, 1662, according to custom, his Majesty [Charles II] opened the revels of that night by throwing the dice himself in the Privy Chamber, where was a table set on purpose, and lost his £100. [The year before he won £1500.] The ladies also played very deep. Evelyn came away when the Duke of Ormond had won about £1000, and left them still at passage, cards, &c., at other tables. The Rev. Henry Teonge, chaplain of one of Charles's ships-of-war, describes Twelfth-Night on board: 'Wee had a great kake made, in which was put a beane for the king, a pease for the queen, a cloave for the knave, &c. The kake was cut into several pieces in the great cabin, and all put into a napkin, out of which every one took his piece as out of a lottery; then each piece is broaken to see what was in it, which caused much laughter, and more to see us tumble one over the other in the cabin, by reason of the ruff weather.' The celebrated Lord Peterborough, then a youth, was one of the party on board this ship, as Lord Mordaunt. The Lord Mayor and Aldermen and the guilds of London used to go to St. Paul's on Twelfth-Day, to hear a sermon, which is mentioned as an old custom in the early part of Elizabeth's reign. A century ago, the king, preceded by heralds, pursuivants, and the Knights of the Garter, Thistle, and Bath, in the collars of their respective orders, went to the Royal Chapel at St. James's, and offered gold, myrrh, and frankincense, in imitation of the Eastern Magi offering to our Saviour. Since the illness of George III, the procession, and even the personal appearance of the monarch, have been discontinued. Two gentlemen from the Lord Chamberlain's office now appear instead, attended by a box ornamented at top with a spangled star, from which they take the gold, frankincense, and myrrh, and place them on an alms-dish held forth by the officiating priest. In the last century, Twelfth-Night Cards represented ministers, maids of honour, and other attendants of a court, and the characters were to be supported throughout the night. John Britton, in his Autobiography, tells us he ' suggested and wrote a series of Twelfth-Night Characters, to be printed on cards, placed in a bag, and drawn out at parties on the memorable and merry evening of that ancient festival. They were sold in small packets to pastrycooks, and led the way to a custom which annually grew to an extensive trade. For the second year, my pen-and-ink characters were accompanied by prints of the different personages by Cruikshank (father of the inimitable George), all of a comic or ludicrous kind.' Such characters are still printed. The celebration of Twelfth-Day with the costly and elegant Twelfth-cake has much declined within the last half-century. Formerly, in London, the confectioners' shops on this day were entirely filled with Twelfth-cakes, ranging in price from several guineas to a few shillings; the shops were tastefully illuminated, and decorated with artistic models, transparencies, &c. We remember to have seen a huge Twelfth-cake in the form of a fortress, with sentinels and flags; the cake being so large as to fill two ovens in baking.  One of the most celebrated and attractive displays was that of Birch, the confectioner, No. 15, Cornhill, probably the oldest shop of its class in the metropolis. This business was established in the reign of King George I, by a Mr. Horton, who was succeeded by Mr. Lucas Birch, who, in his turn, was succeeded by his son, Mr. Samuel Birch, born in 1757; he was many years a member of the Common Council, and was elected alderman of the ward of Candlewick. He was also colonel of the City Militia, and served as Lord Mayor in 1815, the year of the battle of Waterloo. In his mayoralty, he laid the first stone of the London Institution; and when Chantrey's marble statue of George III was inaugurated in the Council Chamber, Guildhall, the inscription was written by Lord Mayor Birch. He possessed considerable literary taste, and wrote poems and musical dramas, of which the Adopted Child remained a stock piece to our time. The alderman used annually to send, as a present, a Twelfth-cake to the Mansion House. The upper portion of the house in Cornhill has been rebuilt, but the ground-floor remains intact, a curious specimen of the decorated shop-front of the last century, and here are preserved two door-plates, inscribed, 'Birch, Successor to Mr. Horton,' which are 140 years old. Alderman Birch died in 1840, having been succeeded in the business in Cornhill in 1836 by the present proprietors, Ring and Brymer. Dr. Kitchiner extols the soups of Birch, and his skill has long been famed in civic banquets. We have a Twelfth-Night celebration recorded in theatrical history. Baddeley, the comedian (who had been cook to Foote), left, by will, money to provide cake and wine for the performers, in the green-room at Drury-lane Theatre, on Twelfth-Night; but the bequest is not now observed in this manner. THE CARNIVALThe period of Carnival-named as being carinvale, a farewell to flesh-is well known as a time of merry-making and pleasure, indulged in in Roman Catholic countries, in anticipation of the abstemious period of Lent: it begins at Epiphany, and ends on Ash Wednesday. Selden remarks: 'What the Church debars one day, she gives us leave to take out in another. First, we fast, then we feast; first, there is a Carnival, then a Lent.' In these long revels, we trace some of the licence of the Saturnalia of the Christian Romans, who could not forget their pagan festivals. Milan, Rome. and Naples were celebrated for their carnivals, but they were carried to their highest perfection at Venice. Bishop Hall, in his Triumphs of Rome, thus describes the Jovial Carnival of that city: 'Every man cries Sciolta, letting himself loose to the maddest of merriments, marching wildly up and down in all forms of disguises; each man striving to outgo others in strange pranks of humorous debauchedness, in which even those of the holy order are wont to be allowed their share; for, howsoever it was by some sullen authority forbidden to clerks and votaries of any kind to go masked and misguided in those seemingly abusive solemnities, yet more favourable construction hath offered to make them believe it was chiefly for their sakes, for the refreshment of their sadder and more restrained spirits, that this free and lawless festivity was taken up.' In modern Rome, the masquerading in the streets and all the out-of-door amusements are limited to eight days, during which the grotesque maskers pelt each other with sugar-plums and bouquets. These are poured from baskets from the balconies down upon the maskers in carriages and afoot; and they, in their turn, pelt the company at the windows: the confetti are made of chalk or flour, and a hundredweight is ammunition for a carriage-full of roisterers. The Races, however, are one of the most striking out-of-door scenes. The horses are without riders, but have spurs, sheets of tin, and all sorts of things hung about them to urge them onward; across the end of the Piazza del Popolo is stretched a rope, in a line with which the horses are brought up; in a second or two, the rope is ]et go, and away the horses fly at a fearful rate down the Corso, which is crowded with people, among whom the plunging and kicking of the steeds often produce serious damage. Meanwhile, there is the Church's Carnival, or the Carnivale Sanctificato. There are the regular spiritual exercises, or retreats, which the Jesuits and Passionists give in their respective houses for those who are able to leave their homes and shut themselves up in a monastery during the whole ten days; the Via Crucis is practiced in the Coliseum every afternoon of the Carnival, and this is followed by a sermon and benediction; and there are similar devotions in the churches. In the colleges are given plays, the scenery, drops, and acting being better than the average of public performances; and between the acts are played solos, duets, and overtures, by the students or their friends. The closing revel of the Carnival is the Moccoletti, when the sport consists in the crowd carrying lighted tapers, and trying to put out each other's taper with a handkerchief or towel, and shouting Sens moccolo. M. Dumas, in his Count of Monte Christo, thus vividly describes this strange scene: 'The anoccolo or moccoletti are candles, which vary in size from the paschal taper to the rushlight, and cause the actors of the great scene which terminates the Carnival two different subjects of anxiety: 1st, how to preserve their Moccoletti lighted; secondly, how to extinguish the moccoletti of others. The moccolo is kindled by approaching it to a light. But who can describe the thousand means of extinguishing the moccoletti? The gigantic bellows, the monstrous extinguishers, the superhuman fans? The night was rapidly approaching: and, already, at the shrill cry of Moccoletti! repeated by the shrill voices of a thousand vendors, two or three stars began to twinkle among the crowd. This was the signal. In about ten minutes, fifty thousand lights fluttered on every side, descending from the Palais de Venise to the Plaza del Popolo, and mounting from the Plaza del Popolo to the Palais de Venise. It seemed the fėte of Jack-o'-Lanterns. It is impossible to form any idea of it without having seen it. Suppose all the stars descended from the sky, and mingled in a wild dance on the surface of the earth; the whole accompanied by cries such as are never heard in any other part of the world. The facchino follows the prince, the transtavere the citizen: every one blowing, extinguishing, relighting. Had old Æolus appeared at that moment, he would have been proclaimed king of the Moccoli, and Aquilo the heir-presumptive to the throne. This flaming race continued for two hours: the Rue du Cour was light as day, and the features of the spectators on the third and fourth stories were plainly visible. Suddenly the bell sounded which gives the signal for the Carnival to close, and at the same instant all the Moccoletti were extinguished as if by enchantment. It seemed as though one immense blast of wind had extinguished them all. No sound was audible, save that of the carriages which conveyed the masks home; nothing was visible save a few lights that gleamed behind the windows. The Carnival was over.' In Paris. the Carnival is principally kept on the three days preceding Ash Wednesday; and upon the last day, the procession of the Bænf-gras or Government prize ox, passes through the streets; then all is quiet until the Thursday of Mid-Lent, or Mi-caréme, on which day only the revelry breaks out wilder then before. RHYTHMICAL PUNS ON NAMESOne of the best specimens of this kind of composition is the poem said to have been addressed by Shakespeare to the Warwiekshire beauty, Ann Hathaway, whom he afterwards married. Though his biographers assert that not a fragment of the Bard of Avon's poetry on this lady has been rescued from oblivion, yet, that Shakespeare had an early disposition to write such verses, may be reasonably concluded from a passage in Love's Labour Lost, in which he says: 'Never durst poet teach a pen to write, Until his ink were tempered with love's sighs.' The lines, whether written by Shakespeare or not, exhibit a clever play upon words, and are inscribed: To the idol of my eye, and delight of my heart, Ann Hathway Would ye be taught, ye feathered throng, With love's sweet notes to grace your song, To pierce the heart with thrilling lay, Listen to mine Ann Hathaway! She hath a way to sing so clear, Phoebus might wondering stop to hear. To melt the sad, make blithe the gay, And Nature charm, Ann hath a way; She hath a way, Ann Hathaway; To breathe delight, Ann hath a way. When Envy's breath and rancorous tooth Do soil and bite fair worth and truth, And merit to distress betray, To soothe the heart Ann hath a way. She bath a way to chase despair, To heal all grief, to cure all care, Turn foulest night to fairest day. Thou know'st, fond heart, Ann hath a way; She hath a way, Ann Hathaway; To make grief bliss, Ann hath a way. Talk not of gems, the orient list, The diamond, topaze, amethyst, The emerald mild, the ruby gay; Talk of my gem, Ann Hathaway! She hath a way, with her bright eye, Their various lustre to defy, The jewels she, and the foil they, So sweet to look Ann hath a way; She hath a way, Ann Hathaway; To shame bright gems, Ann hath a way. But were it to my fancy given To rate her charms, I'd call them heaven; For though a mortal made of clay, Angels must love Ann Hathaway; She bath a way so to control, To rapture the imprisoned soul, And sweetest heaven on earth display, That to be heaven Ann hath a way; She hath a way, Ann Hathaway; To be heaven's self, Ann hath a way! When James I visited the house of Sir Thomas Pope in Oxfordshire, the knight's infant daughter was presented to the king, with a piece of paper in her hands, bearing these lines: See! this little mistress here Did never sit in Peter's chair, Neither a triple crown did wear; And yet she is a Pope! No benefice she ever sold, Nor did dispense with sin for gold; She hardly is a fortnight old, And yet she is a Pope! No king her feet did ever kiss, Or had from her worse looks than this; Nor did she ever hope To saint one with a rope, And yet she is a Pope! 'A female Pope!' you'll say-' a second Joan!' No, sure-she is Pope Innocent, or none.' The following on a lady rejoicing in the name of Rain is not unworthy of a place here: Whilst shivering beaux at weather rail, Of frost, and snow, and wind, and hail, And heat, and cold, complain, My steadier mind is always bent On one sole object of content I ever wish for Rain! Hymen, thy votary's prayer attend, His anxious hope and suit befriend, Let him not ask in vain; His thirsty soul, his parched estate, His glowing breast commiserate In pity give his Rain! Another amorous rhymester thus writes: On a Young Lady Named Careless Careless by name, and Careless by nature; Careless of shape, and Careless of feature. Careless in dress, and Careless in air; Careless of riding, in coach or in chair. Careless of love, and Careless of hate; Careless if crooked, and Careless if straight. Careless at table, and Careless in bed; Careless if maiden, not Careless if wed. Careless at church, and Careless at play; Careless if company go, or they stay. E'en Careless at tea, not minding chit-chat; So Careless! she's Careless for this or for that. Careless of all love or wit can propose; She's Careless-so Careless, there's nobody knows. Oh! how I could love thee, thou dear Careless thing! (Oh, happy, thrice happy! I'd envy no king.) Were you Careful for once to return me my love, I'd care not how Careless to others you 'd prove. I then should be Careless how Careless you were; And the more Careless you, still the less I should care. Thomas Longfellow, landlord of the 'Golden Lion' inn at Brecon, must have pulled a rather long face, when he observed the following lines, written on the mantelshelf of his coffee-room: Toni Longfellow's name is most justly his due: Long his neck, long his bill, which is very long too; Long the time ere your horse to the stable is led, Long before he's rubbed. down, and much longer till fed; Long indeed may you sit in a comfortless room, Till from kitchen long dirty your dinner shall come: Long the often-told tale that your host will relate, Long his face while complaining how long people eat; Long may Longfellow long ere he see me again- Long 'twill be ere I long for Tom Longfellow's inn. Nor has the House of Lords, or even the Church, escaped the pens of irreverent rhyming punsters. When Dr. Goodenough preached before the Peers, a wag wrote: 'T'is well enough, that Goodenough Before the Lords should preach; For, sure enough, they're had enough He undertakes to teach. Again, when Archbishop Moore, dying, was succeeded by Dr Manners Sutton, the following lines were circulated: What say you? the Archbishop 's dead? A loss indeed!-Oh, on his head May Heaven its blessings pour! But if with such a heart and mind, In Manners we his equal find, Why should we wish for M-ore? Our next example is of a rather livelier description: At a tavern one night, Messrs More, Strange, and Wright Met to drink and their good thoughts exchange. Says More, 'Of us three, The whole will agree, There's only one knave, and that's Strange. 'Yes,' says Strange, rather sore, 'I'm sure there's one More, A most terrible knave, and a bite, Who cheated his mother, His sister, and brother. 'Oh yes,' replied More, 'that is Wright.' Wright again comes in very appropriately in these lines written On Meeting an Old Gentleman Named Wright What, Wright alive! I thought ere this That he was in the realms of bliss! Let us not say that Wright is wrong, Merely for holding out so long; But ah! 'tis clear, though we 're bereft Of many a friend that Wright has left, Amazing, too, in such a case, That Wright and left should thus change place! Not that I'd go such lengths as quite To think him left because he's Wright: But left he is, we plainly see, Or Wright, we know, he could not be: For when he treads death's fatal shore, We feel that Wright will be no more. He's, therefore, Wright while left; but, gone, Wright is not left: and so I've clone. When Sir Thomas More was Chancellor, it is said that, by his unremitting attention to the duties of his high office, all the litigation in the Court of Chancery was brought to a conclusion in his lifetime; giving rise to the following epigram: When More some years had Chancellor been, No more suits did remain. The same shall never more be seen, Till More be there again. More has always been a favourite name with the punsters-they have even followed it to the tomb, as is shown in the following epitaph in St. Benet's Churchyard, Paul's Wharf, London: Here lies one More, and no more than he. One More and no more! how can that be? Why, one More and no more may well lie here alone; But here lies one More, and that's more than one. Punning epitaphs, however, are not altogether rarities. The following was inscribed in Peter-borough Cathedral to the memory of Sir Richard Worme: Does worm eat Worme? Knight Worme this truth confirms; For here, with worms, lies Worme, a dish for worms. Does Worme eat worm? Sure Worme will this deny; For worms with Worme, a dish for Woruae don't lie. 'Tis so, and 'tis not so, for free from worms 'Tis certain Worme is blest without his worms. In the churchyard of Barro-upon-Soar, in Leicestershire, there is another punning epitaph on one Cave: Here, in this grave, there lies a Cave: We call a cave a grave. If cave be grave and grave be Cave, Then, reader, judge, I crave, Whether cloth Cave lie here in grave, Or grave here lie in Cave: If grave in Cave here buried lie, Then, grave, where is thy victory? Co, reader, and report, here lies a Cave, Who conquers death, and buries his own grave. |